By Brian R. Banks

Through changed line-ups and musical epochs still continuing today, Medicine Head conjures up links aplenty for both ’70s and later generations, from an unforgettable gig or T.V. slot to a wedding accompaniment. Phil Collins responded to a BBC interviewer “what other band would you have liked to be in?” with “Medicine Head”, once listed in the Guinness Book of Records for the longest UK tour when a dozen encores weren’t unusual. Their first airplay provoked Lennon, Manfred Mann and Pete Townshend to ring John Peel about “one of the few truly original British bands that can be counted on the fingers of one hand”. This is quite a story in anyone’s book.

Two Librans John Fiddler and Peter Hope-Evans, fellow school pupils and then at Stafford Art College, bonded through mutual taste for American folk-blues into an instant rapport. The Midlands was then a musical melting pot since the 1950s developing with the Rockin’ Berries, the Sound of Blue (who became Chicken Shack) and even Radio Caroline’s theme song by a local The Fortunes. The list is long, from Black Sabbath and Judas Priest to Roy Wood’s Wizzard, Slade, Traffic, the Move and Moody Blues as well as Kevin Coyne and Nick Drake. Folk and skiffle were well-bedded there too, and as compilations as early as 1964 show, the breadth was much wider than say Merseybeat. Music genres also have roots there: heavy metal, grindcore, two-tone and ska revival to name a few.

There was also a deep interest in blues, and the area was a stop-over for legendary blues tours and festivals which the foot-sore students attended. The origins of that raw sound, mixed hubble-bubble by the various phials of creativity around them, were reflected in their initial experimentation with piano, dual harmonicas and jew’s harp. A lucky inheritance from Peter’s family saw a first guitar and drum, a huge 32” vellum-skinned thumper soon decorated with a valley scene by a close artist friend for early promo shots.

First suggested names included The Mission (they briefly worked in a cemetery so perhaps the first songs were inspired by the elegiac epitaphs and statuary) or Dr. Feelgood & the Blue Telephone, but settled for Medicine Head because, literally, good medicine for the head. The ethos came from ‘lone cat’ bluesmen such as Jesse Fuller, Dr Ross, and Joe Hill Louis, one-man bands who played everything themselves in a DIY spirit. Free festivals, sometimes with a club gig the same day, also encapsulated this spirit resulting in red-hot intensity of composition anytime-anywhere. Songs were penned backstage then tested live; if didn’t ‘bite’ then they were dropped. A couple of these spontaneous nuggets are still listed in BBC archives.

The point has always been to transmit emotion, each instrument (and its different sounds) chosen to convey a specific feeling, from Robert Johnson’s ‘Walkin’ Blues’ (also used in Son Houses’ ‘Death Letter’) that’s a staple still today to ballads among the best anywhere. Legend has it that they turned up at Wolverhampton’s Lafayette club claiming to be the support act and played until the booked band arrived. The DJ John Peel probably only heard a snippet but it was enough, and the rest is history…at least for the next five years of fame with its gorgon aspects.

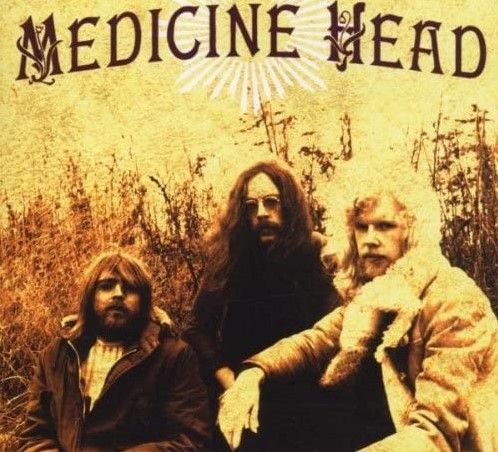

The unusual configuration of John Fiddler (vocals, guitars, harmonica, bass drum, hi-hat) and Peter Hope-Evans (silence, harmonica, jew’s harp/mouth-bow, percussion) were among the first to be signed to John Peel’s new Dandelion Records, unaware that they’d become the label’s biggest-selling act in its short three-year span. The charismatic DJ, who loved music and creativity above all, has never been forgotten by the Dandelion artistes even though his heirs don’t respect the legacy.

The venue stage was unusually sparse at a time when lumbering proggers lugged tons of equipment: two chairs (they both initially sat) fronted by two microphones, a bass-drum, hi-hat, Fender Strat for power, and a creamier-sounding Gibson ES 330 fed through a Vox amp each for John and Peter. The trend was to expand line-ups not contract them, but as openers for rockers the combo turned up the decibels to blow bigger bands off-stage, so it was better to rebook them as headliners instead!

Their atmospheric Peel-produced debut, New Bottles Old Medicine (1970), like the band’s name, reflected this heady brew of storm-rousers in the Hooker mode juxtaposed with spiritual ballads, hauntingly simple yet articulate. It’s often thought that the first 7”, ‘His Guiding Hand’/‘This Love of Old’ (1969), came from the album session but actually it was a raw demo version. When Lennon and Yoko Ono were played that kitchen-tape from a Grundig reel-to-reel, they suggested it be released undoctored, the same feel as on their BBC debut in December 1969. The album was done in a couple of hours at CBS’s London studio: illuminated with candles, it captured their live set to carve a niche all their own that was later smuggled chart-wards under the guise of quirky, beguiling pop-rock.

‘Coast to Coast’/‘All for Tomorrow’(1970) tickled the chart with a heavier sound then the Keith Relf-produced ‘(And the) Pictures in the Sky’/ ‘Natural Sight’ (1971) became the only Dandelion release to chart at #22 during 8 weeks. The four sides, from the belter ‘Coast to Coast’ to the deliciously swampy ‘Natural Sight’, are all non-album gems in true underground ethos. Head’s homemade elixir driven by a thumping bass-drum/hi-hat with rhythm /lead guitar has been called ‘proto-punk’; one reviewer saw the microcosm of Medicine Head as the history of rock ‘n’ roll in a particular English style.

It was a kindred spirit that delta bluesmen honed inside basic studios and on the road. One moment letting loose with searing riffs then out-open with melodic ballads, their gigs were always fresh due to a prolific partnership and unusual trademarks such as simultaneous harmonicas. No guitar solos—replaced by harp ‘leads’ when not replicating drone-pipes—no synthesiser tricks, and definitely no drum work-outs, the astounding rhythmic array in a simple format drove an infectious boogie to smile and dance to. Hope-Evans wailed and puffed locomotive-like down the mountain-track, swaying with his appropriate dandelion mop then jumping off-stage to snake through an astonished crowd. No one forgot the sweaty encores when a medley of classics (loosely) based on Carl Perkins or Little Richard were interspersed with surprising covers such as Dylan’s ‘(Just Like) Tom Thumb Blues’.

“We saw ourselves as blue-eyed San Francisco Bay blues guys,” John recalls, ‘we didn’t consider ourselves musicians: it was pure, unadulterated emotion with whatever percussion was to hand’ and could be replicated in every home! His modesty masks the fact that albums, original variants on integral themes, show evolving sounds often unseen by critics to stand the test of time remarkably well. For Heavy on the Drum (1971) the mystical depth was less overt but lyrically still hypnotic while rockers such as ‘Medicine Pony’ became live standards building to crescendos hard to imagine for a duo. With one of the most distinctive voices—and strongest pins!—in the game, it was startling how much came from a rudimentary ‘rhythm section’. This highlighted a dilemma that John Peel also realised: how to transfer the popular live sound to vinyl? Improvisation and layered texture might dilute the initial spark. At one free Marquee show recorded by Polydor (for One & One Is One) they incredibly carried on playing with busted strings and drum-pedal while the roadie desperately did hasty repairs Blowing holes out of a harp or fraying guitar strings whipped up an energy transferred to their record of over 20 Radio One sessions from 1969-1977.

Hope-Evans left before an impending US tour so Keith Relf (Yardbirds, Renaissance) on bass (as on their first hit single too) and John Davies on drums joined as a trio for Dark Side of the Moon (1972). Pink Floyd thought that title better for their next album Eclipse so waited to see if Head’s charted before nicking it a year later. Fiddler’s rumbling vibrato mesmerising as a rolling river, features here as on the last BBC session and Don’t Stop the Dance (Angel Air Records 2005) where the 1972 title-track first surfaced.

After Dandelion Records blew away, Hope-Evans returned for One and One is One (Polydor 1973), produced by Tony Ashton (of charters Ashton, Gardner & Dyke), which spawned the band’s biggest hits that year. The title track (backed with an acoustic ‘Morning Light’ later electrified for a German compilation) reached #3 during 13 weeks, then ‘Rising Sun’ with the non-LP ‘Be My Flyer’ peaked at #11 along with worldwide top tens and big Euro-tours. Critics seemed perplexed when they couldn’t pigeon-hole this development, Kenny Everett calling the second hit ‘psychedelic reggae’ but Fiddler said it was inspired by Fats Domino. On Top of the Pops, when Head was on every mag cover from Melody Maker to Jackie, Tony Blackburn embarrassed all with a tambourine as if a novelty sideshow. They are an LP band and, like verses not transplanting well from books, the fame of singles was the beginning of the end for ‘the world’s biggest small band’.

They toured bigger venues as a five-piece, but the founders thought this lost more than it gained by the otherwise superb additions; the spontaneity and creative spark (“its heart and soul”) diluted by expansion, though hard to notice due to a prolific repertoire. Hope-Evans (whose session work includes Ronnie Lane, Family, Edgar Broughton Band and Tears for Fears) felt relegated from partner to side-man, especially live. The cross-over from message-bearing underground musicians to hit-makers was tricky, though they never sacrificed credibility. Thru’ a Five (1974) brought a funkier soul medicine via clever arrangement, clearly heard on ‘Slip & Slide’, John’s favourite hit (#22). After a couple more 45s in that style, the quintet folded with a fine Peel session in 1974 when the first compilations appeared.

Two Man Band (1976) on Chas Chandler’s Barn Records, recorded at Pete Townsend’s Eel Pie studio, featured a reggae horn section, funk, and nods to such as Sam Cooke and Buddy Holly in some of the band’s widest styles with new instrumentation. After six albums in as many years and countless gigs that could make a progger pale, the album signified the duo’s last studio fling except for a BBC session the next year that included a stomping reprise for ‘Pictures in the Sky’ on Before the Fall (Strange Fruit 1991).

NEW HOMEOPATHY

After the demise of the successful Mott the Hoople, Fiddler fronted its rhythm section as the post-glam British Lions. This strutting combo (self-dubbed the Loins!) tore through the hits of both bands together with new songs mostly written by the ex-Head for two albums, US tours and success in Japan until 1980, when a couple of singles on Harvest with Ray Majors heralded John Fiddler’s solo work.

He regrouped with some ex-Yardbirds as Box of Frogs, a moniker that was to be unfortunately ironic: as he told a US radio interviewer, it can mean not a pretty situation. John Fiddler was involved in all the song-writing for two studio-layered records, featuring ace harp-blowing by Mark Feltham of Nine Below Zero and class cameos by Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, Rory Gallagher and Steve Hackett among others. Garnering great reviews and stateside radio play, the band was scuppered, alas, by some Yarders not wanting to tour. It was additionally galling because such legends as Mick Moody (Juicy Lucy, Whitesnake), Boz Burrell (Bad Company) and Ringo’s son Zak Starkey had invited John to front their new band which he had to contractually decline.

After a return to radio in 1990, for the Andy Kershaw Show, John Fiddler has recorded evocative albums without a hint of padding and a live acoustic DVD (2004) that reflect enduring devotion to his art spanning decades and, like the Head reissues, universally well-reviewed. His songs sound fresh and vibrant, they never stagnate but flow through various styles of good vibes like a life-giving spring. He has also remained true to his early pictorial art which he studied before his music career and are on his website.

John Peel always enthusiastically called Medicine Head a rare treat, with not one but two of their singles uniquely in that connoisseur’s always-to-hand box. Their debut has been re-released by Cherry Red Records in a 50th anniversary edition with a bonus disc of non-album singles, BBC and live recordings including the Marquee. Jack White went on social media to say how he liked playing this album. Fame brought its clamour but the essence never deviated with unforgettable heart-hitting lyrics as compilations testify. An intoxicating new album Warriors of Love is out now on Living Room Records (see medicinehead.rocks). No wonder fans number such diversity as Nico, Bobby Gillespie, Joe Perry, David Tibet, Peter French, Pete Townshend, and Mick Moody. A timeless experience through evolving incarnations, like unearthing a rare treasure or bumping into a living legend.