Wolfman Jack, American Graffiti

Scott Shea unearths the howls, hustles, and high-voltage mythmaking of Wolfman Jack, the gravel-throated alchemist who turned AM radio into a late-night fever dream. With a fan’s passion and a historian’s stubbornness, Shea traces the Wolfman’s wild ride from Brooklyn basements to Mexican border blasters to Hollywood immortality, laying out a tale of teenage gangs, backroom deals, FCC dodges, and pop-cultural reinvention.

The Wolfman Is Everywhere: The Incredibly True Story of the Rise of Wolfman Jack

In Search of…

To me, it’s one of the greatest cinematic moments of all time. Near the final act of the 1973 George Lucas film “American Graffiti,” the character of Curt Henderson, played by Richard Dreyfuss and the chief protagonist of four main characters, wanders into an isolated radio station on the outskirts of his California hometown. All night long, he’d been chasing after a gorgeous, mysterious blonde, played by Suzanne Somers, who mouthed “I love you” to him from her 1956 Ford Thunderbird while stopped at a traffic light. Through circumstances, he learns that Wolfman Jack, the mysterious XERB DJ who plays in the background throughout the movie, broadcasts his show from there and ventures out to enlist his help with a dedication. He wanders into the station in the wee hours of the morning and encounters a bearded man who invites him to his broadcast studio.

“Are you the Wolfman?” Curt asks excitedly.

With a chuckle, and to Curt’s disappointment, the unnamed man tells him that he is not. He’s just one of his employees. Curt’s problem is he’s heading out to college in a few hours, and he desperately wants to meet this woman. He listens to Curt’s story and ends their short time together by promising to convey the dedication to Wolfman Jack and get it on the air as soon as possible. As he’s walking out, he hears the voice of the Wolfman talking up the next record and notices it’s coming from the man with whom he’d been talking. He lightly chuckles and then leaves the station.

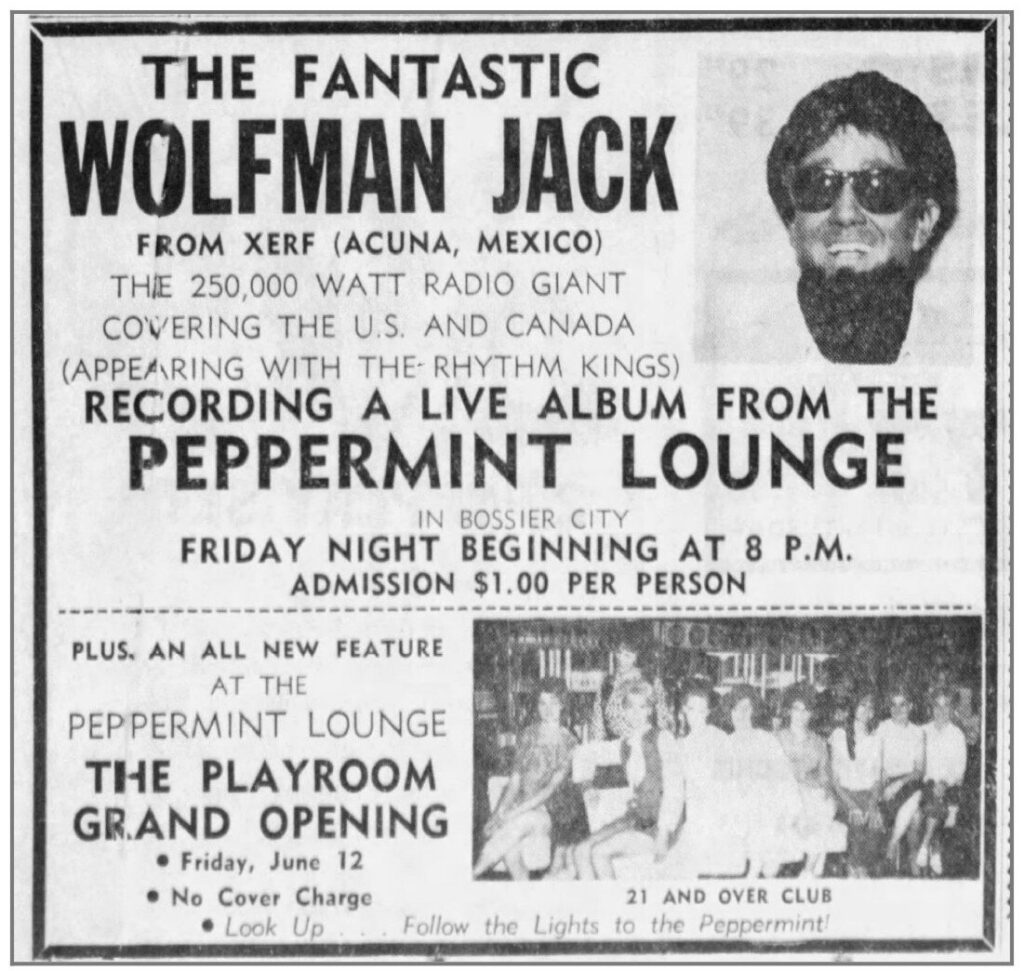

It’s not action-packed like the Godfather baptism scene or highly dramatic like Darth Vader telling Luke Skywalker that he is his father. Rather, it’s tender, poignant and a bittersweet coming of age moment filmed in one short scene. Back in 1973, this event was pretty big. Wolfman Jack was arguably the most popular disk jockey in the United States, but not because he had the backing of a multimillion-dollar radio network or a magnificent agent. He was a radio outlaw and a mystery wrapped in an enigma. His shows were originally broadcast out of Mexican radio station XERF, which had a 250,000-watt transmitter that blanketed the entire United States. Nobody knew what he looked like. He did little promotion and made no TV appearances, but millions of people knew of him. All of that changed with the release of “American Graffiti.” This grand unveiling was the result of seeds planted by a fledgling disk jockey from New York City named Robert Weston Smith exactly 10 years earlier.

Big Smith with the Records

I’ve never been a fan of best-of lists. They’re so subjective and who is any publication with cursory knowledge to tell me who was the best was at something? But at the risk of contradicting myself, to me Wolfman Jack is the best American disk jockey of all time. There’s a lot of stiff competition out there; Dan Ingram and Cousin Brucie from WABC in New York, KHJ Los Angeles jocks the Real Don Steele, Humble Harve and Robert W. Morgan, Chicago jocks Dick Biondi and Larry Lujack and about a dozen others come to mind. All of them could certainly match the Wolfman’s energy for the music and his success, but I’d challenge that any of them equalled his passion. The Wolfman just felt the music and it came out in every syllable and reaction to what he was playing, and his own wits and mood dictated the songs he played on any given night, not a program director. But more than that, Wolfman Jack had a unique third facet that none of those others had, and it was deliberate and brilliantly constructed. It was the element of mystery. For the first 10 years of his on-air career, nobody knew who he was, what he looked like, where he broadcast from or what his nationality was. It’s the mystery that made him more compelling and bore a legend.

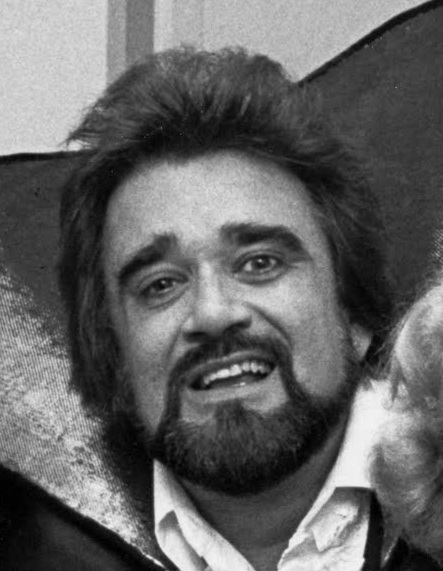

In real life, his name was Bob Smith, and he grew up in the Park Slope neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York in the 1940s and 50s. His family had endured a traumatizing set of extremes, living on the high end one year and then eking out a living the next. His father Anson Weston Smith, a stock market analyst, made and lost his share of fortunes before Bob came along. When he was born, family life was stabler financially with Anson serving as the executive vice president of “The Financial Times,” a bi-weekly investment magazine. Emotionally, however, it was another story with Bob’s parents divorcing when he was six. Anson and his wife Rosamund changed partners with another local couple and the only emotional stability Bob found was in his sister Joan, 10 years his senior. Soon enough she left to marry an Annapolis grad and was largely gone for Bob’s formative years.

By the time he entered his freshman year at Manual Training High School in Brooklyn, Bob lived with his father and stepmother in Prospect Park and began running with a teenage gang called the Tigers. They engaged in typical teenage delinquency, but usually hung out at Bob’s basement listening to the radio and immersing themselves in the sounds of black radio stations and jocks like Jocko Henderson on WDIA and Dr. Jive on WWRL. While it passed the time for the others, for Bob, it triggered his life’s calling and he got really dialed in when Alan Freed moved from WJW in Cleveland to WINS in New York, which quickly became the hottest radio program in the #1 market. It inspired Bob to set up his own makeshift DJ booth in the basement to entertain his buddies.

As Bob continued to skim up and down the dial taking in the sounds, the jock who inspired him the most was John Richbourg out of WLAC in Nashville who broadcast under the name John R. WLAC was a 50,000-watt clear-channel station, which means its signal permitted by the FCC to use that frequency and could reach over a hundred miles during daylights hours and even further at night. In many ways, John R. was the prefigurement of Wolfman Jack. He was a white guy who played R&B and doo wop records and affected his voice to sound black. He also talked up the record as it began playing and would often jump on the air during an instrumental break and provide commentary; two eventual Wolfman staples.

Bob’s affinity for black music was profound even then. He’d first been introduced to it by his parents’ live-in maid, Frances Gregory, a Southern transplant, who’d often rock him on her knee while listening to black gospel music on the radio. With blues and jazz bubbling underneath the surface of a national breakthrough, he naturally gravitated to the burgeoning post-war R&B deluge provided by artists like Bullmoose Jackson, Big Joe Turner, Louis Jordan and Johnny Otis. Their music was a joyous mixture of rhythm, raucousness and sexuality that went through several classification iterations like “race records” and “jump blues” before settling on the “rhythm and blues” moniker created by Billboard writer Jerry Wexler in 1949. With his deep love for R&B, the DJs who spun it and entertaining people coming together, Bob’s path was unfolding before him. Getting his parents on board for such an unorthodox living was a struggle. His father did his best to steer him toward a more traditional vocation, but the synergy of the music and his natural gift for gab was too strong and this forced compliance only made Bob lash out.

In high school, he secretly managed to get a job as a gofer at for Alan Freed’s Brooklyn Paramount, which averaged about four a year, but his father found out and put a stop to it. Not long afterward, he got nabbed stealing a car and his father enrolled him in the Friends Academy on Long Island for his sophomore year. He quit high school altogether midway through his junior year and his father enrolled him in a trade school to become an electrician, but that didn’t hold his interest either. By then, Bob lived with his father and stepmother at their new home in Short Hills, New Jersey and he’d skip class to hang out at the 5,000-watt black radio station WNJR in Union, New Jersey. Much in the same way he had at the Brooklyn Paramount, he got in by being a gofer and ended up being tutored on the mixing board by Russell Chambers who went by Mr. Jim.

Once again, dad found out, but this time, it was the final straw. He kicked him out of the house. It was more his stepmother’s idea. The two had no use for each other and poor Anson had no choice but to side with his wife. He gave him $300 to start his life and he and his friend Richie Caggiano boldly set out to make it in Hollywood but got no further than Bob’s sister’s house in Alexandria, Virginia. She lived in a nice suburban neighborhood with her husband Emile and their two children lived and the taste of domestic tranquility caused Bob to forget all about Hollywood. Emile was a kind, patient ex-Navy officer and the only family member to recognize Bob’s talent after watching him entertain his kids. He encouraged him to go to the National Broadcasting Academy in Washington D.C. The price tag was $3,000 and, with Emile’s prodding, Bob was able to get his father to foot the bill.

Among his classmates, Bob was a prodigy, and his focus was rhythm and blues radio. Shortly after graduation in 1959, he got his first job at WYOU, a black station in Newport News, Virginia. Under the tutelage of the Harvard-educated station manager, Joe “Tex” Gathings, he learned not only the live radio business, but, perhaps more importantly, the art of jive-talking. Ironically, the straightforward, traditional announcer, who happened to be black, refined Bob’s on-air banter to appear more genuine to their target demographic. WYOU’s studio was in the Hotel Warwick overlooking the James River and, before he knew it, Bob was knee deep in the seedy side of Newport News. In public, he was hosting a daily show, emceeing sock hops and auto shows, but behind the scenes, he was smuggling dope and pimping part-time, which dirtied his hands, but lent itself to the outlaw Wolfman image. He was also increasing his business acumen and developed such effective salesmanship that the tiny 1,000-watt station out by the docks of the Chesapeake Bay started turning a profit.

Success spelled his end there when station owner Robert Eaton sold WYOU to veteran D.C. broadcaster Max Reznick at the end of 1960. Reznick completely shed the station’s black image by changing the format to easy listening. He fired Tex Gathings and changed the call letters to WTID. Bob was retained but had to switch his hip on-air moniker of Daddy Jules to Roger Gordon. It took the fun out of work but did come with a promotion to music director. The only sensible thing Reznick did was hire Marvin Kosofsky as his sales director and station manager, but it sure didn’t seem that way at the time. When Bob first met him, he went under the pseudonym of Mo Burton and had no working knowledge of radio. In fact, he’d never been inside one, but he was a skilled bullshitter who answered Reznick’s want ad in “Broadcasting” magazine with such brazen confidence that he convinced the new owner to take a gamble. Mo was an NYU School of Law graduate but had more interest in hanging out in Greenwich Village cafes with his fellow beatniks than studying for the bar. Finally ready to get his life together and put his talent into action, he headed to WTID and quickly got to work. He and Bob became fast friends.

Mo did so well selling advertising that he convinced Reznick to make him a partner and shortly afterward purchased KCIJ, a small but failing 250-watt radio station in Shreveport, Louisiana. He took Bob along with him and made him its general manager, program director and morning show host where he took the on-air name, Big Smith with the Records. Before heading off for the Deep South, Bob married Lucy Lamb, a petite blend of backwoods North Carolina country girl, sophisticated dancer and budding Hampton Roads socialite who he lovingly called “Lou.” After exchanging nuptials, the two forewent the traditional honeymoon, loaded up their car and headed to KCIJ with Lou a couple of months pregnant. Little did she know that two bundles of joy were about to be born.

Here Comes the Wolfman!

On a mild winter day in late December 1963, Bob Smith and friend and KCIJ president Larry Brandon hopped into Bob’s Oldsmobile Starfire and cut a 600-mile diagonal swath across the state of Texas to the border town of Del Rio. Their aim was to cross into Mexico and get on the XERF airwaves and introduce an R&B force of nature to the entire United States. At 250,000 watts, XERF was the most power station in the world and blasted its signal clear across the United States and into parts of Canada and Europe and could be heard as far away as Australia. Its signal emanated from a desert tower outside of Ciudad Acuna where unbridled wattage was permitted because of fewer stations and a sparser Mexican population. Since he was a kid in his parents’ basement, Bob had been obsessed with XERF, especially the gospel preachers with supreme evangelical rapport like Brother A.A. Allen and Rev. Ike who dominated its daytime airwaves as well as Big Rockin’ Daddy who played R&B at night. Because of its long reach, he’d always dreamed of broadcasting from there and figured his best course of action was a cold call. He was in a professional rut and there was something special deep inside of him clawing its way out.

They say that necessity is the mother of invention and that was certainly the case in Bob Smith’s development of his Wolfman Jack character. It’s something he’d been kicking around in his head for quite some time, but he had no idea how to implement it until he started playing country music full time at KCIJ. He had nothing against the music, but it didn’t satisfy him spiritually like R&B did, and he needed an outlet for this alter ego.

Wolfman Jack came from a myriad of Bob’s personal and professional life experiences. He was able to play act some with his Daddy Jules character back on WYOU and it served as a blueprint, but he desired something greater that would provide an outlet for his unbridled energy and passion for the music. Part of it came from his love of horror movies. Coming of age in the 1950s, movie theaters were rife with B-movie horror and sci-fi movies like “The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms,” “Godzilla” and “The Creature from the Black Lagoon.” And back in those days, the three networks would often play old black and white movies like Frankenstein, Dracula and the Wolfman series on the late show. Bob was especially inspired by the latter whenever he used to play with his nephews by pretending that he was the famous Lon Chaney Jr. character and saying to them in an affected, gravelly voice, “The Wooolfman man is coming down the hall…he’s coming to GET YOU and EAT YOU UP!” It was the first time that voice emerged, and he reached back to it while developing this new character. With R&B records, it was a great combination because it made him sound like a blues musician. He added the surname “Jack,” which was common in post-war slang. “Hit the Road, Jack,” “Ballin’ the Jack.”

Bob believed XERF was the perfect platform for this new character, and it was do or die. When he and Larry showed up at the station in mid-December, they walked into the middle of a labor dispute between a Mexican intervenor and 13 recently fired employees. The station was so powerful and had so much reach, that it became a cash cow for whoever controlled it. It was one of a series of border blasters made popular in the 1930s and 40s by quack doctor John R. Brinkley’s 50,000-watt XER station who used it to sell his goat gland treatments that promised to prolong and enhance the male sexual experience. Over the next two decades, these border blasters were exploited by radio evangelists who most often would buy 15-minute time slots to hock everything from Bibles to prayer packages and healing water and it wasn’t hard to separate listeners from their money and rake in millions.

XERF was founded by Mexican attorney Arturo Gonzales and a few silent partners on the old XER site in 1947. The tower was boosted to 100,000 watts and then upgraded to 250,000 watts in 1959. By December 1963, the station owed some serious back taxes, and the deficit was deliberate. Around 1961, Gonzales devised a long-term scam on the preachers who broadcast on his airwaves and paid tens of thousands of dollars annually in time slots and advertising. Gonzales would gradually increase the rates much to their consternation, but their profits were too great, so they always capitulated. As a compromise, he proposed a one-time $1 million lifetime guaranteed payment, so they’d never have to face another rate increase. It seemed like a good deal, and each returned the contract Gonzales mailed to them with their signature. There was only one tiny, overlooked little clause which nullified the deal if the government ever took control of the station.

The tax evasion guaranteed that eventuality and the clause never laid out the specifics of a government takeover, which primed the pump for the scam. The Mexican government indeed took notice when XERF’S debt hit around 500,000 pesos, along with 300,000 in employee back wages. An intervenor, Ciudad Acuna attorney Saul M. Montes, was appointed to run the station until the back taxes, wages and interest were paid in full. What Mexico City didn’t know is that he was in league with Gonzales. He could run the station, skim from the ad profits and, once it was out of arrears, hand it back to Gonzales who could then rewrite all contracts for his wealthy stable of radio preachers. It was devious, corrupt, and underhanded and got downright banana republic when Montes appointed Gonzales as his U.S. sales representative. He delivered the bad news to folks like Brother Allen and Rev. Charles Jessup that their previous contracts had been voided by the government and the rates were now doubled, which went over like a fart in church. They had no choice but to pay up while simultaneously sending their lawyers after XERF to no avail.

Montes had promised that all back wages would be paid within a week of him taking over in May 1963, but it didn’t happen. The fired employees, who all wanted their jobs back, were still waiting by the time Bob and Larry arrived that December day. They suspected, and were probably right, that Montes was dragging his feet and lining his pockets to the tune of about $150,000 a month in ad profits. If he was ever going to get Wolfman Jack on the air, Bob’s best bet was to side with the ex-employees. Through the assistance of one guy who spoke English, he was able to rally the unionized group and hatched a plan to ice out Montes by naming him as their U.S. representative. He and Larry came with a bundle of cash and slipped each cohort a C-note and traveled with a small faction of attorneys and employees to Mexico City to plead their case and get formal control of XERF. The entire endeavor was financed by a $15,000 counter check taken out of a KCIJ account without any approval from Mo. Not only did they face the tall task of taking over the station, but they also had to get the money back before he found out. It was the gamble of a lifetime.

In the meantime, Bob and Larry decided to go ahead and take the station over anyway and turned it into Fort Apache by fortifying it with guns and barbed wire. Their next step was to notify all the radio preachers, who they knew through advertising on KCIJ, that XERF was under new management, and they’d need to pony four months advance payments to keep their spots and pre-taped shows in their dedicated timeslots. They all balked. That gave Bob the green light to debut Wolfman Jack, which would satisfy him professionally and simultaneously send a serious message to them.

On a cool night in late-December 1963 at 7:00 pm CST, the maniacal sounds of Bob Smith’s inner animal came howling out across North America, Central American, the Caribbean Islands and beyond on 250,000 watts of radio power. He preempted Rev. J. Charles Jessup, Dr. C.W. Burpo’s “Message to Save America” and blasted right through Mary Trinqual’s “Fountain of Life” and Brother A.A. Allen’s “Revival Hour” and played rhythm and blues into the wee hours of the morning, interspersed with Wolfman Jack’s raps, howls, “Can you dig it’s” and “Have mercy baby’s.” Once all the radio evangelists realized their biggest moneymaker was indeed threatened, they paid up quickly.

The following day, Bob and Larry set up shop outside the Del Rio Western Union office collecting wire transfers from radio evangelists across the U.S. that amounted to $350,000. They were able to repay the money they commandeered from KCIJ, which didn’t stop Mo from firing both of them, and pay all the ex-employees’ back wages, which made him “Salvadora de la estacion.” Things looked golden, but he still had Montes to deal with, and the threat of retaliation forced Bob to travel to and from XERF with armed bodyguards. They did, after all, hijack his station. A few weeks later, on January 20th, he struck with an armed squad loaded with 30-calilber rifles and submachine guns on trucks and horseback. Bob was in his Del Rio Hotel room getting reacquainted with his visiting wife with XERF playing softly in the background. Suddenly, he heard one of the engineers interrupt a pre-taped religious show with screams of, “Pistoleros! Ayudanos! Pistoleros!” Bob didn’t speak Spanish, but he knew what pistoleros meant. He jumped out of bed and, as quickly as he could, assembled a cavalry who beat feet to the station where an Old West-type gun fight ensued. It didn’t take long for Montes’ men to retreat when the Acuna police and a small Mexican garrison followed behind Bob and his squad, but it did leave Gilberto Alvarado, one of Montes’ men, dead from a gunshot wound to the back of his head. Nobody was charged and when Montes retreated, business at XERF resumed as usual.

A few days later, Montes attempted to assassinate Bob in his hotel room, but got thwarted when the clerk tipped him off. Bob hid under his bed and returned fire. Things settled down and Wolfman Jack exploded into American pop culture. For the next nine months, he aired live daily, and Bob began hawking his own products and making money hand over fist. But he’d made too many enemies and couldn’t keep his young and growing family around this type of heat. They headed back north permanently at the end of 1964 and to Mo Kosofsky who’d forgiven him for stealing his money.

The Soul Monster

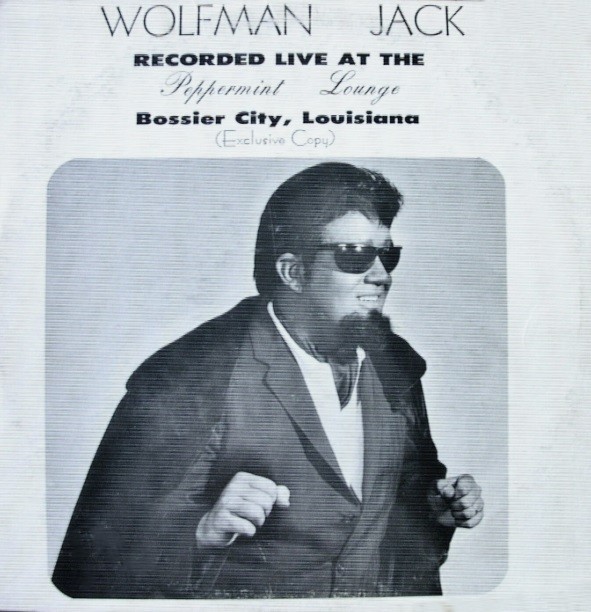

As Wolfman Jack started gaining in popularity, Bob began making public appearances in character at the Peppermint Lounge in Bossier City, the sister city to Shreveport. He even preserved his bizarre live shows there on wax with local group the Rhythm Kings and sold it locally. The etymology of the Wolfman’s look was fascinating, and home grown. Bob wanted to keep the Wolfman enigmatic and deliberately changed up his appearance, but he often looked like he belonged in an Ed Wood movie with dark makeup to hide his ethnicity and cheap store-bought wigs and a stick-on beard.

But it wasn’t long before Bob hit another professional snag. Bossier City was Louisiana’s attempt at Las Vegas with gambling, prostitution and much looser alcohol and segregation laws. Following a Wolfman Jack performance in August 1964, some local Ku Klux Klan members got into a cross-burning frenzy. They set up shop one night outside the Peppermint Lounge and set it ablaze when he and his party exited and followed that up with another one on his front lawn when he arrived home. It scared Bob enough to pause live performances for a while.

He got an exit ramp out of the Deep South when Mo offered him the executive vice-president and general manager position at his latest station, KUXL, a 1,000-watt R&B station in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Like so many mid-major market stations, it was a hodgepodge of programming that catered to its demographic and Bob jumped on it without hesitation. He could go back to playing R&B, but, more importantly, was the man in charge and free to pre-record his Wolfman Jack shows and ship them to XERF. By then, all shows beaming into the U.S. from Mexico by law had to be pre-taped. There had always been acrimony between the FCC and border blasters, so, in the interest of fairness, this deal was worked out. Bob had no issue with this because, like Lon Chaney Jr.’s character in the 1941 film of the same name, the Wolfman was itching to get out full time and be nationwide.

Despite this new opportunity, Bob was ready to make Wolfman Jack his permanent thing and he got in touch with Harold Schwartz, a Chicago-based radio magnate. Along with his Mexican partner Teo Bacera, he either owned or had a controlling interest in many of the border blaster stations, including XEG in Monterrey and XERB in Tijuana. Schwartz was also the U.S. representative and top ad man for XERF and XELO in Juarez and was responsible for first getting evangelists on those stations. He was very familiar with Bob’s Wolfman Jack persona and was eager to do business with him. After a fruitful meeting in his Chicago office, Bob was given full control of programming at 1090 XERB, a 50,000-watt station with its tower located south of Tijuana in Rosarito Beach, Baja California. For years, it featured country and western and gospel programming and was run by country singer/songwriter Smokey Rogers. Los Angeles was right in its crosshairs and Bob goal was to make it the top R&B station in the market. He established its U.S. office and studio right on the Sunset Strip and brought with him KUXL jocks Art Hoehn who went by “Fat Daddy Washington” and Ralph Hull who used the pseudonyms “The Nazz” and “Preacher Paul.” In February 1966, three white DJs from Minnesota quietly set out to take L.A. radio by storm and, for about six months, went about designing tempo-based programming and personally met with their target audience to see what they were listening to and gauging the station’s reach with a tiny transistor radio in hand.

When Bob began “The Wolfman Jack Show” on XERB in August 1966, he was still fleshing out the character. He still had the gravelly, growling voice still going, but it was raw and unrefined and possessed a Southern drawl. Over time, that would evaporate as live reads became more prominent and he had to communicate effectively for his advertisers. The setup for their shows was so cloak and dagger that it almost seemed illegal. They would send several reels of tape along with instructions by Greyhound bus to Tijuana every day to skirt any possible customs regulations, and regular border guards got their palms greased to prevent any red tape from holding up delivery. For the Wolfman Jack Show, Bob would record song intros and outros in real time a day in advance and put them on one reel. To give his shows a live feel, he’d take phone calls from listeners and include several throughout each one. It was a bit of manufactured image, but it worked to great effect. Each night, he’d invite his audience to call their studio line and when they did, they’d get his answering machine with a greeting that encouraged callers to leave their dedications and callback numbers. He’d call the best ones back and record the entire exchange on his Ampex reel- to-reel recorder. The selected phone calls were duped onto a separate reel and shipped along with his aircheck to Tijuana. A then-19-year-old Lonnie Napier began working for the Wolfman in 1970 and duping those calls was his first job of many.

“He wanted me over the next six months to go through this stack of 12-inch tapes that probably went up to the middle of my body,” he told me recently. “And there were thousands and thousands of requests and stuff from people.”

An absolute requirement of competing with the bigger L.A. stations was having great jingles and XERB had some of the best. It was a great mix of professional imaging, most likely the Johnny Mann Singers or PAMS, with Ralph and Art handling most of the station IDs in the beginning. In 1968, legendary L.A. jock the Magnificent Montague became the voice of the station. His booming baritone and new jingles supplied by one of the many black gospel groups brought in by XERB religious host Brother Duke Henderson brought an urban grittiness to XERB that appealed to Wolfman Jack’s target audience and can be heard throughout “American Graffiti.” To cap it all off, Wolfman Jack dubbed his new station “the Mighty Ten-Ninety, 50,000 watts over Los Angeles,” “the Big X” and “the Soul Monster,” replete with all the gospel preachers, crazy products, record albums packages and “cash, check or money order!”

Southern California Giant!

At 50,000 watts, XERB was the weakest of all the border blasters, but it made up for it by covering the second-largest radio market in America. Bob wanted to go beyond that. To maximize exposure, he and the folks down in Rosarito Beach installed directional reflectors on the radio tower to give the beam a lobed shape that would hit dry land instead of the Pacific Ocean. The redirection essentially gave XERB the reach of a 150,000-watt tower, blasting into 13 states, stretching as far north as Anchorage, Alaska and as far East as Denver, which gave it an audience of about 3 million.

Over his six years running XERB, Bob had lots of show turnover. His early morning and midday programming were the old radio preachers from XERF, that got paired down to mornings with Brother Henderson’s “Glory Bound Train” program and two hours before Wolfman Jack’s night show starting at 9:00 pm. Ralph and Art were fired near the end of 1967 and by 1969, the two main jocks were the Wolfman and the Magnificent Montague. Subsequent hosts included Dick “Huggy Boy” Hugg, Art Laboe, E. Rodney Jones, Johnny Otis and Robert W. Morgan, and Bob would also bring in top R&B musicians like James Brown, Joe Tex and Eddie Harris to record airchecks for their own XERB shows.

But none of them could unseat Wolfman Jack as the most energetic, exciting and compelling disk jockey on the station. In the August 28, 1966 edition of the Los Angeles Times, staff writer Don Page wrote, “Wolf Man makes KHJ and KFWB sound like rest homes.” Tom Saxe of the Daily Times-Advocate in Escondido, California called him “the hottest thing to happen to radio since the vacuum tube.” Long time West Coast radio host and executive Michael Hagerty first heard Wolfman Jack on XERB when he was 11 in early 1967.

“I didn’t know a lot of what he was talking about, but there were absolutely drug and sex references that were nowhere else on the AM dial,” he told me. “That ‘should I be listening to this’ feeling lasted maybe a year or two.”

In the first couple of years, his playlist mirrored much of what was hitting the Billboard and Cash Box R&B charts that came from top labels like Motown, Stax and Atlantic. But to differentiate themselves from the top black L.A. station KGFJ, they freely mixed in deep toe-tappers that caught Bob’s ear like “She’s Lookin’ Good” by Rodger Collins and “You’ve Got the Makings of a Lover” by the Festivals along with his three longtime favorites, Ray Charles, James Brown and Aretha Franklin. Also present was a steady mix of T-Bone Walker, B.B. King, Muddy Waters and other traditional blues artists, and his love for the jazz organ showed in contributions by Brother Jack McDuff and Jimmy McGriff. In time, his show incorporated more mainstream rock and pop like Creedence Clearwater Revival, Three Dog Night and even Bobby Sherman and Edison Lighthouse.

“While we are basically a black station, the 18-25 age we are trying to reach buys the Beatles, Creedence Clearwater Revival, the Rolling Stones and all the heavy rock bands,” Bob told Billboard Magazine in 1969.

XERB was a hit for the six years Wolfman Jack was on its airwaves and was often the top R&B station in L.A., but he could never beat out the top dogs KHJ, KFWB and KRLA. His main competition at night, KHJ’s Humble Harve, was pulling in a 14-share to Wolfman’s one. But Bob was never in it to unseat them. He wanted XERB to sound like it come from outer space and made full use of the border blaster’s advantages. It also made him a wealthy man. At its peak, Bob was raking in $50,000 a week and was living in the Hollywood Hills, a claim even the top L.A. jocks couldn’t boast.

Clap for the Wolfman

By the end of the decade, the Wolfman Jack Show included a steady mix of 1950s R&B and rock and roll records in his daily shows, and he talked them up like he was hearing them for the first time. And you could always tell he was really enjoying a song when he’d drop a wolf howl or “Right on, Wolfman, right on” in the middle of it. It’s most likely because of this that George Lucas and screenwriters Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck purposely included Wolfman Jack as the mysterious DJ whose show ties together his four main characters in “American Graffiti,” which takes place in August 1962. They were all twentysomethings when the Wolfman came out of nowhere and flogged the nighttime California airwaves. Huyck and Katz personally visited the Wolfman at his new KDAY gig to pitch him on being in the movie.

“The station happened to be three blocks from where we were living, so we drove to visit Wolfman,” Huyck said in the 1998 documentary, “The Making of ‘American Graffiti.’” “It was like meeting an icon…we had grown up with Wolfman Jack.”

While they may have first caught Wolfman Jack on XERF, it’s from his days at XERB that they fell under his spell and it’s that persona which appears in “American Graffiti.” The Wolfman Jack Show provides the movie’s entire soundtrack and is the common bond between virtually every character as he plays on car radios while the characters cruise the circuit on a crazy summer night of misadventure, oat-sowing and hijinks. Not only does he spin a great playlist of early rock and roll and pre-1962 R&B and doo wop, but typical show elements like crazy phone callers, messing with telephone operators and elements that only dedicated listeners would understand like saying “Wiss, wiss” repeatedly with reverb, reciting love sonnets and asking callers if they’re “Floyd” are included. Regardless, his show in the movie is enjoyable and enticing. The film even takes advantage of the mystique that surrounded the jock during his border blaster days.

Black or White?

“I just love listening to Wolfman. My mom won’t let me at home…because he’s a Negro,” says the character of Carol played by 13-year-old McKenzie Phillips to the film’s tritagonist John Milner played by Paul LeMat.

The ethnicity of the Wolfman Jack was a secret and a well-guarded one for much of his time at XERB. His gravelly, soulful voice sounded more black than white and XERB was directed at the black demographic. In 1968, a reader named Robert Banducci wrote into the Richmond, California newspaper “The Independent” and asked the editor if Wolfman Jack is “Negro or Caucasian.” The editor most assuredly responded that Wolfman Jack is indeed “a Negro” and that he “broadcasts in a falsetto.” Beginning around September 1967, Bob began making public appearances again and constructed another revue with live music and him doing Red Foxx-style dirty comedy. Newspaper advertisements for them would often include a pencil drawing of Wolfman Jack, which didn’t do much to remove the veil and he got several years of traction out of this mystery.

Location, Location, Location

In that same “American Graffiti” sequence, the film cuts to protagonist Curt Henderson, played by Richard Dreyfuss, who’s been abducted by a gang called the Pharaohs and rides with them in their custom 1951 Mercury lowrider. One of the members, Carlos, played by Manuel Padilla Jr., reacts boisterously to Wolfman Jack messing with a telephone operator who placed a collect call.

“You know he broadcasts out of Mexico someplace,” he tells gang leader, Joe, played by Bo Hopkins.

“No he don’t,” Joe responds. “I seen the station right outside town.”

“That’s just a clearing station, man…so he can fool the cops,” Carlos retorts. “He blasts that thing around the world. It’s against the law, man.”

The mystery of where the show emanated from was a real thing for its first couple of years. The confusion was understandable and partly manufactured. The Wolfman Jack Show had been around on a regular basis on XERF since January 1964, but many of the pre-recorded show also aired on 100,000-watt XEG out of Monterrey, Mexico. By the late-1960s, his XERB shows were syndicated on XEG and XERF and was beginning to get picked up by U.S. markets. Its emanation point, however, remained a mystery that many a journalist tried to figure out. In the January 28, 1967 edition of Billboard, writer Eliot Tiegel called it the “mystery” station and did his best to unravel its ownership, and he came pretty close linking it to a “corporation in Chicago, which in turn reports to a Mexican company.” The Tyler Courier-Times out of Tyler, Texas did a better job of getting to the bottom of things less than six months later when writer Pete Johnson stated, “Most of his show is done on tape…XERB transmits out of Tijuana, Mexico, although its business offices are in Hollywood.”

Are you the Wolfman?

The final and biggest mystery Lucas addressed in “American Graffiti” was the Wolfman’s identity and it was a closely guarded secret for most of Bob’s XERB tenure. In the scene where Curt Henderson goes to the studio that Joe the Pharaoh referenced earlier in the film, he encounters the mysterious disk jockey who shows, to Curt’s disbelief, that Wolfman Jack is on tape.

“Where is he now? Where does he work?” Curt asks.

“The Wolfman is everywhere,” the mysterious disk jockey responds.

It was a G-rated version of real occurrences. Back in his XERF days, whenever a reporter would call the studio or bravely trek across the Chihuahuan Desert in hopes of encountering the Wolfman in person, they’d be greeted by Bob Smith who’d tell them the Wolfman lives in Mexico City where he stars in porno movies. After their conversation, Curt begins to exit the dark station as “A Thousand Miles Away” by the Heartbeats plays over the air. In a Wizard of Oz moment, he hears Wolfman Jack come in and talk over the record. Through a small studio window, he sees that the man he’d been talking to was in fact Wolfman Jack. Curt’s reaction is deliberately obscured by darkness, leaving it up to the viewer to determine his reaction.

Many L.A. entertainment writers openly questioned the Wolfman Jack’s identity like he was Superman, and there were more than a few that referenced program director Bob Smith and Wolfman Jack as two separate individuals. By the end of 1969, Billboard Magazine writer Eliot Tiegel finally got to the bottom of the mystery. In a lengthy article highlighting the inclusion of rock artists into XERB’s playlists, he revealed Bob Smith as Wolfman Jack and shares how the shows are constructed and from where they emanate. But, being mostly a trade journal, few listeners and fans read it. “American Graffiti” was in essence the Wolfman’s coming-out party.

On April 15, 1972, the final Wolfman Jack Show aired on XERB, which was now known as XEPRS or XPRS. Once again, corruption overtook common sense as the new Mexican ownership teamed with its government to outlaw evangelical programming so they could get a bigger cut of the pie. It did the opposite by wiping out the lion’s share of the station’s income and forcing the exit of Wolfman Jack. Under the direction of new agent Don Kelley, he bolted for KDAY, ironically the same station Alan Freed fled to following his ouster from New York over the payola scandal. Ads featuring a real picture of the Wolfman Jack started springing up in L.A. newspapers and a large billboard with his face on it overlooked the heart of the Sunset Strip.

Following the success of “American Graffiti,” WNBC radio in New York offered him a high paying evening show and he got the gig as the host of NBC television’s late-night “Midnight Special” weekly concert program. The Guess Who hit the Top 10 in 1974 with “Clap for the Wolfman,” featuring voiceovers by the DJ himself and Wolfman Jack became a national treasure. His later career was that of a high-paid radio journeyman on all types of stations and we lost him too soon from a heart attack at the age of 57 on July 1, 1995. The Wolfman still is, in fact, everywhere as his “Graffiti Gold” shows still appear in syndication on many U.S. radio stations. Please join me in cheering on the greatest DJ who ever lived and do it now while it’s fresh on your mind.

So the whole Wolfman Jack strand in ‘American Graffiti’ is a historical anachronism

Oh well! Still captures the musical spirit of the time