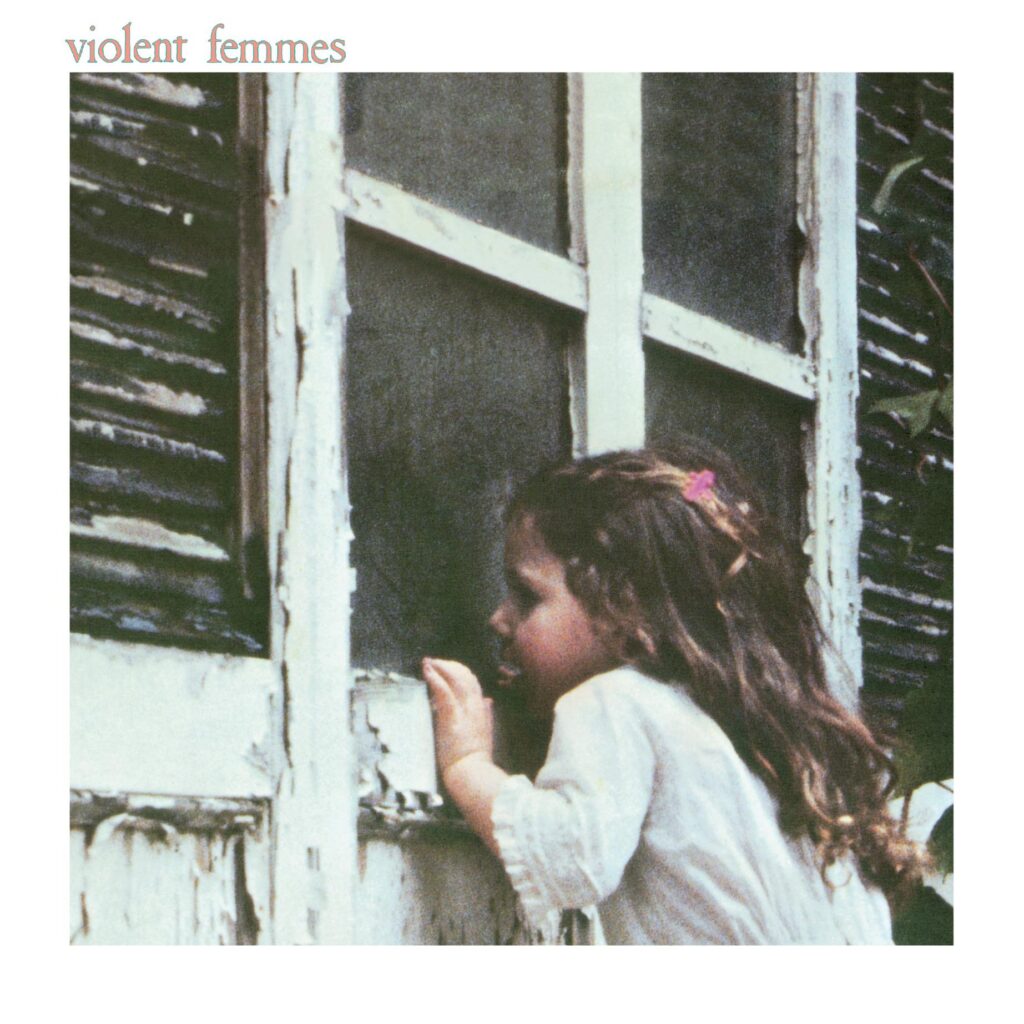

Violent Femmes (Credit: George Lange)

By Jason Barnard

Victor DeLorenzo, founding member of Violent Femmes, reflects on their classic debut album. Their self-titled LP features unforgettable songs like ‘Blister in the Sun’, ‘Gone Daddy Gone’, and ‘Add It Up.’ Victor explains its enduring significance, the band’s early struggles, its recording, success and legacy.

The Violent Femmes debut has grown in stature over the last 40 years. How does it feel looking back?

It’s surprising. When we made the record, we knew that we made the record to the best of our abilities when we recorded it. But of course, in our wildest dreams, you never realised that 40 years on, we’d be celebrating it this way.

I’m proud of that record. We worked very hard to put that record together. And through the auspices of my father lending us $10,000 to make that record, that’s the reason why you can hold that 40th anniversary vinyl box set in your hands today.

Absolutely. I grew up with indie discos and ‘Blister In The Sun’ was played every night. Is it the same in the States?

Once it caught on, it got quite a bit of airplay, especially on college radio. Now the interesting fact about that song is that in a lot of sporting events here in America, when they’re going from commercial back to what’s happening when they are going from the sporting event to the commercial, they’ll play ‘Blister In The Sun’ as some bumper music. So that’s always surprising to me when I’ll be watching a Brewers baseball game and all of a sudden I’ll hear myself playing the snare drum.

There’s various packages of the reissued album, including a 4LP vinyl box set. Have you seen them?

I really love the vinyl box set, which is released today, March 1st, here in the States. But I think it’s absolutely brilliant, the design of it, the quality of the vinyl, the incredible pictures from George Lang. And I must say, the liner notes that David Fricke wrote, I’ve been suggesting to Craft that they should definitely nominate him for a Grammy for those liner notes. I think they’re fantastic.

There’s quite a few extra tracks. Is there anything that’s caught your attention?

Well, that’s all from my archive. So I knew all that material pretty well. I’m glad that we could give that to the Femmes because everybody always likes to hear something a little bit different from their favourite group. So what better place to put it than in this box set that’s absolutely incredible.

Take us back to the early years of the Femmes and the run up to the recording of your first LP. What was going on in that period?

We were trying to play as many live shows as we could, trying to sell the record. We made the record, as I said before, because my father was generous enough to lend us $10,000. So we were creating the master recording on our own.

We weren’t hired or under the auspices of any record company at that point. So after the record was finished, it was our intent to sell it as a finished master, which is exactly what we did when we sold it to Slash.

But before it got to Slash, I have a drawer full of a ton of rejection notices from different record labels saying that ‘we don’t understand this music at all. We don’t know how it fits into what’s happening in modern music now. We’re just not interested.’ But fortunately at Slash Records in Los Angeles, there was a woman who was an A&R named Anna Statman, and she really went to bat for us. She loved the record, and she kept hounding Bob Biggs, the president of the label. “You’ve got to listen to this record. We have to sign this band. This is something new and unique, and I think it’ll be really good for the label.”

It turns out all these years later, I’ve talked to people that had worked at Slash, and they told me that if it wasn’t for your record, the Slash Records company probably would have gone under. Our record was so popular and sold so many. It was the best selling record on their label.

Who was it that championed the music? Was it the college kids?

College radio really had a hand in making the Femmes famous because they not only played things like Blister, more of the acceptable known songs from us, but they went deep into the records too and played other cuts as well. So we were very thankful for that. Also, a lot of our first touring when we started to make some real money was through the college circuit. So, Violent Femmes are indebted to college students and colleges everywhere.

Is it true that The Pretenders had a hand in helping?

Well, it’s a nice story. They helped in that they added to our myth. But the honest to God truth is, when we opened for them at the Oriental Theater here in Milwaukee, they had seen us busking on the street and they asked us to open the show for them.

We didn’t know who The Pretenders were because we were totally into avant-garde jazz and rural country music and world music. So we weren’t up on the modern scene. So when they asked us to open, we said, “Yeah, sure.” But we were thinking, “Is there gonna be anybody here tonight or anything?” So we went and played with them. They let us play three songs. And it was really fun, but the next day we were back out on the street.

So it was more like a Schwab’s drug store, kind of a Hollywood story. It didn’t really help us as much. What really helped us was a few months later, we went out to New York and we played at The Bottom Line and there were incredible reviews of that show. That’s what really started our life as Violent Femmes.

What were your influences in music and as a drummer?

As far as music was concerned, I really wasn’t interested in any kinds of music until I was about maybe 14 years old. Up until that point, I was very interested in theatre and film. So to me, music was something that was just part of theatre or film. I wasn’t paying attention to popular music at that point in time. And then came the one summer Saturday afternoon, when I went over to my cousin Chris’s house.

He said, “Hey, Vic, I want you to come into the basement. I want to play you a new record I got.” I said, “Oh, okay. What’s it gonna be?” So he played me Hey Jude by the Beatles. And after I heard that, my mind was twisted. I didn’t listen to anything but the Beatles for the next six years. That was my main influence, as far as music was concerned. But when you got down to drumming influences, because I was studying with a jazz teacher, all my drumming influences were all from jazz musicians.

So that was my kind of sandwich that I was putting together. Really enjoying all kinds of pop music after being led into the fray by the Beatles. But then continued my education of jazz drumming, which eventually led into appreciating people like John Densmore from The Doors and Ringo Starr, of course, and Charlie Watts. The list goes on and on and on.

But from the beginning, like I said, the first six years, I was a Beatle fanatic. I don’t want to hear the Stones. I didn’t want to hear Canned Heat. I didn’t want to hear Creedence Clearwater. I didn’t want to hear anybody except the Beatles.

In the run up to the album, what were you guys listening to?

We were listening to everything from early country music, Louvin Brothers, Johnny Cash, and then we were listening to more avant-garde jazz things like Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, some of the Charles Mingus stuff, the Art Ensemble of Chicago. Then we were into things like the Velvet Underground, Nico, John Cale, all the usual suspects in that realm. We were hip to all those people.

Your drum setup is unique and comparatively minimalist. What was the reason for the setup?

One of the nice things about working with Brian and Gordon is that they allowed me to innovate. So I could go out on each tour with a different drum system that I would come up with. But I think what I’m mostly known for is what’s on the first album, where I’m playing a Gretsch snare drum, a folk art instrument I invented called a Tranceaphone and a cymbal.

That was my little setup on that album. Even though on a song like ‘Good Feeling’, I did play a sit down drum set. Most people don’t even realise that. But all throughout our touring days, I was always fortunate because I could, if I was interested in saying, playing a stand up drum set with a sit down drum set, I could have them both there.

So I could start a fill standing up on the drums and then proceed to sit down and finish the fill. So that added to the showmanship aspect of it. Also it just kept me interested in trying to redevelop and re-present the music in new ways.

What are your memories of recording that album? Was it a quick process?

Well, the recording itself wasn’t that laboured. We were working at the studio in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, which is not too far from Chicago. We didn’t know at the time that this studio called Castle Recording was going into receivership when we were there. So we would show up for sessions that we had paid for, and we’d noticed that bits of equipment were missing, and they didn’t really have a real good explanation why the equipment was missing and all that.

Then one day we got assigned a different engineer, and we later found out that that engineer was the janitor. So the janitor engineered us, a guy named Glenn Lorbiecki, nice guy, a little bit over his head. He knew a little bit about recording, but he was mainly the janitor. So anyway, we recorded the record with him, but then we mixed the record with a good friend of ours, John Tanner, who was a bona fide recording engineer.

But it’s funny, because I don’t know if this exists anywhere else in music history, but this fellow, Glenn Lorbiecki, that did the recording, the janitor, he’s got a platinum record for engineering that record that he probably never should have been anywhere near. [laughs} I love that story.

That’s amazing. When Gordon brought songs to you and Brian, how did that work?

Gordon had an infamous notebook that he had been keeping track of lyrics and chord progressions and melodies and stuff for some time. So when we met him, he had a lot of songs already written that would come to appear on the first and the second album.

So we just really responded to his material and thought that it was something to get behind because Brian and I were also songwriters and multi-instrumentalists. So at first we had thought, well, maybe we would be the Beatles and we would all contribute music.

But after a short amount of time, we started to think, well, maybe it’s better we just back Gordon’s material because he has so much of it and so much of it is so good we were discovering. So the main jobs then that fell on Brian and I’s shoulder were to be arrangers because we’re very good at thinking about how structures of song should go and if things should be added or subtracted, arrangement ideas. That’s something Gordon didn’t really have. He would just present us the raw material and then we would shape it into the music that we all know today.

Were you taken by surprise after the album’s release? It got critical acclaim and then it started selling, which must have been surprising given that you weren’t on a major label.

Slash was a pretty well regarded label in Los Angeles, and eventually it became part of the Warner Brothers family. We were happy that it was popular. That’s why we made it. We wanted to be able to make more records and also use that record as a calling card so we could get a record deal and also a booking agent and be able to play not only in America, but try to get on into other parts of the world.

A number of the tracks from that album have been featured in TV shows and films. That must always be a buzz when it gets picked up in a film like Reality Bites, for example.

Right. You have to see how it’s used in the film. I know they had used one of our songs in that film about Tanya Harding called I, Tanya. And then just recently there was that film called Air about Michael Jordan and the Nike basketball shoe deal.

And they used two of our songs in that film. They used ‘Blister’, I think, and they used ‘Good Feeling’. So it just shows that the songs are popular enough now that enough people know them that if they put it into a film, people will realise what it is.

Do you think it’s the simplicity of the material that gives it a timeless appeal. The songs don’t date like some of the most synthesiser heavy acts of the 1980s, the gated drums and that sound.

We designed it in a way without having any kind of educated thought to make something that will last forever and will never sound dated. The thing that Brian and I wanted to get across was at that time of making the album, really into the rhythm section of Gene Vincent and the Blue Caps. So we wanted to bring that kind of energy and that ferocity to what we were going to record. Not that we thought we really sounded like the Blue Caps, but we love that energy that they had in their records.

But it has turned out to be a timeless record in that even though it depicts a time in the early 80s when everything, as far as what else was going on in the music world, everything was against us. We had nothing to do with hair bands and we weren’t disco. There was so much anti what we were doing that I’m surprised that it did catch on. But probably the reason why it did catch on, was because it was so different and the material was good. Gordon was writing material that would be passed on from generation to generation, almost like a rite of passage.

Where do you think that album stands in the next decade of material when you were in the Femmes?

I have an approach that I’ve heard other people mention in the past, too, in that I look at all the records as one record. It’s hard to separate them from me, and I know you have to do that for commercial reasons. But for me, I always looked at all the music as being a collection of music. So I didn’t really break it down so much in my mind. And in that way, I have certain favourites from all the records that if I put together a compilation, it would feature a lot of different materials.

Looking more broadly, I know that you’ve released your own material. What are your current activities in music and the arts?

Right now I have a group with Janet Schiff, she’s a cellist who also works with a looper and another fellow named Matt Meixner who’s an incredible keyboard player. And so we have a trio together called Nineteen Thirteen because 1913 was the year that Janet’s cello was made in Transylvania.

So we’re primarily an instrumental group but we also have some songs with lyrics. We’re in the process right now of working on a new five-song EP. I think we’ve released about five records now.

I’m also an actor and I just finished work on a film that has just been submitted to all the different film festivals around the world. It was made here in Milwaukee by a filmmaker by the name of Eric Engelbart. It’s a short film, only a half hour long but I’m very proud of that. I started my career in show business as an actor. So I’ve kept that up all the while that I was in Femmes and when I’ve been out of the Femmes.

Thank you, Victor. I’ve loved going back to that album. As you said, Gene Vincent is a great template. It’s one of the things that means that the album will just keep on being heard and being repackaged.

Probably long after Iong after I’m gone. Thank you.

Further information

Violent Femmes’ 1983 self-titled debut reissued: The deluxe 2-CD and digital formats feature newly remastered audio and over a dozen demos, B-sides, and live performances. The 4-disc vinyl box set is limited to 5,000 copies worldwide. This collectible edition offers three LPs — the original album, alongside the demos, and live material — plus, a replica 7-inch single (“Ugly”/“Gimme the Car”)

Victor DeLorenzo 2020 Strange Brew Interview

All photo used with permission.

I love the Violent Femmes and I just recently saw them in Austin Texas and they were just as amazing as they were when I saw them in Chicago in 1996!