Del Bromham, the driving force behind Stray, is a true survivor. In 2023, he and his band continue to keep the flame burning with their new release, About Time. This album is a masterful blend of pile-driving rock anthems, soulful slow numbers, and those unmistakable touches of psychedelia and progressive rock that have long defined Stray’s eclectic sound. Jason Barnard’s candid interview with Del kicks off by exploring About Time, then covering Del remarkable story from Stray’s formation in 1966 to present.

About Time, has a usual mix of acoustic songs and tracks with a harder edge – that variation in feel that Stray are known for.

Yeah, I’ve always been a song man, a verses and choruses man. I think everyone has a different approach to doing these things. You may feel that there are some similarities with the old albums to this one. I think it’s partly to do with the fact that Simon Rinaldo, for example, who plays keys and produced it, and well, all the other members of the band were, if you like, fans of the old band. It wasn’t anything where we thought, this is what we’re going to do. It just came naturally. And we realised, oh, hang on a minute. This won’t alienate the ones who used to come and listen to us years ago. As you know, it’s been quite a gap since the last studio album to this one. But it just feels that we’ve got back on track again. And the band, when we’re playing live, it’s probably the best it’s ever sounded. With Simon as well, in the old days, I used to play keys on the albums. But unless I was ambidextrous, I couldn’t do two things at once. So he’s adding that extra colour to the paint box, as it were, live. In the way he’s come in, not only as keyboard player, but as producer, he’s actually seen things in a slightly different way without actually detracting from what we were aiming to do.

It does. The album kicks off really well with I Am. It’s a really strong track that is up there with the material that you were doing in the 70s.

Well, thank you for that. It’s a funny thing actually, because when we discussed doing the album, I had a couple of songs and I didn’t think that the guys would go for that one. I thought they might think it’s a little bit light because we were talking about doing more of a rocky kind of album. And of course the first song I give them, I’m sitting there with an acoustic guitar and I thought they’re not going to like this, but I liked the song. I believed in it and I thought, well, I’ll play it for them. Here’s a new record I bought. Do you want to hear it? You know, and it was kind of, I want them to hear it. I can remember Simon and Karl turned to each other, looked at each other, looked at me and said, “We’ve got to do that one”. And I said, “I didn’t think you’d like that one.” They said, “No, we’re doing it.” I was under orders then. So that’s how that one came about. Almost a mistake. It almost didn’t happen.

Stray are known for their timeless riffs, those instantly accessible ones. Black Sun is a great example of that.

Yeah, once again, as always, the song came first, but I don’t know where these things come from really, they just sort of sit in your head and I just felt it was a good idea. If this sounds a bit contrived, it doesn’t mean to be, but I actually did want to, maybe if it had got enough success, have young guitarists going in the music shop and playing that as opposed to Smoke On The Water. That was my silly idea, so I thought, a nice guitar riff to open it up, will do nicely, thank you. So that’s how that came about.

We talked about the diversity musically, but lyrically you’ve got different things on there. Shout, has that got a bit of a political edge as well?

I suppose it is really. I mean, I’ve always said that probably in another life, I might have been a medieval wandering minstrel telling stories of the time, like they used to do. But with that one, it was just certain programs I like watching, whether I actually enjoy watching them or not, I don’t know. But for example, Question Time, BBC TV, on a Thursday, you’re trying to watch it, trying to get some kind of opinion on some of the politicians that are on there. And I kept watching these programs, and I never actually heard any debates. All it was, was people shouting at each other and shouting the next one down. So no one ever got a chance to talk. And then, even in public, it’s almost like the art of conversation is diminishing because if you want to put your point over, just shout loud at the next bloke. So that was kind of the idea behind that song. It wasn’t aimed at anybody in particular, but it’s just what seems to be the way.

I agree with that. A Better Day, that’s got that undercurrent of optimism, do you think?

It was. We recorded the album when I started writing those songs right in the heart of COVID. We were midway through the second tour we had done. And I think it was March the 6th, we were told, right, that’s it, you’re not going to be playing anymore. There was a lot of bad stuff in the press and obviously it’s easy to talk about things now in hindsight. But at that time, it looked like it was going to be a very dark period and nobody had any answers. Nobody had new cures for COVID, they didn’t know what was going to happen. I just remember watching TV one morning and it didn’t seem very optimistic. And I thought, well, what’s going to happen if we get out of this? But there was still an undercurrent of people who were saying, no, we’re going to be okay. It’s almost like that old human spirit, it doesn’t matter what it’s like to the day, tomorrow is going to be a better day. Maybe someone would have written the same thing during the Second World War, or during war zones, there’s going to be a better day. It’s that human optimism.

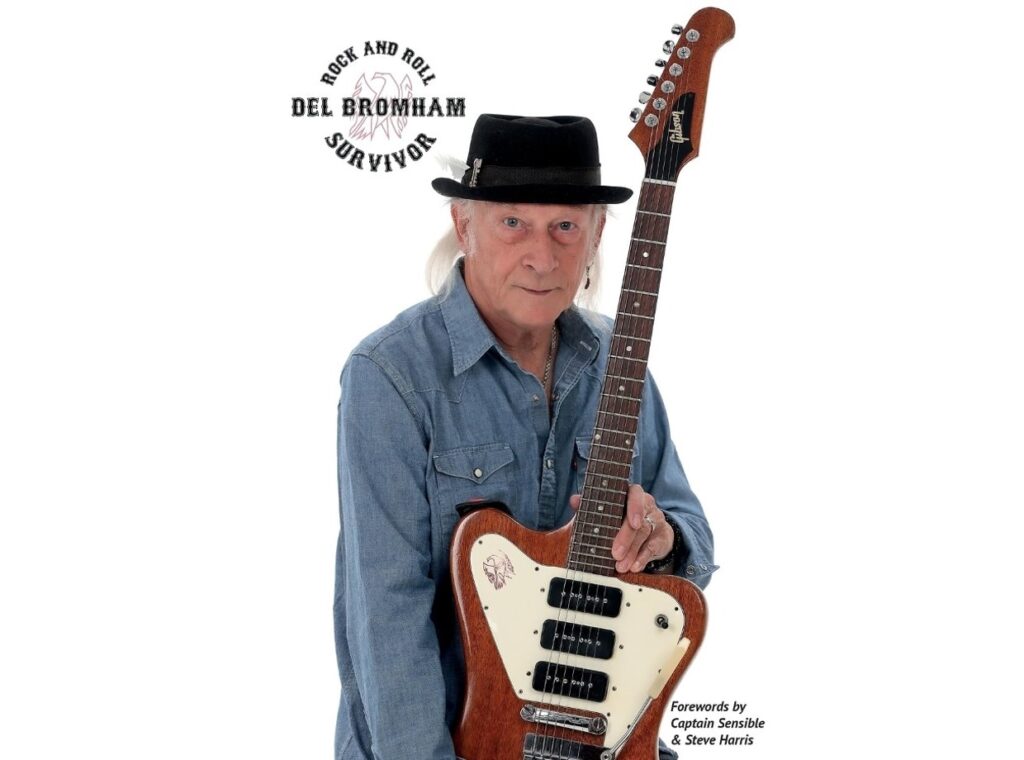

You’ve also got a new autobiography out. Was that done in a similar period? Was it in the pandemic where you weren’t able to do live dates, so therefore you reflected back?

Yes, it was actually. I always make a point when we do shows to go out to the merch store or whatever and meet the people and hear their stories. The amount of times people say to me, you should have written a book. My partner, Annie, we were sitting in doors one day and we’d been together for nearly 20 years. I thought she would have heard all my stories and one night we were sitting there. She’s on one settee, I’m on the other settee. I came out with something. And she says “Oh, you should write a book. I didn’t know that.” I said, yeah, of course you did. I said, “No one would be interested”. And she said, “Well, if no one’s interested, your two grandchildren would be.” It was coming up to my birthday. And I thought, I’m not gigging. Okay, I’ll start writing something. And I thought, where do you start with something like that? So in the words of Julie Andrews, let’s start at the very beginning. So I did that. And it’s just like the blank page on there. And I did start at the beginning from when I was born and things like that. And I think in a book, somewhere along the line, I put on there, I apologise for it not being in chronological order. It’s almost like a conversation. You do one thing. You say, oh, that happened as well, didn’t it? And it was jumping backwards and forwards. I got the book deal almost immediately, which surprised me. They did about 300 signed autographed hard copies. They just printed 300. Because I think they were, I don’t know if they were pessimistic or optimistic, but it didn’t seem a lot to me in the big picture of things.

Wymer Publishing had done it. They rushed it out because I was doing a show at the Stables Theatre. Rushed it out, got it printed. This was November. Jerry Bloom, the boss at Wymer said “We’re giving you 300, they should last you till March”. It sold out in 10 days. So they brought forward the paperback and they gave me another 300, which went in about a fortnight. So before it even got in the shops, it’s been selling since last November, quite well at my shows and on my website and Wymer. But now it’s gone out to Amazon and Waterstones and all the other usual outlets. It surprised me. It might be something to do with the title because interestingly enough, I was thinking at one point of calling it All In My Mind, All In Your Mind, like the Stray song. And the more I thought about it, I thought that it really reduces your audience. Only those who know Stray might twig what it’s about. Then the song I Am came along. And I thought, I’ll call it I Am. Then I thought Rock & Roll Survivor, that’s a better title. And some of them might not have even heard of me. Might say, oh, it’s a Rock & Roll book. So the song came first and I stole my own title. [laughs]

But it was kind of relevant. There are people like me who’ve been doing it for a long time and people like Mick Box as well. I know Mick quite well. And it’s just like, there are certain people who just carry on regardless of what the business throws at you and it can be bloody difficult at times. Because we love what we do and we just keep going. That’s basically what the book’s about, an ordinary bloke from West London wanting to start off playing a guitar. Luckily enough, he still ended up doing it through thick and thin. As Is, the song is about that as well.

You were literally a kid when you started Stray, weren’t you?

Yeah, I was only thinking the other day actually, that some of the information I’ve given out was probably a little bit incorrect because in the summer of 1966 I would have been 14 not 15. It’s always down as 15 years old. But yeah, we were 15 years old really by the time we actually played our first gigs. And we were a pop group of the time, we were doing songs of that time. Our music was a little bit more soul orientated actually which might seem surprising, but The Who were up the road from us. They used to do a lot of Motown, Heat Wave by Martha and the Vandellas. They were doing pretty much the same. There were songs I remember. I speak to Steve Gadd occasionally.

I said, “Did you remember we used to do such and such a song?” He said, “Yeah, we used to do that.” And then we got our managers. The first managers came along Peter Amott and Ivan Mant, they showed us the new bands that were coming up. I’d also been buying albums at the time like The Rock Machine Turns You On, which had a lot of American artists. Through their influence, they got us into places like the Roundhouse in Chalk Farm. I think we were the youngest band to ever play there. I think we were about 16 years old. All in our velvet trousers and white frilly shirts. But the second time we went in, I think I was about 17 at the time. I can always remember one of those light bulb moments I called it. Also on the bill was Spooky Tooth and Family. I’d never seen anything like that before. I just thought that’s a proper band.

Those weren’t the pop groups I’d seen on Top of the Pops. From that point, I actually got what my managers were telling me. Even Spooky Tooth were doing covers of songs, but the way they were putting them over, it was almost like giving their interpretation of it.

Around that time, one of the classic ones is Joe Cocker doing With A Little Help From My Friends. It was how can you make somebody else’s song sound like one of yours? It’s arguably one of the greatest covers, so that’s what we endeavoured to do. Of course, as time went on, we put our own arrangements within the cover song. Then I was thinking, oh, hang on a minute, I’m giving my stuff away. I’ll write my own song. I’d already been writing songs, but I started writing songs in a slightly different way. I was more aware of the lyrics, rather than I love you, it was let’s write a story in music, basically. That’s how it went from there, how it changed from one thing to the other. But as you say, 1966, we were just kids. We couldn’t even buy a drink in the pub where we were playing.

The debut Stray album is such a strong album, so many highlights like Time Machine and All In Your Mind. But was it almost a greatest hits at the point as you’d been collecting quite a catalogue of songs, the band had been honed by those live dates. So you were really ready by the time of that LP.

Yeah, we’d certainly done our apprenticeship. We’d done so many gigs, unbelievable amounts of gigs. But there was something else that I’ve often thought about. Once again, I’ve had this conversation with Steve Gadd about it. I don’t know how we ended up recording the songs we did for that first album because we had so much original material. Why we picked those songs, I don’t really know. Once again, All In Your Mind was one which virtually came together on one of our rehearsals at a jam and we ended up recording that. But we were quite prepared when Suicide come along because we recorded that by the end of that same year. Once again, not only the material we had, there was the other material left over from the first album. Some of those songs still didn’t get recorded. So I’ve no idea how those songs came on there. With Time Machine and even the ballads Around The World In 80 Days, in my mind, I was thinking the first album would kind of be stories, maybe about time travel. Just generally speaking, it obviously didn’t end up that way. But that’s kind of how it started. But I’ve no idea how those songs came on there.

The third Saturday Morning Pictures, the sound broadened out a little bit, so was that, wanting to develop?

Without a doubt. We thought we had got to that point. Obviously, we were listening to more music, a wider type of music. I’d been listening to a lot of the bands and Steve had too with people like The Band, Music From The Big Pink. Just various bands and even like The Faces and Small Faces, I always liked the Small Faces. So I wanted to incorporate more of that old Hammond organ sound that was on there. And also, once again, the songs on there, were stories like Queen Of The Sea and even Our Song, we all wrote that one together. They’re all kinds of stories. And I just wanted to make the album a bit more soulful. I don’t mean sort of R&B soulful, but just, for me, the English band, Free, were a soulful band, you know? I wanted it just to touch you somewhere when you heard it. And Martin Birch, who co-produced and engineered it for us, it was great. We hadn’t met him before, but as soon as we met him and we started playing the songs, he was right on the same page as us.

It was like having the fifth member in the band. And he would be, why don’t you try that? Why don’t we do this? It was far more experimental than the last two. If you’d have asked me, I would have said, well, can I have George Martin producing please? Because I always wanted to be in The Beatles? We did actually do a few experimental things, but Transatlantic Records had the last say on it. There was a version which was never saved on the title track, Our Song. It had strings on it, and a lot of backwards stuff. It was like Stray meets the Beatles somewhere. There were a couple of older chaps in the record label who thought it was a bit too hippie trippy. So we weren’t allowed to have it. And unfortunately, I don’t even know what happened to the mix of that.

But we’d only been about 19 years old when we were doing Saturday Morning Pictures. So in the big picture of things, we were still kids and they said something and we nodded. That was also a nice period actually. It was a happy time. The band seemed to be really taking off at that point. And we actually were disappointed because not being a big head, but we actually thought at the time of recording that, this is the one that’s gonna do it. At that time, all the other bands such as Sabbath, Zeppelin, the Purples, all on the same level as us, were doing the same gigs. And they had that album. And I honestly believe, and I don’t care who it is, I honestly believe a lot of it was because we didn’t have the power of the record label that the other people did.

Same with Status Quo actually. We met Status Quo. We supported them at the California Ballroom when they were a pop group. We were a pop group as well. And then a few years later, they wanted to change their image. It’s a fact that their management got onto our management to say, could we do a couple of shows with Stray because Stray were playing the places they wanted to play. Because they’ve been used to doing all the Mecca ballrooms and things. Once again, they ended up playing to some of our audience, but they had Vertigo, they had the better label. Transatlantic, bear in mind there was us, Jody Grind and Little Free Rock. Transatlantic Records was a folk label, Pentangle and people like that. I suppose we were like the 1970s version of the Sex Pistols for them. They didn’t know what to do with us. Oh, they’re a bit loud, aren’t they? Just the way, fate didn’t work in our favour at that time. There you go.

There’s a little bit written about the management you had, Wilf Pine, didn’t he have some dodgy connections?

You could say that. We were quite naive at the time. Peter Amott and Ivan Mant were our first two managers. I suppose in retrospect, they took the brunt of some of the blame. We were thinking that the record label was maybe not big enough. Maybe the management company isn’t quite strong enough. And then we were offered the nationwide tour with The Groundhogs and Gentle Giant. And there were the venues that we thought we should be in at that point in time. So we got offered the tour and it was run by Worldwide Artists who were run by a guy called Pat Meehan.

And one of the guys who worked for Pat Meehan was Wilf Pine. And Wilf Pine was managing The Groundhogs at the time. And he also was co-managing Black Sabbath. So it transpires that he had noticed that Stray were doing really good business on the circuit. So he wanted to put us on his tour, with the view of offering us a deal. And it worked. He offered us a deal and we took it. In retrospect, it might not have been the right move at the time, but you can’t turn back the clock and that’s what happened.

We had a lot of experiences that we wouldn’t have experienced at other times, in other management. But yeah, it was different. That lasted for about two or three years. It fell apart really when Pat Meehan sold off Worldwide Artists. I think he went into films or something. I think he actually found Wilf on a bit of a loose limb because he didn’t have the Worldwide backing that he had. Financially for us, it was a disaster because all our money was going into the office. We had a posh office in Dover Street off of Oxford Street, London, which must have cost a fortune. And as young 20 year olds, we were doing what we wanted for a living. We were getting a weekly retainer. After about five years of being with Worldwide Artists, we found that none of our tax, insurance or anything had been paid. But going back to Wilf. He was getting involved with the mafia in America.

He’d become very friendly with a guy called Joe Pagano, who was the head of the New York State. He took a shine to Wilf because Joe’s son, who was the same age as Willf, was found shot dead in the back of a car. So he kind of adopted Wilf. It was through that that we got our first American tour. And we did the Move It album in America as well. And that was all with the same connections. But like I say in the book, if you’d have told this young 15 year old from West London that one day he was going to have dinner with Joe Pagano as a head of the Mafia, he’d just say, leave off. Likewise, a lot of the artists that I’ve met and I’ve played with or been on the same bill as over the years, I wouldn’t have got that if I’d have ended up working in a warehouse. So it has its good points as well as its bad. When Wilf finally made his life back and forth from the States, he suggested that perhaps Don Arden would manage us.

And Wilf started his career in management working for Don Arden. When I say working for Don Arden, I think you know what I mean. So I had several meetings which never came to fruition at Jet Records to meet Don Arden, who was going to be my manager. At the time they had Widowmaker and ELO, Roy Wood, Lindsay DePaul. I’d been there several times, then one day I got in there and the A&R man Arthur Sharp said to me, “You never guess who’s coming in here today.”

I said, “No” He said, “Charlie Kray” I said, “Really? What’s he coming in here for?” He said, “Well, he’s not long been out of one of Her Majesty’s hotels and he’s written a book. So he wants to get some promotion and management on this. So I’m sitting in the offices of Don Arden’s office waiting for my meeting. And in walks Charles Kray. I was about 25 years old at the time. I’m sitting there. And, the conversation is something like, “Hello, what would you do?” I said, “I play in a band.” He said “I used to be in the music business”, which he did with his own club, and he said, “How long have you been here then?” Because by this time we’ve been sitting here for about half an hour. I said, “Oh, I must have been in about 45 minutes but it’s not the first time I’ve been here. It’s about the third time I’ve been down there. I’ve never got to see him.” He turned around and said to me, “I don’t know about you, but I don’t like being given the runaround. I know some people in the music business. I could have a word for you.” So I said, “All right, smashing.”

I lived in West London, and he was going to Bethnal Green, the other side of London. And he said to me, “Have you got a car? How do you get here?” I said, I drove. He said, “Oh, you got a car? I said, yeah and he said, “Are you going anywhere near Bethnal Green?” Like I’m going to say no. So I ended up taking Charlie to his mum’s address, a famous address in Bethnal Green. I’m driving my car thinking, nobody is going to believe me. Nobody’s going to believe that I’ve got Charles Kray sitting in that seat. And what actually happened was that we got introduced to Laurie O’Leary, who was well known in the business at the time. And we made all the daily papers, Charles Kray to manage Stray. He was great. He was like “If you’re doing any shows, any single one just call me and I’ll sort it all out.” It seemed a great idea at the time. Unfortunately, the people in the music business didn’t think it was a good idea because we’d already had an association with Wilf Pine. And now we’ve gone to Charlie Kray. There wasn’t an agent who’d touch us.

There were a few agents, one or two agents that were trying to put stuff our way. Then of course, the punk scene came in. And a lot of venues we played at were changing and having the punk bands in. But there’s an irony there because we were the same age as some of the punks and actually younger than one or two others. But we were classed as old school? So, with all the bills and things that hadn’t been paid coming in, by the end of 77, I think it was November the 7th or 8th, we did our last show. We didn’t know it was gonna be our last show at The Nottingham Boat Club. And then after that, because I was a homeowner, I had so many bills coming in, they were after the money. We ended up having to sell all our assets, which was the equipment and everything, just get out of trouble, get out of jail. For me personally, I had to start all over again, which has come all these years later to the About Time album, and it is about time, I suppose.

It seems no expense was spared on some of your albums in the 70s. Mudanzas, there’s orchestration on there, you’ve got the Changes piece opening, then going into Come On Over. It’s very lavish.

Well that wasn’t really our idea. That was Wilf Pine wanting to be the producer, idea. I would be hands up guilty to say that I’ve made noises that I’d like augmentation. I already had ideas for the song on there called I Believe It. That was very much orchestra orientated. Some of the songs I wasn’t happy with. I like the idea of having on Come On Over, the strings, but I think the orchestra drowned out the band. Likewise, I wasn’t very keen on the brass on Pretty Things. Because when we used to play with that live, that was a real hard rocker. And I think that the brass tamed it a little bit. It took the edge off, it started off as Black Sabbath and ended up sounding like Glenn Miller.

So it was a bit odd. In an ideal world, I’d love to get the tapes of that album and remix it. And funnily enough, when Sanctuary or Universal, they re-released all the albums. I was a bit peeved on two counts, really. I’d like to have remixed that one in particular, as I said. But also, on one of the compilations they did, they found two tracks, which were backing tracks. I had no idea they’d done this until they pressed it and sent it to me. And I said, why didn’t you tell me? Because you’ve got a couple of songs on there. One’s called Johnny the other called Paramount.

I said “I wish you had told me. You could see that they were songs and I could have put the vocals on.” Every time that goes on, people must be thinking, what’s the point of that? Just endless chords. But there you go. It’s the way it happened. But yeah, Mudanzas. I said that I’d like to have some orchestra on it. And Wilf actually said to me, “I’ve been introduced to this guy called Andrew Powell.” I said, “What has he done then?” So he said, “He’s just done the Cockney Rebel album.” Well, at that time, I was really impressed with Sebastian, the first single that came out. I thought it sounds like George Martin there. I thought it was a George Martin production with strings. And I found out it was Andrew Powell. On some of those songs, like, I Believe It, for example, I didn’t chart it or anything, but I said to him, I want the bass line, the cellos to follow the bass line. I want you to put your George Martin head on, please. And that’s how that one came about.

We had Alan O’Duffy on. He had a good ear for vocal harmony. He’s on Oil Fumes And Sea Air with the high vocal harmony. He said, “It reminds me of The Hollies. I can do Graham Nash’s harmony. I said, “Go on then. Off you go.” I think a lot of money was spent on that album. In fact, we did some of the demos at Escape Studios. So we had half of it recorded, and then scrapped it all and started again. I’m not sure why we scrapped it all. It might have been something to do with somebody not paying the bill. No names or anything, Mr Pine, [laughs] but it might have been something to do with that. Anyway, yes, it was quite a lavish production. I don’t think it necessarily worked 100%, but you do these things and it becomes part of your footprint.

On Stand Up And Be Counted, there’s a song Waiting For The Big Break. Is it that as we get into the late 70s, one of the frustrations is, a lot of the bands that supported Stray have kind of gone past. You were on equal footing. The albums were great. You had a following. You went over to the US at times as well, but you just didn’t get that spark that tipped you over.

Absolutely right. You understand the lyrics perfectly. It just seemed like, as I put in there, we all did disappear down the hole in the middle, you know, and that was partly due to working with Transatlantic Records. It wasn’t really getting us anywhere. It was I guess, a frustration song. But that album actually was almost a mistake as well, because when we went into the studios to start recording that, Steve Gadd was with us. And he was really adamant that he wanted to do his songs. He wanted to do his songs his way. And they were so different from what we were doing. And there was a lot of friction in the band. He was a singer and it was an awkward position for me because I was writing the songs, but he refused to sing them.

I’m thinking, well, you’re the singer and you don’t want to sing the songs. So apart from the frustration, as you pointed out in that track, Waiting For The Big Break, I remember, this is a bizarre story, almost like I’m making it up, but I swear to you, it’s true. During that recording, that session on that day, Richie Cole, the drummer, and Steve almost came to blows. And I’ve never seen nothing like it, because we were like four kids together, we were so close. I went home and I said to my wife at the time, “I don’t think I can be in this band anymore.” I didn’t feel there was a place for me, songwriting was my main thing. I said, “I think I’m going to leave, quit the band.” She went, “You sure?” I said, “I think I’ll quit the band. I’ve already been talking to Wilf, and he wants me to do a solo album anyway.”

10 minutes later, after I made that statement, my phone rang, and it was Gary Giles, the bass player, he said to me, “I’ve been thinking, Del, I’m going to quit. I don’t want to be in the band anymore.” I went, “Well, it’s funny, you should say that because I’ve just said the same thing here.” 10 or 15 minutes after that, my phone rang, Ritchie Cole, the drummer phoned me and said “I can’t have another day like that again. If I’m not good enough to be the drummer of Stray, I’m going to quit”. I said, “Hang on a minute. I think we better have a chat.” Basically, we phoned up Wilf and said, “We’ve got a problem”. We went to our manager’s office, and we sat down, and he actually said, “I’ve noticed Steve seems to be on a different track from you at the moment. I want you to go in and continue recording the album.” He said, “I’ll take care of Steve, and I’ll manage him as a solo artist.” We did that. I said, “Ok, then.” Gary and Richie looked at me and said, “What songs have you got?” I said to Wilf “I’ve got the songs I was going to do for the solo album.” He said, “You better start recording them then.”

The Stand Up And Be Counted album was almost my solo album. We went in there, and the first song we did, which was quite not like Stray of old, was Stand Up And Be Counted. It was me at the piano, Richie and Gary playing bass, and then I overdubbed the guitar on. I’d always said to Wilf, “This one needs an orchestra on it.” We’d done about two or three days recording on our own, and Pete Dyer had come in, he was a friend of mine, had played backup guitar on a couple of the live shows, because Steve we persuaded Steve not to play guitar, go back to what you used to do. Steve was insistent that if his guitar wasn’t there, it wouldn’t sound as full. Pete came and did a couple of songs. In the end, it was almost like, I don’t want to sing all the songs. I’m not the singer. I’ve never sung before. So we called Pete in to join our band. Pete joined from Stand Up And Be Counted and ended up singing some of the songs. I said you sing that one, you sing that one and I was just directing it and what to do. Twin lead guitar bits that we hadn’t done before. I’d always taken care of work myself and that’s how Stand Up And Be Counted was recorded. Another accidental album because it should have been my solo album.

When did your paths cross with Ozzy Osbourne? He wanted to produce you at one point, didn’t he?

He was signed to Worldwide Artists and Wilf. We had met him before and we were playing in the Starwood Club, which is in Hollywood in Los Angeles. And he came along, and I could see him standing right down the front. Then he came backstage. He said [mimicking Ozzy] It was great. I want to produce you!” We had one or two little escapades with Ozzy. But he wanted to do it and I think Wilf wanted him to do it because it would have been good for our career. I think Ozzy was looking for another avenue as well as being a singer. At that time, most musicians tried to branch out as much as they could do. But for whatever reason, it didn’t work out. That was 1975.

When it comes to about 76, I think Black Sabbath were having problems. That may well have been the same problem we were having, which was a financial one. I think they lost a lot of their money. As time went on, you’ll see that Sharon, who was then going out with Ozzy and Don Arden took over the management of Black Sabbath. I think she could actually see that her own father was ripping her boyfriend’s band off. So that caused that bad thing. So going back to the production thing, I don’t think it happened because there was so much other stuff going on in the background that we didn’t know about. But ultimately we found out.

Going forward after the break-up, when did you become aware of Steve Harris and Iron Maiden’s love for Stray?

I was sitting at home one night, and I’ve got a bunch of friends, and we always take the mickey out of each other. You never know if someone’s gonna phone up, tell you it’s Jimi Hendrix on the phone. I was sitting in my house one evening, and my phone rang, and my wife picked the phone up, and she said “It’s Steve Harris on the phone, from Iron Maiden”, I said “Yeah, of course it is!” So I went over to the phone, I said, hello, thinking it was my mate. And he said, “It’s Steve Harris here.” I thought, oh, I think it really is Steve Harris. And he said, I just thought I’d give you a call. We’ve got a new single coming out called Holy Smoke, and if it’s alright with you if we record All In Your Mind?” Then he started to tell me what a big fan he was of the band, and how he and his mates used to come along to all our gigs when we were in London, and see us play. Not long after that, it was the first show they did, I think with Janick Gers playing. Steve invited me along. I said, “I didn’t realise you’re looking for a new guitarist, I said, you should have phoned me!” He said, “I didn’t know your number at the time.” We’ve had a little joke that I was the Iron Maiden guitarist that never was, because he didn’t have my number. Whether that’s true or not I don’t know, but it’s a little running joke we’ve got.

But I’ve become very good friends with him, and various members of his family, and it’s quite humbling. I have chats with people at the merch, and quite often you meet young guys in bands who are playing. I just tell them, you never know who’s in the audience. I’ve met so many well known people now, who used to come and see Stray play, and you just have no idea what’s going on. But Steve, he’s a lovely guy. He came to one of our shows actually, we did Leos at Gravesend a couple of weeks ago, and he came along to that. He loves the new album as well, so that’s good to know, I’m still keeping it in the family. We have talked about possibly in the future doing something together. So, you’re the first to hear that, that’s an exclusive. But I don’t know if and when that’s going to come about, because he’s busy with the Iron Maiden shows that are coming to an end. I don’t know what’s happening there, but he’s very busy with British Lion. We actually did play a couple of shows with British Lion, it went really well. But it’s just a really good friendship that we’ve developed. It’s very humbling to know that someone like that is a fan. I think he knows more about my albums than I do. [laughs]

As well as About Time, you’ve been doing some dates with John Verity, the Verity Bromham Band and I’ve been seeing clips, you’ve been doing a tribute to Bernie Marsden, Ain’t No Love In The Heart Of The City. So it seems that you’ve been playing with John a mix of favourites.

That was another strange phone call out of the blue. It was just coming when gigs looked like they were starting to come back again. I’ve known John for years, not really well, not as good friends, but we used to bump into each other at gigs and things like this. It transpires. I didn’t realise at the time that he isn’t even very far away from me either. About 25 minutes away from me. He’s very close. And I got a call from Peter Barton, who’s the manager of Rock Artist Management. Peter Barton gets these ideas, he’s very much an ideas man. So he said, “You know, John Verity, don’t you? Could you do some shows playing some covers, songs from like when you were first starting or whatever?” I said, “I don’t know,. It’s a nice idea. But you can see bands do covers in pubs anywhere. He said, “No, I think it’d be interesting to see what you two would do with it.” I spoke to John, then Peter said “That idea I had. I’ve got you a spot on the Colne Rock and Blues Festival in August” I went, “Ok, John, we got a gig.” So anyway, we had a rehearsal. We used the drummer he’d been using, Chris Mansbridge and we were going to use this particular bass player.but he was busy on tour with someone else. I said, well, the other best bass player I know is the guy who’s playing in my band now, Colin Kempster. So that’s the route we took. His drummer, my bass player. And I’m not kidding you, we picked a handful of tunes, we played them and it was like we had always played together. I’ve got to know John really well now. It’s been a lot of fun.

But going back to the Colne Festival, we did that one and I’m thinking, I still don’t get it, we’re doing all these covers. We didn’t do any original songs on that particular night. We just did a bunch of covers and we went on, on a Saturday or a Sunday afternoon at five o ‘clock. We went on after The Animals who were doing an hour’s worth of well known tunes. And I’m thinking they’re going to love us, me being pessimistic! I walked on stage, walked up to the microphone. I said, “Now listen, I want you all to think it’s about 10 o’clock at night and you’ve had a few beers and you want to have a sing along with us. Well, we did our set and it went down a storm. I can always remember coming off stage. John had got to the dressing room before me. We looked at each other and I said to him, “What happened there? He said, “I don’t believe it.” I said, “I know. I’ve been 50 years playing my own songs. We went out there and did a load of covers and it went down great.

Then a little while later, we played the Carlisle Rock and Blues Festival. Same thing we went on, it went down an absolute storm. Funnily enough, you mentioned, Ain’t No Love In The Heart Of The City. I’ve got the whole audience singing along with it, I’ve seen it on film somewhere. And the promoter said, it’s one of the best I’ve ever seen a band go down, you’ve got to do it again next year. So we’re doing it again this year. But we ended up doing kind of word of mouth shows. It was people saying, “Oh, you’ve got this project with John Verity, don’t you?” So we ended up getting a few more gigs, which actually needed a longer set. So what we’ve done is, people said to John, “You haven’t done any of your tunes” and to me “You haven’t done any Stray tunes.” So we learned a few of each and we did The Stables in Milton Keynes, some originals and some covers. But everywhere we go, it’s gone down well. I talked to musicians after one of the festivals and I said “I don’t get it, it’s going down so well” One of them said “You don’t get it. People are interested to see what you do with those songs.” So that was almost like another accident. I’m accident prone. That’s my problem. [laughs]

I think there’s quite a lot of talent there as well Del. Thank you so much. It’s been a pleasure to talk to you. And you’ve got so much on. You’ve got the About Time album. You’ve got your autobiography, and as well as dates with Stray and John Verity. I don’t know how you find the time!

Oh, it’s a horrible job, but someone’s gotta do it! I’ve always enjoyed playing. If I get the opportunity to play, and I mean, I’ve lost quite a lot of money over the years doing this but the point I always say is when I was about 11 years old and I picked up my guitar, I picked it up to play it because I enjoyed playing it. I didn’t think I’m going to pick this up and play this because at the end of the night, I might get 10 quid.

I mentioned Mick Box earlier, I think once you’ve got that desire, that’s the difference between some musicians and others. Not blowing my own trumpet, personally, I’m just saying I think that’s the difference. Some people see it as a business, and other people see it as a love. The journalist Dave Ling once said after he’d interviewed me, “If you don’t mind me saying so, Del, for a gentleman of your age, you’re in quite good condition.” I said, “Thank you very much.” He said, “Do you think you’ll ever retire?” I said, “No, I’ll probably be the BB King of Buckinghamshire.” It was in 96. He said, “Can I quote you on that? That’s one of the best quotes I’ve heard.” So unfortunately, if you don’t like me, you’re going to have to put up with me for the next 20 odd years. [laughs] I’m going nowhere.

Further information

Stray’s new album About Time and Del Bromham’s autobiography Rock and Roll Survivor are out now. Details can be found on the Stray and Del Bromham websites.

Verity Bromham Band dates and tickets are on John Verity’s site.