Step into the world of Pulp as we embark on a journey through the eyes of their drummer, Nick Banks. Nick spoke to Jason Barnard about their years as outsiders in Sheffield, rise in the 1990s and what exactly they did as an encore. Along the way Nick also takes us on a behind-the-scenes exploration of Pulp’s greatest hits and fan favourites. This interview is taken from a 2019 Strange Brew Podcast with Nick.

The first track I wanted to ask you about is one that you’re synonymous with, ‘Babies’. That was, I think, in one of the demo versions known as ‘Nicky’s Song’. Is it true you developed the guitar riff?

Well, you’re partly right there, partly wrong. ‘Nicky’s Song’ was a different song entirely. I can see why you might think that. Because basically, yeah, I was the germ of the song idea. And we used to do lots of different things to create different or to try to start off songwriting, lots of different techniques. And one of them was swapping instruments. So you’d get a non guitar person playing guitar, etc, to try and generate ideas not based upon musical technicality. It was sort of one of those sessions. We often did that quite a bit. But I think the ‘Babies’ one was I think we’d stopped for a cup of tea. So we stopped for a cup of tea, and I think I’d finished mine. I just picked up Jarvis’s guitar and started playing two chords and having this tea. And then Jarvis said, “What’s those two chords you’re playing there? Well, one of them is G. No idea what the other one is, because being a non guitarist, my chord knowledge is really quite limited.

I said, “Well, that’s G. I know that, but I have no idea what that is”, which was just me holding three strings down on the top three strings with one finger. I think it took Jarvis quite a while to work it out. It’s a derivation of D, I think, anyway. But yes, so I was just playing the main verse riffs, I gave him the guitar back, he started playing that. He added an E for the chorus. Literally 20 minutes after I played those first two chords, we had the entire song, basically. And that was obviously the best example of the swap instruments technique that obviously came to fruition. So I would always like to claim ownership of that song, if anyone would like to claim otherwise! So partially true. The song, ‘Nicky’s Song’ I can’t remember that was kind of whether that was a kind of one done later on, quite what it’s called song now, maybe escapes my mind, but I think there were two different songs, in my mind.

Was that written in the late 80s?

That will have been about maybe the early 90s. It first came out in 93. So it was probably about 91, something like that. It was written in the railway arch at Catcliffe upstairs there, where we had a rehearsal room.

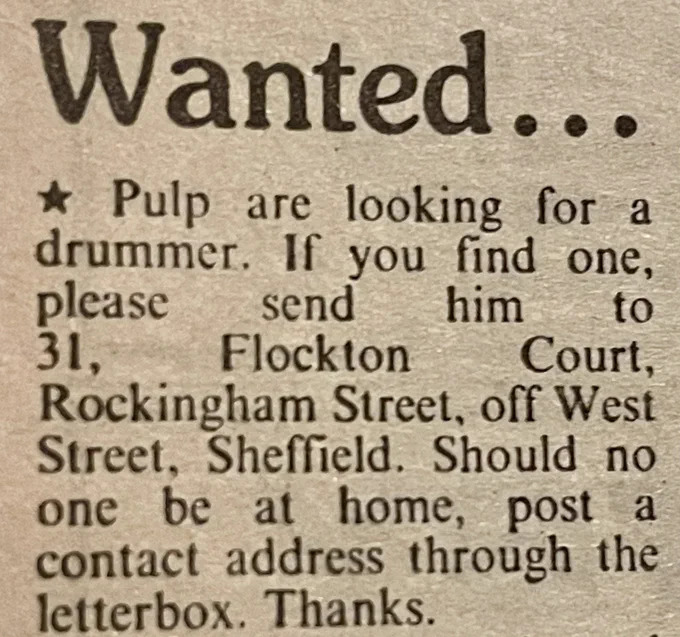

And you joined in 1986?

Late 86 I joined. Freaks had just come out and as is the typical Pulp way, half the band decided to bugger off. So I kind of came in and then it sort of became Pulp version five or something, whatever it was, god knows. But yeah, late 86.

In terms of that post Freaks era, that was a time which marked, I guess, like all the lineup changes of Pulp. It marked a transition in sound. But this one in particular brought a big change from Freaks to more of an electronic and disco thing.

I think changes of personnel are going to bring in different approaches and that sort of thing. My drumming style is quite different to Magnus’s, which is looser, perhaps more florid, whereas mine, I would sort of say was more stompy, which I suppose would lend itself to a more discoified sort of feel. And also that change, a lot of it was driven by Jarvis having a Yamaha Portasound keyboard, which, when he fell out the window and bust his legs when he was recovering at the hospital, I think his mum or his grandma brought him in this keyboard with these rubbish preset disco sounds on. So he started writing some songs using that rubbish disco sound you get on these little portable keyboards. So when one side joined, we basically we’d never played any songs off Freaks at all, and we just worked on these new songs that Jarvis had developed, a lot of them using this Yamaha Portasound keyboard. Hence, things like ‘Death Comes To Town’ and ‘Death Three’, etc. Jolly title songs like that.

Separations came out quite a bit later, ultimately, but there’s some great tracks on there. ‘Love Is Blind’ is quite symptomatic of that shifting sound, but also that more direct style.

Definitely. And also sort of there was quite of a Russell influence in that period as well. An Eastern European bent, ‘Love Is Blind’, as well as a song called ‘Rattlesnakes’ which I don’t think ever got really released at the time. Some very sort of Eastern European stompers.

That’s the violin that he brought.

You could do that in those days. Strange Eastern European type songs. I suppose ultimately it didn’t help us that much because we were still years in the wilderness. But hey ho, you got to try something, haven’t you.

‘My Legendary Girlfriend’, which was the first single prior to the eventual release of Separations. Am I right that it had a mix of drum machine and live drums?

You’re right, there was a mix of drum machine and live drums on that. That was recorded with Alan Smyth, who went on to basically discover The Arctic Monkeys later on in life. We had a budget, but it was still quite a limited budget to record these songs. And a lot of drum machine was employed, basically, so that the budget wasn’t all eaten up by spending hours getting a decent drum sound, because our instruments were pretty ropey, so you’d spend a lot of time trying to get a drum sound. So Al said, “Well, let’s do a lot on the drum machine so we can get a good drum sound cheaply, basically. So we did a lot of programmed drums there and then we mixed in some live stuff as well. All I was concerned with, I’m sure a lot of drummers would have felt that they had their nose put out a joint by the producer saying, “Right, sod that we’re going to use a drum machine.” But I was keen on making a record as good as we possibly could. So if that meant mixing in drum machines, live drums, if it meant doing that, I was all for it. I wasn’t too precious to sort of say, “No, I’m playing on all these records, don’t care.” It was just a case of getting as good a sound as we possibly could. And I think because we listened to it. A few years back when we were rehearsing for the 2011 jaunt, we listened back to some tracks on some really big speakers and we were amazed how chunky it really sounded. So, we had to do that. These things you got to do.

It does feel like that period, 87, 88, leading into 92, marked that shifting shift in the band. And then the sort of guitars start coming to the fore a bit more, a bit like tracks like ‘She’s A Lady’, which kind of blends that more electronic with guitar.

‘She’s a Lady’, we used to play that live, and it was a real stomper. And for our early crowds it really got them going. But when we ever tried to record it, it always just never seemed to be able to capture the excitement and rush of feeling that we get when we played it live. So rather than try and fight against that, we took it the other way and made it more of a kind of electronic feel rather than a live stomper, you could say. You just go try lots of different things, I guess.

Across Pulp’s career there’s a few songs that barely got a release that seemed to fall through the cracks that live really worked. Songs like ‘Live On’ and ‘We Can Dance Again’.

Totally. Certainly ‘Live On’, that was a real crowd favourite when we played it live. But again, we could just never seem to get it sounding exciting when we got it in the studio. So, yeah, it just fell between the stools, as some of them do, and the great lost track ‘Death Comes To Town’, which we thought was nailed on. If we could get this on the radio, this song would be a hit, because we just thought it was fantastic. And we thought, we’ve got a great recording. But of course, we’re having to deal with Fire Records who no one who’s ever come into contact with Fire Records has ever got a good word to say about them. And I would fall into that category myself. So we tried to get it released. Fon Records, who kind of went on to be almost Warp Records, we tried to get them to release it. But because of our terrible contractual situation, they were scared off and it never got released.

And so after a bit, you think, well, that’s not working. And you constantly work on other things. It was in the dark days of when gigs were few and far between and we were on a crap record label with a crap contract that we desperately wanted to get out of but couldn’t really see how to. So, things just do disappear. A shame, really. We could have made it years before we did, but we just didn’t.

Yeah, because ‘Death Comes To Town’, was it the Fon version that eventually got released?

We recorded it at Fon, and it got released on some obscure… It was probably appropriated by the folks at Fire who didn’t really have any contractual say to it.

It seemed the moment for Pulp where you weren’t gigging as much because Jarvis was in London. The music scene seemed to change though. Eventually you also moved down to London as things started to pick up.

Steve was living in London, Jarvis was living in London, we didn’t really have a bass player. I remember I was talking to Jarvis about it and I said “What about Steve Mackey?” We knew him from Sheffield, “He’s living down here, try and get in touch with Steve and see if he fancies doing it.”

So Jarvis did and Steve jumped at the chance and I think a few months later Steve was saying that he’d got a room going in his flat in South London, which was a squat. So I thought well everyone else is down there, I might as well move down for a bit. So I lived down there for a couple of years. ‘Legendary Girlfriend’ got a good write up in the NME and it was kind of the first uptick since ‘Little Girl’ really, which was a single of the week.

But the difference between this uptick and the previous one is that this one didn’t stop upticking. It did it very slowly. We were starting to get better write-ups and we started getting a bit more attention and we started to get little bit better gigs and that kind of thing. People started coming to see us a little bit more. So it was very gradual. That’s where the start of the slope began really, because we were in London. It did help to a certain extent, I don’t think it was the main thing, but it was like another brick in the wall that was in there to help build Pulp up. We finally had some solid foundations and bricks were slowly starting to be put into place. But as you know it still took a hell of a long time.

Is it right that you more consciously aimed to write pop songs in that period as opposed to many bands in what could be now seen as the indie genre as more shoe-gazey?

We were all quite dismissive of overly distorted music like your Jesus and Mary Chain’s and Ride’s and things like that. Like your shoe-gazey stuff, My Bloody Valentine, etc. As Jarvis would call it, Hoover music, it sounded like you had the Hoover on. And certainly everyone in the band really wasn’t into noisy music. We weren’t particularly into grunge or shoegazing, and we preferred things like Burt Bacharach and 60s singers. Your Lee Hazlewood’s etc. However when you try and write pop songs you can end up with something like a stupid nursery rhyme. In fact, just this afternoon I was driving the misses into town. We’re talking about pop songs. I was saying, it’s really hard to write a pop song that doesn’t sound stupid. And some rubbish we worked out and tried to do was just cheesy and horrible. But by doing that, some worthy items did come through.

But what made some of those singles that came out on the Gift label was that Jarvis’s lyrics tied to that sound made them left field.

He did some of that. I think there was a lyrical shift from the pre-me era, the Freaks era, to the Separations era. He started getting a bit more seedy and that kind of thing, and he did, I suppose, become a bit of a sex symbol, which we thought was utterly hilarious. You know, we’d see him in his Oxfam clothes and hair all over the place and he’d not washed for a few days. He was not a sex symbol, I can assure you, but the press seemed to take upon this. Maybe that was like a virtuous circle that if people think he was being a bit sexy, maybe that kind of brought that bit more into his lyric writing. But, when people say, Jarvis the sex symbol, we were like, crikey. That is a big leap of faith, that is.

His lyrics had an observational style, like a character study with tracks like ‘Razzmatazz’, where he’s talking about someone.

When you move to London, you do meet some characters. And certainly as we started getting around a bit, you did start to see them. Obviously Jarvis was at St Martin’s Art College, which was full of people dressed as Christmas trees and that kind of thing, so it was all a bit different. And what I found when I moved down to London is that you feel that connection to the place you’ve come from and you see it in a different light and it affects you in a different way. And so maybe you see the strange stuff of Sheffield through the prism of not being there as something maybe more worthy of talking about, perhaps.

Because you then know what makes Sheffield unique because you’re not there.

Definitely. You look back to it and you think about the characters perhaps you’re meeting in London and reflect them against perhaps the characters you knew from Sheffield. Often they can be very different. Going towards the character in ‘Common People’, the Greek girl feeling that people are slumming it a bit, hanging out with kids who’ve actually got no money, just because it’s just a bit daft. You did meet those kinds of people who didn’t have to live in a squat but thought, hey, I’m going to be edgy and live in a squat, but didn’t really have to.

So you had a series of singles that started getting to the lower echelons of the charts. There was ‘Lipgloss’, which got to 50 or something. But wasn’t the first big single ‘Do You Remember The First Time?’

‘Babies’ was the first one that got us on Top Of the Pops. For kids these days, they think Top of the Pops, what was that, some old thing? But when I was in my teenage years, Top Of The Pops was a big deal. If you were on Top of the Pops, you could officially call yourself a pop star. If you’re in a band and you haven’t been on Top of the Pops, you were a wannabe pop star. You can only say you were if you’d been on Top of the Pops. So once we’d been on that, we were so chuffed that we made it on Top of the Pops, it was unreal. Unfortunately, once you’ve been on a couple of times, you realise that it’s a very dull day and you don’t want to do it anymore [laughs]. So for me, ‘Babies’ was the big breakthrough record because we got on Top of the Pops.

But I was talking about the slope of stardom. For such a long time, it was going up almost an imperceptible slope. You didn’t really think you were getting it, but that slope was slowly getting steeper and steeper and steeper. You don’t notice it. ‘Do You Remember The First Time?’ it was one of those where we had a decent budget for a video. You knew that people were expecting it and waiting for it because ‘Lipgloss’ had been out, done well with ‘Babies’ etc.

Stuff got a better reception and you’re doing more press. And of course, coming out on Island Records, you can have a bigger push behind it. We had publicists, we had radio pluggers and all this kind of thing. Really good people who were like the blocks in a wall, putting all these people in place. So we’re at that stage where we had the utmost confidence that people were going to get to hear it. And we were confident it was good, they were going to like it. And they did and that was pleasing.

The drums propel ‘Do You Remember The First Time?’. You hear it and it grabs your attention and pushes you along.

I can’t remember the writing process of ‘Do You Remember The First Time?’. Maybe it was longer than perhaps other ones, because you remember the immediate ones. I remember trying to get my style of playing to sound like Ped Gill of Frankie Goes to Hollywood, the way he used to use his high hat pattern, the accents on that. I really wanted it to have a vibe of that. Whether I did or not, who knows? But then you learn that Trevor Horn programmed all the drums anyway, he never played a note on any of the records. So rather than saying Ped Gill, probably Trevor Horn would be more of a correct analogy to make.

Ultimately, about a year or so later, you went to work with Chris Thomas, who’s got a massive pedigree in the industry.

Absolutely. I think once we’d done the His and Hers album with Ed Buller. When it was time for the next record we knew hopefully, that it was going to be a step up, it was going to be seen and reviewed eagerly. So I think we thought, well, Ed did a good job, but perhaps it was maybe a little bit too reverb, a bit too echoey etc. So we thought, well, we’re going to have Island give us basically as much money as we want to record it, so we can get someone who’s going to really do an interesting job. I remember a few names being bandied around, as well as Mr Thomas. There was Jeff Lynne, he was talked about for a bit. Vince Clarke of Erasure, he was talked about. We’d done some tracks with Stephen Street, who did the Blur stuff. He was obviously the mid 90s go to young bloke, he was in the frame, there were quite a few. In the end we went with Chris Thomas because we looked at the songs he’d done in the past and we just thought he knew what he was doing. And a very interesting bloke. Looked a bit like Mick Fleetwood.

Big, big sound, though.

Big sound. Big studio, yeah, big sound. The kitchen sink is there on Different Class. There were times when you thought you’re going to be in a 24 track studio, sod that! Let’s go 48 track! Oh no, that’s not enough. I think we ended up with like 72 tracks on there, something absolutely crazy like that. But, everything goes on there. That’s one of the great things about going in the studio, is that when you’re writing and you’re rehearsing up the songs, all you hear is guitar, bass, drums, keyboards, mumbled singing, you never even hear any words. But then you go into the studio and you lay the basics down and then you start hearing the words. Then all the other stuff gets added that beefs the sound up. The little bits that folk think of and that all adds to it, you see the development of the overall sound and that’s the really exciting bit. And certainly hearing the words. We knew the song was called ‘Common People’, but you never heard any words because all you got was [mumbling] Jarvis working out his melody rather before thinking of the actual words. But then in the studio, you hear the words come out and you start thinking, yeah, this is getting really interesting.

One of my favourite bits about the recording of ‘Common People’ was doing some mixing or some overdubs and stuff like that. We were all sat in the studio, lolling around, reading the paper, being deeply bored. The doors were open, and someone was out in the corridor with a Hoover. Hoovering up. Mr Thomas took umbrage, and suddenly stormed out the studio shouting this thing, “We’re trying to make a fucking hit record here!” and slammed the door. We were all perked up from our newspapers going, “What was that?” And he sat back down, pressed play, and it sort of really hit home that, yeah, you were making a hit record. And it was kind of quite an amazing realisation that although the record wasn’t finished, it was going to be a hit record. That was quite an amazing moment, really.

‘Common People’, of all the songs on Different Class, is one that has such a driving sound. It’s not complex musically, but it kicks.

Well, that’s it. Because I would like to say one of my styles is not adhering to perfect time. Some would say that’s a flaw in a drummer. I would say it’s a requisite part, because it gives you the excitement of the track. We tried doing it when we recorded at a constant tempo. So we decided to start at the start tempo and keep that going throughout the song. And halfway through, everyone was falling asleep, it was so dull. So we thought, all right, well, that’s no good, so why don’t we try at the end tempo? And it was like, my god, this is starting so fast. We couldn’t handle it. So we thought, alright, that’s no good. We tried the middle tempo and it just didn’t have the drive, it didn’t have the excitement, didn’t have that feeling of almost like a runaway train, the feeling that the excitement builds and builds, and it comes to the crescendo. You had to use a click track in your headphones to record it so that all the electronics could be fixed onto it as well in the correct time. And so we ended up starting at my start tempo and mapped it out so that the beats per minute gradually got higher and higher throughout the song so it mapped exactly. I would play it without any click track in the headphones, how would I play it normally. And that’s how we ended up doing it, because it gave it its excitement, gave its rush. That’s how we had to do it.

It’s a contrast to popular music today. But when you look at ACDC and Phil Rudd, or John Bonham and Led Zeppelin, and you track the speed of the drums, it fluctuates. But that’s what gives it its soul.

I think it gives songs a sense of excitement, a sense of, this is something to get excited about. So I’d like to take the credit for all that. Thank you.

It was massively successful. Also such a contrast headlining Glastonbury when you were struggling to fill a pub five or six years before.

Absolutely. You’re right. The story of how we got Glastonbury is quite well known. But thank you, John Squire, for falling off your bike and busting your collarbone. I will forever be grateful for him doing that. We got a chance. It’s not every day you get a phone call from someone saying, “Yes, do you fancy headlining Glastonbury on Saturday night.” “Erm, yeah, okay. Yeah, we’ll do that”. So we went and did it. And you’ve never seen five people in a room so shit scared of something. The ten minutes before were due on stage on that June night, all just sat there looking at each other. Everyone was literally quaking, as I’m sure you could imagine, because we didn’t know whether this audience that had paid to see the Stone Roses were going to bottle us off or what. We just didn’t know. And it seems crazy now.

We played six new songs or something in that set that we were mid recording for Different Class. So bizarre. Then we finished with ‘Common People’, and you look up at the end and how every member of the audience seemed to be singing at the top of their voice, and all you could hear was the crowd singing even above your own playing. So it was pretty amazing.

Strange in a way, because you didn’t change your sound to conform to what was going on. It was actually the people who caught up with you.

Yeah, things change, don’t they? People are fickle buggers. Everybody was into plaid shirts and Nirvana a couple of years before, and then all of a sudden, everyone’s wearing daft ties and sort of corduroy a couple of years later. Fashion changes. I suppose it moved in our direction and we were the beneficiaries of such. People like different things. People like things to be new. You’ve got this lanky get arsing around on stage. People think that’s different. That’s interesting. We’ll have a bit of that.

Our lowest attended gig, which I think was two paying customers at a club called the 20th Century Club in Derby. That would have only been about five years previously, if that. Maybe even less. To play in front of about 100,000 people. It’s quite a move. And even those two people at the 20th Century Club, they’d gone in on the wrong day. A car of lads came down from Sheffield to watch, so there were more people they didn’t pay to get in of course. There were about six people in the audience, only two of which had actually paid to go in and they got in on the wrong day. And these two girls, and I hope they remember that day, because even though we could have just gone sod it, we’ll go home. We still played them a gig and hopefully they remembered it and enjoyed it. There you go. Two people.

After Different Class, you had the task of trying to follow it up. It must have been quite a period where it’s like well, where’d you go after such success.

Very much so. We had a few conversations of, like, we don’t want to churn out versions of ‘Common People’ or trying to get back to… Pulp has always really wanted to develop and try different things out. There was never sort of thing, oh, we’re going, we now going to make an album that’s dark and confusing to our fans. Maybe a bit dour. It’s kind of what comes out, really. But I know that we didn’t really want to just trot out Different Class two. It was very hard to make, This Is Hardcore. Very hard indeed. It took a long, long time. I think that maybe that’s a function of having finally found success, is that you’ve got a focus before that of where you are going when you’ve got there, where do you go next? And it’s difficult to do, basically. So it took a hell of a long time and it was tough. But the track, ‘This Is Hardcore’. That took absolutely forever to get right. But you still listen to that now and you still get goosebumps. It’s an amazing bit of work.

There’s a sample that’s throughout ‘This Is Hardcore’. Was it hard to drum to it?

It was a bit, because it kind of gave you a bit of a beat as well. So when you’re using things like drum machinery type stuff, like, you got a little bit of a beat in that. And some of the older stuff with the Yamaha Portasound had beats. You’re either gonna go between what the machine’s doing, or sort of just back up what the machine is doing and then you’ve got to try and keep in time and all that sort of thing. Obviously with ‘This is Hardcore’, being quite a long piece. We’re sort of trying to weld various other ideas into it as well to make it interesting. Because obviously if you’ve got one sample going all the way through, it can get a little bit tiresome. So you’re trying to bring in other elements in with it to keep the interest going. It took a long time to get the right elements working together, I suppose. Yeah, it just takes a long time.

And in those sessions is a track that I think eventually came out as a B side, ‘Tomorrow Never Lies’. But that was potentially a Bond theme, something you were asked to try out for.

Yeah, we were recording This Is Hardcore at Olympic Studios in Barnes, and I think we got a message through from the management saying oh yeah, the Bond people. It was probably a fax in those days, saying they’d like Pulp to submit a song for the next Bond film, Tomorrow Never Dies. We were all massive Bond fans and love Bond music. We’ve got to go for this, we’ve got to try. And so this note came on something like a Wednesday, and it said, oh yeah, by the way, could we have it by Friday?

It was so typical of film people that they think you’ve just got something off the shelf you can just send in, oh yeah, we’ve always got a few Bond tracks just sat waiting for the call. So luckily we were in the recording studio at the time. So it was a case of, right, okay, what we got left over from the writing sessions that we could perhaps utilise for this. It’s kind of like in two bits, the song. I’ve not heard it for ages, to be honest. I think we had the first bit that we’d worked out and then I suggested, why don’t we try that bit? Stick it on either the middle or the end or something. And it was quite exciting because we worked it out one morning, sticking these two bits together in the studio, and then we literally recorded it in the afternoon, mixed it in the evening and sent it off on the Friday morning. And then in typical film circles, you just hear that Sheryl Crow got it and you think, well, yeah, why did we go to all that bloody effort? Then we said, well, we’re not going to waste it. It was quite an exciting little thing. So we put it out as not ‘Tomorrow Never Dies’ but ‘Tomorrow Never Lies’.

So for the album that became We Love Life, you started to record with Chris Thomas again but things were just not gelling?

It was even more difficult than Hardcore, really, because we had a bit of a break and then we were slowly putting songs together and yeah, it was difficult. We started doing some bits with Chris Thomas, but we worked on the songs to more of a finished degree and then started coming in with half thought ideas and trying to do it in the studio, which for me isn’t really the way things should be done. I think you’ve got to come in with a hundred, or say, 90% finished items but we weren’t so much. So we just thought we were just going to sort of get the same as what we’d had before. We thought it was time to try something else out. So we tried with various folks, there’s a chat with glasses, but what was his name? Can’t remember. Yeah, we basically recorded the album twice, recorded it once and just thought it wasn’t it wasn’t interesting enough.

It wasn’t sonically doing what we wanted it to do so we started casting around and seeing if there’d be someone else. I can’t remember who else had been in the frame but then you get another one of these life changing phone calls of Geoff Travis saying “I just had a call from Scott Walker’s manager. Yeah, Scott’s really into doing more of a pop than an experimental album. What do you think if Scott Walker did it?” Obviously me and Jarvis were huge Scott Walker fans. It was kind of like, this is an opportunity not to be missed, to work with someone like Scott Walker. So off we toddled back into the studio with Scott Walker to do it. That was quite amazing, really, working with the great man. Sadly Gone.

I don’t think in terms of sales it was a massive seller, but actually it was one of your best albums. It’s a fine record.

Yeah, you’ve certainly got a breadth of stuff on there and it certainly doesn’t sound like we’re trying to re-record stuff we’ve done before or try to sound like stuff before. It is different. A bit more sort of hippie-ish kind of album, I suppose, but you just go try things. But it was again, another one that was really hard to do and I think by the end of that we realised that maybe our time was drawing to a period where having a rest was maybe the best option. Pulp never really stops. It just sometimes gets shoved under the bed for a few years. So after we’d done the We Love Life tour and again finished it back in Sheffield, it seemed like a natural way to draw the veil for a bit and to move on and go and a rest. So we did basically.

‘Sunrise’ was released as a joint A-side, but it should have been a big hit.

Yeah, it’s kind of like a bit of a magnum opus. Great one to play that one live as well. These days, I suppose it started coming in the 2000s, songs of length that aren’t immediately there, do they get chosen to play on the radio? Were Pulp seen as a bit of last year’s model type thing? It’s just the way the spotlight of interest moves around. Once you move out of the spotlight it is difficult to get back in there. I think we left a solid body of work.

There’s one track that I think originates from the We Love Live sessions that was released was ‘After You’. You re-recorded that song for some of your live shows.

I’m not sure how that recording came about. I think we’d been rehearsing for some shows, and we’d start messing around with that. Jarvis thought it would be interesting to record it. Maybe he was sort of testing the water, to see whether we should think about doing a new record. We didn’t in the end, but all the same, ‘After You’ was quite interesting. Who was the guy that did it, you’ll probably be able to tell me. James.

Oh, Murphy.

James Murphy. He was a nice lad. It shows my age, I can’t remember these young people’s names!

Since that period, you’ve played some shows with Pulp, but in more recent years, you have been much more active with the Everly Pregnant Brothers. How did you get to link up with Pete McKee and the guys?

I knew Pete McKee a little bit through Richard Hawley, and I hadn’t really seen the Everly Pregnant Brothers at all. And Pete just said one day in the pub, “Do you fancy joining us for a couple of songs at our show coming up? And I said, “Yeah, of course.” I like to think that if you don’t do anything, nothing happens. So I said, yeah, “I’ll come play on a couple of songs. Me and Johnny on the double bass were asked at the same time, so we had a good time rehearsing and playing on a couple of songs.

It was a two night gig, so I think on the second night we played a couple of other songs as well. They enjoyed the contributions that we made, so they said, “You keep playing with us and that”. Everyone in the band is a nice person and we all have a great time doing it. So it’s not difficult to say yes. Being in a band should be good fun. And with the Everlys, it is great fun. There’s no great pressure. Live gigs are pretty special because of the crowd participation. A band should be like being in your own gang. A little gang of over 50s who have got more medical complaints than Holby City.

Do you think therefore the track ‘Prescription Drugs’ from the latest Everly Pregnant Brothers album would be appropriate to finish on then?

Very much so, yeah. [laughs] I’ve got a bad knee. One of the lads has just had a back operation. Pete had a liver transplant and has just had another operation. Big Sean is constantly having problems. So we’re a right bunch of old crocs!

For those that don’t know, the Everly Pregnant Brothers do their own versions, often on the ukulele of very famous tracks. Is it Pete who kind of gets…

That’s right, with often liberal amounts of swearing in there. It’s probably very litigious copyright wise, but hey, we’re just having a bit of fun. There’s no high art in there. It’s just a bit of fun. Get people to have a few pints, sing top of the voices and enjoy it. As long as it stays fun, we’ll do it.

Well, all the best with those shows and maybe things will come around with Pulp one more time again. That’d be nice.

Never say never.