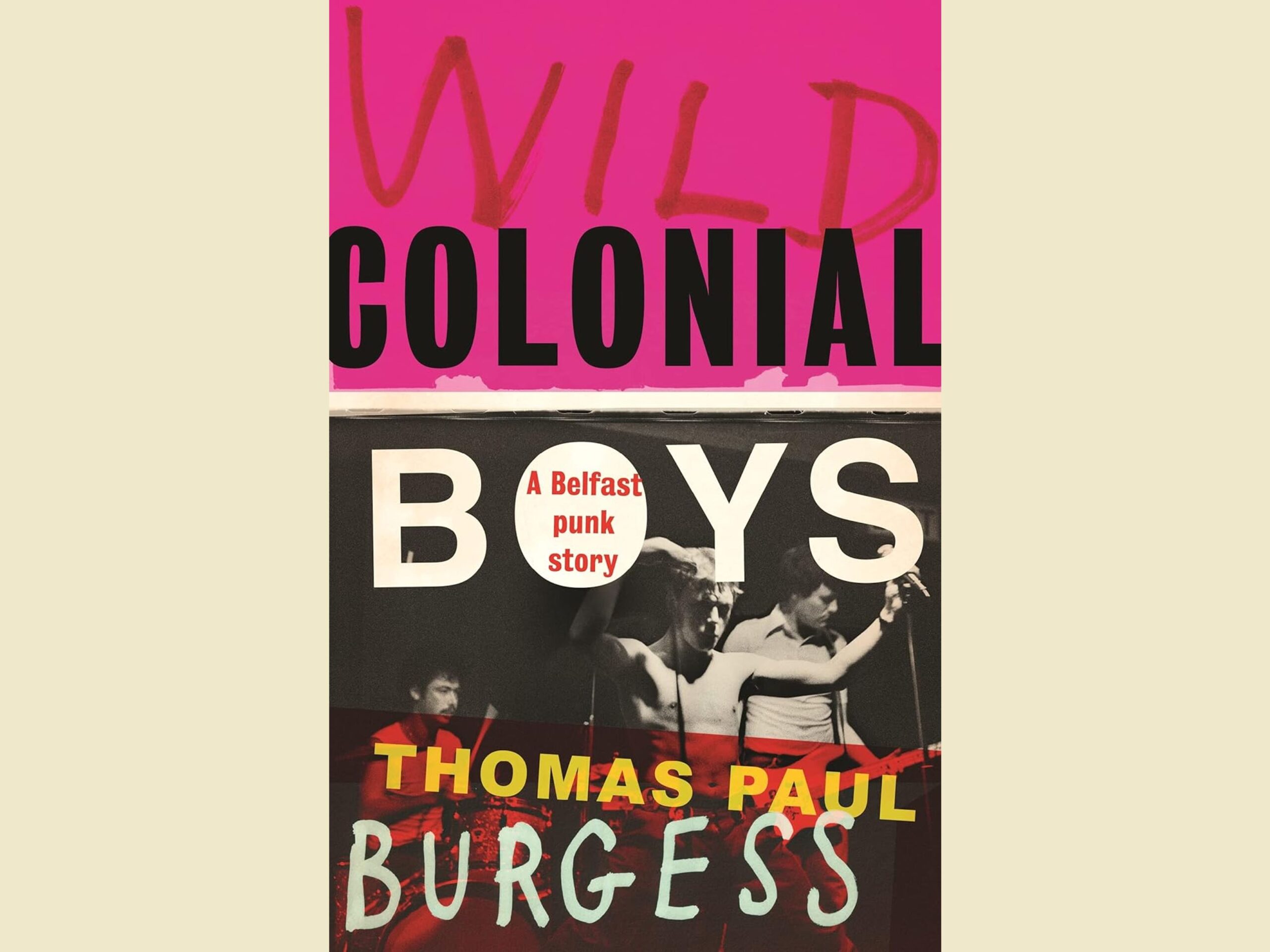

Thomas Paul Burgess talks to Jason Barnard about his life and memoir, ‘Wild Colonial Boys: A Belfast Punk Story.’ The memoir serves not only as a recounting of Northern Irish punks Ruefrex’s turbulent trajectory but as a fearless exploration of identity, class, and the political landscape that shaped the band’s fervent protest through music.

Writing a memoir is a significant undertaking. What prompted you to write ‘Wild Colonial Boys’ and how did you approach the writing process? You have a background in academia, did your academic background influence how you wrote it?

The motivation for writing ‘Wild Colonial Boys’ was straightforward enough. I have to some degree, long harboured a sense of injustice that the narrative representing this period – owned and manipulated as it is by a few key cultural gatekeepers- largely erased my band, Ruefrex, out of the picture. And they did so for questionable motives regarding politics and cultural identity. Much has been made of the Terri Hooley/Good Vibrations version of events, represented as they are by a Hollywood movie and now a Broadway musical. I believe the story related in my book, offers a more accurate, authentic and compelling account of that period.

I found the prospect of writing a memoir/autobiography genuinely daunting. For all the obvious reasons of course; the exposure of personal revelations and the trepidation regarding giving offence both to friends and adversaries alike! As an academic, I have of course published scholarly books , articles and treatises, where scrupulous objectivity is required. (The very antithesis of a memoir!) My academic training did help in correlating and compiling information (some of it from quite a long time ago now). However, I was conscious that my publisher, Manchester University Press, were pitching the book at the ‘Trade’ sector. So I was careful to avoid language that would stylistically render the book dry or stilted. I also wanted the chapters to be concise and accessible, (and I explain this in the preface). Additionally, as a novelist, I had my story to tell. And I believe it to be a good story, well told. That’s all, in the final analysis, I could hope for. But one can dream! Netflix commissioned ‘Derry Girls’. Why not, ‘Wild Colonial Boys’!

Can you share how the band emerged from the Belfast street-gang culture of the late-1970s? What inspired you to form a band during such a turbulent time?

I have said elsewhere that – while aspects of our street gang persona as ‘The Debonairs’ (or Debs), were unpalatable and often regrettable – they nevertheless ‘protected’ us from the dangers of aligning with those youths (just a few years older) who carried out unspeakable actions on behalf on the paramilitaries groups. At fourteen and fifteen year olds, this meant that our rites of passage in that most challenging of environments, were somehow cocooned from the horrors going on around us. We had our own collective, with strict rules of conduct, dress code and we harboured a healthy cynicism toward paramilitary organisations. Most importantly…we had our music. It was a defining badge of honour, an indication of whether or not you could be trusted. Something to enthuse about, to escape into, to belong to. A club where all you needed to know about someone was whether they liked David Bowie, Lou Reed, Alice Cooper. And then of course, we had Punk Rock. The ‘DIY’ ethos behind this and the politics at the heart of it, convinced me that I could have a voice. It’s difficult to convey that teenage energy, that excitement, the affirmation of that time. It was a cause, one that no one had to die for, a perfect storm of rebellion, belonging and purpose where none had existed before. I believe this unique set of circumstances is the reason why punk rock meant more to youth in Belfast than in any other city in Britain or Ireland.

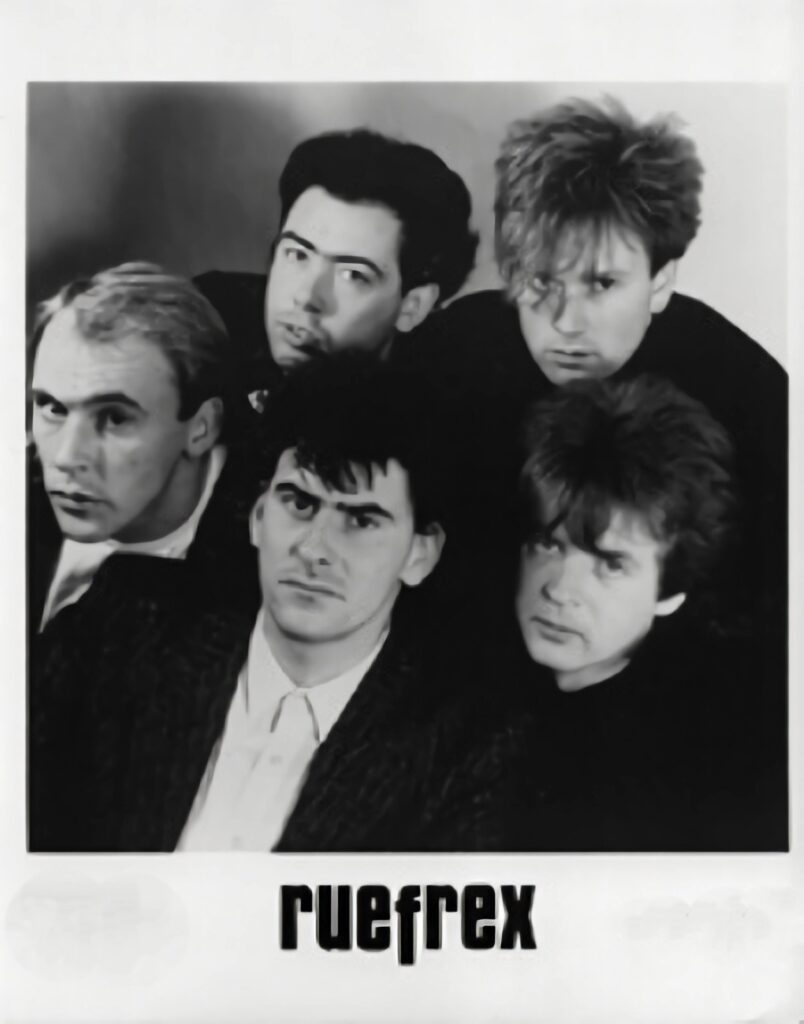

Ruefrex went on to achieve commercial and critical success. Can you walk us through the band’s journey, from its early days to wider achievements?

Ruefrex effectively had two visits to the well. Seven minutes, thirty seconds of fame each time if you will! Firstly, as callow youths in our late teens and early 20’s, we enjoyed some success off the back of our first single, ‘One by One’ on Good Vibrations Records. This was augmented by some decent coverage in the national music press (most notably the NME) and regular plays from John Peel on BBC Radio one. Our live show was attracting considerable interest but was mostly limited to Irish venues. High profile support slots (with Stiff Little Fingers) and a BBC documentary about the band entitled ‘Cross the Line’, also helped. Subsequent singles, ‘Capital letters’ and ‘Paid in Kind’ on indie labels, kept us in the public eye. The band at this point took a sabbatical of sorts, with members – somewhat disillusioned -pursuing gainful employment, relationships and the like. (I left my job and went to University). However, things were kick-started again, in a most unexpected way, with the success of the ‘Wild Colonial Boy’ single. This led to a considerable increase in press and label interest, culminating in moving to London, signing with Stiff Records and releasing our first album, ‘Flowers for All Occasions’.

‘The Wild Colonial Boy’ was a controversial release that tackled American donations to Northern Irish terrorist organisations. Can you discuss the motivations behind recording the song and the reactions it received? What was it like playing it live on The Tube?

Martin J. Galvin was an Irish American lawyer and activist notable for his role in the formation and promotion of NORAID (the Irish Northern Aid Committee). The organisation became known for raising funds for the Provisional IRA and other nationalist groups during the Troubles. Although banned from Northern Ireland for espousing terrorism, Galvin entered the country in 1984, attending high-profile gatherings, flouting his presence to the security forces and providing Sinn Féin with a press coup.

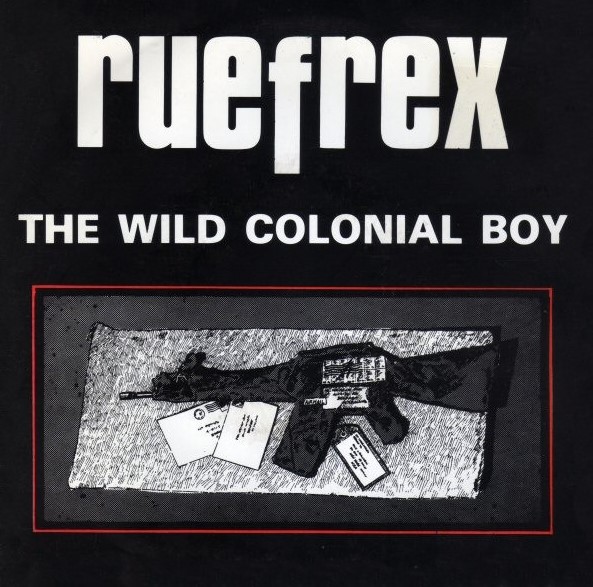

This flurry of activity provided the catalyst for Ruefrex to record and release a song that we’d finished a year earlier and that had become a staple of our set. ‘The Wild Colonial Boy’ borrowed its title from the well-known Irish ballad of the same name. A favourite of Irish exiles the world over, it tells the story of Jack Duggan, an Irish rebel and native of Castlemaine, County Kerry, who became a convict, then a bushranger in nineteenth-century Australia.

The title is where the similarity ends, though. I wrote the narrative from the perspective of an Irish American, residing in Wisconsin, who is providing funds for IRA terrorism. The song has him ruminating that ‘…it really gives me quite a thrill to kill from far away’, and accuses Irish Americans of perpetuating Irish stereotypes of British oppression while hypocritically mistreating the African American population. I was influenced by Randy Newman’s ‘Rednecks’ which takes the perspective of a southern racist. Irish people everywhere would undoubtedly balk at a song with the line ‘I know that if I get my chance, that I can jig and reel and dance, cuz in between the killing, that’s what all us Irish do’. The finer points of employing a ‘false narrator’ would be lost on them, and there was a real danger of gross misinterpretation and misrepresentation.

It was clearly our best song, based on feedback from live performances, and also our most pertinent for the time and place in which we found ourselves. If one song could quintessentially represent the band, this was it. We simply had to get it out there before admitting defeat and leaving the stage forever.

We scraped some money together and called in a few favours in order to secure recording time. I was determined that the message of the song wouldn’t be lost. So I commissioned artwork featuring a drawing of an Armalite AR-18 rifle wrapped in brown paper and string, festooned with postage stamps and lying on a doormat, as if it had just been delivered in the mail. On the reverse was to be the song lyrics.

In short, we would be committing commercial and political suicide with this release, and it was unlikely that any mainstream broadcaster would touch it with two bargepoles tied together! Not that any of this overly mattered to us. It hadn’t done up to that point, so why begin now? At least we would be in absolutely no doubt that our message would be out there, undiluted and undiminished, right in their fucking faces. It was to be a last beautiful act of self- immolation. To my complete amazement, ‘The Wild Colonial Boy’ picked up daytime Radio One play, reached No. 30 in the UK charts, sandwiched between Bruce Springsteen and Sister Sledge, and the telephone started to ring … and ring … and ring.

Performing it on The Tube evoked mixed emotions. The sound mix on The Tube was often notoriously poor, giving everything a curious quality – particularly guitars – of having been ‘phased’ (electronically washed to produce a bland consistency). So it was evident that the film and sound crews had to be finessed. After all, they were responsible for making you look and sound good in front of millions of viewers. We were to perform two songs: ‘The Wild Colonial Boy’ and ‘The Ruah’, the latter chosen because it featured acoustic guitar, and we wanted to let everyone know we had a greater range than your average rock outfit.

The floor manager was especially insistent that, during the live broadcast, we should keep to the areas we had occupied in rehearsal. This, he explained, was to ensure the best camera angles.

A fraught, seemingly endless period of waiting followed during which we sat in our dressing room, we bickered, smoked, bit our nails to the quick, peed with abnormal frequency. Eventually we were called.

Immediately, our singer, Clarkey deviated from his agreed stage routine, climbing on the drum riser and launching himself into the air. Coursing adrenaline drove us to speed through the performance at a faster pace than intended. All the while, our singer prowled the stage’s edge, fashioning his mic stand into a gunsight and generally terrifying individuals in the crowd, and careering across the stage, causing the handheld cameramen to bump off scenery and catch each other in shot (something they deplored as it made them appear amateurish). Suffice to say, it was not all I had hoped it would be.

Ruefrex’s music is often noted for its candid and outspoken nature, addressing political and societal issues. How do you view the importance of the lyrics in your band’s catalogue?

As the band’s sole lyricist, it was always my intention that the words would be front and centre of our project. (Much in the way that my heroes ‘The Clash’ had done.) I very much viewed the songs as a platform or soap-box by which to address the issues of social injustice, class politics and of course, the situation in Northern Ireland. You might think that such political sensibilities would be ridiculed by the pogoing, gobbing punks of the Harp Bar, but in my experience, punters who loved The Clash and The Pistols placed considerable emphasis on ‘the message’ of our songs. Some bands wrote about ‘chocolate and girls’, as The Undertones, in their brilliantly perverse and contrarian manner, claimed. But Ruefrex were unashamedly political in outlook and expression, and we made no apology for this. In short, the lyrics were everything to me.

Are there any particular Ruefrex tracks that are favourites and why?

An early, alternative, off-the-wall song, ‘Don’t Panic’ (in a Siberian climate, cuz the pendulum swings both ways)’ holds a place in my heart! It abandoned any traditional four-four time or verse-chorus sequence, using instead a staccato guitar stab backed by a low rumbling bass and ‘mummy-daddy’ beat played out on the toms. Just when it might have become repetitive, the song exploded into a fast middle-eight section. The lyrics were a jumble of alliteration, suitably surreal to complement the essential oddness of the track. The song could easily have sat on the Pink Flag album by Wire. We had inadvertently recorded a homage to one of our favourite bands, although it was not our intention at the time.

‘The Wild Colonial Boy’ of course, because I think it most perfectly and characteristically evokes what the band were all about. And of the political/protests songs, it is perhaps the most realised as a contemptuous denunciation.

Another, lesser known song , that I believe is powerfully realised, is ‘On Kingsmills Road’. It appears on the ‘Political Wings ‘ EP and is a self-penned ballad recounting a particularly detestable episode in the history of the Troubles when the Provisional IRA murdered ten workmen in a sectarian attack in South Armagh.

Not all our songs have overtly political intent however and I enjoyed performing ‘Even in the Dark Hours’, essentially an unapologetic rock ballad of lost love. ( Bizarrely, ‘Even in the Dark Hours’ was recorded and released by Page 3 model Samantha Fox in 1987 under the title ‘Even in the Darkest Hours’). At the other end of the Ruefrex spectrum is ‘In the Traps’, which unashamedly played to our power-pop sensibilities. There are some great hooks in there! The lyric was a scathing indictment of the limitations of an elitist educational system.

What are your memories of touring with Shane MacGowan and The Pogues?

When I first met the late Shane MacGowan, there was little evidence of the individual who would become the beloved icon of Irish culture we know today, lauded for his songwriting abilities and artistic contributions to the canon. I always found him personable and self-effacing. While the other band members might gather in rowdy communion, when in his cups, Shane liked nothing better than to find a quieter corner to settle in alone with his drink. And his intake was indeed prodigious! (I recorded a homage to him some years later, with my current band, ‘Sacred Heart of Bontempi’, entitled ‘Shane MacGowan’s Smile’. It recounts an early morning liquid breakfast whilst we were both appearing on Ireland’s national broadcaster, RTE.

It was another few months before we met again, this time backstage before our support slot to The Pogues in Portsmouth. We had witnessed hijinks aplenty on this short tour, both behind the scenes and during the gigs, but Portsmouth was a new low. Students, shore-leave sailors, and locals beat the shite out of each other in spectacular fashion, while the band(s) played on.

Shane’s reputation for hard drinking was legendary from the outset and the band’s live concerts were often raucous, stage-diving, celebrations of excess. Their musical hard edges were smoothed by the talented songwriter and guitarist the late Phil Chevron, previously of Dublin band Radiators from Space. A thoughtful and astute individual, it was Phil who turned up as representative from The Pogues to share an interview with me for one of the big London independent radio stations.

The focus inevitably turned to Irish politics, and while this was a topic I had become adept at fielding, I was wary of a pro Provos stance from a band whose membership and followers made no secret of their uber republican credentials and politics. So I was both relieved and surprised when Phil offered a balanced, nuanced and considered take on the then situation in Ireland. This was a rare enough perspective within the music business, where anti-Thatcher sentiment equated with Irish nationalism and ‘the struggle for liberation’. But for a member of The Pogues to resist these lazy oversimplifications … well, I was impressed. The same could not be said, however, of some of the other band members or the entourage that travelled with them, and this became all too evident as time went on.

Your recall encounters with notable figures such as U2, The Cure, The Fall and Seamus Heaney? Can you share a memorable interaction or experience with some of these individuals?

Well…I have to hold some stuff back or no-one will buy the book! Perhaps I could recount an encounter with a certain singer who currently holds a residency in Las Vegas!

Way back in the day, when we were first starting out (I’d say around 1978-79) , a support act at the time, ‘Ask Mother’, (an art-rock outfit that had jumped on the punk bandwagon), had somehow misplaced their drummer and they wondered if I’d like to sit in with them for their set in Dandelion Market, Dublin. The bohemian buzz around the market seemed a million miles away from the open wound of urban decay and raw violence associated with Belfast at that time. Vintage clothing, accessories, furniture, music. It was also where you could find buskers entertaining shoppers as they browsed the stalls.

A little unsteady on my feet (for we had been smoking weed and drinking on the journey down), I negotiated a slow pace through the crush of punks, hippies, punters and tourists until I felt a hand on my shoulder. I turned around but could see no one in my immediate line of sight.

‘You’re Paul Burgess, right?’ said someone with a Dublin accent.

I looked down. A shortish guy, sporting a bad mullet, leather trousers and a wide grin seemed pleased to see me. I was searching my memory for a name but was fairly sure I didn’t know any Dubliners. I played for time.

‘Don’t tell me … I owe you money, right?’

It was a weak rejoinder and, believing it to be self-deprecating and witty, one I employed on the very rare occasions when I was treated like a minor celebrity by someone who had liked our single.

He was still grinning. ‘Paul Burgess from Ruefrex. I heard your record on the John Peel Show … on the BBC.’

‘That’s great! Thanks!’ Unused to this kind of interest from strangers, I was genuinely disarmed by the attention.

I looked over my shoulder to see the others walk off into the distance, being swallowed up by the crowds. I hadn’t a clue about Dublin or where we’d left the van and I made to follow them.

The hand was on my shoulder again. ‘I have the record … “One by One”… love it!’

‘Brilliant … listen, I need to catch up with my mates …’

The hand stayed on my shoulder. For the first time, I noticed his blue eyes – the intensity, the earnestness, the urgency, the burning need to share something he clearly deemed of huge importance.

‘I’m in a band,’ he announced. ‘We’re playing here today!’

There it was. ‘Oh yeah … what are you called then?’

He squeezed my shoulder hard, locked on my eyes and with an almost devout vocation said, ‘U2 … we’re called U2.’

I dined out on the Dandelion Market story for years afterwards, rather churlishly boasting that Bono had more records of my band than I did of his (untrue, as Achtung Baby is an unadulterated classic). But now when I think back on that day, I see how we were both playing out a scene in which – unbeknownst to both of us, of course – our roles were to be utterly reversed. I would go back to my job in the aircraft factory and he would go on to London, ultimately to be signed by Chris Blackwell and Island Records. The rest, as they say, is history.

Punk could do that – make everyone a star and a fan at the same time.

How did you ensure that Ruefrex remained faithful to working-class origins throughout the band’s turbulent and decade-long career?

My own early experience was marked by humble beginnings. In 1971 I had been living in a two-up two-down in Jersey Street, Shankill Road. No hot water or central heating; a tin bath in front of the fire for ablutions; an outside toilet; a small bedroom shared with my older brother. Perhaps not surprisingly, this went some way to informing my subsequent views on matters of class equality and social justice and shaping the left-of-centre politics that would permeate my career and creative endeavours thereafter.

In some respects, I’m something of an unlikely poster boy for the meritocratic system and social mobility! A failed 11 Plus student from a troubled Belfast comprehensive, I was threatened with expulsion for running with ‘the wrong crowd’ and recall my schooldays as a catalogue of clashes with authority punctuated with occasional threats from paramilitary bullies. I was abandoned to the dead zone of the dreaded CSE class, while learning a language was replaced by Technical Drawing and History and Economics were replaced by Woodwork and Metalwork. It seemed I was destined for an ill-suited apprenticeship in a city where traditional industries were in terminal decline. However, through a succession of government grants (now long gone), single-mindedness and opportunism, I somehow managed to secure a Masters and PhD from Oxford University (It’s a long story!)

Running parallel with this of course, was the band’s attempts to storm the citadel of the UK music industry. The one consistent thread running through all of this was an unshakable belief in my own class identity and politics. The other members of the band shared this background, were defined by it and drew upon it as an important ‘grounding’ throughout various periods of pressure and uncertainty.

Every band faces challenges. Can you share a particularly challenging moment for Ruefrex and how the band overcame it?

Playing politically themed songs in the Belfast of the 70’s and 80’s could be a dicey business! Young men our age were being shot on a daily basis. The Harp Bar in Hill Street, Belfast, was a dingy, heavily fortified pub in a dimly lit, narrow, cobblestone street in a run-down part of the city. Frequented by dockers, horse racing punters and winos, it was an unlikely venue to establish itself as the mecca for punk in the city. Despite the popular myth that the Harp offered an open-armed, no-questions-asked sanctuary for punks seeking to escape the sectarian divisions of the city, that was not always the case. The pub had a reputation for its hard-drinking, hard-living clientele who did not suffer fools gladly. The politics of the management, bar and door staff was predominately nationalist, likely with a socialist/Official IRA leaning.

We were rounding off a solid Friday night set and were on to our encore. The floor in front of the stage was awash with writhing, pogoing, body-slamming punks. For the encore we had chosen to cover Sham 69’s ‘Ulster Boy’. We weren’t particularly fans of Jimmy Pursey, his band or his cockney sensibilities, but the lyrics (inane as they are) are about our patch. If you know the song, there is a repeated refrain of ‘Ulster … Ulster …’, delivered with chant-like, air-punching monotony and easily comparable with popular Loyalist songs. I would be lying if I said that the ambiguity did not appeal to some sense of mischief on our part.

During the performance I noticed an urgent confab taking place amongst some huddled figures at the back of the room. a small, heavy-set man in his mid-fifties wearing a suit and open-neck shirt approached the stage front, smiling and nodding as he made his way through the crowd. But his expression changed to a scowl as he came to the lip of the stage. With his back to the crowd, he unbuttoned his jacket and held it wide open to reveal the butt of a semi-automatic pistol stuffed into the waistband of his trousers.

‘Play one more note and yer fuckin’ dead men!’ he growled.

We looked at him in shock. We’d heard of nothing like this in the Harp before. It was as if we had overstepped some invisible line and our punk rock protections had been revoked, with extreme prejudice.

‘Pack up yer gear and get the fuck out of here … NOW!’

This we did.

But shaken as we were, in no way did we allow this to deter us from our anti-sectarian ‘mission’. And within days, we were playing a fund-raiser for religiously integrated schooling and publicly pledging to play working class community centres in Nationalist/Republican heart-lands (which we did).

Looking back on Ruefrex’s legacy, how do you think the band contributed to the punk scene in Northern Ireland, and what impact do you believe it had on subsequent generations of musicians?

Our gigs were always notable for the many members of other bands in attendance. We knew they were there to see what we were up to with new material, rather than out of any sense of unambiguous fandom. Nevertheless, we liked to believe that we commanded respect from our peers – for our songs, our performance or maybe even our uncompromising musical and political integrity.

I have mentioned elsewhere that certain cultural gatekeepers on the Irish music scene gave Ruefrex little or no credit or recognition for our successes. This became particularly spiteful when, in later years, Ruefrex were effectively written out of the Good Vibes history by a small cabal of devotees, well placed in broadcasting, film making and journalism. For us, our enduring antipathy toward the Good Vibrations myth was about the lack of love and respect shown to the band. But as any artist will tell you, it is the opinion of the fans and not the critics, that ultimately holds sway. I’m always heartened by the hard-core of fans who have remained unswerving in their support and love for Ruefrex and what we tried to achieve in challenging the scourge of sectarianism. The affirmation that comes from young bands covering our songs or name-checking us as a seminal influence; the approaches from researchers and scholars, seeking to learn more about the our particular brand of Punk Rock protest; or simply the warm, nostalgic reminiscences of those still around, who fought shoulder to shoulder with us in the Punk Rock wars. These are the things that ultimately make it all worthwhile.

Further information

‘Wild colonial boys: A Belfast punk story’ by Thomas Paul Burgess is published by Manchester University Press