By Jason Barnard

Woody Woodmansey reflects on his time in the Spiders From Mars including the moment David Bowie announced his retirement as Ziggy Stardust.

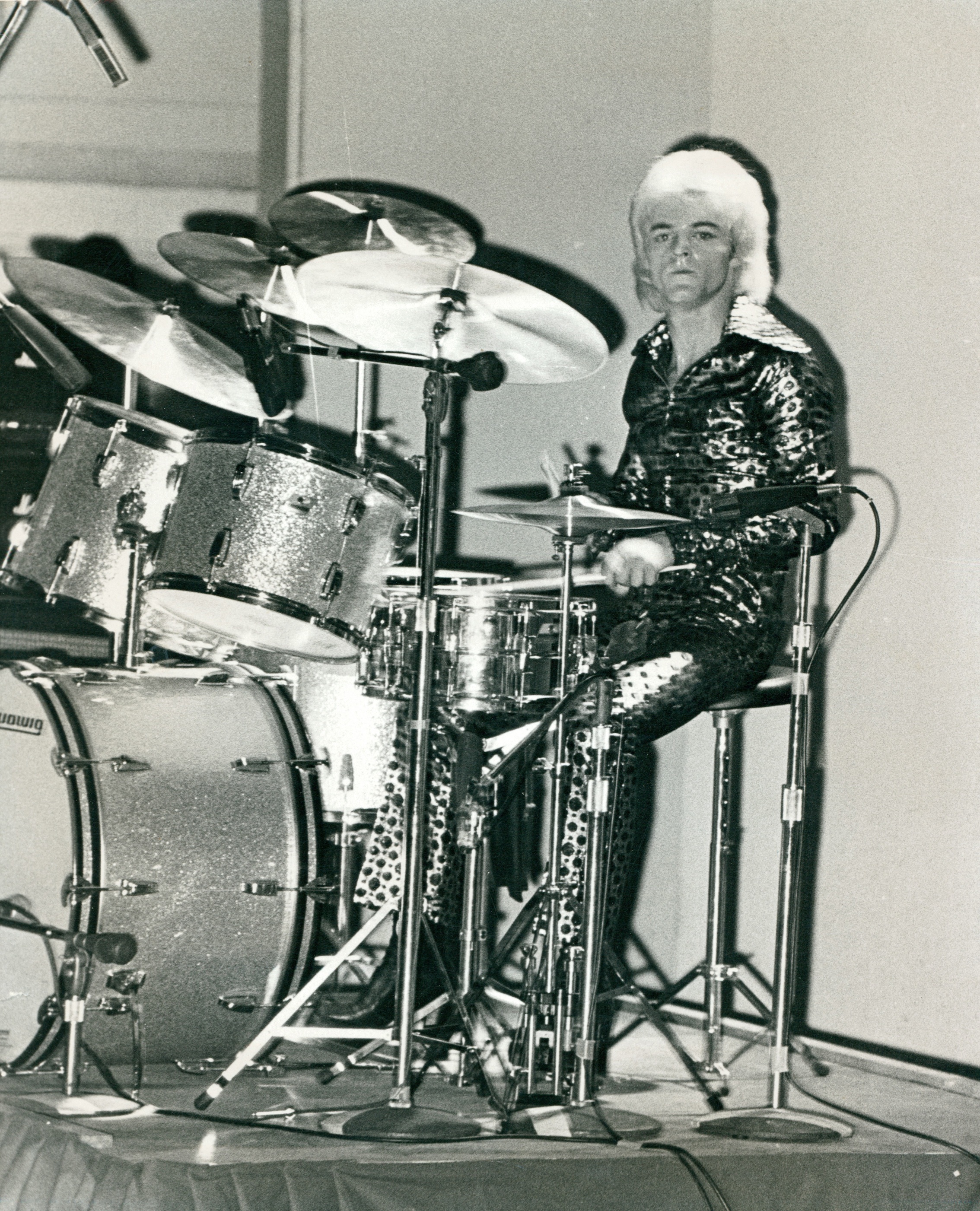

Woody Woodmansey by Mick Rock

Did you ever play an album in its entirety with David back in the day?

No. I think if we did it, we did it once and I don’t know where that gig was, but generally we didn’t because I guess there was so much of the material in and some we didn’t consider at the time work live. I think we did ‘Lady Stardust’ just once. ‘It Ain’t Easy’ we never played live, so there’s quite a few we didn’t do.

‘The Man Who Sold the World’ album is quite unique in David’s canon, in that it was a much more collaborative process than some of his later work.

Yes, I guess it was his first move, really, into rock. When we joined, it was still kind of David Bowie folk guitarist. Mick [Ronson] and I particularly had just come from progressive music, anything from Cream to Zeppelin, Hendrix, Jeff Beck Group and the blues. That was our background. So it was taking what David had written and that’s kind of the mode we were in at the time. We always looked at it, as our Sgt Pepper. It was everything but the kitchen sink on there. It was a shame we didn’t get to play it live at the time because there’s a lot of dark songs on it that we really did want to take out onto the road. It’s been funny doing it because you never imagine people singing ‘All The Madmen’ as a pop song. The audience sings along with you and you’re singing about some dark subjects and they’re singing along like it’s a pop song. It’s quite funny.

The thundering drums are fantastic on ‘The Supermen’.

Thank you. Yeah, that was originally called the Cyclops, which is probably why it thunders. [laughs] I said, ‘What’s this one?’ Because he hadn’t done the lyrics to it, said, what’s this called? He said, ‘It’s the Cyclops’. So we just imagined a big monster with an eye on the forehead and we played with that kind of an idea in mind. And then he said, no, change it to Supermen. I said ‘It still works.’

Tracks like ‘She Shook Me Cold’, which are not as well known,have got a real harder edge sound.

That’s an amazing track to play. It’s quite tricky because there’s some odd stops and starts in it. I always thought it was probably one of the dirtiest, meanest guitar intros that I’d ever heard. And I still haven’t heard anything that’s quite as rude when it starts as that. And it just really fitted the song over.

Interesting thing is, because it was so collaborative with the wide range of percussion on songs like ‘The Man Who Sold The World’ itself.

Yeah.

It must have been invigorating to be able to experiment and bring other percussive elements in.

It was because I was strictly a drummer. I remember during the album, Tony brought in percussion pieces on that and he handed me this thing, look like a big wooden sausage, it was painted red at one end and green at the other, and had these ridges in the middle of it and a hole in it. And he said, do you want to put this on ‘The Man Who Sold The World’? And I was like, I didn’t want to appear ignorant. So I kind of looked at it, I took it from him, I looked at it, I kind of blew across the hole, thinking maybe that’s what you did with it. He took it back off me, said, ‘No, you idiot, you put your thumb in there. Then they give me a little stick and you tap it and then run across the ridges and it makes a brrrrr sound, you know. I was like, ‘Oh, yeah, I knew that. I was just messing about.’ And then he introduced me to timpani and wood blocks and maracas. I’d never really played all that stuff, but he was really good at showing somebody really quickly, or I was really quick at picking it up. I’m not sure which. Probably a bit of both. But it was fun, it was good experimenting like that.

For ‘Hunky Dory’ it seemed that you adapted your drumming style to fit the music and didn’t overplay as much. Is that something that you recognise?

Yeah, that was really a conscious effort from all of us, really. We kind of got into listening to Neil Young and Crazy Horse and John Lennon’s solo stuff. And it was apparent, which we hadn’t really looked at before, that you could put a song across really well without doing licks at 1000 miles an hour, basically [laughs] not getting your favourite lick into every song you do. I remember listening to a Crazy Horse, a Neil Young track, and it was a very simple beat. And I hadn’t realised that he didn’t play on the symbol till right at the last chorus. And when he did, it just lifted the whole thing and I was like, ‘Wow.’ I didn’t really know that you could do that like that. And then David was kind of bringing us completed songs where they hadn’t been completed before that. So you had all the lyrics and where the vocals were. And you definitely couldn’t thunder across the drums on an important line like, ‘Mickey Mouse has grown up a cow.’ You know what I mean? You couldn’t do a million symbol splashes through that. So it was more streamlined. We streamlined everything to kind of simplify and really to back the song, I think ‘Hunky Dory’ was always for me, Bowie saying, I’ll show you I can write songs, you give me a violin and I can write you a song with it.

It was very varied, that album, but they were all good songs. The songs needed to communicate as the songs, rather than a style or anything. The style kind of came more when we got into the Ziggy material because we thought, well, you can’t really go out and do Hunky Dory as a live show. I would fall asleep. [laughs] Whether that’s true or not that was what we thought – we need to liven everything up, so that’s where Ziggy came in, really. He started writing more rocky things and we could get our teeth into it, but it never went back to the ‘The Man Who Sold The World’ approach where anything goes. It was still streamlined behind the song, which is why it worked, really.

We talked about that lift, and that lift in terms of bringing the drums later, seems to be apparent in ‘Oh! You Pretty Things’.

Exactly that. I always thought John Bonham from Zeppelin was a big hero of mine, and even though he played heavy all the time, if he couldn’t fit that into a song he didn’t play. It was like when I’m in and you’ll notice it, that was what I got from him anyway, so I kind of used a bit of that – don’t play if it’s not going to really add, leave it and then make an entrance when it needs it, when it needs a lift then find the right beat that keeps it altogether.

A great memory from your book ‘Spider from Mars: My Life with Bowie’ is talking about Mick Ronson, the orchestration for Life on Mars and the way that he deals with that situation with a bunch of stuffy musicians.

That was amazing because that was kind of his first big string part and so he had been finishing it off in the bathroom while we queued outside for the bathroom. He was still finishing writing the score and the BBC were pretty straight laced, shirt and tie, we start at nine, we finish at ten that’s the session type thing. The way we looked, they really didn’t appreciate that they were having to work for some rock and roll hooligans type thing. And Mick was really nervous that he had to go out and conduct it and he took the parts out, handed them out and he just stood there in front of them and made them wait and just rolled a cigarette really slowly and you could see them getting more and more edgy. Probably not the best thing to do, but it made him feel better.

Ken Scott, who was the engineer producer on that album, he’d worked with The Beatles and he said that we’ve had these string guys in before on Queen tracks and Beatles tracks, and they really don’t mess about. They just do their job and then go. They played the strings to ‘Life On Mars’ once and it was good. Bowie and I were looking through the glass into the studio and giving Mick the thumbs up, and then the leader of the string section came up and went, ‘Did you write this?’ Mick said, yes. And he goes, ‘We really like it. We think we can do a better one.’ And everybody in the place, their mouths dropped and Ken said, ‘That’s never happened. They’ve never offered to do another one’. They did another one and it was even better, which is the one that went on the track. So it was quite interesting just watching that take place.

In your book, you talk about the moment when David called and you had the choice of getting a well paid factory job, which was a really good job from where you were, or to take a gamble and join David. Now, by the time of ‘Starman’ and Top Of The Pops, did you feel like you’d made it and been justified?

It was a tough decision because I kind of got thrown out of school and my parents and relatives didn’t look too kindly on me. I was kind of the black sheep and accidentally really got good at this job in a factory. I happened to learn all the machinery in this factory and I ended up being the only one unintentionally that could set the factory up. So they offered me at 18, the kind of under foreman’s job. And there were guys there who had been there for like 20 years who were hoping to get that job. In a Yorkshire farming town, it was quite a good job to get. So they said, ‘We need to know Monday if you’re going to take the job.’ And then on the Friday, the same day, David phoned up and said, ‘Mick says you’re a great drummer and you’d really fit in with us. I want you to come down to London. And I’ve got a place called Haddon Hall in Beckenham, Kent. So all your food and rent and all that’s covered and we’re just going to play and I’m going to do another album.

And I was like, ‘Okay, can I phone you back on Monday?’ [laughs] And then it was a hard weekend, really trying to decide, but got there, it took all weekend, basically, just sitting in the lounge. In the book I say that I was sat there and it was going 50-50. This is a good job. Parents and friends all like the fact I’ve got this job, but I love music. But you go through, ‘Am I good enough? Would I ever make it? Is it worth it?’ And then the TV was on and the band came on and I was kind of imagining that I was, like 65 years old and I don’t know who the band was. And I’ve got my grandkids there and I’ve just had a holiday and I’ve got a new car in the driveway. And I said to one of my grandkids, when I was 18, I could have….life kind of went on pause, it just stopped and I went, ‘Oh, that is my life. That is my life. I can see it. If I do that, that will be my life and I will regret.’ And I thought, ‘Well, if I come back into my hometown in rags with no money, battered and bruised, and everybody says, we told you not to do it, I can say, Yeah, but at least I tried.’ So I just picked the phone up and rang him up and said, ‘Yeah, I’ll be down on Tuesday.’

And then you ended up on the BBC, radio, TV and also on tour in America. There’s that great Santa Monica 72 show that’s been captured.

It was a dream come true, really. Those tours were just amazing. You’re touring those countries, meeting lots of people, fantastic audiences. We went to the best restaurants in the cities, we went clubbing it afterwards, partying. So it was hard work, but we partied hard as well and it was good, it paid off.

I’ve spoken to Hutch Hutchinson and he talked to me about ‘Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide’ and the surprise in terms of David’s announcement. And then you kind of had to sort of regroup.

Yeah, it was a total surprise. I kind of thought he was going to make some changes, but not that drastic. [laughs] And we didn’t even know, really, if he was joking, because we got used to the fact that he would often do things that were unpredictable that he hadn’t told he was going to do and you had to ride with it, so it could have been one of those. It was only later when we found out now he didn’t want to do the Ziggy thing anymore.

Further information

- This interview is transcribed from a Strange Brew Podcast interview with Woody from 2018.

- Woody Woodmansey’s website.

- Strange Brew written interviews with Ken Scott and Tony Visconti.

- Strange Brew Podcasts with Woody’s predecessor John Cambridge, and collaborators Hutch Hutchinson, Rick Wakeman, Earl Slick. Podcast with Tony Sales (Iggy Pop/Tin Machine) coming soon.