With accolades from industry insiders and a coveted spot on the cover of Billboard magazine, Micky Greaney’s music career seemed poised for major success. However, as he reflects, his story takes a unique turn marked by pivotal decisions and unwavering conviction.

In his conversation with Jason Barnard, Micky delves into the challenges he faced when transitioning from local acclaim to the prospect of securing a record deal. Recounting a momentous offer from Parlophone Records, he shares his decision to turn down a quarter-million-pound deal, opting instead to stay true to his band’s identity.

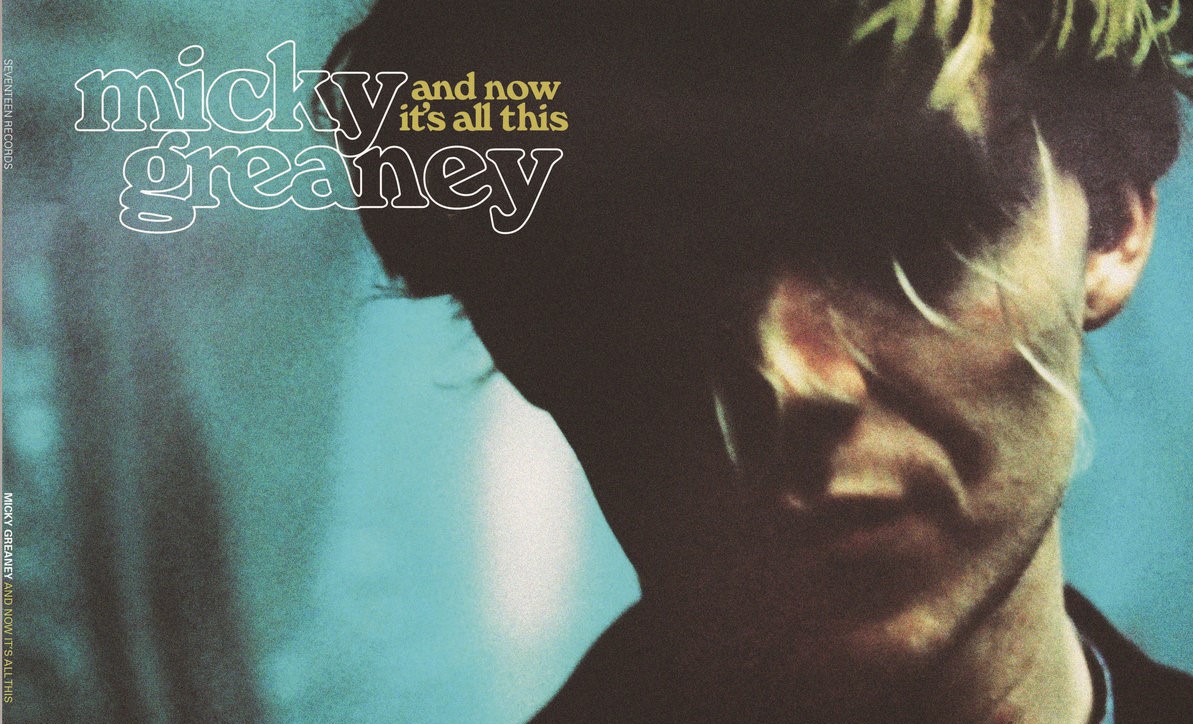

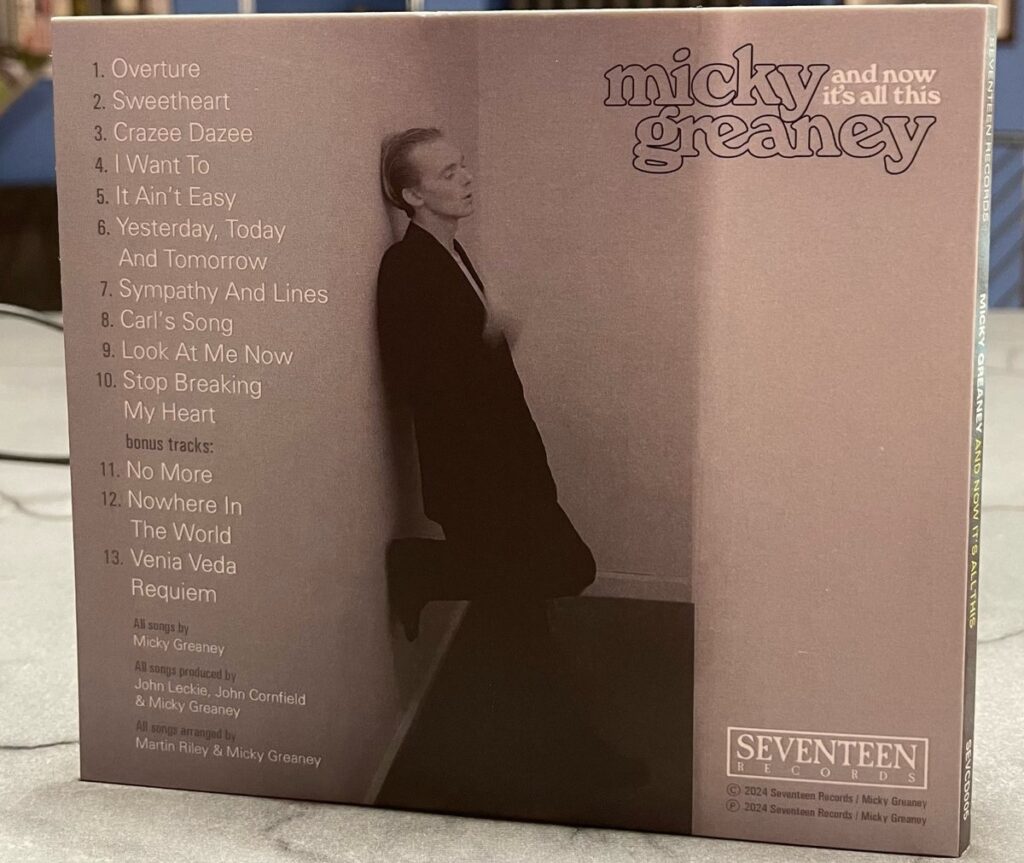

But now after decades of anticipation, Micky Greaney’s long-awaited album, ‘And Now It’s All This‘, recorded in the mid-90s, sees the light of day. This once lost record was partly recorded at Abbey Road with producer John Leckie, showcasing Micky’s artistry and collaborative brilliance. Through this interview we explore his highs and lows, and he offers poignant insights into the lessons learned along the way. For him, every choice made has been guided by a steadfast commitment to family above all else.

What led you to revisit and release the songs recorded at Abbey Road back in the mid-90s to finally release your second album, ‘And Now It’s All This’?

Thank you very much for asking me these questions. We were looking at re-releasing ‘Little Symphony’ for ages, but the guy that paid for it, he wasn’t really up for that. I went out to Prague. I had an interesting recording experience with David J from Bauhaus. We’re still great friends but we weren’t vibing off each other.

But I stuck it out and recorded a few songs with the Czech Philharmonic and Symphony orchestras, it was a combination of the two. Then I got home and then eventually got in touch with John Leckie and sent him the tracks that I’d done in Prague and he was really furious with me. He was like “We’ve already done that. We’ve already done ‘Sweetheart’. Why the hell are you recording it with an orchestra? We did a great version of it already. Don’t you remember?” He was kind of angry with me because he’s a serious guy. It was weird and we hadn’t spoken for like years. He knew all the tracks, remembered all the songs, word for word, line by line and each individual recording.

All the original masters were lost. So he sent us a bunch of C-90 cassettes that he’d done his own little mixes on. He sent those over to John Rivers at Woodbine Studios in Leamington who put his magic on it. Also John Purcell and Chris Coleman at Seventeen Records who are putting it out now. Without all these people none of this would have happened.

What was it like working with producer John Leckie and how do you think his influence shaped the music?

Well, to get to work with him, that’s the first bit. I’d written this tune ‘Sweetheart’ about my mother and also about the mother of my eldest boy. We did this thing at Pebble Mill and it sounded smashing, really lovely everything right about it.

I met Nick Moore one night after some shows at the Water Rats and I said “I know I’m really good but how do I do it?” He just demystified the whole thing and he said “Who do you like? What’s your favourite album at the moment?”. I said ‘The Bends’ and they said well “You’ll never guess who I work with, John Leckie”.

I remember later, sitting with the band all sat around on a cricket pitch in a circle and saying I’m going to London and I am going to get us John Leckie. They literally thought I was a nut job. But I had an in to drop the tape off. I met Safta Jaffery and he went “No, John’s not gonna like this. He’s very, very busy” because he didn’t work for unsigned artists. Then by the time me and Lorna drove back from London to Birmingham, the phone rang. It was Safta and apparently, I was the next best thing in the world. Then a lot of people were sniffing around. A lot of major labels and stuff and then he just said “Right okay, I’ll get you in Abbey Road with John Leckie before Christmas. I’ll get Parlophone to pay for it.”

Working with John was so much fun because he didn’t take any shit. He was the same as me, if you don’t work nothing’s gonna happen. So all those takes on this album, they’re all just they are all basically live. You’d touch up backing vocals and he’d sit me down at the mixing desk at Abbey Road and go “Right this is how the mixing desk works. It’s really simple. Trust me to go off to Sawmills and sort out the tracks.” The thing I loved most about John was he’d come down to see Aston Villa with me. He’d come around to my mum and dad’s house and watch a bit of telly. We go to the match then go around after. It’d be like a ton of sandwiches and loads of cups of tea and having the crack with my dad. My dad was always taking the piss out of him and he knew it, he was just great.

What makes him a great producer is that he’s very straightforward. You’ve got to be on your game otherwise he’s gonna be on your tail. He was just so down to earth. His dad was a proper barrow boy. He’d written a letter to Abbey Road, that’s how we got his job. Everyone else was getting apprenticeships in factories.

John said his favourite two bands he’d ever worked with were The Fall and the Mickey Greaney band. For that I’ll always be eternally grateful. I’m very grateful to John for keeping a bunch of stuff that I didn’t have and sending it over and making this all happen. It was a very special couple of days. I think everyone did great.

Can you share any memorable moments from the recording sessions at Abbey Road and Sawmills Studios?

Walking into Abbey Road was probably up there with any experience in my whole life. It was a great couple of days and it wasn’t just me that was having a great couple of days, it was my whole band. Some of them were really young and had just come from, or were still in the Birmingham Conservatoire. We were pretty hot at the time.

We only had two days at Abbey Road and I overslept. I didn’t get there till like 1 o’clock in the afternoon, I was meant to be there at 9 in the morning. Also down in Sawmills, we’d go to the local pub and have a big old sing song. There was a kind of river thing outside of Sawmills, but it turned into mud. So me and Richard, the drummer, tried to have a race over that, up the hill, he absolutely mashed me up, man!

I was writing good songs at the time, that kind of eases the process along there a little bit. But I knew I had to really impress some proper people, which I did. I remember the amazement in people’s eyes hearing the songs.

The Enigma Quartet played a significant role, typified by ‘Sweetheart’. What led you to collaborate with them?

‘Sweetheart’ is a fantastic example. I had this little tune in my head, a kind of gothic thing, baroque with a bit of an Irish lilt too.

I was working with loads of people at the Conservatoire, 30 odd people. I met them when they were first year graduates, but they were tight as friends. They came as one. Having worked with them when they were first years, they weren’t quite there at the time. So for me it’s a little bit like being a football manager, you’d send people out on loan, but I liked about The Enigmas that they came as one.

I could bring a song to them like ‘Sweetheart’ and they’d help arrange it, even though Martin Riley was the arranger. We could take it to Martin and go, “What do you think of this?” It was kind of done really. The thing I like most about them is that, our guitarist Carl Vincent, he lived in a nurses home and there was like a big playing field outside of it. After rehearsal, they were well up for a game of football or rounders or just having the crack really. Like going back to John Leckie, it’s all about personalities. They just brought so much fun to it.

In one way I think I helped all their careers. They’ve said that to me. Some of them now work with Richard Hawley and they play all around the world. They do stuff I’ve never done and I think that’s fantastic. Playing at Abbey Road and Sawmills when you’re still at college must have been great for their confidence. They’ve done amazingly well since then.

But a very important point is that they kept it light as well. You need that yin and yang. I was always very conscious in making that band that it should be like half and half, half classical people and half rock and rollers. We went through three arrangers and about six quartets. We had 15 people in the band at one time, three drummers, but it was just so amazingly simple to me. To just walk in there and there’s all these musicians and take your pick.

We had a great little local venue called Ronnie Scott’s in Birmingham, we had a place to play and the stage was big enough and sound was okay. So you could develop people But they really learned their craft and hopefully I was part of it.

‘Look At Me Now’ is one of the tracks that has been released in advance of the LP, what inspired this song?

It was Lionel Bart who counterbalanced voices. I was always a big fan. We share a birthday with Andrew Lloyd Webber who’s a genius.

A lot of people had done a counterpoint melody and I was at the start of a relationship with Lorna, who is the mother of my eldest child Theo. At the time I really liked her. I was thinking whether she liked me as much as I liked her. I think she was still soft on someone else and it wasn’t getting to the place where I wanted it to be. I wrote it down all at once, it all came to me, both parts. I had a tape recorder where you could tape something and tape the other bit. I think Lorna was working that night, I thought, “I’ll surprise her, when she comes home she’s really gonna love this song” but I didn’t play it to her. In fact I didn’t play it to anyone for five years because I thought I’d kind of frighten her away, in a way.

Then one day I found the tape, I played it to Carl who was the heartbeat of the band really. and I said, “What do you think of this?” He went, “That’s brilliant” and I was like, “Really?” I might have played it to her once but Lorna was like a tough girl, I thought I can’t get too soft, this is too much. I think now she likes it but at the time I was a bit shy about it. So literally five years and then all this John Leckie stuff started happening.

So I thought I’d write a song and then write another bit of a song and make it bigger and bigger. So I wrote one part and then recorded it and then wrote the other part. It seemed really simple to me. But it’s really hard to sing a song with two vocals to someone at the same time. So that’s why I didn’t really play it.

The great thing about those girls in The Enigma Quartet, they jump in a car with you, do a little show with you and if you were having a game of football after the rehearsal. They get stuck in man! So when I formed another band about 12 years ago, I wanted strings involved in that. The whole point of that band was to do a minimal version of the original 12 piece band. So it was a nice compact band, but just a violin and a cello player. So that relationship with classical players, it’s really important to me.

The closing track, “Venia Veda Requiem” is quite ambitious. What led you to writing this epic piece, and how does it tie into the overall narrative of the album?

In a sense the band had moved on a little bit. We had a different drummer, we were drumming with Fuzz Townshend. We’d played loads more gigs. But my very first drummer and my best friend forever, unfortunately, things didn’t work out well for him and he committed suicide.

He walked off the edge of a flat, I’d seen him the night before, and I felt like I let him down. He was asking me to help him, but I was a little bit afraid. I’d never seen that before I was a kid. I was only 19 and he had violent intentions towards himself and I thought “Man, that’s not for me”. On his way he found my mum and he said “Is Mick there?” and I wasn’t. He said, “Can you tell him I called.” He was dead within an hour of that.

But the next morning I found out. I was working for roofers, they picked me up and they had the newspaper. They said, “Mick, we’ve got some bad news for you. You need to read this.” It was only a little column. It said Steve Johnson from Trinity Road had walked off the end of his girlfriend’s block of flats. So two other guys out of my original band made it to Abbey Road, but Steve didn’t.

I got into Nusrat and Jeff Buckley at the time. I wrote this pigeon latin thing because I didn’t want everyone in the world to know I was apologising. So all that, ‘”Vin-e-a dana”, is pigeon latin, “No one understands you” is me saying sorry to him, I let you down. Then it goes into this sort of thing where I’m talking to him, “You really should remember, you should recall” about us growing up in Witton Road and how great it was growing around there. He was the best fun, we were so close. We literally lost our virginity together, waited to do it. So it’s my message to him, beyond the grave kind of thing.

The song recalls all the spices and the Indian shops and stuff like that, silk and saris, and then the melody takes you into the garden. Then it goes into this thing where he lost his life because he lost love in a way and he couldn’t cope with it. So I explore in the song, the idea that he’s in heaven. So that’s him finding his love. Now he’s in nirvana. But it’s basically about Witton Road and my dear, best friend who died. So, it was a nice musical little thing to do with the band.

What do you hope listeners take away from “And Now It’s All This” compared to your debut album?

I hope they’d like them both. People really seem to like ‘Little Symphonies’, which is absolutely great. A lot happened out of that and a lot of people have been waiting to get their hands on these recordings. The reaction has been really amazing. So I hope they enjoy them both really. I think they work well together. I’m thinking there’s a couple more albums left in me.

How do you feel about the reception it has received?

Ridiculous, I’m being compared to all sorts of people and like it’s a mystical, lost album. The Holy Grail and stuff, that’s a load of nonsense. That is brilliant and I am not trying to put any of that down. But I have got a lovely opportunity now, haven’t I? To have this kind of reaction to something that I always knew was good is amazing, because I knew it was amazing. That’s why I stuck by it in the first place.

I’m 57 now and I was kind of 30 when I did it. It’s great that some people that haven’t heard it are hearing it for the first time.

Your musical journey began with bands like The French Way and The Girls in the 1980s. What do you remember from that period and did these early experiences shape your approach to songwriting and performing?

The French Way? Initially, I was belting out some lovely tunes, and for our first gig, we found ourselves in an attic filled with Mormons and Rastas. However, despite thinking we were onto something special, with people flocking to Peacocks and appreciating our music, reality hit during the Battle of the Bands.

There was another band, The Rag Dolls, which Slim was a part of, and they caught my attention during the same competition. They blew my mind, especially Dave Kusworth and the entire band’s performance. Despite their talent, I think they only came second. Meeting Slim for the first time, I sensed a connection as we shared a moment over a pack of Woodbines.

While others were busy with Peel sessions, Slim and I aspired to be pop stars like Bros. We brainstormed names for our band, inspired by The Rolling Stones, eventually settling on The Girls. Our rehearsals often resembled impromptu dance sessions in front of a mirror. I had a mirror over my bed in my purple love parlour in Aston! [laughs]

We recruited Bobby Bird, Steve Bass, and Fuzz Townshend, and did some exciting gigs but we were sort of groomed for being a boy band. We had a mainly female audience which was great because that’s why many lads pick up guitars.

Me and Slim don’t talk that much these days but I had the greatest time with him. The thing about being in The French Way was I always wanted to learn. I thought, right, I better write better songs because my songs were about being on the bus and meeting a girl. The Rag Dolls would get on stage and it was like they were Birmingham’s Rolling Stones. The rafters would go off. I thought. “Why can they do that?”. Then our bass player joined The Rag Dolls later on. There was a lovely crossover.

I just said to Slim, “Look, we need to be famous, man. Famous pop stars. Everyone else is going down to Maida Vale and doing all their recording sessions and doing their gigs in Camden. Come on, kid, we can do this, right?” Next thing we know, we’re doing a standby for Wogan. We were dressed in the most amazing suits, lady suits from French Connection with 32-inch flares. It was very, very good.

The Lilac Time got it ahead of us. The lovely connection with me and Stephen Duffy is that we don’t really know each other. He recorded with Bob Lamb and then John Leckie. And he was the other guy who did the audition at Wogan and he got it. And he went straight into the top 10 of the charts because he got that thing. If we’d have got that, we’d have been in top 10 of the charts. Dave Kusworth gave me his copy of The Lilac Time – The Lilac Time. It was signed by Stephen Duffy, and he went, “You’ve got to listen to this”.

At that time, I was a little kid. That’s what I loved about the French Way and The Girls. It’s like you have a bag of flour, bucket of water and some stencils and you got some posters. We were keen, we were young, and we were pretty good. The French Way was a great little band, but I think The Girls really had some amazing songs. But The Girls were amazing.

‘Little Symphonies for the Kids’ was your debut album released in 1994. Can you tell us about the inspiration behind the title and the creative process behind the album?

The title is related to Phil Spector, but it was meant to be Micky Greaney – Micky Greaney. Hugh from Mighty Mighty, he wanted his brand so large on the label that it said ‘Little Symphonies For The Kids’. ‘Little Symphonies For The Kids’ was his label, but then people just started calling the album after it.

My girl was gone and I thought, “I’ve got to get her back”. So I drank myself into oblivion and my cousin Johnny X, he came over from Ireland and I went, “You can’t be here”, I’m coming off the drink and then I didn’t drink for 10 years and that really helped.

Like I said before, there was a fab new place called Ronnie Scott’s in Birmingham. All sorts of famous types of hanging out there. I thought, oh, well, I’d be good there and I’ll get my girl back.

So with ‘Little Symphonies’ I was working again, on that lineage of Stephen Duffy – Bob Lamb, he was one of the great producers of all time. It just gave that thing a special something really. There’s footage of both albums. We were younger and we just laughed our heads off. There was some of that energy left in little symphonies. It was a really fun session and like I kind of said to Carl and Richard “You’re my boys, man, we’re going to do something. Then we got on with it.” I think they were quite fascinated in the sense of, we need a string quartet on this tonight. So that’s when all that getting into the Birmingham conservatoire started happening.

With high praise from industry insiders and even landing on the cover of Billboard magazine, it seemed like major success was on the horizon. What were some of the challenges you faced in transitioning from local acclaim to securing a record deal?

I had one of the most amazing record deals ever. We’d been at Abbey Road the week before Christmas. The phone rang, it’s Boxing Day and it’s Safta Jaffery. My mum and dad’s house at that time cost about 20 grand. Safta said to me, “Parlophone wants to sign you for a quarter of a million pounds. They think you’re special.” It was all in the singular. I went, “Right, they want to sign me for a quarter of a million pounds.” Lorna, she could hear me on the phone. I said “What about the band?”, he said, really “They only want you”. They’d let some of the lads play on it but if we’re doing strings they’d want London or BBC Philharmonic, something like that.

I thought we were a good band and so it took me about two minutes. I just said “I’m not interested.” He said “Mick, are you mad?” I said “Yeah, probably am, you know what I mean but nah, man. We’re a good band, they should sign us as we are.” I think they were a little bit troubled about the cumbersome nature of the band.

So I decided to blast on with the band. Mike Salt from Epic, he was offering me like 28 points which was unheard of. But all of these deals couldn’t be paid back until the end of the contract. The contract was five years and that’s when you started making money. Then I just thought that I’d prefer not to do it, I believed in my band so after that we had some great times.

We played some festivals and instead of doing the odd night at Ronnie Scott’s Birmingham we did a week at Ronnie Scott’s. Then we did a week at Ronnie Scott’s London and my dad had some really proud nights and stuff like that. To give all those people all those lovely memories. Jason, you see that’s important. But I knew the goose was cooked. I knew it wasn’t going to happen. I knew the ship was sailed and then that got to me. It got me ill, that’s why I want to be careful this time around with all of this going on.

It was very nice to get Billboard magazine. I spoke to Safta who told me I was on the front cover. I think what’s important is to talk honestly. I think I didn’t notice that mostly what I was doing was conveying very emotional messages to people.

Looking back, what lessons did you learn from the ups and downs of your music career?

What did I learn? I don’t know. Strangely, every time I turned something down in my life, I wound up happier. I’ve had a lot of choices. I could have gone away to different places. But I learned that the most important thing to me is my children, absolutely bar nothing. So I don’t regret any of it.

If I’d have signed to Parlophone Records, the chances of me and Lorna keeping it together and stuff like that. A quarter of a million in the 90s, it’s a lot but I was saying to mam, “Well, we ain’t going to see none of it.” Every step of my life, musically, is connected to my children, you see. So if I hadn’t made certain choices in my life, I wouldn’t have these five amazing people.

I met so many beautiful people on the way. George Martin was listening to my demo tapes when I was 17 and gave me an opinion. But I don’t like taking it all that much seriously. I’m old now.

What’s next after the release of ‘And Now It’s All This’? Do you have any future projects in the works?

The answer to that is yes. I’m booking the studio back out in Prague. There’s a great place, Barrandov Studios, with a great guy called Karel Holas. It’s an old radio station. So that’s where we’re going. We’ve David from Bauhaus helping and my good friend, Marc Warren, who paid for the whole thing. He played Van der Valk.

I think some of my finest songs have never been recorded and they are a lot of people’s favourites. I’ve got tunes like ‘Michael Collins’ and ‘Out in the Morning’. So there are another couple of albums and then I might go fishing afterwards . My children are very musically talented, so I’d like to have a little family band with them and be excited about that.

Overall, I can be hard to handle sometimes. I think getting older and this happening now is very good for me. If it all kicked off earlier, I don’t think I’d be doing this interview. But now all my seeds have fallen, all my leaves are grown, and all of my kids. It’s great for them. So let’s see what happens. Jason, thank you so much for your support, I really appreciate it.

Further information

Micky Greaney ‘And Now It’s All This’ (Seventeen Records) is released on vinyl, CD and download on April 29, 2024 and is available for pre-order: mickygreaney.bandcamp.com

Beautiful interview. Never say it’s over. It’s never roo late when something is special and brilliant!