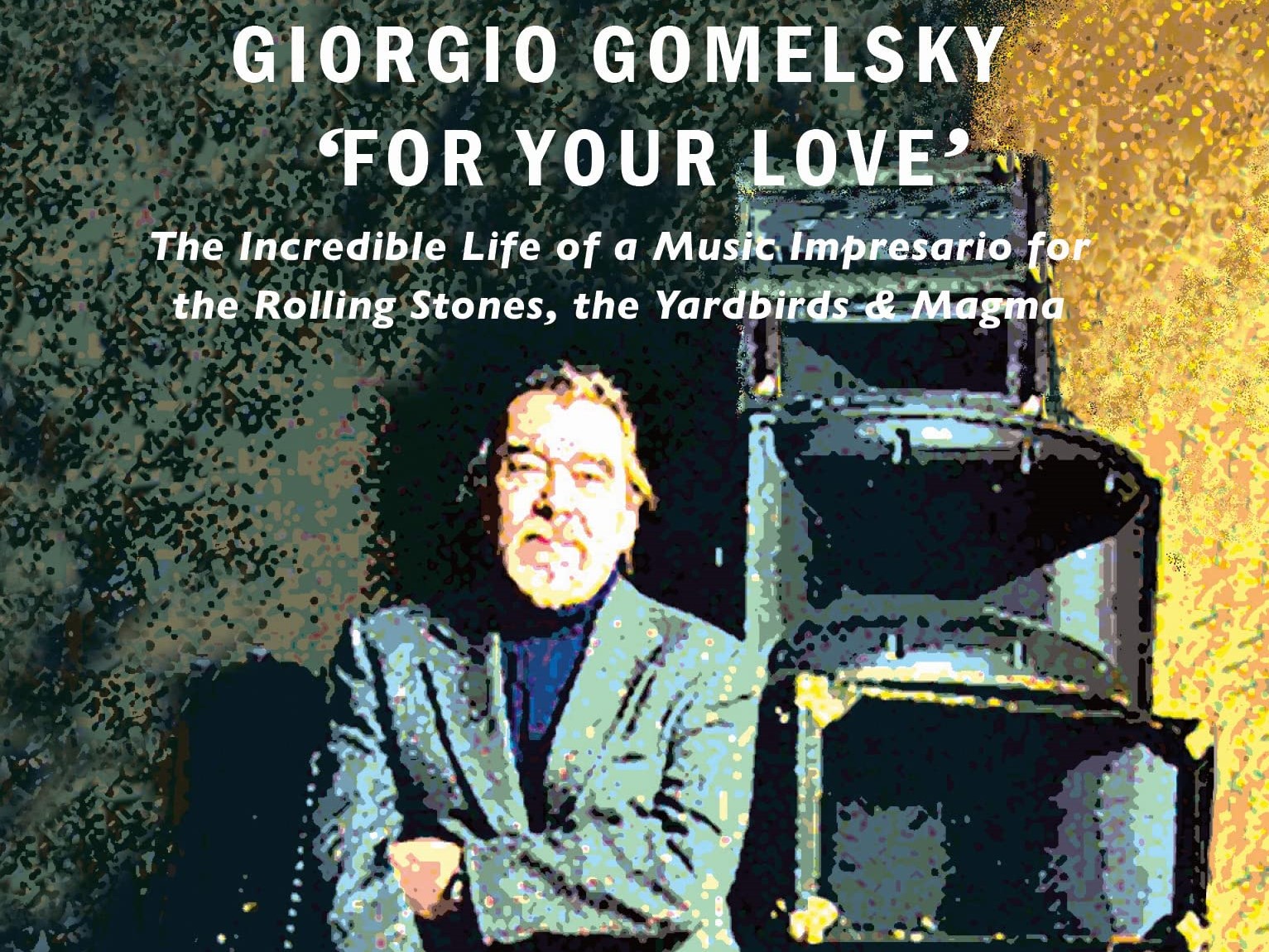

Jason Barnard speaks to Francis Dumaurier, author of the new book ‘For Your Love’: The Incredible Life of a Music Impresario for the Rolling Stones, the Yardbirds & Magma’. This groundbreaking biography sheds light on the influential figure of Giorgio Gomelsky, a visionary impresario and record producer who played a pivotal role in shaping the counterculture of 1960s London.

Gomelsky came to London in the 1950s and soon became a key figure in the burgeoning jazz and blues scene. He managed and produced some of the most important bands of the era and was known for his unconventional and forward-thinking approach.

Dumaurier, through his friendship with Giorgio and interviews with those who knew him, paints a vivid picture of Gomelsky’s life and legacy, exploring his complex relationships with the musicians he worked with, his impact on the music industry, and his lasting influence on the cultural landscape of the 1960s and beyond. In this interview, we will delve deeper into Gomelsky’s life and career.

What inspired you to write a biography of Giorgio Gomelsky – was it your friendship?

Shortly after I met Giorgio in January 1981, we spoke of the thesis I wrote in Paris on Jack Kerouac and the Beat Generation in June 1971, and Giorgio asked me if I would consider writing his biography back then. Even though I accepted right away, I quickly realized that doing this work would be near impossible as Giorgio was not focused enough to actually do what was required to sit down and write a serious book together. We mentioned it again several times over the years, but it never went anywhere. Other people also spoke to Giorgio about it, but nothing ever came from these conversations either. When Giorgio passed away, a senior editor at the Camion Blanc French publishing house asked me to write his biography in French that they would publish right away. As I wrote the book in French, I thought that it would be interesting to include recollections by people who knew Giorgio well for a long time; six of them did it right away, a couple of them later … but, since they were in English, I had to translate them in French so that they could be included in the French book. When the book was published in France, I sent a copy to these contributors who all said that they would appreciate an English translation since they did not speak or understand French. I hesitated because I had no publisher in sight here in the USA, but I finally agreed to do it. Once my translation from French into English was finished, I had a couple of American editors go through it to correct my use of the English language that was in dire need of improvement, and then I submitted the final draft to several American publishing houses. Two of them expressed interest but did not act on it as they considered the market to be too small for them to commit to a book release in the USA. Finally, one year ago, Cheryl Robson of Aurora Metro Books contacted me upon the recommandation of a mutual acquaintance, who was also a friend of Giorgio’s, and this is how this current form of the book came to be.

Can you tell us a bit about Giorgio Gomelsky’s childhood and upbringing, and how these experiences may have influenced his later career in the music industry?

Giorgio was born in the Soviet country of Georgia in 1934, and his father moved the family out of there when Stalinism became unbearable for them. They wanted to go to Switzerland through Italy, but it took a while before they were accepted and, in the meantime, they spent short periods of time in Egypt and Iran. This is where Giorgio got his first musical impressions from sounds and styles that were different, thanks to his father who was well versed in and open to all kinds of music from classical to experimental. They were finally accepted in Italy, from where they wanted to move to Switzerland where Giorgio’s father had studied medicine, but the fascists had closed the border and would not let them through. Italy is where Giorgio discovered jazz thanks to old 78s that were lying in an attic with an old gramophone. When the family finally could move to Switzerland, Giorgio took his love for jazz with him and, as a teenager, played drums in a trio, wrote articles for a jazz magazine, produced a jazz concert. At the age of 21, he raised money from an Italian television station to go film a documentary on jazz music in England, which he had heard was very popular. When he arrived in London, he discovered that the British trad jazz music and scene had nothing to do with the american jazz he loved, but he produced and directed anyway a documentary on Chris Barber that endeared him to Harold Pendleton of the International Jazz Federation that was headquartered in London, and befriended the musicians of the Blues Incorporated band that was playing weekly gigs at the Marquee with Charlie Watts on drums.

What was Giorgio Gomelsky’s role in helping to develop the blues scene and launch The Rolling Stones?

When Giorgio realized that the older members of Blues Inc. were not happy with the new rockier sound of the younger musicians, he decided to have his own weekly blues night at the Marquee with the blessing of Harold Pendleton. Giorgio produced the concert at the Marquee on July 12, 1962 where the Rollin’ Stones (as they spelled it back then) played their first concert ever with Brian Jones on guitar and blues harp, Ian Stewart on piano, Mick Jagger on vocals and blues harmonica, Dick Taylor on bass, Keith Richards on guitar, and the name of the drummer is still debatable. Brian and Stu were the founders of the band, but Brian was the leader. Brian was impressed with Mick, Keith and Dick, who were the Dartford boys unit, and the Dartford boys were impressed by Brian’s slide guitar. Brian was the only guitar player in England who could play slide guitar like Elmore James back then, and he even took the stage name of Elmo Lewis. Brian named the band Rollin’ Stone after a Muddy Waters blues. In the weeks following this historic concert, Giorgio decided to break away from Pendleton’s International Jazz Federation, and he rented a space near Piccadily Circus where he’d have his own weekly blues nights.

When Harold Pendleton got ticked off and accused Giorgio of stealing his ideas and musicians, Giorgio started to look around and, when he found out that there were successful musical events at Eel Pie Island, he started to investigate around Richmond where he booked the back room of the Station Hotel. Brian Jones was pestering Giorgio to play at his new place, but Giorgio did not remember them to be so great, and he booked instead the Dave Hunt Band (with an unknown Ray Davies on guitar) which had been recommended to him by Alexis Korner. Meanwhile, the Stones had auditioned Bill Wyman in early December 1962 who replaced Dick Taylor who wanted to play guitar instead of bass, and to start his own band with his pal Phil May; this band became the Pretty Things (named after the Bo Diddley song ‘Pretty Thing’ that Dick used to play with the Stones at his mother’s house). Finally, Charlie Watts, who was more of a jazz drummer, and who knew nothing about blues music then, finally agreed to join the Stones in early January 1963. After a couple of gigs at the Station Hotel, the Dave Hunt band got stuck in a snow storm and stood up Giorgio who got ticked off and fired them. He called Ian Stewart, who was the only member of the Stones that could be reached by phone as he had a job in a large company, and the Stones got the Sunday night residency at the Station Hotel where they played their first concert, as the lineup that would conquer the world, on February 24, 1963.

Do you think that Giorgio learnt from his experience with the Rolling Stones and how did his approach differ working with The Yardbirds?

Giorgio became the de facto manager of the Rollin’ Stones and helped them develop their style at his club. He also brought them to a recording studio to record a couple of songs for which he started to shoot a short black and white film, decades before music videos became a must for new bands on MTV. These audio recordings and film have disappeared. Anyway, Giorgio was helping the Stones with a verbal understanding that everything he did was for the best interest of the band, and that the band would continue using his services when things would improve thanks to his efforts. When Giorgio’s father passed away in Switzerland during the Spring of 1963, Giorgio went to the funeral service there, and took care of some family business. When he returned to London, he found out that Brian had signed a management contract with Andrew Loog Oldham behind Giorgio’s back while he was away. Giorgio felt betrayed and never forgave Brian Jones. When the Stones left their residency in the back room of the Station Hotel, which had been renamed Crawdaddy, Giorgio found the Yardbirds to replace them. But, this time, he wrote a contract with the band which would name him the manager as well as the producer of all their recordings that he would own. The musicians were guaranteed a weekly salary no matter how well the events would do. Lesson learned …

What was Giorgio Gomelsky’s management style like, and how was it different to other managers in the music industry at that time?

There are two distinct parts of management to consider here. One was the creation of events where the bands would develop their style. For the Stones, it was the extended versions of Bo Diddley songs that the band used to drive the crowds into a frenzy as Giorgio initially encouraged them to do so from the early days of the Station Hotel. For the Yardbirds, it was the Rave Up that would slow down the beat and the volume of a song at some point only to bring them back in full force in an orgasmic show of force. Both the Stones and the Yardbirds were encouraged by Giorgio to soar from the initial blues style to an obsessive manic beat that would drive their crowds crazy. The second part of management concerns the business side of it, and Giorgio had no true management background. He would do his best to move the moneys around to cover expenses, and nobody ever sued him for mismanagement or worse, but it is a known fact that some of the musicians were unhappy with the lack of income they saw in return for their efforts, specially those who did not write their own songs, and who had no income derived from copyrights. Giorgio found himself in a position where he would both manage the activities and finances of the band, and produce the recordings of their songs, activities that he learned as he went along. In comparison, the Beatles had Brian Epstein as a manager who already drove his own fairly succesful business before he met the band, and George Martin who was a staff producer for a large established recording company.

You highlight Giorgio’s key role in the development of The Yardbirds including ‘For Your Love’ and ‘Still I’m Sad’. Do you think this is underplayed now and what was it about him that made him so effective in shaping the band’s sound during this period?

Giorgio was extremely creative in the pursuit of new sounds. It was him who came up with the idea of the harpsichord for the intro of ‘For Your Love’, the sitar for ‘Heart Full of Soul’ (even if it is Jeff Beck who ends up playing the sound on guitar for the recording of the song), and the use of feedback for guitars on stage. It was also his Georgian cultural background that naturally came out from deep within himself when he started to hum some kind of a Georgian melody in a bathroom with the other guys joining in. This is how the song ‘Still I’m Sad’ was born in which he ends up singing the bass part in the recording of the song (as well as the triangle), or to sing the NO parts in ‘A Certain Girl’. Giorgio was always searching for new ideas and news sounds, and he would have lunches with engineers who came up with new sounds (sometimes by accident, sometimes voluntarily) to see which ones he could use for his bands. But Giorgio never insisted on getting the recognition for these innovations, and he did not get much credit for them. Now, his contributions are obviously underplayed as very few people have any interest in who played what 60 years ago.

Also, when he took the Yardbirds on a tour of the USA in the Fall of 1965, he insisted on taking the band to the Sun studio in Memphis, and the Chess Records studio in Chicago. He was curious to see first hand how the American producers (Sam Phillips in Memphis, and the Chess brothers in Chicago) managed to get the sound of the drums that the English technicians did not seem to be able to get so faithfully. Big hits came for the Yardbirds out of these two experiences and collaborations with local American producers: “The Train Kept a-rolling” and ‘Mister You’re a Better Man Than I’ in Memphis, and ‘Shapes of Things’ and ‘I’m A Man’ in Chicago.

His two most important musical productions for his Marmalade label were the single, ‘This Wheel’s on Fire’ by Brian Auger & The Trinity, and the album ‘Extrapolation’ by John McLaughlin. What was his role in the production of these works, and how did they showcase his skills as a producer and promoter of emerging talent in the music industry?

‘This Wheel’s On Fire’ was definitely a hands-on job by Giorgio who was pushing the use of new sounds in a new psychedelic era, specially with the use of the Mellotron that was such an innovation in those days. But for ‘Extrapolation’, I think Giorgio’s talent was to give John McLaughlin the space and time to play freely his distinctly innovative approach to the guitar, regardless of any commercial priority or concern. Giorgio also said that he had been nurturing John into getting back in good health after a difficult period, and that it had helped John feel secure in Giorgio’s trustworthy environment.

What were some of the key projects that Giorgio worked on in the 1970s and beyond, and how did he approach these projects?

From 1970 to 1978, Giorgio worked exclusively in France with Gong and Magma, managing and producing the recordings of both bands at one time or another. What Giorgio discovered in France was the network of youth centers that were sponsored by the government, and that had small spaces with a stage where bands could play in front of a couple of hundred people. The managers of these spaces did not know how to use them properly, and Giorgio made a full use of it, getting his own bands – as well as other bands from France or other European countries – to use these spaces at little to no cost. This allowed him to bypass the establish touring agencies, and to do as he pleased freely and independently, while making money for the bands that no longer depended on survival jobs to be able to play their music, and giving the audiences alternative bands, sounds, and music to appreciate at a low price of admission. This was truly revolutionary, until Magma started to become more succesful and to play in larger venues.

When Giorgio moved to New York and settled in the house at 140 West 24th Street in Manhattan, he opened the house for bands to rehearse and to play private concerts under his complete control. Then, he produced a large concert called the Zu New Music Manifestival on October 8, 1978, in which 70 European and American musicians played in turn for a total of 14 hours. This ended being a financial disaster, but it did not prevent Giorgio from taking the idea on the road, from New York to Los Angeles, that ended losing money as well. Giorgio continued producing the recordings of some of the musicians that were rehearsing in the house, but he became disheartened with the music business and turned his interest to the new technologies of personal computers and the internet. However, the house continued to be used by bands who produced their own events there, without Giorgio’s direct involvement in the production of their music or their events other than collecting rent money.

One thing he continued doing for a while were his Tonka Wonka Monday night events at Tramps where he would put together bands that played different styles of world music and/or blues and indie rock. But that was more for fun than for commercial ventures.

What are your key memories from knowing him from the early 80s onwards? Can you share any interesting or lesser-known anecdotes?

My memories are both as a user of the place where I would rent space from Giorgio for rehearsing my bands there, or for producing my own events, and as a close friend when we were both broke and hungry. I shared in the book moments of intimacy, like sitting on the terrace of my building on Central Park South with Central Park at our feet, sipping champagne, watching the ballet of airplanes in the northeast corner of the sky as they would land at or take off from La Guardia airport, and talking about everything and anything that would come to mind. We would also spend hours on the phone complaining about our girlfriends, when we were both single, as the ladies were quite much younger than us with different priorities or interests.

Otherwise, all of us who were present in the house at that time remember fondly the S&M Club (Paddles) that used the main floor on the street level to host their sado-masochist parties twice a week. They were good tenants, who paid rent on time and kept the place clean, but neither Giorgio nor us would partake in their activities that were exclusively reserved for their members and paying customers anyway. However, there were times when my band would have to rehearse upstairs while the S&M parties were going on downstairs, and we would cross paths with ladies wearing French maid uniforms, and nothing else to cover their bare backs, while they were chasing patrons to hit their behinds with paddles, and/or pull on their nipple clamps. Some of the instruments, that were too big to move in and out of the house from party to party, were left behind unattended (such as big crosses hanging on the walls, and on which patrons would hang themselves while being “serviced”, or huge phallic “machines” on the floor), and our friends who would come to our own private parties on alternate dates were left wondering if the house had become some kind of an art gallery of a non-descript nature.

One anecdote that did not make the book: one night, around 11pm, Giorgio called me to ask if I’d join him to go to a party that was happening between his house and my apartment in midtown on the West side. We met at the building, went to the apartment, and quickly realized that we did not know anybody there. So we explored the place and found the master bedroom with a keyboard, a bass guitar, and a couple of amplifiers by the side of the bed. I picked up the bass, Giorgio the keyboard, and we plugged them in. I started playing the riff of ‘Live With Me’ by the Stones, and Giorgio started banging on the keyboard. The sound attracted a group of young ladies who jumped on the bed and started dancing around. The owner of the place came in as well and, when he saw the mess that we had created without his permission, unplugged the amps, escorted us to the door, and asked us to never return. We did leave, but not without a couple of charming young ladies who insisted on coming with us to Giorgio’s house. Actually, it’s a pretty good memory to hold, and it puts a smile on my face whenever I think about it.

In your opinion, what was the most significant achievement of Giorgio’s career, and why? What do you hope readers will take away?

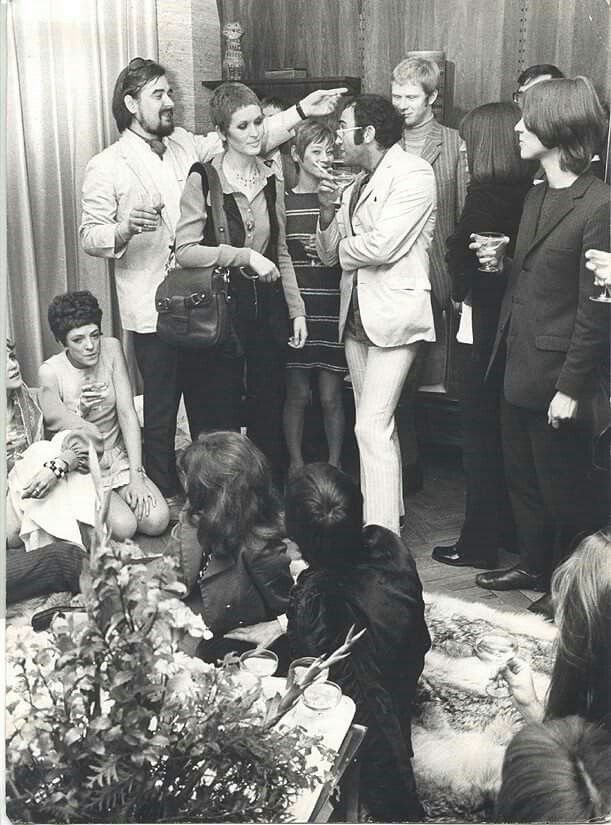

Giorgio was like a wizard (in the good sense of the term) who would bring all kinds of people, that would have never met otherwise, into one place where bands could play freely anything they wanted. When he liked the musicians, he would give them free advice and helped them find their groove. Giorgio stood behind the bar mixing drinks with all kinds of alcohol that he sold dirt cheap, and he let people do their own thing and enjoy the moment as they pleased. When the event was done with, he sat by the door on a high chair, rolled a cigarette, and – regardless of the fact that the event had turned out to be good or bad – he looked like a Buddha who was happy that he had created another vibe in the house. Actually, he called the house a “laboratory”, and he also believed that the house had its own spirit that he could not control. He was just the tenant and the vibe master.

Finally, I never ever met anyone who lived the words of John Lennon’s song “Imagine” to their fullest extent like Giorgio.

Further information

A tribute event to Giorgio Gomelsky will be held on 30 April 2023 at One Kew Road, Richmond: the former Crawdaddy Club founded by Gomelsky. The event celebrates the launch of the Francis Dumaurier book ‘For Your Love’: The Incredible Life of a Music Impresario for the Rolling Stones, the Yardbirds & Magma’. Tickets are available to purchase at Eventbrite

More information on the book and author Francis Dumaurier: Aurora Metro Books (imprint: Supernova Books)

Also on The Strange Brew, podcast interviews with Dick Taylor, Jim McCarty, Brian Auger, Jim Cregan, Steve Hillage

Worked with Giorgio once on a Beat Goes On show.

What a character!!!

He always jokingly (I think) told us that we, SURGERY should be playing in Minsk.