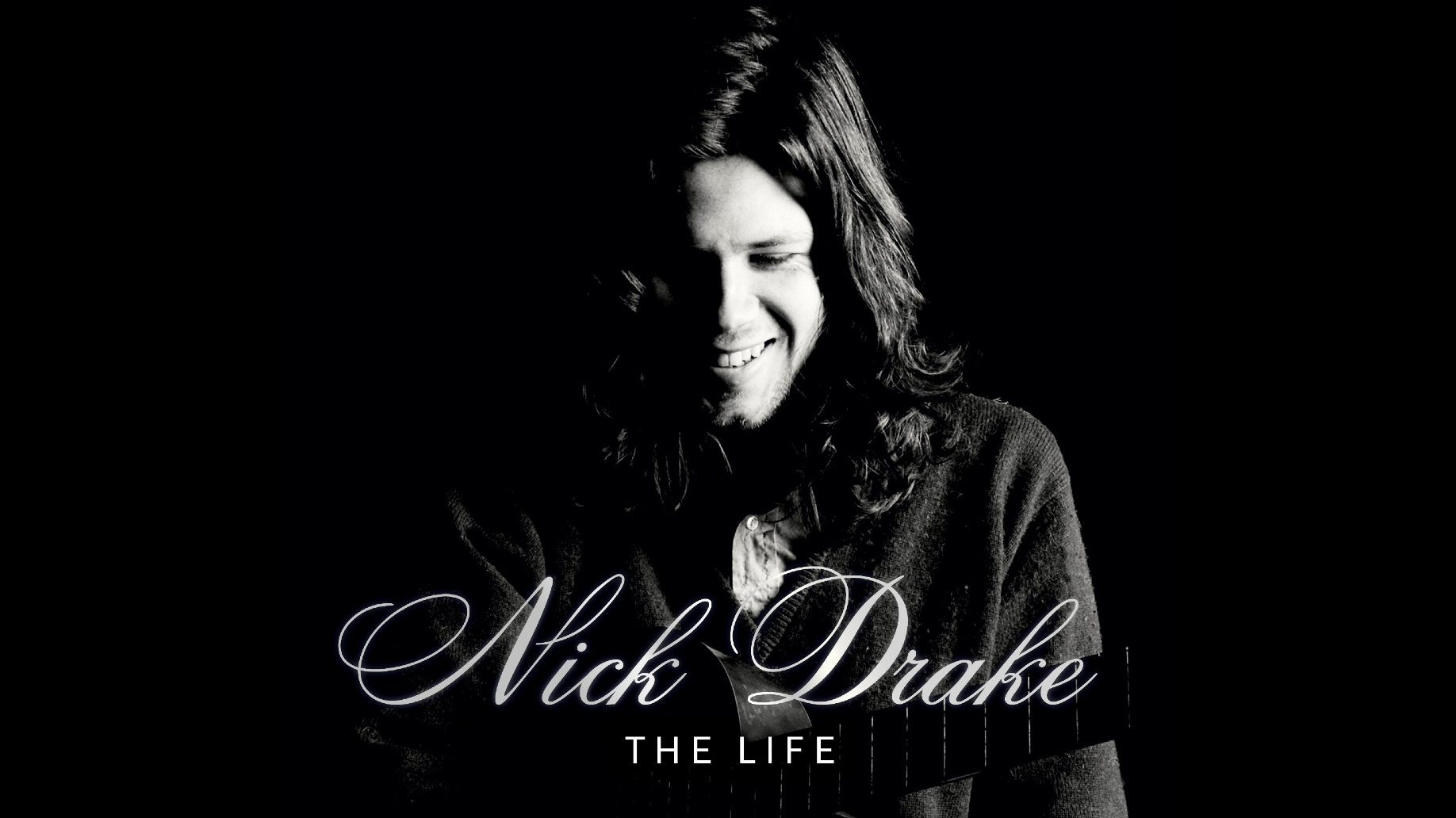

Hi Richard, Nick Drake: The Life is a really important book in the Nick Drake story in that it’s the only biography with the blessing and involvement of Nick’s sister Gabrielle and his estate.

Yes, it’s the only book that his estate has given their blessing to – but the word ‘authorised’ is a bit vexed, because Gabrielle was always conscious that it carries a whiff of censorship or of control, whereas she’s been extremely free and open with every aspect of the project. So the word ‘authorised’ has been deliberately left out of the title, because we wanted to avoid any sense that she has managed what’s in there and what isn’t.

What was the thinking behind the book?

I feel that Nick is in that small category of artists of his sort who will continue to attract an audience, and curiosity about his life, in generations to come. As such, I thought it would be a useful exercise to speak to everyone still alive who ever knew him, and to try to get the facts straight about him for posterity. When people die young, especially in popular music, a process of mythologisation often goes on, and people want their iconic singers to have been more than human. I wanted to try to anchor Nick more in the reality that he obviously operated in.

I’ve known Gabrielle for a fair number of years now – I put out the Family Tree album on vinyl and helped on her Remembered For A While book. That’s a brilliant compendium, and I wish that every artist I liked had a book like it, containing so many bits and bobs. But when it was published in 2014, I immediately felt it also deserved to be turned into a narrative, and for Nick’s life to be fleshed out with more research. Gabrielle permitted me to do it because I think she realised that if it weren’t done, misconceptions and downright falsehoods about Nick and her wider family would go onto the record and be repeated for time to come.

There’s a huge level of research in the book. Near the start of Nick’s life and going into his teens, you really get a sense of a warm musical family. Even his father Rodney could sing and play piano, but it was his mum Molly who was the prime influence.

Absolutely, and I think belonging to a musical family was a very important influence on him. A crucial fact is that Nick grew up surrounded by the sound of his mother writing and singing her own songs, as well as recording them on the family tape machine. So for him, the act of songwriting, of formulating responses to the world in song, was completely normal. He perhaps wouldn’t have realised until well into his childhood or adolescence that no one else’s mother did that.

I think it’s always been quite normal in the (broadly speaking) ‘pop’ world to be in some sort of conflict with your parents over your choice to be in a group or to start singing or playing the guitar. In that era it was seen as particularly rebellious and countercultural, especially in the social stratum that the Drakes occupied, yet Nick was in the unusual position of being absolutely encouraged from day one to play piano and then clarinet, saxophone and guitar, and also to write his own material. There was no sense in which he had to be furtive or secretive about his songwriting.

There seems to be a family influence in terms of Nick’s songwriting and the quality of Molly’s songs like I Remember. Can you see a connection or lineage there?

Obviously Molly was working within superficially different traditions to Nick, because the songwriting styles Nick was exploring didn’t exist in the 1950s (and arguably a little later) when she was making her recordings. But yes, I think you can detect clear lines between Molly and Nick. I’m not sure of the extent to which Nick would have admitted that, or wanted it to be noticed, but it was inevitable, I suspect.

There seems to be an artistic thread running through Nick’s background and time at boarding school – as well as being into sports, he was in the choir, eventually going from piano and to guitar…

I actually think it’s interesting that he wasn’t – more broadly speaking – particularly artistic. I would have assumed that a schoolboy with the level of imaginative engagement with the world that we can observe in his music, would also have written poetry or articles for the school magazine, or painted, or acted in plays, whatever it might be, seeking outlets for that creativity. But Nick didn’t do any of that, really – the bare minimum. His creativity in terms of output seems to have been very much limited to the songs that he wrote and recorded.

But I think it’s important to emphasise that he did thrive at school, at boarding school. I can’t speak for his every moment of the day from beginning to end, but objectively, from the outside, it seems that he was nothing but well-adjusted and in a good gang of mates at the school he went to before Marlborough (when he was eight) until he left Marlborough, aged eighteen. It doesn’t seem to have been an environment that stifled or upset him, and his songs don’t seem to come from a place of emotional disquiet on the basis of being sent off to school, as has sometimes been assumed.

He’s often badged in the folk tradition, but where there is the influence of folk it isn’t English. It’s very much American.

Absolutely. I think that’s important. Nick wasn’t a ‘folk’ singer, but that word gets used now simply to mean anyone who uses an acoustic guitar. It’s a perfectly useful, catch-all term – but in Nick’s case it doesn’t mean traditional folk, finger-in-the-ear, sea shanties, or the pagan stuff that’s so trendy now. I don’t think Nick particularly knew British folk songs, I don’t think they appealed to him. I think with Nick being English, of course the American stuff seemed more glamorous and more foreign. The image of beatnik-style dropping out and strolling down the highway with your guitar on your back was obviously very appealing to a privileged schoolboy at a boarding school in the middle of nowhere in the countryside. So I think that’s what Nick was drawn to.

1964, 1965 was when he was starting to take the guitar seriously, and one thought I was grateful for when it dawned on me was that Nick knew all these American songs, and learned almost all the ones that we know he sang and played, from Peter, Paul and Mary. There’s been an assumption that he was steeped in Delta blues or Bukka White or the traditional folk canon, going up and down to London to buy obscure records from Dobell’s and so on aged 16. But, sure enough, look on the back covers of the early Peter, Paul and Mary records and there all those songs are.

Peter, Paul and Mary were of course hugely influential in their time. Now they’re not listened to so much – we feel the influence of their records more than the power of their own interpretations – but at the time their recordings were how a whole generation of kids like Nick, who had just bought their first guitars, were engaging with American counterculture and of course broader things like Civil Rights that were so important to that generation. I don’t think Nick should be seen as a ‘folk’ singer, but of course he sang folk songs because that’s what you did with a guitar in the mid-60s – no one would have been writing their own arrangements of Stones songs or whatever at that point.

Your book describes events that I certainly didn’t know about. Before Nick went to Cambridge he spent time at University in France, and also went over to Morocco, and there’s a remarkable moment where he meets the Rolling Stones in Tangiers and plays for Mick Jagger.

Yes, that was an important experience for Nick because – as for many of us – it was his first true piece of independence, when there’s no one there to tell you what to do, what to wear, where to be, what to be achieving with your days or weeks. The University at Aix was a taste of that, because he was free of his parents and school and so on, but he was still within a structure of supposedly having to go to lectures and so on. But after not much more than a fortnight he disappeared with a group of new friends and acquaintances to Morocco, where he just did what he wanted for the first time in his life.

And, as you say, one of the adventures they had was encountering the Stones, who were also in Marrakesh. Nick was prevailed upon by another member of his party to go and play for them in their hotel, which he did. And what’s interesting is that it’s a corrective to the image of his being absolutely unable to perform without being crippled with nerves and stage fright and all this sort of stuff. I mean, here we have Nick, aged 18, already a fine guitarist but not yet much of a songwriter, performing quite happily in front of Mick and Keith, perhaps the two most intimidating individuals imaginable in that context. I mean, maybe John and Paul would have been more intimidating, who’s to say? But absolutely two of the most intimidating, certainly in terms of the image they projected.

And he did it confidently and stylishly, by the accounts of those who were there. And at the end Mick said, ‘Come and see us when you’re back in London’ – which, as Nick’s friend who described it to me said, I doubt Mick said to everyone. So I think that interlude in Morocco did have a certain power for Nick beyond just being fun. I think it was where he found a lot of confidence and a sense of mission, where he realised that people who had already achieved what he wanted to would potentially give him respect and help.

At that time in 1967 there were elements of busking as well, and Nick started to write material. Some of the songs that people are familiar with now, like Strange Meeting II, started to come in. So his songwriting started to form?

Yes, absolutely, though it’s hard to know exactly where and when he began to write songs. I mean, he began to play guitar at the tail-end of 1964, so he was certainly a good guitarist by this point. But his first songwriting attempts are almost certain to have been – as for everyone – a bit derivative and superficial, probably not things that he would ever have shared or wanted to survive.

I didn’t see any evidence of earlier songs than the ones he wrote in France, no notebooks, no home recordings… But then again, I didn’t see any evidence of anything beyond the songs we know, really, because Nick always had such a high threshold within his own creativity for what he considered worthy. He played the guitar restlessly, he was always noodling on it, and I think he simply got rid of anything he didn’t like, or twisted it into a new shape. He was probably quite thrifty with his songwriting, and bits that didn’t work in one iteration he’d move into another. I suspect there wasn’t much wastage – when he hit upon something he liked, he incorporated it into something he was building.

We don’t really have much of a clue as to Nick’s genesis as a songwriter, so the illusion is that when he did start writing songs that we know of, in Aix, they were bizarrely good right away. But it may be that he’d already been working very hard for a year or so on material that he jettisoned. Be that as it may, the first songs we can definitely say Nick wrote and that survive are really very good – good enough to have been recorded and released at the time.

In that period the quality of the songs really went up a notch. Time Of No Reply is up there in the top tranche, and that’s a song that has references to the theme of difficulty in communicating.

Yes – I’m a bit hesitant to treat Nick’s songs as crossword clues. I think, as one or two of his friends have said to me very confidently, that his lyrics were often happy turns of phrase that he threw out as he was playing and singing and that stuck, rather than being carefully considered works of literature, as it were.

But I agree that there is, from the start, a definite thread in his songs of being an onlooker, finding it hard to interact, references to girls who seem otherworldly and can’t be reached. And there is, as you say, a striking sense of stillness and isolation. But of course, there are also happy little love songs and other themes that contradict that, so I’d be hesitant to say that as of the age of 18 or 19 he was already psychologically trapped. I think that was to an extent a pose that a young man found appealing or comfortable for his image at that point.

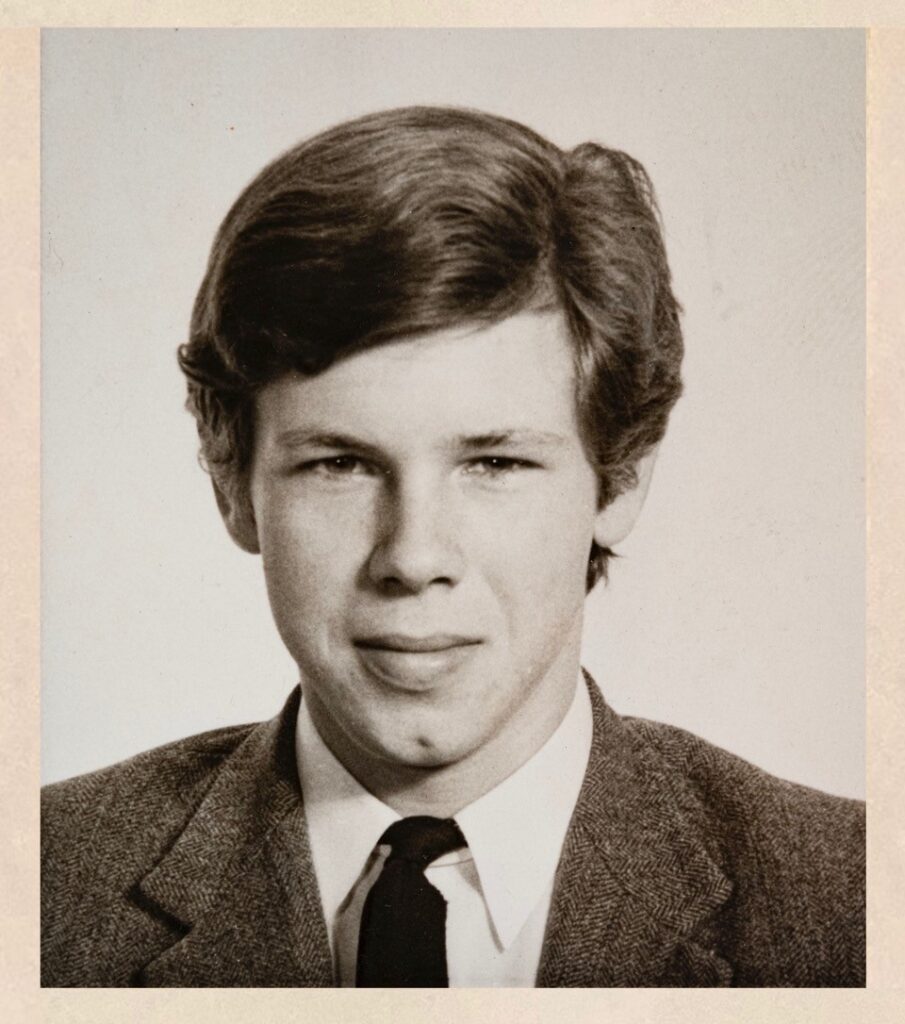

How did Nick find the shift going to Fitzwilliam?

I think it was the most obvious example of him living up to other people’s ambitions and intentions for him. I suspect he never wanted to go to university. He didn’t place any value on intellectual snobbery, I don’t think he cared how he was perceived in terms of academic achievement. He had performed pretty poorly academically throughout his school days, and getting him into Cambridge was an absolute squeeze. And Fitzwilliam was a very new college, quite distant from the centre of town, where the ancient colleges are. And Marlborough had a back door into it, in a way that doesn’t exist now. Back then there was quite a lot of discreet communication going on between teachers who were friends with certain professors and so on. You know, ‘This is a good chap, and he’s a jolly good rugby player’. A lot of that used to go on.

So Nick was somehow squished into Cambridge and turned up reluctantly in October 1967, slightly startled to find himself back in tweed jacket-land, having to be in certain places at certain times, to make notes at lectures and so on. But I think it’s really easy to be judgmental about his parents here. I don’t think any parents, then or now, would have said to a son aged 18, ‘Why don’t you just not go to university and not do anything structured? Why don’t you just be an artist? Because you’re obviously quite good at it.’ In hindsight, yes, it might have been great if he’d been made to feel completely free to do whatever he wanted, but I don’t think that’s reality – and his parents were much more supportive of his musical talent and ambition than they might have been.

By that point Nick was very much focused on writing songs and singing them, and knew that that was where he was most comfortable in life. So Cambridge was a pain in the backside for him, basically. But what we have to be grateful for is that Cambridge gave his life a structure that very much informed the creation of Five Leaves Left, and – needless to say – it’s where he met Robert Kirby, with whom, of course, he worked very closely. Being at Cambridge gave him the time and space to sit around with Robert for as long as they liked, in lovely surroundings, in Robert’s college, working away on the songs.

So whilst Fitzwilliam and the concept of Cambridge was anathema to Nick, I think by the time he left, it had given him strong benefits. I think we should all be grateful he went and that his parents did at least get him there, because I’m not sure that he would have made the music he did without it.

Adding strings to material is quite a balance. If it’s done in the wrong way, it can be syrupy, for example. That’s not the case at all in the collaboration Nick had with Robert.

Robert had such a large influence on Nick’s work – not just as an arranger and a subtle suggester of ways in which Nick might take a certain song, but as an encourager, as a champion. It’s a misconception that he would simply write an arrangement and say to Nick, ‘Here you go, I’ve put it in your pigeonhole’. It was absolutely a collaboration. Robert gets a sole arrangement credit on the sleeves, but in a sense that was generous of Nick, because he knew how to read and write music himself, and the arrangements were written together. Robert’s own accounts of the arrangements being written make it clear that the process was absolutely collaborative.

In those days – I’m not talking about George Martin, but in general – the standard was that an arrangement would be written quickly, played by apathetic professionals who were probably wearing dinner jackets, rushing off to be in the pit of a West End theatre or whatever it was, and then simply sat on top of a backing track. Where Nick’s songs really benefited from Robert’s involvement is that the arrangements were absolutely integrated with the songs. And what’s interesting, hearing one or two recordings that survive of Nick playing the same songs without the arrangements, is that he simply leaves the gaps and continues to play the guitar where the arrangements should go. I think those arrangements weren’t separable from the songs for Nick. I think that was part of the reason that he found performing live so unsatisfactory – he didn’t really know how to play the songs without the arrangements. They’d become fused for him, absolutely part and parcel of his conception of the songs.

Just to steer a bit ahead, when people say, ‘Oh, wouldn’t it have been interesting to hear Pink Moon with arrangements, I wonder what Robert would have done,’ I think they miss the point. The songs on Pink Moon were never going to have arrangements because Nick knew himself well enough as an artist. They weren’t songs he wanted arrangements on.

It was Ashley Hutchings, then of Fairport Convention, who saw Nick live and tipped Joe Boyd off, which ultimately got Nick signed to Island.

What’s lovely about Nick’s story is that there are moments of pure serendipity. I suppose most artists have them, but for Nick, he’d spent his first term at Cambridge bashing along with his guitar in his room, instead of engaging with his studies or the social life of the college or the sporting opportunities that were available to him. These were the things that in theory he would have been doing and that he’d claimed he was going to do in his application. And simultaneously some of Nick’s friends in London, new friends from the summer of ‘67, whom he’d only recently met, had become involved in an idealistic endeavour to raise funds to create an arts centre for underprivileged children.

Under the name of Circus Alpha Centauri, they put on a week of events – films, music, dance, poetry, a children’s party, etc. – at the Roundhouse in North London in the run-up to Christmas. And because they were short of people to fill up the bill, they said to Nick, ‘Do you want to do a spot, mate?’. And so that’s how Nick, by pure chance, came to do this. And the luck for Nick was that Country Joe and the Fish were playing their first ever British dates there that week. So he was on the same bill as Country Joe and the Fish, on the Thursday. I think it’s hard to convey now, but in the UK in 1967 those San Francisco bands were almost like mythological gods. It didn’t seem possible that a taste of that Californian magic was coming to cold, draughty old London. And so it was a very much anticipated and well-attended evening. And Nick had this golden opportunity to perform.

And Fairport weren’t performing that night, Ashley just happened to be in the audience because he liked Country Joe and the Fish. And he happened to see Nick. And when Nick was milling around in the audience later, Ashley happened to catch sight of him again and go over and say hello. So Nick’s first ever live performance led directly to his recording career. I can’t think of any other recording artist of his calibre who owes their recording career to being spotted at their first ever gig. So yeah, that was luck – but also, of course, an indication of how charismatic a performer he was.

Further information

Nick Drake: The Life by Richard Morton Jack

The final part of this interview is available here: Nick Drake: The Darkness Can Give The Brightest Light

The audio podcast version will be available soon.