Canadian guitarist and former child actor Stan Endersby first came to prominence on the Toronto music scene during the 1960s with a succession of bands – The Just Us, The Tripp and Livingston’s Journey.

In the early 1970s, he recorded with future Motown star Rick James before heading to L.A at the end of the decade where he worked with former Love guitarist singer/songwriter Bryan MacLean. Later, he played alongside original members Bruce Palmer and Dewey Martin in Buffalo Springfield Revisited and also recorded with Toronto legends The Ugly Ducklings.

In October 2022, Endersby returned to England for the first time since leaving in the summer of 1970 to track down his old haunts and to reminisce about his time playing with former Kinks bass player Peter Quaife in the short-lived Maple Oak. He talks to Jason Barnard of the Strange Brew.

First of all, it’s amazing that you’ve got over to England after all these years.

I wanted to get over sooner, but I’m glad I made it. I’m having such an amazing time, going back more than 50 years.

You have roots in England because I understand your father originally came from over here. Is that right?

Yes. My father was a Bernardo’s child. At the age of nine he was sent to Canada. When he was 17, he lied about his age and joined the RAF and fought in the First World War.

During the Second World War, he commanded bases in Scotland and was then sent to Texas and taught American pilots how to fly.

Was your father a dancer and an actor?

Yes. While in Texas he met Irene and Vernon Castle, the Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers of that time. Vernon taught my father how to ballroom dance. At the end of the Second World War my father went back to London and became a professional ballroom dancer. He twice became the world’s ballroom champion.

After the war he moved to Toronto, Canada and had a weekly radio show on CBC called Shall We Dance.

He had five boys and all became actors. We did a lot of live television and theatre. My brother Ralph was in a series that was shown all over the world called The Forest Rangers. And Clive acted in the British production of Bye Bye Birdie with Marty Wilde and Chita Rivera. Brother Eric was in Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita.

In a way, you’ve got that artistic angle because you ventured into music.

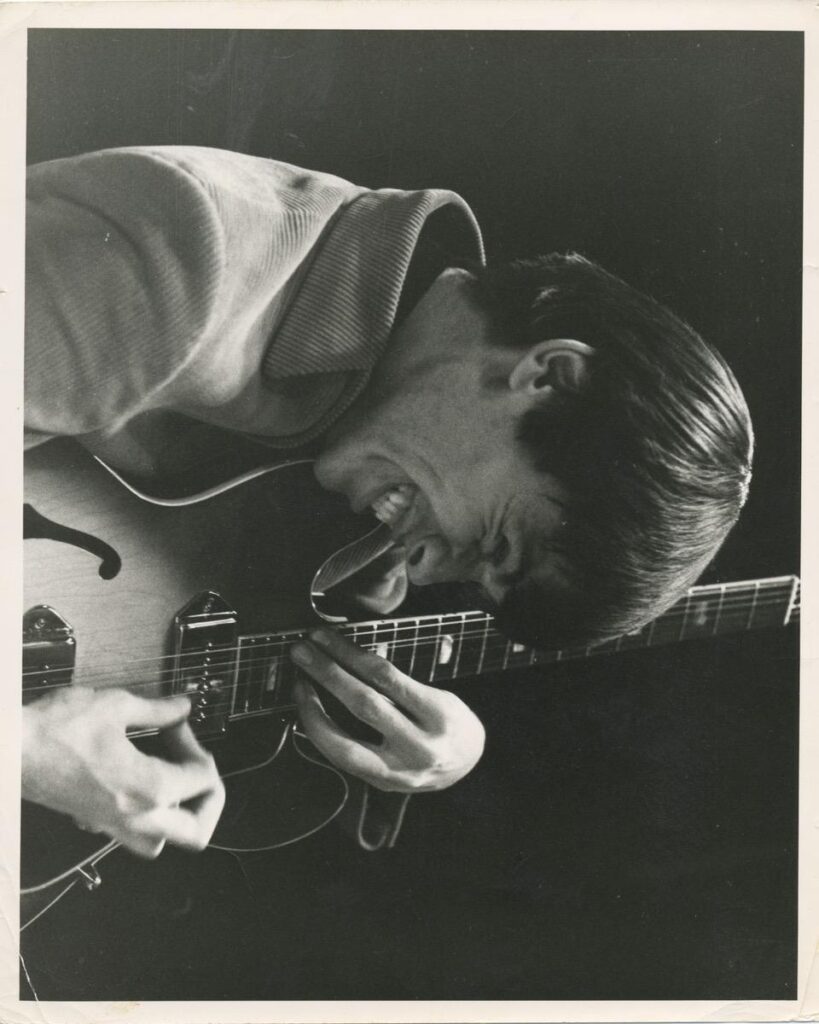

My father played guitar and sang and wrote songs. I had a little guitar tuned to an open tuning. I was crazy for Elvis and when I saw him live in 1957 it changed my life.

At the ‘Mayfair Garden Fete’ the band asked if anybody wanted to sing a song. My friends got me onstage and I sang “Blue Swede Shoes”. One of the guys in the band said, “Hey, if you got a guitar and learned a few chords, you could join a band.” That’s exactly what I did!

You were in a range of bands around the Toronto scene. But one of the bands that people will have some familiarity with, at least to some extent, was The Just Us.

Before I joined The Just Us I played a lot of bar gigs. You had to be 21 and we were 16 and if the morality cops came we would stop playing and sit in the boss’ Cadillac in the parking lot.

I played with CJ Feeney and The Spellbinders. Wayne Davis and I left to join The Just Us.

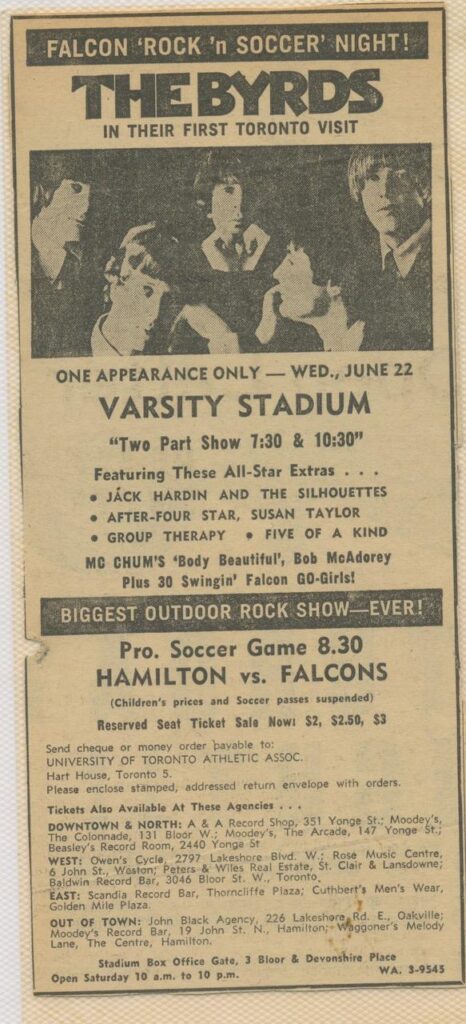

They were already on Quality Records. However, the producer went back to the States and gave our name to another band that came out with “Can’t Grow Peaches on a Cherry Tree”.

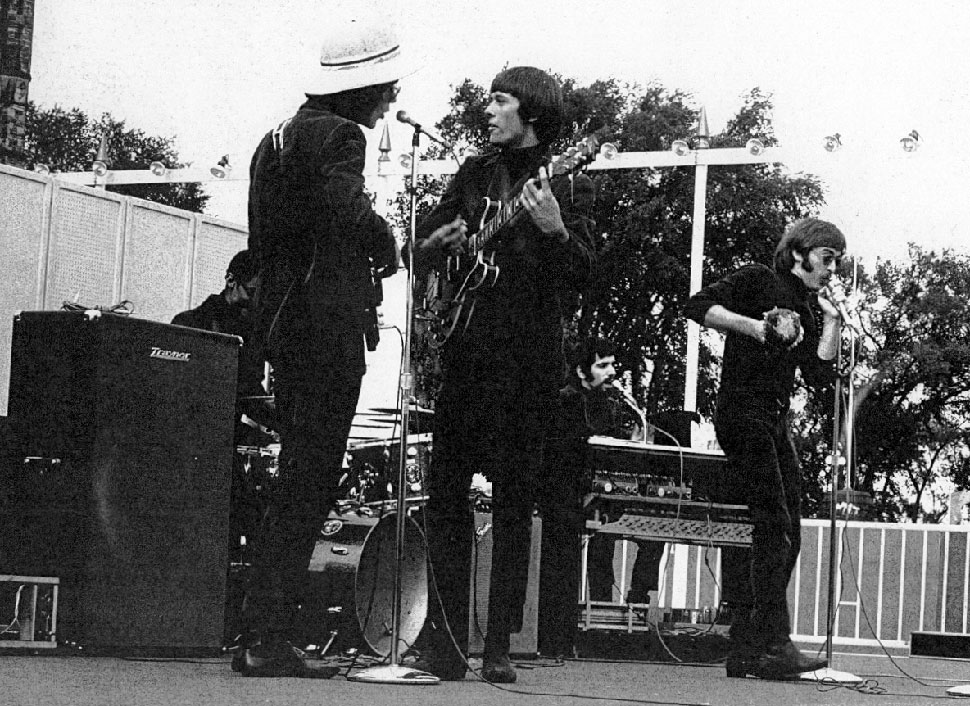

Being an R&B band we grew tired of people requesting this song so we had to change our name to ‘Group Therapy’ before we opened for The Byrds at Varsity Stadium in June 1966. We got on stage and some non-union band had a father who was a lawyer and they served us with some papers and we couldn’t use that name either. So we ended up becoming The Tripp.

Our singer was Jim Livingston who used to sing with Rick James in The Mynah Birds before Neil Young joined.

There were so many great musicians on that Toronto music scene around that time.

That’s right and they were just getting known. Like David Clayton-Thomas who later joined Blood, Sweat and Tears. The Sparrows became Steppenwolf. The Hawks became The Band and Neil Young and Bruce Palmer from The Mynah Birds formed Buffalo Springfield after driving to L.A. Musicians went down to the States to play.

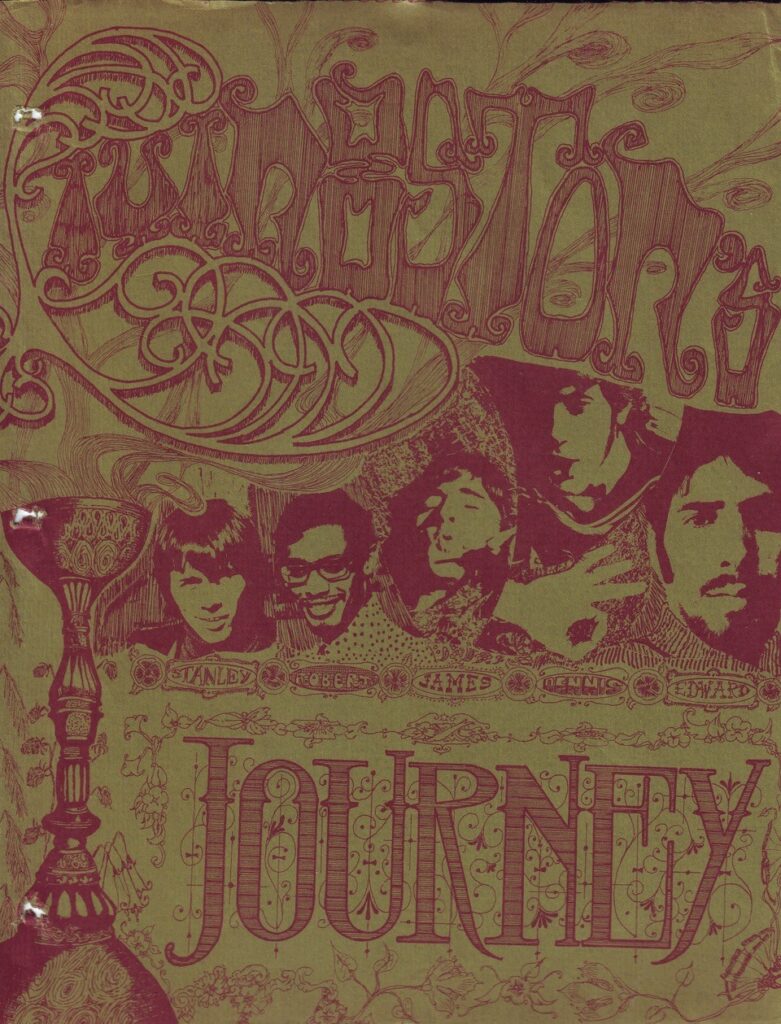

You had a change of name and sound, so The Just Us became The Tripp and ultimately Livingston’s Journey.

Correct. In The Tripp we had founding member Ed Michael Roth on the Hammond, and added Richard Bell on piano. Richard went on to play with Ronnie Hawkins, later joined Janis Joplin and The Full Tilt Boogie Band, and then The Band in 1991. In Livingston’s Journey we had a few changes in personnel. We got Dennis Pendrith on bass; he’s played with lots of people [like Bruce Cockburn] and is one of Canada’s top session players.

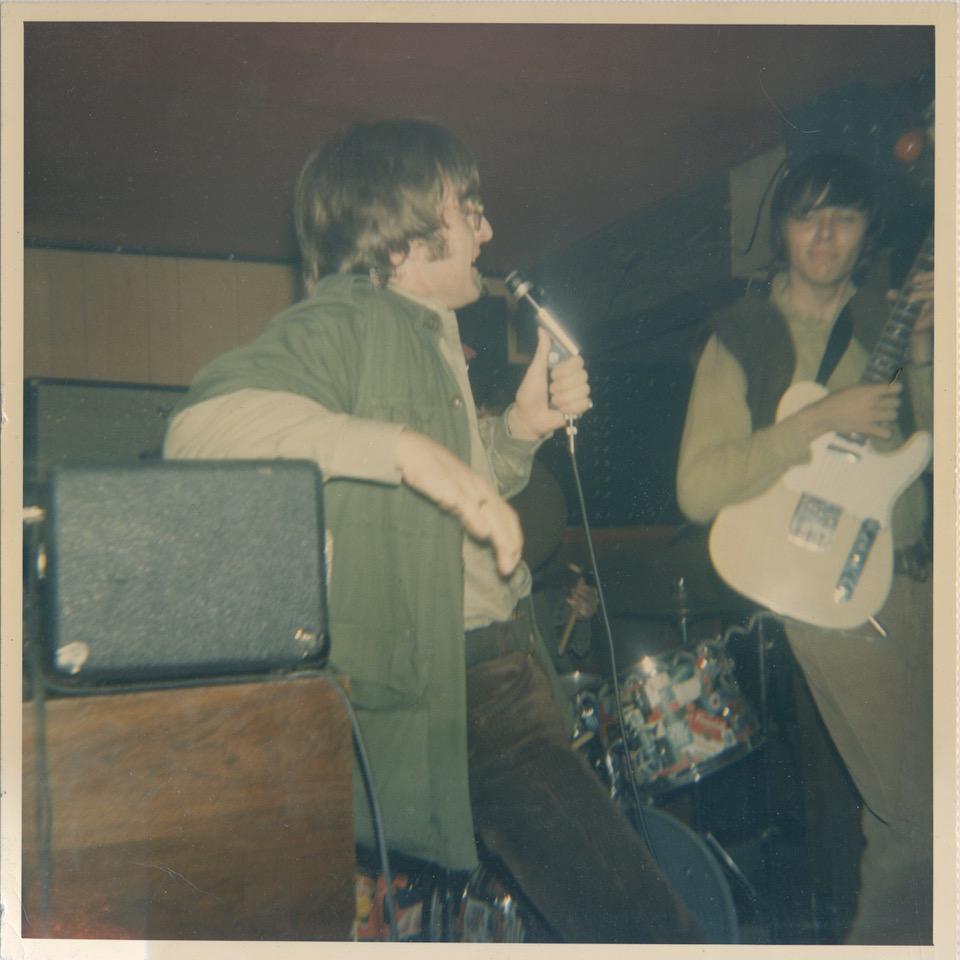

There was a live recording made of Livingston’s Journey at the Night Owl in Toronto.

Yeah, it was our last night before the band split up in spring of 1968. My brother Ralph taped the show with a Robert’s cross-field head tape recorder. I wanted to take it to London and play it for Apple Records. That was my plan.

So, this was late summer 1968?

Correct. Many of my Toronto musician friends were going down to the States, but there was a war on and I didn’t think it was a fun place to go. With my English roots and a brother living in London, I thought I’d check out the scene over there and see how I liked it.

You arrive in London and you met Peter Quaife on your first evening!

Well, it was sort of strange because I’d been in London six hours and I said to my brother Clive, “I’m going to check out the music scene”. He replied, “Stan, it’s late, everything closes early in London.”

Anyway, I found myself in Piccadilly Circus. I started hearing this music and I walked towards it and this guy at the door says, “Where are you from in the States?” I said, “I’m not from the States; I am from Canada”. He goes, “I’m sorry. My name’s Hugh O’Donnell and I own this club, Hatchetts Playground. He took me into the club, put me in this VIP section and brought me a rum and coke. I asked “Does anybody ever sit in with the house band?” He says, “You want to sit in?” and then shouted, “Let this guy sit in”.

There was this R&B singer called Horace Faith and he started doing this song and I started playing. The song finished and this guy comes up to me and he says, “You played in The Tripp in Toronto, didn’t you?” I said, “How did you know that?” He said, “My name is Lorne Michaels and I worked on the The Sunday Show you did for CBC TV. He asked me what I was doing in England and when I told him he said, “You’ll have no problem getting into a band”.

Two seconds later, this guy comes up and says, “Hi, my name is Bill Fowler and I was with the Arthur Howes Agency when we booked the Helen Shapiro tour for The Beatles. Peter Quaife from The Kinks would like to talk to you.” The Kinks were really loved in Canada. Weird….Six hours in London!

Peter said he was leaving The Kinks and he wanted me to be part of his new band. The next day I went to his flat in Muswell Hill and we talked. I said, “I’m going to go back to Canada to do a few things and if you ever do it, give me a call. It’s a big decision for you”.

I called Bill Fowler as I had this cross-field tape of Livingston’s Journey and I wanted to play it at Apple. He said, “I can arrange a machine that you can play it on at Chapel Music and how does Tuesday sound for visiting Apple?”

I went down to Apple and set up the tape in this room and I put it to this Beatles’ cover we used to do, “You Can’t Do That”. We had this version with augmented ninths; it was very different. I played it to a couple of people and they said, “Stop, rewind it” and left. When they came back I recognised Peter Asher.

You Can’t Do That by Livingston’s Journey at the Night Owl in Toronto in spring 1968; their final gig:

I played it for them and they said, “What are you doing here?” I said, “I thought I’d check out the scene and I had one serious offer already”. They asked me who it was and I said, “I can’t say. He hasn’t left his band and I’m not going to cause any problems [for him]”.

Now, I ended up getting a lot of work at Hatchetts. I backed up a lot of people in the house band [with drummer Lloyd Courtenay and bass player Brian Gill] and with Horace Faith. I also looked in the back of Melody Maker and responded to adverts like “Wanted guitar player”. I found it very interesting. You would phone the number and talk with a guy in the band. If you sounded ok you would meet them in a restaurant and talk some more and then they would take you to their rehearsal space.

On one occasion I went down to this rehearsal hall and played with these guys, which was a lot of fun. They said, “There’s this guy you got to meet. He’s living down the street and really doing well.” It was Peter Frampton. We’re sitting talking and he likes my Gibson 335 guitar. He was a super nice guy. (I think he was in The Herd then.)

Then, around Christmas ’68, I had to go back to Toronto and do a TV show for Jim Henson called The Cube. Today it has a real cult following.

It was filmed in Canada for NBC. I met Jerry Jules and Frank Oz. Jim Henson wrote the show. It was such a great thing to do. It was what you would call “experimental television”. It was all about this guy who was locked in this cube. He couldn’t get out and all of these different people walked in. There’s a scene with musicians and that’s me, [keyboard player] Marty Fisher, [drummer] Gordon MacBain and my brother Ralph. Marty and Gordon had recently finished playing with Bruce Cockburn. The Cube was very ahead of its time.

So, you were only back in Toronto a few months before you got the call from Peter to form what became Maple Oak.

The house band at the Rock Pile (John Brower’s Club) was called Transfusion. Guitarist Danny McBride left (later to play with Chris DeBurgh), so I was asked to be part of this new band to open for Frank Zappa. The gig was great; we started with an instrumental that we wrote. I pulled out all my Steve Cropper grooves and licks. Pat Little was on drums, Andy Kaye on guitar, Louie Yacknin on bass, Ray Arkenstaul on Hammond and Simon Caine, the front man. A wonderful night.

We were offered a gig at a new club as the house band that was opening called the Electric Circus. We auditioned and got the gig. They all knew that if I got the call from Peter I was gone and that was what happened. I got the call.

I took keyboard player Marty Fisher to England with me.

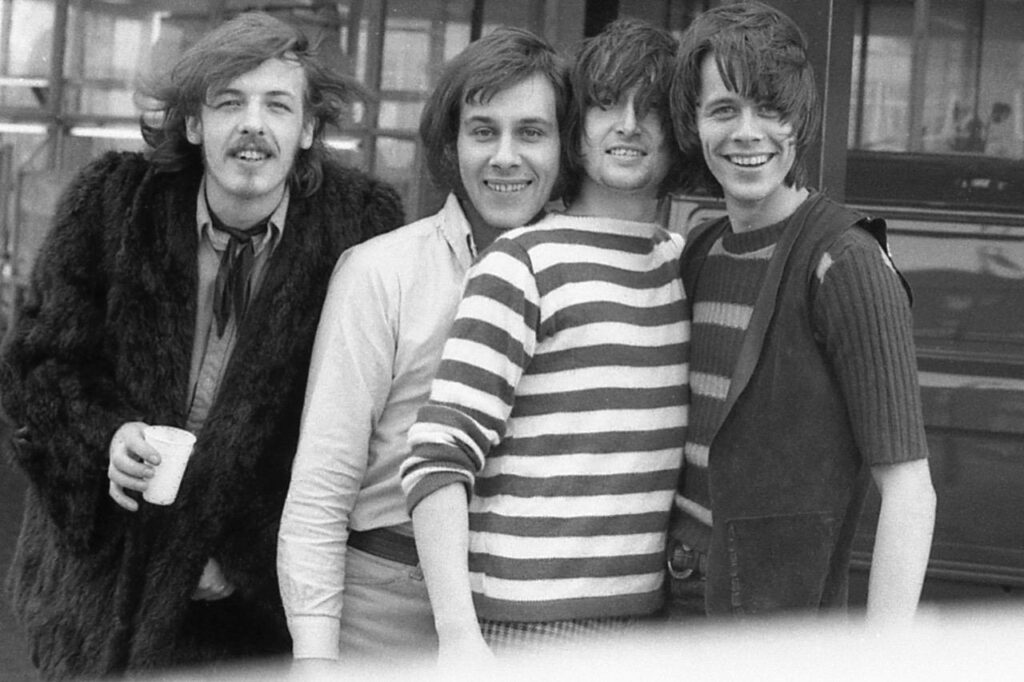

Peter brought Mick Cook so was Maple Oak half English and half Canadian?

Yes. I would have bought my friends from Livingston’s Journey. I would have bought keyboard player Ed Roth, but he was already in Los Angeles playing with Neil Merryweather and then Rick James.

Mick Cook was a really great guy. It just didn’t work out [and Gordon MacBain replaced him in June].

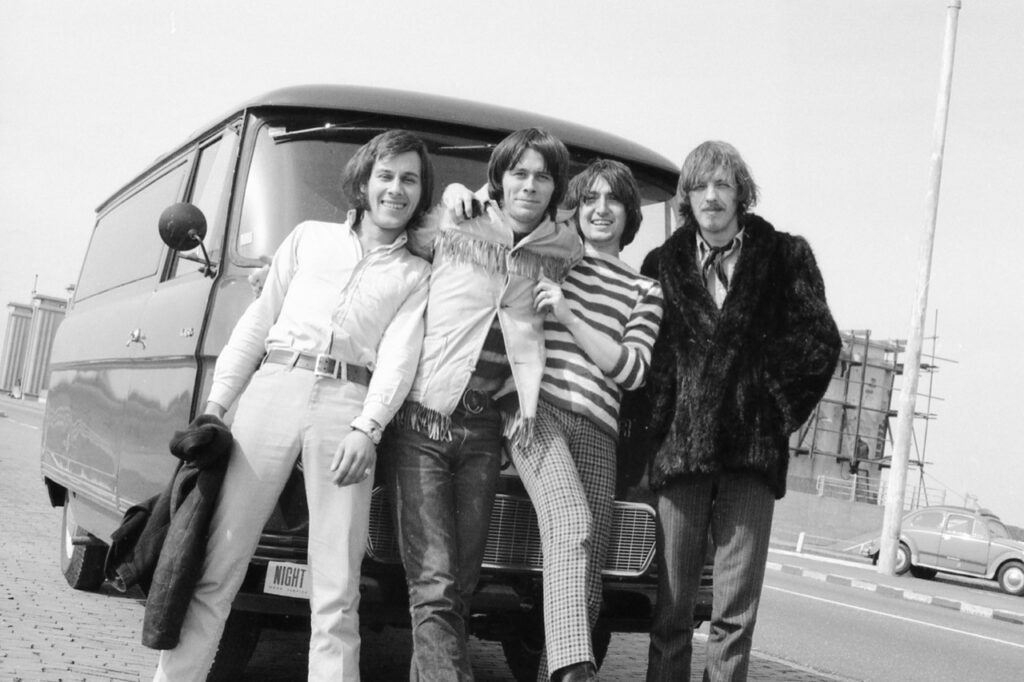

With Pete’s connections in Denmark, Maple Oak did a tour over there?

Correct. We got to play a place called Le Carousel in Tivoli Gardens all through May and June 1969. Peter did have relatives over there; his Danish wife and her family.

We had a great time hanging and jamming with the Danish bands. We worked hard to get our show together.

I saw that Steppenwolf was playing in Copenhagen. John Kay wanted to meet Peter, so we went over to his hotel. We then met up with them at a club after their show. It was great to see all of them.

I can’t remember who told me this, but when they first started going to Europe people would ask them, “Which one of you is Steven Wolf?” I must have found this very funny to remember that all these years.

Back in England, Peter phoned me to say, “There’s this American guy and he’s playing the Marquee (15 June 1969). Get your driver, and he will take you there.” We went down to the Marquee and it’s James Taylor; I think before his Apple LP was out. We couldn’t believe the songs and his guitar playing was incredible. The audience was making a hell of a racket and then within one or two minutes of him playing you couldn’t hear a peep in the room.

Then, we all went to Stonehenge and hung out till we got kicked out at four in the morning and drove James Taylor back to where he was staying and he played us a few tunes. Great times!

Copenhagen sounded like a great grounding. When you came back, Mick Cook left and you got Gordon MacBain over from Toronto.

Yeah, I had hired both Gordon MacBain and Marty Fisher to do The Cube, [so they were an obvious choice]. They had both played with a horn band called Bobby Kris & The Imperials earlier in the 1960s (Ed. Bobby Kris fronted the final Livingston’s Journey line up and sings on the live tape mentioned earlier). Then they went to play with Bruce Cockburn in The Flying Circus and Olivus.

You played quite a few places in England, didn’t you?

Yes, we did. We played the Marquee with Renaissance [in late 1969]. We also played the Speakeasy and some universities and St Donat’s Castle in Wales that was a boarding school. A student from the school asked us to play the instrumental Transfusion had done when we opened for Frank Zappa. He must have been from Toronto.

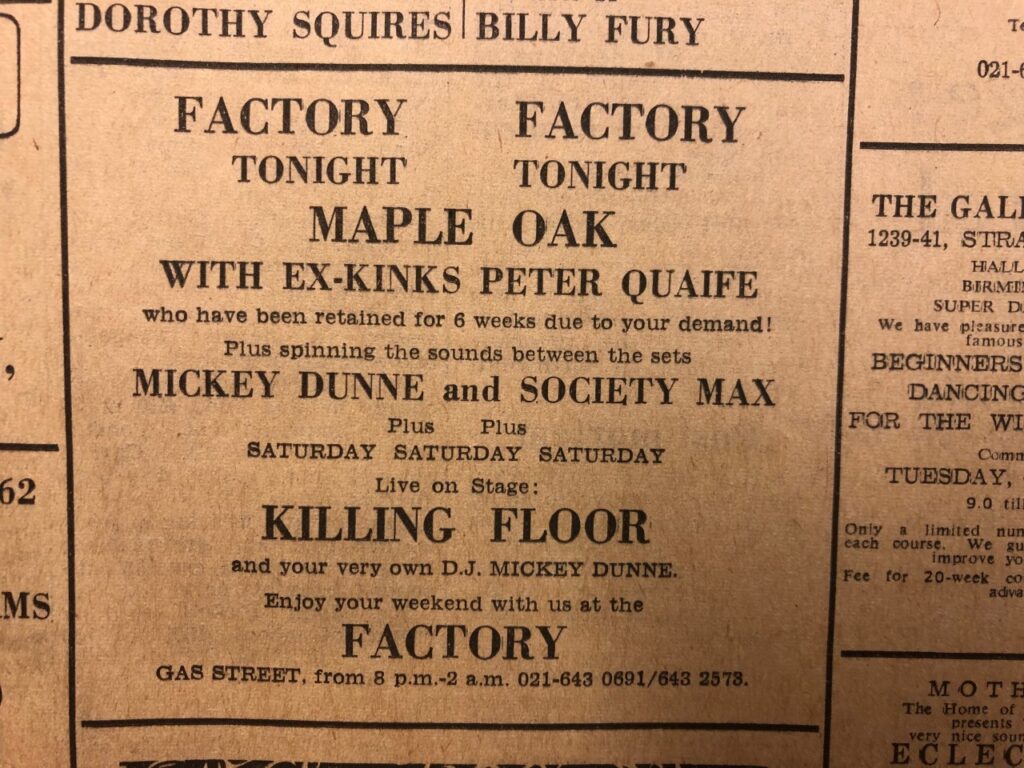

There was a club in Birmingham called the Factory and they really understood us. They would sit down and really listen to us.

We were doing some Tim Hardin and some Bruce Cockburn tunes. (Ed. Maple Oak were residents in the Factory in Birmingham in October-November 1969 and played many Fridays.)

We played the Roundhouse in Chalk Farm a lot because we lived close by in Belsize Park. One gig we did was with Curved Air and Ginger Johnson. We met the South African band with leader Ginger Johnson. They were wonderful and played so great. I’m pretty sure they played on the song “Sympathy of the Devil.”

We also played in Belgium, Amsterdam, and West Germany.

You got quite a lot of interest from labels.

Well because of Peter there was a lot of interest. We had three record companies that wanted us.

Decca was one and we had some serious talks with them. Later while we were in Decca’s offices Marty stands up and says, “Why should we sign with you? You turned down The Beatles”. And they got really pissed off. They said, “Follow us”. We went down the hall and they put us in a room and they played the Beatles’ audition tape. We loved it. I guess Marty did that because he wanted to hear it, right? Then Peter said, “We don’t need an advance”. We said, “Peter, quit joking.” (He wasn’t.) We said we would go to this restaurant to discuss what we needed and be right back. We agreed that we needed the advance to buy equipment, the van and that sort of stuff, so we signed with Decca.

Muff Winwood from Island was interested and that might have been a better home but because of the advance, you went with Decca?

Muff Winwood of Island Records really liked our band and would have given us all the studio time we needed and we would have gotten some direction there. But we were young, foolish kids. Muff Winwood really saw potential and we liked him instantly. But they couldn’t give us any money and we needed to function as a band. We also had an offer from Liberty Records.

Pete came from The Kinks. What did he tell you in relation to what wasn’t working for him and why he wanted to do more of his own thing with you?

I could never figure out the relationship with Peter and Maple Oak’s manager Derek Cooper. Cooper wasn’t doing the whole “You’re the star Peter you’ve got to do your own thing”. It wasn’t like that. Peter was too smart to fall for something like that. I don’t really know what his reason for leaving The Kinks was. He just wanted a change and was set on leaving. He loved the guys in The Kinks and he never said one negative word about anybody in that band. Yes, he did tell me things, but that’s Kinks business and it’s so long ago now I can’t remember half of it anyway.

What was his and your relationship with the remaining members of The Kinks during that period?

We didn’t see them. The first time I was over in 1968 Peter took me to a pub and I was introduced to Ray and had a couple of drinks. It was very cordial. I went to the Kinks office and Peter showed me around. He had a baby girl.

I remember Peter took me down to Top of the Pops and Canadian band The Guess Who were on.

Derek Cooper was our only manager. Peter had decided on him and, not to put anything on Peter, in those days there weren’t a lot of great managers that knew the record business.

You had the Decca deal and in spring 1970 you went into the studio to record a single.

That was a bit of a nightmare. We had this TV host from Ready Steady Go and he was going to produce us. We said, “Okay, if you are producing us, we are playing here and here. Come and hear the band you are producing”. He never came.

We really tried working with these people but we couldn’t. Later on, when we were recording a Bruce Cockburn tune, he said, “I don’t like those two lines; you have to change those lines.” We went, “Whoa, wait a minute. We aren’t going to change the lines to another songwriter’s song.”

Luckily, we had Mike Hutson, a person we met at United Artists, who decided we should have our publishing with United Artists. They had them put a clause in our contract that if we didn’t like how the Decca thing went we could go to another studio and send them the bill. So we went to De Lane Lea in Dean Street.

The thing that really got me was that when we went to the first Decca studio in West Hampstead we walked in and all the Ampex machines were standing in the hallway. We walk into the room and there’s a digital board and all these engineers going, “Where is everything?” It was freaking them out.

In April 1970, Maple Oak’s single, MacBain’s “Son of a Gun” with your own song “Hurt Me So Much” on the flipside was released. What was the rationale behind choosing “Son of a Gun”?

The song had a nice groove. We were happy with it. We did it with [former Hedgehoppers Anonymous] guitarist John Stewart producing. He was great to work with.

Did you feel you got the support from Decca you wanted with the release of the single?

We were getting ready to play the London Palladium with Roger Whittaker and Matt Monroe and we were rehearsing at Decca’s office. The head of the company came down and said, open with “Guitar Pickers” when you play the London Palladium.

I thought Decca was okay but we needed direction and didn’t get it. Whether we were in tune enough to take direction, I don’t know. We were young kids that thought we knew everything. I can’t blame it on one party but we really needed someone that understood what was going on in a music business sense.

The single didn’t chart so how long did it take Peter to start to become disillusioned with the way things were going?

It was a lot of different things. He wanted to go to the pub and talk and the guys wanted to rehearse and that was upsetting. They were unhappy with his style of playing. He played really strong on the single. He got that heavy British bass sound a lot of British players were getting.

But we were trying to do something different musically at the time. Country rock was in its infancy in the USA and Britain. This difference led to Peter leaving the band.

I remained friends with Peter my whole life. I used to see him in Canada (Ed. Peter Quaife lived in Belleville, Ontario from 1980 until 2005 when he moved to Denmark.)

I was working mostly in L.A. and touring during that time, so I wasn’t in Toronto that much. When I got home there was always a message from Peter to get in touch. We were always good friends, but he had just had enough of the whole music scene.

Are there any other recordings with Peter?

We all did the BBC audition tape that everybody has to do. I have that. We did a show with Credence Clearwater around April 1970 for BBC but I can’t find out what the show was called.

You recorded the LP as a trio and I presume it was still in the can when you went back to Canada and released after you’d left?

We went back to Canada in August 1970 and played a few gigs as Maple Oak and then said, “No more, time to move on.” Then the album came out. I went down to Decca in Montreal and they heard “Guitar Pickers” and said they could edit it and release it as a single. I said, “No, just let it be”.

There were a lot of things going on. It had been a tough LP to do in some ways. We were all really burned out.

What are your reflections on the LP? It’s available digitally now.

I don’t know if the mastering was good. Marty played a left-hand bass on the keyboards. Stevie Wonder was doing something similar around then. Marty was a great Hammond player but didn’t want to play it and Gordie got him to play it on one song! We were happy with John Stewart’s engineering and I later got him a studio job in Toronto (see part 2).

Some people love some of it. There are people who love “Son of a Gun” and say “I’ve been looking for this for years”. Everyone has got their opinion.

It’s a very hard question to ask me. We were ahead of our time with the country rock. The record market wasn’t great for the music we were doing. I just noticed on the net they call it Cosmic Country. They had Maple Oak as pre-Cosmic Country. There were not many people doing what we were doing.

Before the album was released Decca sent me a telegram asking who wrote which songs. So, I sent a telegram with the information that was needed. They also said they would pay my way to London and I could put on a real bass and clean up some tracks. I appreciated that a lot. But it would have been a band decision and as the band no longer existed I let it go.

I was coming from being R&B guitar player and all of a sudden now I am singer/songwriter, so when I went back to Canada, I moved to the country and worked on my singing and songwriting. I played at places like the Riverboat in Toronto and folk gigs. I also backed up other artists on lead guitar and did sessions. In 1971, I worked with Rick James.

To be continued…

Acknowledgements

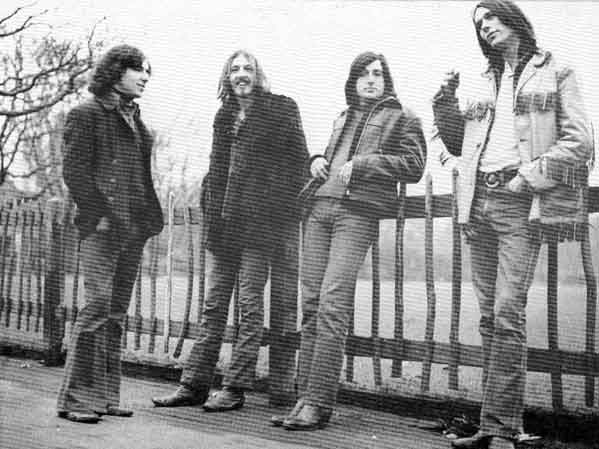

Thanks to Nick Warburton for his assistance. Photo used with kind permission of Stan Endersby.