By Scott Shea

In the dead of Winter 1973, Greenwich Village in lower Manhattan was still a live music hub but was a far cry from being the Mecca of folk music that Bob Dylan and many other young musicians walked into over a decade earlier. By the late 1960s, folk music’s arch nemesis rock and roll had been fully embraced there by club goers and owners and many began hosting a new breed of rock and roll artist like Lou Reed & the Velvet Underground, David Bowie, Iggy Pop & the Stooges and Alice Cooper. And much like folk did in the early 1960s, this acceptance would foster homegrown talent and make it the homebase of the glam rock scene with local artists the New York Dolls, the Magic Tramps and Dorian Zero, setting the scene for punk rock which lay on the distant horizon.

But on January 17, 1973, Max’s Kansas City, one of the Village’s preeminent clubs, located diagonally across the street from Union Square, hosted an artist that not even those musical pariahs could wrap their countercultural minds around as he walked to center stage in sod kickers, jeans and a cowboy hat. What is this, country music in the Village? Even their parents didn’t listen to that. Nobody north of Philadephia did, right? When this enigma took the stage with his small band, some surly New Yorker in the relatively small crowd shouted, “Who the hell are you?”

“I’m Waylon ‘Goddamn’ Jennings,” he replied boldly. “And this is country music.”

He was booked for six nights and stood on the edge of not only a major musical shift but leading a cultural one as well. Playing Max’s Kansas City certainly wasn’t Waylon’s idea, but his willingness to go along reflected his tendency to not go by the book and bring his music to the margins. To his peers and the Nashville system, it made him an outlaw.

Nobody can accurately say when the Outlaw Country Music Movement started. It’s like the ridiculous question, “What was the first ever rock and roll song?” But one thing that’s certain is Waylon Jennings was its primary catalyst and the face of it along with Willie Nelson. But, back in January 1973, hardly anybody outside of Nashville had heard of him and even Music City didn’t really know much about him. Waylon came to Nashville eight years earlier as an outsider from Phoenix, Arizona where he was the king of the nightclub scene. Since summer 1964, he’d been the feature act at JD’s, a mammoth two-story nightclub built on the outskirts of the campus of Arizona State University that brought in a mix of locals, university students, minor league baseball players and desert cowboys. His setlist was just as eclectic. It was mostly country, but also featured a mix of rock and roll, folk and R&B, all with a country undercurrent that was more Bakersfield than Nashville. And, by and large, that’s what the Outlaw Country Music was all about.

Folk-Country

Back when 18-year-old Waylon was a fresh-faced DJ in his hometown of Littlefield, Texas, Nashville producers were crafting a response to rock and roll, which hit the mainstream with full force in 1956 and threatened its very existence. The line between the two music forms became blurry. The answer has since become known as the Nashville Sound, but, in retrospect, the formula was simple; update the sound with modern studios and arrangements while maintaining a country music fingerprint and that meant investing. For years, most major artist recordings were done in a converted banquet room at the Hotel Tulane in downtown Nashville or at Jim Beck’s Studio in Dallas, Texas. But by the mid-1950s, their sound was primitive in comparison to records being cranked out in New York and Los Angeles. Even studios that catered to rock and roll artists, like Sun in Memphis, Tennessee, began utilizing a slap back echo effect, which gave them a much more modern sound.

The good thing for the country music cognoscenti was that, at that point in time, Nashville was mostly an empty canvas that allowed for new studios with state-of-the-art equipment on par with what was being cranked out in rival cities. The first was financed by Decca country music chief Owen Bradley and his younger brother Harold who imported a World War II Quonset hut to the backyard of a house they purchased on 16th Avenue and loaded it with modern recording equipment. And drums! For decades, the basic rhythm instrument was considered anathema in country music mostly because of its ties to evangelical churches, which considered the measure an occasion of sin. Now they were essential if it was going to keep pace. Bradley Studio B, as it was officially named, quickly become the premier destination for country artists on most major record labels. Not to be outdone, RCA Victor built a rival studio just up the street and others quickly followed, renaming the neighborhood Music Row and creating a cottage industry two and half miles southwest of the Grand Ole Opry.

Producers like Owen Bradley, Chet Atkins, Bob Ferguson, Don Law and others now began fashioning records that matched the crispness of their pop counterparts, but often included twin fiddles, pleasant background singers and the relatively new pedal steel guitar, which never sounded better with balanced reverb mixed down on four and eight track mixers. Everybody benefitted, from established artists like Ernest Tubb, Eddy Arnold and Kitty Wells to newbies like Ray Price, Johnny Cash and George Jones.

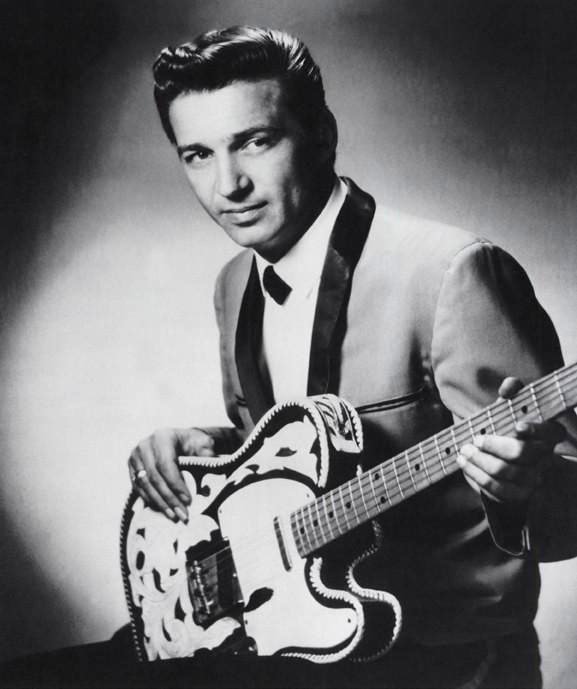

But by the time Waylon arrived in 1965, the Nashville Sound was beginning to collapse under its own weight. Country music was the most conservative of musical communities and resistant to change. While great records were still being made, experimentation was discouraged, outsiders were considered suspect and the strings and background singers that once gave charm to many records were now beginning to overshadow the artists and blurring the lines between adult contemporary and country. Newcomers like Waylon and Willie Nelson weren’t afforded the type of flexibility that had been allowed a mere 10 years earlier. Nevertheless, Chet Atkins immediately sought to accommodate Waylon’s unique sound, which had a much more thumping rhythm section, a guitar more akin to Buck Owens and Don Rich than anyone in Nashville and a complete lack of fiddles and steel guitar. The records were quality and pleasantly different from the get-go, but unfortunately undermined by the “Folk Country” stamp placed on the record cover.

It was an idea conceived by Chet Atkins that seemed to serve a dual purpose. For label executives, it acted as a sort of warning label to let consumers know that these artists were experimental, and that the winning formula wasn’t being messed with. Hard core country music lovers didn’t have to waste their money checking them out. For new customers, who were possibly venturing into country music for the first time following the folk boom of the past few years, they could rest assured that these records didn’t contain all the traditional country music accoutrements and someone singing through his or her nose. Unfortunately for the Waylon, the former outweighed the latter.

In the conservative South, folk music was viewed with a wary eye because it was often performed by northerners who had direct ties or sympathies for communist countries and organizations and their songs for the worker were often a form of communistic proselytizing. They weren’t entirely wrong either, but this unforced error lumped singers like Waylon Jennings, Bobby Bare and George Hamilton IV in with black-listed folk singers like Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie and Josh White. And even though Seeger’s young protégé Bob Dylan had abandoned folk music for rock and roll by 1965, that news hadn’t quite reached rural southerners and it didn’t help that many of his songs graced many of RCA Victor’s “Folk Country” artists’ records. Waylon’s 1965 RCA debut LP didn’t contain any Dylan songs, but it was called “Folk-Country” and his portrait on the cover made him look more like an Ivy League political science professor than a country singer. These mistakes by his label may have done Waylon a disservice in the short term, in the bigger picture, it kickstarted his Outlaw persona particularly as national sympathy for the Vietnam War began to wane.

Highwaymen

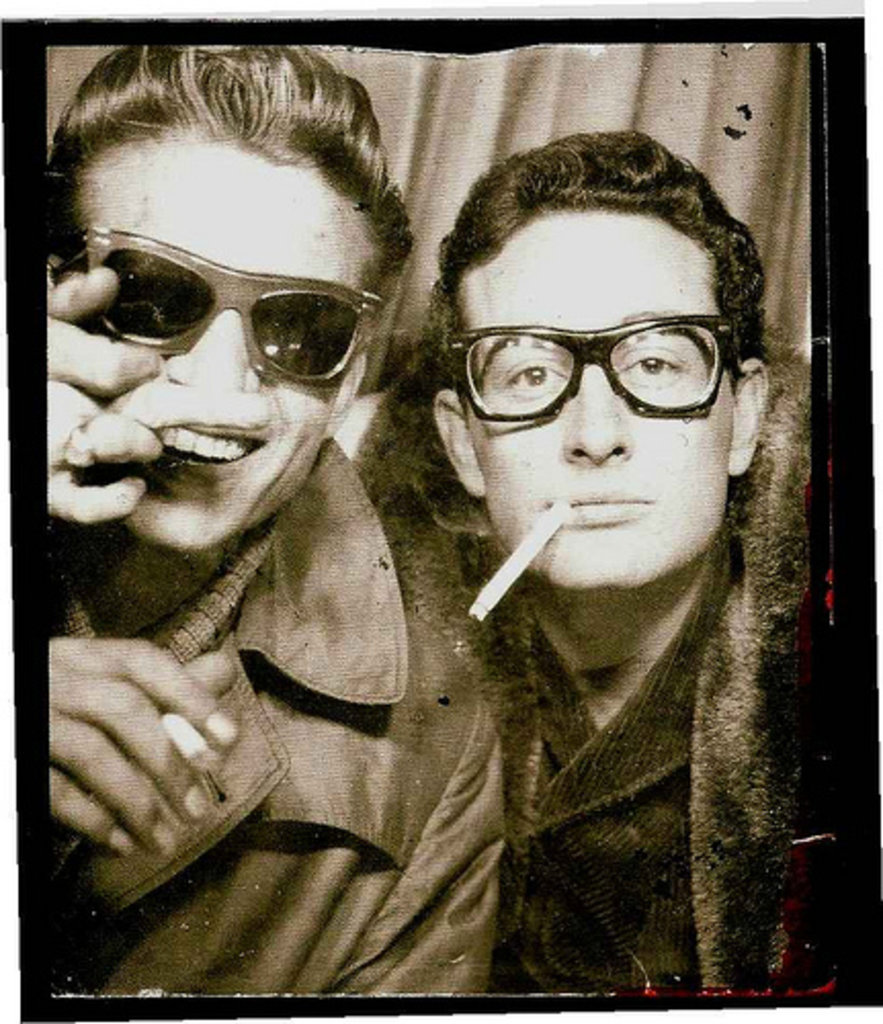

Waylon Jennings’ musical journey was shaped in part by the people he met along the way and many notable ones shaped his style. It began in 1958 with Buddy Holly who took such a liking to him when he was hosting the midday show at KLLL in Lubbock, Texas that he took him on as his bassist for his ill-fated Winter Dance Party Tour in January 1959. A pre- “Folk Country” Bobby Bare caught wind of him while passing through Phoenix in 1964 and introduced himself after one of his nightly performances at JD’s. It eventually led to his signing with RCA Victor the following year. Before his first gig at JD’s, he hired a young drummer from Bagdad, Arizona named Richie Albright who he’d first met a year earlier. JD’s was high paying and was designed for dancing. Waylon’s early Johnny Cash style affinity for a drum-less rhythm section would have to give way, and Richie would go on to become one of his closest friends and confidants, not to mention a chief architect of his Outlaw sound.

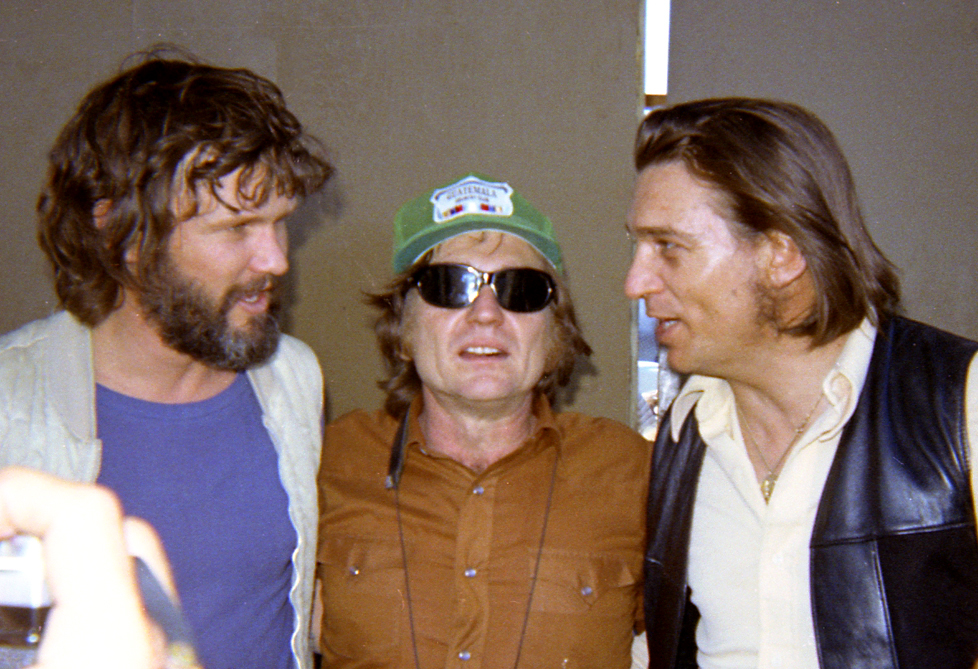

But there were three other musicians he met during his early RCA days that forged his sound and personality and would remain with him for the remainder of his career. In the 1980s, they’d even band together to form a super group eventually called the Highwaymen. The first was Johnny Cash who Waylon first heard while working as a farm hand around the time he’d had his first hit on Sun Records. By the time he and Waylon crossed paths, when Johnny and his future wife June Carter were playing in Phoenix in 1964, the Man in Black was a full-blown amphetamine addict, which made them a perfect match because Waylon was too. He’d first encountered them while touring with Buddy Holly and reintroduced through guitarist Shirl Milete on a disorganized, haphazard tour of the Rocky Mountain states in 1961.

For Johnny, pills had tarnished his reputation and, along with his affinity for the folk movement and singing Bob Dylan songs, had made him an industry outcast in the vein of Hank Williams. He seemed to be on the trajectory for a similar fate too. Busting out the footlights recently on the Grand Ole Opry stage with his microphone stand in a pill-filled rage didn’t help ingratiate him to the Nashville elite either, but it helped make him the original Outlaw. When Waylon moved to Nashville in 1966 to be closer to RCA Victor’s studios, he and Johnny rented an apartment together at the Fontainebleau Apartments in Madison, Tennessee. It was a lark for Johnny. He certainly could afford a big house in a wealthy neighborhood, but he was freshly divorced and constantly high and opted to stay with Waylon simply for the fun of it. The two mused about their time as roommates on the March 25, 1970 episode of the Johnny Cash Show on ABC where Waylon told a favorite story about Johnny trying to make biscuits and gravy while wearing one of his trademark black suits.

“Can you imagine Johnny Cash in a black suit with baking powder all the way down and gravy on the hair?” he asked the amused audience.

In Johnny, Waylon found a kindred spirit in addiction, although they hid it from one another, and a friend of lofty stature. He was something to aspire to and showed that you can be imperfect and still make it to the top of your game.

A few months before leaving permanently for Nashville, Waylon met fellow Texan Willie Nelson for the first time while he was in town performing at the Riverside Ballroom in downtown Phoenix. Waylon was so big there that Willie couldn’t help but notice the JD’s signage and advertisements everywhere as well as hear his name being bandied about considerably in the hallways of RCA Victor Studios back in Nashville thanks to Bobby Bare and Skeeter Davis. Like Waylon, Willie had started off as a DJ and used it to work his way into the music industry, although his unorthodox singing style was working against him for many years. He turned to the pen and began writing songs to pitch to other artists. He’d been writing since he was seven and had become somewhat of a country poet. After moving to Nashville in 1960, he’d hit a smash trifecta with the songs “Hello Walls,” “Funny How Time Slips Away” and “Crazy.” Each had become big hits for Faron Young, Billy Walker and Patsy Cline, respectively, and put his name in the collective conscience of the country music elite. By 1962, his songs were in high demand, and he’d been rewarded with a recording contract from Los Angeles-based Liberty Records. Though he had a couple of early hits, he’d hit a wall by 1964 and, after a cup of coffee with Monument Records, landed on RCA Victor under the direction of the legendary Chet Atkins.

He was less than a year in and still searching for his first C&W hit when his and Waylon’s paths crossed. Waylon was making a mint playing JD’s but wrestling with the decision of either staying and commuting to Nashville for recording purposes or moving there to be closer to the action. He sought his new labelmate’s advice.

“Don’t move,” Willie told him. “And if you do, let me have that job.”

Waylon ignored his new friend’s advice and headed to Nashville after the New Year. It set the stage for their complicated and often comical friendship, which, from the outside, resembled Ralph Cramden and Ed Norton or Bud Abbott and Lou Costello with Waylon serving as the straight man. And like those friendships, it eventually became incredibly profitable. Waylon and Willie weren’t chums during their early Nashville period, but gradually grew closer together as the 1960s dragged on and their frustrations with their label grew. In the ensuing decade, as their tastes expanded, each would often serve as a sounding board for the other.

The third influential figure was another new Nashville resident who’d also once called Texas home. Kris Kristofferson was a true Renaissance man in every sense of its meaning. The West Point graduate and Rhodes scholar was also an Army Ranger and helicopter pilot blessed with a profound knack for prose who unexpectedly abandoned a promising military career to make it in country music. To his entire family’s chagrin, he took a job as an overqualified janitor for Columbia Records’ Studio A in Nashville, which had been previously known as Bradley Studio B (aka the Quonset Hut), in 1966. He’d arrived in town a year earlier after his discharge from the Army and, after signing on with Marijohn Wilkin’s Buckhorn Music, made an impact with his patriotic song, “Vietnam Blues,” which addressed the growing overseas conflict that was beginning to cause division back home. The relatively unknown Jack Sanders was the first to record it for Dot Records in August 1965 but was taken the #12 C&W spot about six months later by the better-known Dave Dudley.

It was a good start but chasing that second hit proved elusive and Kris hit a drought. He found solace hanging out with a group of fellow fledgling young songwriters like Vince Matthews, Shel Silverstein and Mickey Newbury, improving his craft and immersing himself in the growing counterculture movement. He also hobnobbed with more mainstream players, like Waylon, Willie, Roger Miller, Dallas Frazier and others, at music insider Sue Brewer’s Music Row apartment. It was an after-hours haven for young musicians who she often befriended at her late shift at the Derby Club a mile-and-a-half away. Naturally, Kris was initially sheepish with this talented crowd that occasionally featured heavyweights like Webb Pierce and Faron Young.

Waylon was the one he stood in awe of though. Even though he was far from the household name he’d later become, Waylon exuded a cool confidence that was intimidating and seemingly impenetrable. In fact, Kris was so mesmerized by Waylon that he often pitched songs to his drummer Richie Albright, a fellow longhair around whom he was much more comfortable. He scored big when Waylon brought his song “No One’s Gonna Miss Me” to a November 1967 session with Anita Carter, which ended up as the B-side to their Top 5 C&W single “I Got You.” Though far from Kris’ best work, it set off a chain of hits for others beginning with “Jody and the Kid” hitting the Top 25 C&W in the summer of 1968 for Roy Drusky and growing bigger and better with “Me and Bobby McGee” by Roger Miller, “For the Good Times” by Ray Price, “Help Me Make It Through the Night” by Sammi Smith and “Sunday Morning Coming Down” by Johnny Cash.

Waylon would record his fair share of Kristofferson songs in the early 1970s and found his own approach to songwriting greatly influenced by his new contemporary’s more mature style. Overnight, Kris changed the country music industry and laid the stylistic blueprint for Outlaw country with a gritty realism more akin to Bob Dylan than Hank Williams. Waylon and others felt freed from the heavy thumb of the outdated Nashville Sound, which was sounding more and more like elevator music. But it would still be a couple more years before Waylon fully broke free from the executive shackles of RCA Victor.

Toe the mark and walk the line

It’s been misreported that Waylon struggled immediately upon his arrival in Nashville in 1965. Though hit didn’t knock it out of the park right away, he was a regular Top 10 C&W contributor by mid-1966 and had won a Grammy in 1970 with his cover of Jimmy Webb’s “MacArthur Park” with the dual husband-and-wife singing team, the Kimberlys. But it was never as good as it could’ve been, and he was always in search of that one song that would take him over the top. He had a unique sound that was thumping, throbbing, more Bakersfield than Nashville, and devoid of twin fiddles and steel guitars. Chet Atkins and the Nashville studio system refined it all sometimes for better, other times for worse. This sound was present in early hits like “Stop the World (And Let Me Off)” and “Mental Revenge,” but it wasn’t building his brand well or leaving the mark on country music that he wanted. That started to change around three years into his RCA tenure.

In 1968, he released a song called “Only Daddy That’ll Walk the Line” that arguably lit his fire and laid the blueprint for what would be referred to as the Outlaw sound. It reached #2 on the C&W chart was unlike anything he’d ever recorded or occupied the upper reaches of the Top 10. It leaped out of listeners’ speakers like a jackrabbit and bounced around the eardrums with beautiful reckless abandon and contained a guitar solo that was uniquely Waylon and a harmonica that prefigured Willie Nelson’s work with Mickey Raphael. It was Outlaw before it was a thing and bolstered his standing by adding shows to a seemingly endless tour. But he couldn’t build upon it, and it would be six years before he eclipsed that song’s chart position. Of his three next single releases, the highest position was #19. Even his Grammy winner, “MacArthur Park,” only reached #23 in late 1969. Success was having the opposite effect.

By 1972, Waylon was worn out both physically and emotionally. His struggles with moderate chart success, his label, the studio and mounting debt had taken their toll on his spirits, and he was laid up in bed with Hepatitis B, which he’d contracted after playing at an Indian Reservation in New Mexico. His original drummer Richie Albright had recently rejoined his band after a three-year hiatus and saw the terrible condition his old friend was in. In fact, it was so bad that Waylon was considering leaving Nashville altogether and rebuilding his career in Phoenix. Richie knew Waylon’s potential better than anybody and convinced him to talk to a business manager he knew named Neil Reshen. He’d gotten to know him during his hiatus when he’d been a roadie for the Phoenix area country rock band Goose Creek Symphony who was signed to Capitol Records. They were hardly known outside of Phoenix, but Reshen’s persistence and demeanor had the label pampering them like they were the Rolling Stones. It was the fruit borne of managing stars like Miles Davis and Frank Zappa. Richie believed the time was right for big time country stars to be treated with the same respect and felt that Waylon and Neil were a perfect match.

Waylon agreed and the two met a few days later in Nashville. The Jewish accountant from New York made such an impression on the cash-strapped singer that, afterwards, he even recommended him to Willie Nelson who was struggling with pretty much the same things. He immediately went to work and put RCA and Waylon’s booking agent, Lucky Moeller, on notice. He wanted to go through their books and account for dollar spent, right down to the penny, to make sure his client wasn’t getting ripped off. At a meeting with Chet Atkins and other label executives in the fall of 1972, Neil quickly went into overdrive. He raged and accused them of stealing from Waylon and holding him back, telling them they treated him no better than a run-of-the-mill new signee with a lousy royalty rate, which was undermined by the studio costs they heaped upon him. The goal was to get his client creative autonomy and put him in charge of his career’s direction because they sure weren’t hitting the mark. It was fierce, quick and effective. Waylon walked out with an advance, a royalty rate and creative control the likes of which no country artist had ever seen before. For Waylon, the biggest outcome was that he was now in charge of his own music’s production, which is what he’d always wanted. He could bring his band into sessions, which was verboten, pick what songs to record and even have final say on his album cover and he found success almost immediately. Every musician who rises to that level believes he or she know what’s best for them, but in Waylon’s case, it couldn’t have been truer. Beginning with his first self-produced venture, “You Ask Me To,” released in September 1973, Waylon became a fixture in the C&W Top 5, including his first #1 hit, “This Time” in 1974. He also released the groundbreaking LP “Honky Tonk Heroes” in 1973, which went gold and has gone on to become one of the most celebrated albums in country music history.

Lucky Moeller was next. He’d acted as Waylon’s manager and booking agent since his arrival in Nashville seven years earlier, but, although he was kind and lovable, he’d basically made Waylon his indentured servant. By the time Neil took over as Waylon’s representative, Waylon owed Moeller $50,000 in back commissions because of questionable but legal business practices. Turns out, Moeller never charged any venue more than $1,750 per night for Waylon and the Waylors’ services and he was often used as a loss leader. That means at gigs where he was the headliner, his rate was discounted for the promoter so that he’d take another one of the agent’s acts. That’s understandable for a new act trying to build an audience, but, at this point, Waylon was seven years in and should be commanding a greater price tag. Moeller, who had seemingly had a monopoly on Nashville talent, never really thought beyond the regular country venues. If his artist played Las Vegas, it was the Golden Nugget. In L.A., it was the Palomino Club. In New York, it was the Nashville Room in the Taft Hotel or a suitable country and western club in New Jersey. There was no help on the road either. Waylon and his band were on their own in terms of getting from gig to gig and hauling their equipment in and out of each venue. All this and Moeller’s 15% commission resulted in Waylon always being in mounting debt and it was all fashioned into his RCA contract.

With the new contract, Moeller was put on notice and his commission was reduced to 10%. And now that Neil Reshen selling Waylon’s services at a much higher price, a plan was put in place to pay off the Moeller Talent Agency in three years and move on from them permanently. Neil’s strategy was revolutionary in country music terms and that’s where Max’s Kansas City came in. It was wild, daring, unorthodox and a no-brainer as far as Neil Reshen was concerned and would kickstart his new client’s reputation as one of the top live acts in country music and beyond. Waylon was a little more hesitant.

Back to where it all began

To call Max’s crowd hostile would be wrong. They were a little confused, but they were also draped on all sides the first night by RCA Victor brass who came to see what the fuss was all about. Waylon was a little befuddled by the club’s layout and even the bizarre name. There was no one named Max and nobody with any ties to Kansas City. Owner Mickey Ruskin, a veteran Greenwich Village club owner with a law degree and a love for art, thought Max’s was an attractive name for a club and believed that Kansas City was the height of fine dining as he’d always seen “Kansas City steaks” on menus when he was a kid. He opened the two-story club, previously occupied by the Southern Restaurant, in early December 1965 and attracted a sizable art crowd. When Andy Warhol started hanging out there regularly after the New Year, it became one of the hottest clubs in town and impossible to get into after 9:00 pm. The avant-garde artist held court each night from midnight until dawn from a big round table in the back room that more resembled a dark room because of its red fluorescent lighting compliments of fellow artist Dan Flavin.

Walking into the place was like entering into a smokey tunnel with modern art decking the walls and young art types in sunglasses, ranging from awkward looking to model beautiful to transvestite. The first floor was indeed a restaurant, covered in tablecloths and silverware, and serving mostly fish and steak with chickpeas. The music was upstairs and that’s where Waylon headed followed by a crowd of mostly young and curious art and music lovers. And that’s when the “Who the hell are you” question flew out of the ether from a female audience member on opening night. Surely, Waylon was at least a little taken aback. Who the hell were they? He’d been through the ringer for well over a decade, beginning right here in Greenwich Village when he slept on Buddy Holly’s couch for a couple nights less than a mile away nearly 14 years ago to the date. Buddy used to tell him about the kooky Greenwich Village clubs like the Village Vanguard and the Five Spot. Less than three weeks later, his world was turned upside down when Buddy was killed in a plane crash outside of Clear Lake, Iowa, along with singers Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper, after trying to get a jump on the next venue. The touring conditions were wretched and freezing. Waylon was supposed to be on that plane but a gracious gesture to an ailing Bopper prevented that. God wasn’t quite done with him and, after what must’ve felt like 100 years later, here he was back where it all started. His own introduction to the Max’s Kansas City crowd was equally provocative.

“I hope you like what we do,” he said to that young girl and others gathered in front of the stage. “If you don’t, don’t ever come to Nashville. We’ll kick the hell out of you.”

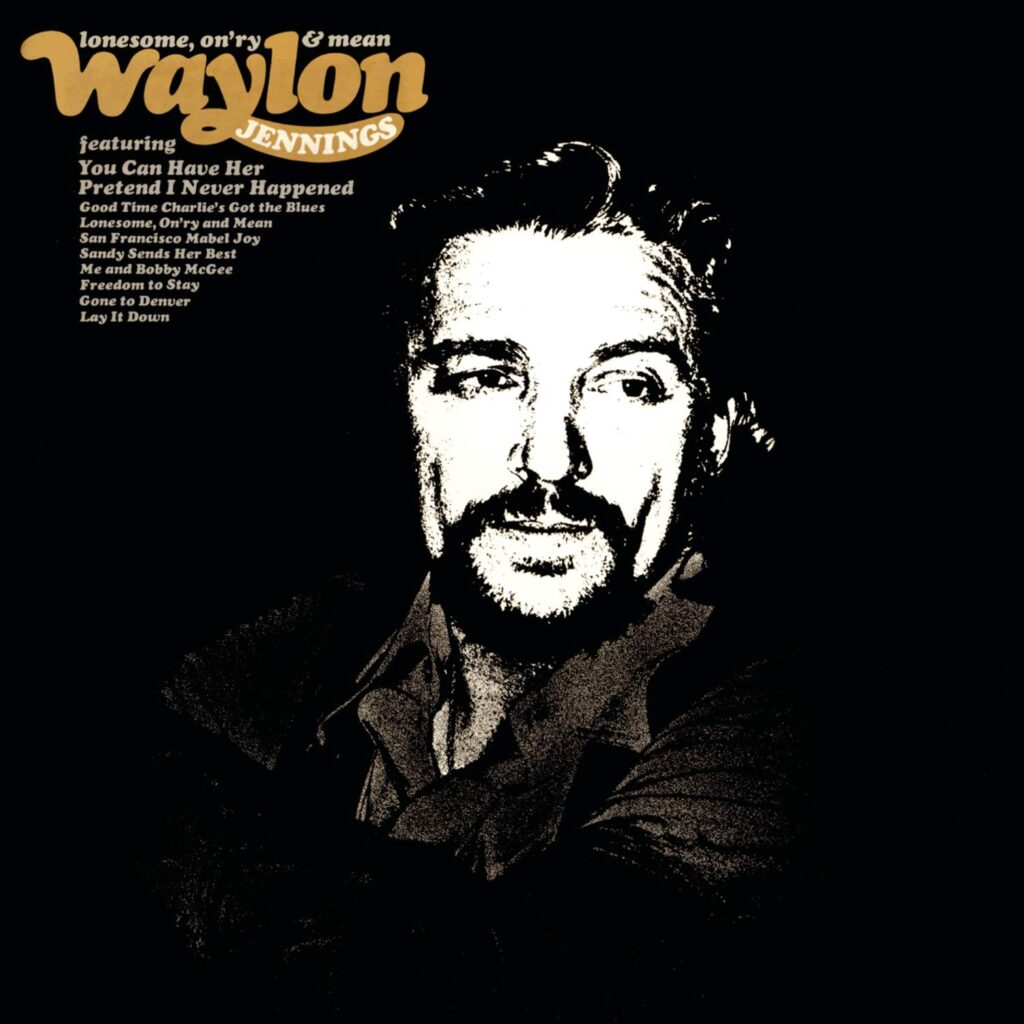

Outlaw was born! It’s one thing to say that in one of those buckets of blood in Texas, but New York City was something else entirely. The country singer was supposed to be the odd man out trying to curry favor with the self-proclaimed cultural elite, not be antagonistic. But this crowd, used to aggressive artists like Lou Reed and Iggy & the Stooges, ate it up. They embraced Waylon’s authority, particularly after he dazzled them with his four-on-the-floor approach to country music, present in songs like “Lonesome, On’ry and Mean,” Good Hearted Woman” and “Me and Bobby McGee,” augmented by the more somber “Good Time Charlie’s Got the Blues.”

Waylon’s stand was a hit. Not only did the audience love him, but the press who’d attended heaped praise on his performance. Penthouse Magazine reported that Waylon “stomped the shit out of Max’s.” The British magazine New Musical Express proclaimed, “country meets rock, and everybody wins.” Even Nashville got behind their former outside when Peter McCabe of Country Music Magazine stated that it was “a major breakthrough” for country music. The game was on now. The fruit of Neil Reshen’s work was growing on the vine. Waylon was the water and Willie Nelson would eventually provide the sunshine.

This incredible stand would be followed by another successful one in the much more country music friendly Troubadour in Los Angeles and the release of his “Lonesome, On’ry and Mean” LP in March. It was the first time the country music fans would see a bearded Waylon Jennings on the cover. The usually clean-shaven singer had first grown it during his bout with hepatitis. It’s hard to believe now because it became his trademark look, but it took a while for his facial hair to fully grow in and once it did, it stayed. Gone were the days of his slicked back, Carl Smith pompadour and Waylon would become fully immersed in the hairy 1970s. Along with Willie Nelson, he went on to dominate the decade and fulfill the promise first recognized by Bobby Bare, Skeeter Davis and Chet Atkins eight years earlier. Nearly every single he released through the remainder of the decade hit the Top 10 with 11 hitting the #1 spot.

Reaching the top didn’t come with its drawbacks for Waylon. His amphetamine addiction would morph into a full-blown cocaine addiction fueled by endless nights at Hillbilly Central, a small but revolutionary Music Row studio run by country music veteran Tompall Glaser, and would take a tremendous toll on his health. But that’s another story for another time. In early 1973, Waylon Jennings stood on the precipice of country music domination and the world was his oyster.