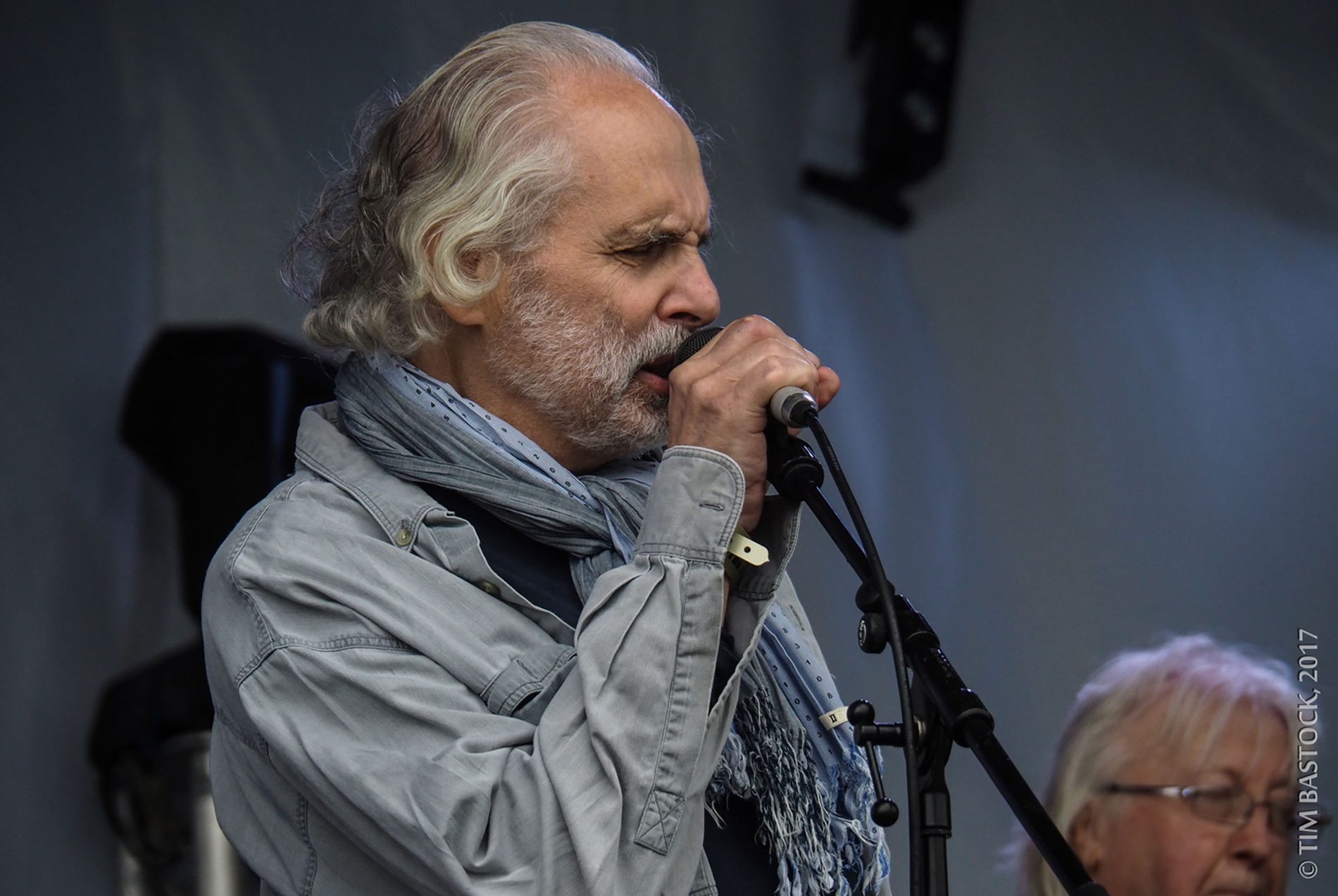

Pete Brown, lyricist for Cream, talks about his songwriting partnership with Jack Bruce, the Cream Acoustic Project and solo journey. [This is a transcript of his Strange Brew Podcast audio interview with Jason Barnard.]

It’s great to start with ‘I Feel Free’ because over time it has become an anthem and embodied the spirit of the 60s. Is that something that resonates with you and is that something that you were trying to capture at the time with the lyrics?

Well, I suppose it’s mildly psychedelic or maybe mildly pre-psychedelic but it was the first proper hit that we had. A genuine organic hit rather than the ‘Wrapping Paper’ which was bought into the charts, I ignominiously say. Wasn’t my fault. It’s also the only kind of song which I would think I would categorize as almost like a pop song because we didn’t do anything remotely like that after it, even though we had other hits. I mean ‘White Room’ certainly wasn’t a pop song and ‘Sunshine’ was a very bluesy type of thing. But the good thing about ‘I Feel Free’ really is that you’ve got a very interesting combination of elements which is a very hard driving rhythm section and then, on top of that, you’ve got this very very legato vocal and that’s a really great contrast. The only person previously to that that had done something like that was probably Brian Wilson. He did a couple of things like that with very hard driving rhythm but this was very special really. It’s a very special song. Very happy about it and of course it’s now in a bank commercial at the moment. Do you know about that?

No.

It was a UK one. Yeah. The Starling Bank. Rather kind of tame name for a rapacious bank. I think it’s a new bank and they’ve bought it for a year which is good news for the finances.

So, how did the songwriting work with Jack Bruce? Was it that he worked the melody around your lyrics or did you have a role? Did it vary?

Yes. It varied quite a lot although, because of the nature of the Cream situation, which was the fact that they were on the road nearly all the time because they were a cash cow for the management, then we didn’t get very much time to work on stuff and so some of it might have turned out quite different if we’d have had more time. Anyway, no, we did it. ‘I Feel Free’, certainly the music for that was written first and then I just kind of found the right words for that particular one but we did it all ways round later on.

And so, before the Cream years you were performing live as a poet and I understand it was Ginger (Baker) and Jack that actually saw you at one of those gigs where you were doing poetry.

Well, not exactly. I was a huge jazz fan and I was always down the jazz clubs listening to what was going on and I liked some of the older guys that were from the first generation of modern jazz and bebop and stuff like that but also mixed in there was this next generation which was Jack and Ginger and people like that and they were very, very exciting musicians to listen to anyway. When we started doing the poetry thing then Dick Heckstall-Smith, the great saxophone player, used to come and play with us on the jazz and poetry things and that was the connection really. That’s how I met Jack and Ginger through Dick and we got on very well, me and Dick. We were very good friends. We even lived in the same place together for a while and I do miss him very badly, actually. He was one of my best friends and of course later on I worked with him with Colosseum. In fact I’m still working with Colosseum, but that’s another story. Anyway Jack and Ginger… Ginger had heard me doing stuff. In fact he actually played on one of the jazz and poetry concerts. And Jack – there was a guy called John Mumford, a very, very fine musician trombonist who was a friend of mine and he was sharing a flat with Jack and that’s how I really met Jack. Went around, was sociable. And then when Cream formed, after being in the Graham Bond Organization, of course, which was to my mind the greatest British band – that was Dick, Jack, Ginger and Graham with occasional bursts of John McLaughlin. Then, after being in that, that’s when Cream began to sort of shape up and they knew that I could write. So Ginger phoned me up and said they were around the corner in the studio from where I lived and they said ’ere. You want to come around and write some words for this? and so I popped around to the studio and, lo and behold, there was ‘Wrapping Paper’ so that was how it started. And then it became obvious that Jack and I had a tremendous chemistry, that we had the same sense of humour. We had the same socialist outlooks and we liked a lot of the same music. You know we liked Charlie Mingus and we liked Duke Ellington and we liked (John) Coltrane and everybody and we would listen to stuff together quite a lot and there was that just kind of chemistry which I’ve always had with people from Scotland, in particular, or Celtic people generally. I’m actually married to one. I’m married to a Scot. She’s very Scottish in some ways. So there was this chemistry and that’s what sustained us, really. That was what was really happening and also we could work very fast. I could work fast, because we had to. And Jack could work very fast anyway because he’s very, very versatile. So we managed to get quite a lot done in very short spaces of time.

And the great thing about Cream at the time is that musically they were constantly evolving. The way that you were able to add lyrics worked remarkably well with the changing sound of the band. By the time you get to the Disraeli Gears and ‘Sunshine Of Your Love’ the sound had progressed even more.

That’s because they had a great producer by that time. That was another thing, of course, but on the other hand, yeah, we were well into it by then as a kind of a partnership really so we could do things relatively at the drop of a hat.

Yeah, and that song in particular. It’s just a such a great combination of the riff and as well as kind of that opening line ‘It’s getting near dawn’. So evocative.

Well that was the truth you see. We were working all night and then Jack picked up his double bass, which he was still playing at that time a bit, and he said ‘Well, what about this then?’ and played the riff and it was like five o’clock in the morning, it was in the summer and I looked out and it was getting near dawn so I wrote it down. Funnily enough, years and years later, when I started singing the song myself, I realized what it was about. I wasn’t quite sure what it was about but then actually what it’s really about is like a kind of musician or somebody doing a gig or doing work of some kind and then being on the way back home and hoping that his wife or girlfriend would be waiting for him and so something nice would happen after a lot of hard work. So that’s what it was really about.

And it’s interesting that some of the songs that we’ve been talking about seem to come very quickly and on the spur of a moment. But is it true that the ‘White Room’ was a much longer poem that you’d been working on?

Yes. It was an eight-page poem and luckily, one of my bits of education, was that I went to a journalism college for a while which I didn’t graduate from but at the journalism college I learned the art of precis which was how to cut things down and find the essential stuff in there and get rid of the unnecessary ornaments. Because there was very little time, as I said, for working with Cream, then all the ideas were considered. Jack had already written most of the music for ‘White Room’ and we tried a few ideas, a few lyrical ideas, that didn’t work and then I suddenly thought of this poem which was called ‘White Room’ anyway and I thought, well, if I precis this down to a page then maybe that could work and that’s what did work.

One of the great things is the references. You can listen back and get various meanings from it. ‘Black roof country’ is in there, you can read so much meaning into different parts of it, it feels quite deep at times.

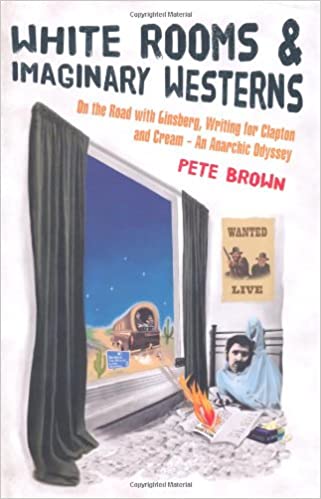

I think the thing that’s made it last is the fact that there is a certain mystery about it. It’s very cinematic in a way. It jumps around from position to position. I’ve got different kind of persons telling it and a lot of images in the middle, of emotions and stuff like that. I think that’s what makes it interesting. It’s not straightforward at all. In its way it’s quite, I guess you would call it sophisticated, but people seem to understand it on a basic level which is great of course for me and I’m very proud of it. I love the thing. I still sing that now as well, sometimes. It was a time when I was going through a watershed period of changing slowly into what I became and so it’s all about that really in some ways but it’s about everything and being in London at that time and the need to travel. I mean it was written in the actual, well the original poem anyway, was written in the white room itself. There was a room that I had in someone’s flat that was one of the first places that I rented ever and so I actually wrote it in there. That’s why it’s in there because it’s real.

And so around the time that Cream were dissolving, Jack was, I assume, starting to formulate plans for his first solo album which became Songs for a Taylor. Was it just a natural process to continue working together?

Yes. I think it was. There was that chemistry and we’d already got quite a lot of success. We were already kind of known as a songwriting duo and so I guess the obvious thing was to carry on, which we did. For 48 years. Must be one of the longest ever songwriting teams I think. I’m not sure what’s the longest. Lieber and Stoller perhaps? I’m not sure.

And ‘Theme for an Imaginary Western’ is a song that resonates for many people now. I’ve heard that was linked to Graham Bond. Is that true?

Well, yes. Because the thing about the Graham Bond Organization was that they were like a kind of mixture of cowboys and pioneers, or outlaws and pioneers. When I first heard the music for that song, which came first, then I actually thought well, I’m a big fan of westerns – I’ve got a big collection of western DVDs – and I thought, well, it sounds like it was reminiscent of some of the great western scores in many ways. It reminded me of Dimitri Tiomkin (High Noon, Gunfight at the O.K. Corral etc) and what’s his name? I forget. But Jerome Moross (The Big Country, Wagon Train etc). A number of people that were specialised in western film scores, particularly Tiomkin, who I loved anyway. I loved his work. So it seemed obvious that it was going to be about some kind of western type situation. And then it came to me that it was about Graham and Dick and Jack and Ginger, who were, as I say, they were pioneers in what they were doing and also in many ways they were outlaws, partly because, although I think that was the greatest ever British band – it was to musicians what the Beatles were to the public in many ways – but although I think it was the best British band then they were not beautiful. None of them were beautiful. I mean they were sexy but they weren’t beautiful. And they weren’t like pop things or anything like that so they were more like outlaws in many ways.

And so we talked at the start about how you were performing originally as a poet but that developed. So when we did you start thinking about branching out yourself as a performer?

Well, as I say, I was making a very thin living doing poetry readings of my own work. It got better after we did the Albert Hall thing in 1965 with (Allen) Ginsberg and (Lawrence) Ferlinghetti and all these guys and we got better known through that. Then the next year was the year that I started writing for Cream and through actually having a toe in the music business, as it were. I always wanted to be a musician anyway, although I never thought I would be a singer. I was having trumpet lessons and playing percussion and stuff like that and when we got the Battered Ornaments together in 1968 I thought I’d be allowed to play trumpet. Actually I was a rotten trumpet player anyhow so the guys in the band said to me ‘Well. None of us can sing, so you write the bloody, songs you f**king sing them.’ And so that’s what I did. Very badly to start with. For a long time I was not a good singer for a long time but then things happened and I did six years of singing lessons later on.

We have ‘Dark Lady’ from A Meal You Can Shake Hands With in the Dark. That album. What are your memories of writing and recording that song in particular well?

It was very influenced by Graham. You can hear that it’s not as good as what Graham was doing at the time but it certainly was influenced by Graham and it was about this particular woman who actually was a sort of Carmen figure amongst the musicians. She was very, very, very sexy and everyone fell in love with her and people used to fight over her. I’m a pacifist and I nearly got into a fight. It was terrible really and so it was really about her. She’d get you into terrible trouble.

But your time with the Battered Ornaments didn’t last?

No. Only a year, just over a year. They notoriously fired me just before we were going to play with the Stones in the (Hyde) Park. So they did it without me which was actually a mistake but, no, they decided that I wasn’t a good enough singer, which was true at the time. Quite honestly I would have fired myself if I’d have had the courage… But, anyhow, it was all right because the next thing I did was I formed Piblokto! and that was more of a musical sort of thing that lasted for quite a long time and I was able to actually get my chops going and I was in very, very, very good company with that band. They kind of nurtured me a bit and I did improve a bit – to some extent, anyway. So that was good. Piblokto! was a hell of a band. Jim Mullen and all those guys in it. They were fantastic. I listened to that every now and then now and I think ‘Christ. What a band’.

Yeah. When you hear ‘Thousands on a Raft’. The Battered Ornaments seems very of its time whereas the ‘Thousands’, as an example, it’s got a bit more of a classic feel and doesn’t date as much.

Oh yes. I love that song. I still sing it. I still do because it’s another one of those songs where I wrote it and I thought ‘Okay. Well, I like the sound of this. This is all right’ and I didn’t really know what it was about. Again, I wasn’t sure. And then, over the years, I began to realize that I’d predicted a whole lot of things that were going to happen in my life later on. So that was what partly about. I love that song. I played it before the Covid thing. The last gig abroad that I did was in Vienna and it was a full house. It was really well attended. I sang that and this guy came up to me at the end and said ‘Oh I cried’. He said he cried because he thought it sounded so… Obviously I’m singing a hell of a lot better now than I used to, so it’s got more emotional impact and everything but, yeah, it’s a very important song to me. Very.

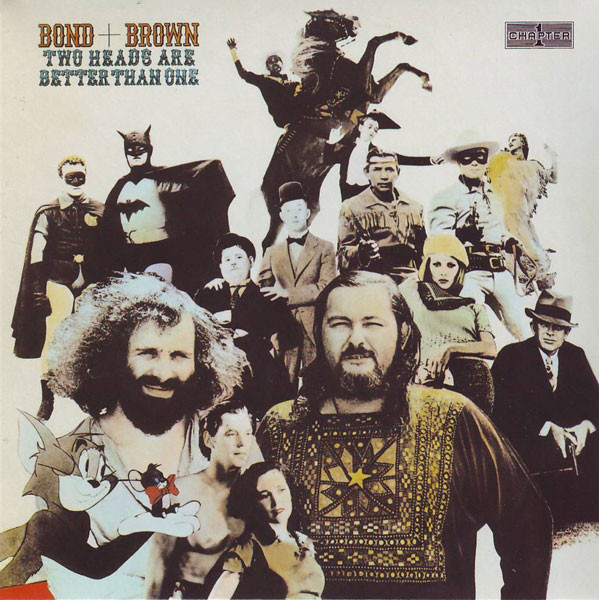

And then you formed a partnership with Graham Bond?

Yeah. Right. Now that was the second and third versions of Piblokto! with Phil Ryan on keyboards, who became one of my closest friends, and we carried on working until he died a few years back. I jumped at the opportunity to get a band together with Graham in ’72 and well, actually, towards the end of ’71 really. We tried hard. We made a record. We did lots of gigs. Graham was damaged by his time with heroin and so it was very unpredictable, to say the least. But we did some great gigs, toured a lot in Europe and did some festivals. All sorts of things. But it was something. That was the best trumpet playing I did as well. I was playing a bit of trumpet with that and that was probably the best. Graham was a man who inspired you and, unlike a lot of great musicians, he also encouraged you. If you got up on the stage with Graham you would always do something that you didn’t think you could do, because he had that effect on you and that was fantastic for me. It was great. Towards the end of it the drug thing got too much again and the performances started to suffer and in the end I bailed. Graham was somebody that I loved as a musician and to some extent as a friend. As I say, you never knew quite where you were with him but he was an amazing guy in many, many ways.

And when you listen to that album Two Heads Are Better Than One (by Bond+Brown) and tracks like ‘Lost Tribe’ were you more musically confident by then and were you playing a greater role in the musical side of things?

Yes, a little bit. And, yes, absolutely and Graham, as I say, was really, really encouraging and inspiring and so I did take a slightly bigger part in that and in fact ‘Lost Tribe’ was… The thing in Britain – the scene – was starting to change and die and so we found ourselves on the road in Europe a hell of a lot where we were appreciated a lot more and that’s where the idea of the ‘Lost Tribe’ thing came from.

Great. And, as we were discussing earlier on, the ever-present element of your career was that incredible partnership with Jack that you had. Despite the vagaries of the music industry and the shifts in sounds and whatever, that seems to be an ever-present thing so even by 1980 you were there with Jack. ‘Bird Alone’ is a great favourite from his I’ve Always Wanted To Do This album.

Yes. I mean. We went through lots and lots of different changes really. Jack was a very, very open-minded man. Musically he listened to a whole lot of different things and was inspired by things as diverse as the obvious things like Charlie Mingus and then soul things like Joe Tex and then he also was very capable of playing classical stuff as well. And he loved Olivier Messiaen, who was very important to him, and so it was always changing, which was great for me because we never got into a rut or anything. There was always a new challenge and of course we did have much more time to work on stuff. And it just lasted and lasted. Yeah, we had some fights. We didn’t speak to each other for a while, every now and then, because we’re both highly developed personalities and having the two of us in the same room sometimes didn’t always work. And then Jack had problems as well later on with nasty substances and so, which I didn’t. I got completely straight in 1967. I stopped drinking and taking silly drugs and stuff like that completely and utterly. I’ve never touched anything since and so it was kind of a bit difficult. But I got used to it and mainly I could function under that particular strain, mostly. Every now and then I walked away from it or he walked away from me. But mostly we stayed there and then we hadn’t talked for a while when we did the last record together – towards the end of it anyway. But ‘Bird Alone’ is. We both love Charlie Parker so that was Bird. Bird was Charlie Parker. But, at the same time, it’s the title of a very, very good book about Ireland by a very famous writer called Seán Ó Faoláin which has an atmosphere to it as well, with very amazing atmosphere in that book. So I sort of mentally combined Charlie Parker with this Irish writer in my mind and that’s how that one turned out.

And just outside of your songwriting partnership with Jack in the 80s and 90s, what were you doing as well because I know that in that period, outside the music industry or performing, you did a range of things?

Yes. Well, when the punk thing came along I was completely horrified by it and thought that it was something that was destroying the skill base of British music. You couldn’t get a record deal at the time because they just wanted people that couldn’t play and that looked right. I had a great band, at the time, called Back To The Front. Full of absolutely amazing musicians like Ian Lynn (keyboards) and Jeff Seopardie (drums) and John McKenzie sometimes on bass. We were doing well because people hated punk live. A lot of people couldn’t stand it. And we played in places where the punk acts had played a couple of days before and they told us how much they hated it. Unfortunately the punk thing was something that the record business invented and rammed down everybody’s throat and I won’t say any more about it because I start ranting… And so, after the failure of Back To The Front, which was partly me because I, once again, thought that, being such great musicians, I wasn’t doing my job enough. So I felt, I’m going to stop and I’m going to try and learn to do this properly even if I never do another gig again. So that’s when I started having singing lessons – towards the end of 1977. Meanwhile I wasn’t doing any gigs at all. I just gave up and started trying to write film scripts at a time when there was no British film industry at all and Margaret Thatcher actually thought that the British film industry was full of communists which was completely and utterly untrue and tried to destroy it as a result. At that time, we were making about 30 films a year, most of which were for television, and so they called them plays but actually they were proper films. People like John McKenzie directing them and stuff like that but some of them were really good. Phil and I did the music for one of them called Red Shift which was an Alan Garner book. It was really good. Anyway, so I was writing. I actually got a very good literary agent and he got me quite a lot of work but a lot of the things that I wrote never got made. I think they were too idiosyncratic, really, but I still do that. I’ve got a very good partnership with a young director and I’m still trying to get my scripts made and there is some possibility of that at the moment, so that’s good.

That’s great to hear. When we were talking about ‘Bird Alone’ you were leading into the final album that Jack made, Silver Rails. You’d said that around that period you hadn’t actually spoke to Jack for a while?

No. I won’t say why, but I was pissed off with him and then I got the call. I knew he wasn’t well and he’d done himself quite a lot of damage over the years and he said ‘Yeah. I’d like to do a new record. I want you to work on it.’ and I would realize what it meant and so I went ‘Absolutely. No problem at all’. I was there. And we wrote some stuff that I’m very proud of and, funnily enough, actually, when you’re talking about sales then obviously the first Songs for a Taylor sold very well and was in the charts and then, apart from some of the stuff that he did with other famous people like West, Bruce and Lang and the stuff that he did with Robin Trower which actually did get into the charts, none of his solo albums got very far although now it seems like a very important body of work and people really revere it but then Silver Rails actually sold really, really well. Yeah. So that was very good. It kind of vindicated the work a little bit.

When you hear ‘Reach For The Night’, for example, it seems to have a particular extra edge given that Jack..

He was dying, basically.

Was that just something that you’d had already?

No. I’m pretty sure he played me some of the music to that. His son Malcolm, who I work with quite a lot these days, Malcolm actually helped do all the demos. And when they played me that over the phone then I was really absolutely blown away. Well, I was in tears, actually. I thought that was amazing what he did with that. It is very powerful and heavy, emotionally, but that’s what music can be about and should be about sometimes.

In recent times I’ve spoken to Gary Brooker and we reflected on the Novum album which he made with the current line-up of Procol Harum. How did you get to work with Gary and the group?

Well. I’ve come across him quite a bit over the years because we belong to the same generation and I always liked Procol Harum. I thought that they were a very musical group. I liked a lot of what they did. Particularly that Homburg album. I really like that one. But I like a lot of the other stuff as well. I think it’s good and my very good friend Dennis Weinreich, who was a great engineer and producer called me to say, would I be interested in doing the lyrics for this new record that they were going to do. Also their manager, who just died actually – Chris Cooke – who was a lovely guy. He also came on and said he’d like me to do it. He thought it was a good idea blah, blah, blah. So I had a go at it and I thought a lot of it came out pretty good. I mean, it was odd because I’m an old lefty and they are not. So there were some divergences of opinion about certain things and also, on the other hand, I managed to sneak some things in there which were probably not what they thought they meant but I know what they meant. So, yeah, it was an interesting idea because, I don’t know if you realize, because originally when I had a meeting with Gary and I said ‘Have you got any themes in mind? You know, any ideas about it things just so I can get in my mind in the ballpark, sort of thing?’ and he said ‘Ten commandments’ and I went ‘Okay. Now, I went to a religious school. I hate religion deeply. I think it causes an awful lot of trouble in the world, I’m afraid. Anyway, I thought this is an opportunity. I can do some of my very cynical sort of things, being a cynical old bastard. So I proceeded to do it and I made it in such a way that it’s ambiguous. Of course it is. A lot of it’s ambiguous. I mean it could mean whatever you want it to mean really. I know what it means but and I mean, musically, I thought it was really good. It was a really good record so I’ve got no problems with it musically. I might not choose to do it again but certainly it was something that I probably needed to do once in my life. But they’re all great musicians. Terrific. And Gary’s got one of the great voices.

He does. And now we’re moving to a pair of tracks from what many people regard as your best album Perils of Wisdom and you made that with Phil Ryan. The first track that we’ve got here is ‘Motormother’. How did your partnership with Phil develop over the years because you have recorded quite a few albums with him?

Yes. We’ve done a lot. Well, Phil and I were both kind of pretty strong left wingers and originally, when he joined Piblokto!, we used to fight quite a lot because, by that time, although my background is working class – the same as him – but by that time I had become a wealthy songwriter or relatively wealthy. I loved Phil from the moment I saw him. Phil used to be in a band called the Eyes of Blue which was one of the great, great bands. They were all Welsh. They were from the South Wales area and they made some records which are terrific. Should have been much, much bigger. I was working in a place called Middle Earth. Before I started singing I had this band called the First Real Poetry Band with John McLaughlin on guitar and we were doing our jazz and poetry thing and Phil used to play down at the Middle Earth regularly and so I used to hang around there and chase women. I got to hear him a lot and got to know him a bit. Wrote a couple of songs with them which never actually got recorded and then, of course, when they broke up, I grabbed Phil for Piblockto! and we were together for a couple of years there. He joined Man, of course, and that was the most successful period of the Man band and then I wrote a few things for them and went and played on a couple of their records, played percussion and stuff. I realized that after the Back To The Front band broke up what I really needed in my life was Phil in order to write the things that I wanted to write.

The more personal type or idiosyncratic types of thing and so we got together again and we started making demos and then we formed a live band which is called The Interoceters which lasted a few years and started making records. Underfunded records but, nevertheless, I think there’s a great deal to be gleaned from them. I love those records and the last one we did which was Perils of Wisdom which we had to do fairly quickly due to financial limitations. I love the thing. I really do. And I think it’s some of the best work I’ve done. Phil looked after his wife for nine years. She was very, very ill and so he couldn’t always do the gigs. Eventually he couldn’t do the gigs at all and so I just went and had the band myself but then, after his wife died, we managed to do more gigs and record a bit more. That was the last thing we did there. We were planning another one and then of course he went and died. Perils of Wisdom says a lot of things that I always wanted to say and of course ‘Motormother’… It’s quite a sort of humorous lyric, in a way, but ‘Motormother’ was this kind of weird contradiction about the obsession with cars; cars being very womb-like but also very penis-like as well. I remember seeing a program. Quite recent actually. The last couple of years. About sports cars and one of the kind of guys on the commentary pointed out that the E-Type Jaguar was meant to be a sex symbol. It was meant to be like the curves of a woman but with the punch of a penis and so I thought, well, that’s a very interesting contradiction. I’ve always wondered what psychologically and what the subtext was about. Neither me nor Phil have ever been a driver. We’ve never driven cars. And so I wondered what sexually where we were at with people’s psychological relationship to cars and that’s where that song came from. I actually think it’s one of my better humorous songs. I like humour. I think it’s important.

Although you said it was underfunded and recorded quickly, it doesn’t show on songs throughout the album including ‘Eva’s Blues’, for example. It’s a really good sounding record.

We did the best we could. It was in a good studio. It just could have done with a bit more time but yeah, ‘Eva’s Blues’ – I originally wrote it to give to somebody else and then they never bothered with it so I’ve looked at it again and, by that time, the Amy Winehouse phenomenon was happening. I thought Amy Winehouse was a terrific singer and a damn good songwriter. I was very much on her side actually. I liked what she did. But I could see the dangers in how she was and so I kind of invented this narrative which, although it wasn’t really about her, but in some ways it was. It’s a song that’s grown over the years. I sing it now quite a lot when I do gigs and I think people seem to really like it and sort of understand what it’s about. So that’s pleasing.

You’re still producing new music, like the last three Krissy Matthews albums. But to close you’ve also recently worked with Joe Bonamassa. We have ‘When One Door Opens’ which is one of the singles from Royal Tea. How did that collaboration come back?

Well, one of my managers, who shall be nameless, tried to get us together because he interviewed him for something or other and that didn’t really happen. But then I got involved with a project which is called Cream Acoustic. It’s a record and it’s also a film. It was made over a couple of years from about 2019 onwards.

That’s with Mark Waters – he’s the young director of the Cream Acoustic film isn’t he?

Yeah, it’s an all-star thing. It’s got Bobby Rush, it’s got Joe Bonamassa and I’m singing on it as well. But I’m also one of the executive producers. So that’s coming out in June of next year (2022) and I was on the Joe Bonamassa session. I was there in my capacity as one of the executive producers and we got talking and that’s where it came from really. He eventually called me and said, ‘Okay. I’ve got this thing coming up and would you like to do some stuff?’ and did some stuff and some of it worked so it was good. And now that album is nominated for a Grammy. So that’s good news.

Absolutely. And you mentioned the Cream Acoustic record so that’s due to come out in the middle of next year.

Yeah, June. It’s got everybody on it. Maggie Bell, Deborah Bonham – female contributions. Nathan James – I don’t know if you know of him – from the Inglorious band. Incredible singer. The last sessions ever of Ginger Baker. He plays on four tracks.

Wow.

Bernie Marsden (Whitesnake). Yes. The list is endless. Lots of great people.

And have you got any other plans for next year? You going to try and go out and possibly do some dates?

So, yeah, I’ve just started doing some gigs. They’ve dried up at the moment because of the uncertainty of what’s going on but, if things get better next year, certainly I’ll go and do some gigs and also I want to try and make a new record. The producer of the Cream Acoustic record is a great guy called Rob Cass, Irish guy, who’s a fantastic producer. He also produced the Silver Rails as well, which is how I met him, and he wants to do a record with me so we’re trying to raise money for that at the moment, see what we could do with that. And, yeah, I’d like to do that before… I am too old but, I mean you, know I’d be 81 on Christmas Day (2021) but, yeah, I’ve got a lot of new songs that I’ve mostly been writing with people that I’ve worked with over the last few years especially a guy called John Donaldson who’s a great keyboard player. He lives down the road from me in Hastings. Mo Nazam, who was my guitar player in The Interoceters for eight years. And I’m going to try and include at least one song that I wrote with Phil Ryan that’s never got recorded and another one with John McKenzie. John McKenzie was our bass player. He died this year. So I’m going to do one that I wrote with him. Gonna do one that I wrote with a very, very good American musician called Carla Olsen.

Oh yeah.

You know her?

Yeah. Absolutely.

She’s a producer and writer and guitarist and singer. We’ve been writing some stuff together and there’s one particular song that I would quite like to put on this record if I get the chance. So, yes, there’s plenty of stuff. No shortage at all.

What a remarkable story and music that you have and I wish you all the best for 2022. It sounds like it will be a very busy year for you.

Hopefully. Well as long as we can all stay alive then that’s the main thing.

Further information

- Pete Brown’s website: petebrown.co.uk

- Look out for details of the Cream Acoustic Sessions at Quarto Valley Records: quartovalleyrecords.com/cream-acoustic-sessions

Acknowledgements

Transcript and extra research provided by Nigel Davis.