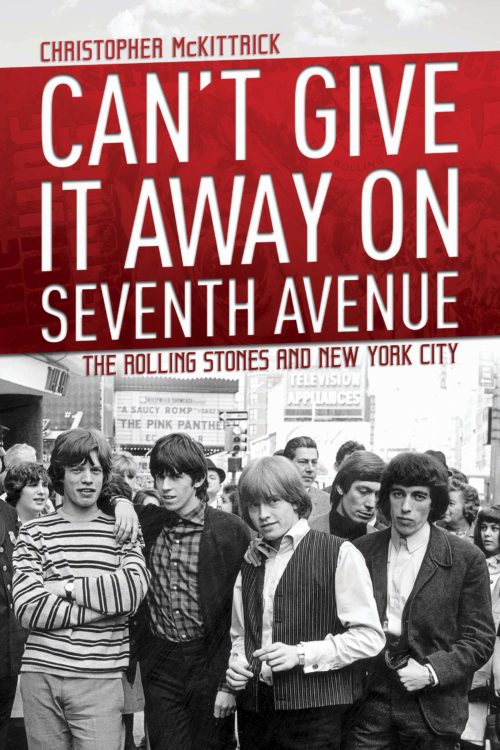

In this exclusive extract from ‘Can’t Give It Away on Seventh Avenue: The Rolling Stones and New York City’ by Christopher McKittrick we can see the history of the Stones through the prism of New York.

This detailed book documents the dynamic and reciprocal relationship between the world’s most famous band and America’s most famous city as well as being an absorbing chronicle of the remarkable impact the city has had on the band’s music and career.

Prologue

On October 20, 2001, Mick Jagger walked onto the stage at Madison Square Garden—an arena he had performed in as the lead singer of the Rolling Stones eighteen times over the previous thirty-two years. By then “The World’s Most Famous Arena” had already played an instrumental role in the legacy of the band. All but one of the songs on their landmark live album ‘Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!’ The Rolling Stones in Concert were recorded during their first concerts there in November 1969, and clips from the same shows were featured in Gimme Shelter, the infamous 1970 documentary. Signifying the band’s long history with the Garden, in June 1984 the Stones became the first rock group to be inducted into the venue’s Hall of Fame.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V_yaQbWR6xc

Jagger, however, was not appearing that night with the band he had fronted since 1962. He had not played with the Stones in over two years, since the conclusion of their No Security Tour. In the months prior, he had been recording and doing preliminary promotional work for his fourth solo album, Goddess in the Doorway, which was set to be released in November, but on this night, Jagger was one of the many famous musicians participating in The Concert for New York City, a benefit show in memory of the nearly three thousand New Yorkers who had been killed in the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center less than six weeks earlier.

Jagger wasn’t alone. Keith Richards, his childhood friend and the Stones’ guitarist, appeared unannounced at the side of his longtime bandmate, and the “Glimmer Twins” were showered with cheers from an audience made up mostly of hundreds of members of the New York City Fire Department, the New York City Police Department, and their families. After they embraced each other, Richards stepped up to the microphone while strumming his guitar.

“New York. How ya doing, guys? You know, I got a feeling this town’s gonna make it.”

Coming from the mouth of the quintessential rock ’n’ roll survivor — few rockers have been as up close and personal with death as Richards — it was a proclamation of endurance and hope. Richards, Jagger, and the house band then launched into an uplifting rendition of “Salt of the Earth,” the rarely performed but poignantly appropriate gospel-influenced final track on Beggars Banquet.

Before sliding into the next song — the disco-influenced “Miss You,” which celebrates the dirty decadence of ’70s Manhattan — Jagger offered his own proclamation on the enduring spirit of New York City: “You know, if there’s one thing to be learned from this, if there’s one thing to be learned from this whole experience, it’s you don’t fuck with New York, okay?”

Though Jagger and Richards were born almost six decades earlier, an ocean away in Dartford, England, the pair were speaking on good authority. Besides their intimate history with Madison Square Garden, both Jagger and Richards called New York City home for many years. Despite their English origin, the Rolling Stones can be considered one of the great New York City bands based on their long, colorful history with Gotham in their music, performances, and offstage antics. The band’s emotional connection with the city spans decades. A year after the attacks, Jagger allowed a song from Goddess in the Doorway titled “Joy” to be used free of charge in a commercial made by the City of New York to thank the rest of country for their aid in the aftermath of the attacks.

When the Rolling Stones began gigging around London in the early 1960s, it was impossible for them to know that their music would take them all over the world many times over for more than five decades. When Jagger and Richards had the fateful chance reunion at the Dart-ford railway station in 1960 that would eventually alter the course of rock music, neither could have imagined that they would both make New York City their home and that Manhattan would become ingrained in the music and image that their band would create.

Before the 1960s, popular music was rarely globe-spanning, and when the Rolling Stones was formed, English rock ’n’ roll bands certainly did not have that reach. While the Stones were devoted fans of American rhythm and blues and rock and roll, British bands that emulated their sound played London and, if they were lucky, perhaps as far as West Germany. At that time the transatlantic pop music exchange from the United States to the United Kingdom was almost exclusively one way, which explains the fascination British Invasion bands had with American music. British pop music fans could easily find their favorite American artists at the local record store, but Americans had yet to show much interest in British artists.

Outside of making a handful of appearances on popular US TV programs, as Lonnie Donegan did on The Perry Como Show and The Paul Winchell Show in the mid-1950s, followed by his tour of the States in 1956, it was unprecedented for British bands to have sustained success in the United States. Rocker Cliff Richard, popularly regarded as the “British Elvis,” did a four-week US and Canadian tour in January and February 1960 and a second tour in August 1962, but he failed to make a major impact. In contrast, American artists toured England with great success. In fact, the Stones supported Bo Diddley, Little Richard, and the Everly Brothers on a fall 1963 UK tour and would later open for New York City natives the Ronettes on their January 1964 UK tour. After all, the United States already had Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, and Muddy Waters. Why would America ever demand English imitations? “When I was growing up, the idea of leaving England was pretty much remote,” Richards wrote in his 2010 autobiography, Life. “My dad did it once, but that was in the army to go to Normandy and get his leg blown off. The idea was totally impossible.”

At first, New York did not hold the same promise for the young Jagger, Richards, and Brian Jones as another American city. Their love of the blues and Chess Records put Chicago higher on their list of American cities to visit. Though New York is the home of the Brill Build-ing, which was still the center of songwriting and business in American pop music in the early 1960s, all of Jagger and Richards’s idols had recorded at Chess Studios in Chicago. It’s no surprise that during their first American tour they recorded a few songs at Chess and met Muddy Waters, Chuck Berry, Willie Dixon, and Buddy Guy on the premises. Though the Stones would develop a strong connection with Chicago, in subsequent decades the group would plant stronger roots in New York City and draw influence from the music of 1970s Manhattan.

Of all the Stones, drummer Charlie Watts, who formally joined the group in January 1963, was perhaps the only member who had designs on New York at a young age. Watts had grown up a fan of jazz and had played in numerous jazz clubs in London with local bands. He was devoted to American jazz greats and as a teenager even wrote and illustrated a picture book, Ode to a Highflying Bird, as a tribute to Char-lie Parker. It was published in 1964. Decades later, Watts recalled his early ambitions to The Guardian. “I wanted to be Max Roach or Kenny Clarke playing in New York with Charlie Parker in the front line. Not a bad aspiration. It actually meant a lot of bloody playing, a lot of work. I don’t think kids are interested in that. But that may be true of every generation, I don’t know. When I was what you’d call a young musician, jazz was very fashionable.” By the time Watts joined the Stones, they were already performing bluesman Jimmy Reed’s “Going to New York” in their set, though Watts might have been the only one who believed the song’s title. Watts’s Manhattan jazz club dreams would eventually come true, but only after the Stones became the toast of the city.

It was appropriate then that when the Stones made their first visit to the United States, they arrived in New York, landing at the recently renamed John F. Kennedy International Airport on June 1, 1964. It was less than four months after the Beatles’ hugely success-ful tour, which featured iconic performances on The Ed Sullivan Show and ignited Beatlemania in America. Despite their perceived rivalry, in June 1964 the Rolling Stones were no Beatles. Their first American album, England’s Newest Hit Makers, was released only two days before their arrival, and their first US single, a cover of Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away,” had been released in March in the wake of the Beatles’ US debut but failed to make a major splash (reaching only number forty-eight on the Billboard chart). During the tour, their second US single “Tell Me” was released on June 13 and peaked at number twenty-four. Whereas the Beatles came to the US as conquering heroes with “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and “She Loves You” at the top of the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart and Meet the Beatles! and Introducing…The Beatles at the top of the Billboard albums chart, the Stones were unestablished underdogs. They arrived largely unheralded and departed three weeks later hardly better known.

Yet, on the touring front, the Stones would eventually have a far bigger impact than the Beatles. While the Beatles were truly the first globetrotting pop band, they ceased touring after August 1966. The Stones were just getting started, and their best tours, and in particular, their best concerts in New York, were still ahead of them. After following the Beatles in playing Carnegie Hall, The Ed Sullivan Show, and Forest Hills Stadium in the mid-1960s, the Stones would go on to play every major venue in the New York metro area on their box office record-setting tours—including stadium shows in Queens and East Rutherford, New Jersey, arenas in Manhattan and Brooklyn, and theaters and orchestra halls all over Manhattan. The number of stages the members of the Stones have appeared on in New York more than doubles when the members’ solo concerts (including the pre-Stones groups of Ronnie Wood and both the pre- and post-Stones groups of Mick Taylor) are taken into account. Counting the number of times a member of the Stones jammed with another artist on a Manhattan stage, particularly in the late ’70s and early ’80s, there is more Stones history in New York than in any other city in the world. It’s no surprise that when the Stones announced the initial dates of their fiftieth anniversary tour, two were at London’s O2 arena and three were in the New York metro area. London might have given birth to the group, but it was in America, and in New York City in particular, where they truly developed into “The World’s Greatest Rock ’n’ Roll Band.”

Indeed, much had changed already for the Stones by the time they arrived in New York for their second American tour on October 23, 1964. Their second US album, 12 x 5, was released six days earlier and quickly rose to number three on the Billboard charts. The original version of “Time Is on My Side” had been released as a single on September 26 and became the group’s first American top-ten hit, reaching number six on the Billboard singles chart. They would play the song along with Chuck Berry’s “Around and Around” on The Ed Sullivan Show on October 25, the first of a half-dozen appearances the band would make on the career-making program. Much like the Beatles earlier in the year, the Stones’ performance was answered by an audience full of girls screaming hysterically, especially when Jagger, dressed casually in a sweater instead of a suit like the Mop Tops, bobbed and weaved during the guitar breaks. America was hooked, and each of the Stones’ subsequent studio albums, from 1965’s The Rolling Stones, Now! through 2016’s Blue & Lonesome, would reach the top five on the Bill-board charts. Fans never stopped screaming for the Stones, especially in New York.

While the Beatles’ pop sensibilities remained firmly British despite their early covers of American songs like “Twist and Shout,” it was the Stones who more deeply mined American music—blues, rock, country, and even bits of the Great American Songbook—for their sound. As Richards said to The New York Times in 2002, “I think that’s the difference between us and the Beatles. They were much more homegrown. We were always looking out. It was the difference between Liverpool, which to a Londoner is very provincial, and London, where we came from.”

Though the Stones would remain based in England through the end of the 1960s, their connection with New York City would grow each time they returned to the United States for a tour. Starting in late 1965, Brian Jones made several visits to Manhattan until his final one in September 1967. Jagger and Richards would both spend an increasing amount of time in the city, particularly when Jagger became well established in celebrity social circles during the 1972 American Tour. By the late 1970s, Jagger, Richards, and the newest Stones guitarist, Ronnie Wood, all had residences in Manhattan and were common fixtures at nightclubs and social events. Former Stones guitarist Mick Taylor, who played with the group from 1969 to 1974, would begin regularly playing in New York and the metro area in the mid-1980s, and Watts would finally get to embrace his big-band jazz club aspirations by bringing the Charlie Watts Orchestra and his succeeding solo bands to New York starting in 1986. Even bassist Bill Wyman, who officially retired from the Stones in 1993, would return to New York in 2001 to play a concert with his solo band, the Rhythm Kings. In addition to the band’s extensive performance history in New York as a whole, New York City is the only city in which every member of the Rolling Stones has played shows with side projects (with the exception of Jones, who never had a solo band). Not even London, the birthplace of the Stones, can claim the same.

As with everything with the Rolling Stones, the band’s history in New York City is entwined with some of the most infamous stories of rock ’n’ roll decadence. When the Stones first arrived in New York, it was a city in decline. The 1960s and 1970s brought immense social change to New York, much of which was reflected in the Stones’ music. During the 1970s and early 1980s, the Stones’ changing sound was influenced by the new music of New York City’s nightlife, economy, and culture. In the years leading to the twenty-first century, New York City’s booming economy paralleled the band’s monstrously successful concert tours in the 1990s and 2000s, which fundamentally changed the music business. In an art form where artists are frequently decried by their fans for “selling out,” the Stones continue to write the book on marketing a band as a business entity, and have almost inexplicably gained even more popularity and financial rewards to a degree previously unimaginable by pop musicians.

Richards knew that New York City would “make it” after 9/11 simply because it was the city that made the Rolling Stones the wildest, sleaziest, and most exciting rock band in history. While New York can claim dozens of homegrown artists born and bred to sing of the streets and the subways, no band quite matches the spectacle of “The Capital of the World” like “The World’s Greatest Rock ’n’ Roll Band.”

‘Can’t Give It Away on Seventh Avenue: The Rolling Stones and New York City’ is available from Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and Books-a-Million.

About the Author

Christopher McKittrick’s publications include five entries in 100 Entertainers Who Changed America (Greenwood) and “The Secret History of New York Blues” in Artefact magazine. Christopher and his work have been quoted in The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Newsday, and CNBC.com. See also @7thAveStones

Copyright © Christopher McKittrick, 2019. All Rights Reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the author.