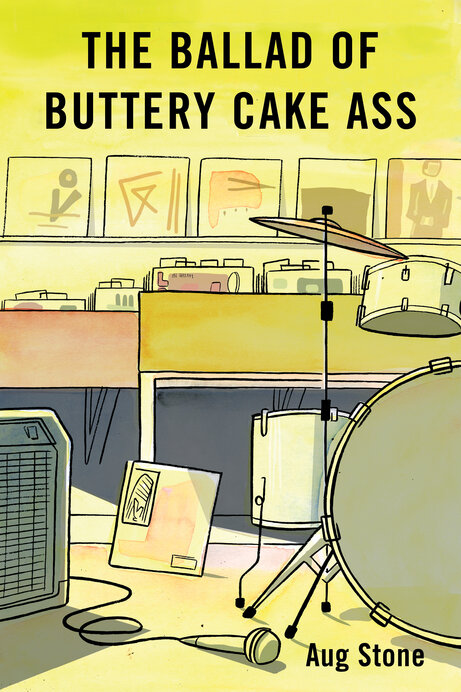

Aug Stone

By Aug Stone

When we were 15, my best friend and I used to make up fake bands to ask for at record stores. We thought this was hilarious. And still one of the funniest things I’ve ever heard in my life was, one day in 1991, at Cutler’s Records & Tapes in New Haven, Connecticut, hearing him ask the clerk if they “have anything by Buttery Cake Ass?” The clerk genuinely wanted to be helpful, after all there were a lot of strange band names floating around back then – Poi Dog Pondering, Ned’s Atomic Dustbin, Meat Beat Manifesto – and so he asked us “Is there any particular album you’re looking for?” Without missing a beat, I said, “Live In Hungaria”. At which point he looked even more puzzled. “Do you mean ‘Live In Hungary’?’ And we both shook our heads no, deeply serious, “It’s definitely ‘Live In Hungaria'”. As he walked away to go look for this album that did not exist, it was a feeling of utter, absurd, joy. This book, The Ballad Of Buttery Cake Ass, is an attempt to recapture the comedy of those days, before irony really set in around 1994, as well as relive the excitement and anticipation one would feel in the pre-internet era, where it could be weeks or months before you got to hear a band or record after learning of its existence.

“The second tune, what ends up being A Real Fridge In Real Life, takes a rather convoluted journey. At least title-wise. You see, Hans Floral Anderson had this idea. He’d heard the story about The Clash’s version of Armagideon Time. How Kosmo Vinyl thought the perfect length for a single was 2 minutes 58 seconds, and so the group asked him to stop them when they got to that point. Look it up, there’s all that banter on the track. Not that A Real Fridge In A Real Life sounds anything like Armagideon Time. According to Reg Button, anyway, who is tasked with halting the band when the clock reads 3 minutes and 14 seconds. Which, knowing the Clash story, he does not do. But we’ll get to that…

The music did come about from just a song length though – yes, the aforementioned 3 minutes 14 – and is one of the first tunes they write with Blish. The perfect duration being a concept Hans Floral Anderson expended much mental energy upon. He considered 2:47 hard to beat for sheer aesthetic enjoyment, and of course the 3:33 trio of threes is pretty near immortal, except for the radio station standard of fading out at 3:30. 3:17 also has its own power, adding up to 11 as it does. It is no coincidence that 2:22 looks like a bevy of swans, for to contain a song within such short limits requires much grace and authority. 1:11 even trickier, but those upright numbers, resembling candles as they do, provide a beacon, brought all the closer by the explosion of punk rock. The day it finally comes to him, the group are standing around Graph City passing the import 12” of that first Cure record, Three Imaginary Boys, back and forth. The very real young men in the record store intrigued because when it was released in the States, the album had a different track listing and the title of Boys Don’t Cry. They huddle over the sleeve, trying to figure out if the band are actually sobbing or not, and, as always, on the lookout for ideas to make into songs of their own. Someone soon putting forth – ‘What would it sound like if we, Buttery Cake Ass, were in the refrigerator on the cover of this record?’ An intriguing proposition…

Hans holding the album a bit too long in his hands and starting to giggle. ‘What if it was like a magic ice box…and turns us into pie?’ Quickly snapping his fingers. ‘We should do a song that’s 3 minutes 14 seconds long!’ They immediately write down that tempting song length, its temporary title just those three numbers. One digit separated from the other two by a colon, much like how a digestive tract would work in relation to Buttery Cake Ass’ name.

Walter overhearing the whole conversation, now signals for them to hand him the record, dropping the needle on the song So What?, one of the tracks deleted from the US version. Watching mirthfully as the boys’ eyes pop out at all the talk of cake in the lyrics. Which spurs them on in their intent for the new song, that a tune entitled 3:14 must be fated or something. The Cure offering them this refrigerator to crawl into and dare being somehow distorted into another dessert. Davey Down pointing out that the Cure themselves are almost a pi. Though with a slice taken out, making them only this fictional trio, three imaginary boys. Not that pi is an imaginary number, Davey clarifies. He had learned that at school.

After Cookie writes Hans back how annoying it is for him to keep referring to a song by only its time value, the boys start calling 3:14 ‘Magic Box’. Though they soon deem this title too risqué and thus begin writing it on the rehearsal set list as Buttery Pi Ass. Which really seems to sum it up. And is something Cookie has no response to. Then someone got lazy. One practice it is written with only a single S, reading simply PI AS. A mistake surely, but once again tying them to the great cinematic tradition. Those four letters standing in some circles for ‘Play It Again Sam’. What he doesn’t actually say in Casablanca…

It isn’t until quite late in the game that the title is switched to what would wind up on the album – A Real Fridge In Real Life – with Brouce Cozzins, more on him later, Brouce Cozzins The Second obviously, initiating the fateful change. Brouce digs the concept behind the song, the Cure transforming this band from cake to pie like that, but feels a certain compulsion to suggest that while theme songs are always cool, this one is a bit confusing. Especially as it isn’t, in fact, a theme song. With a debut album, clarity of vision is what is needed. Hans realizing that they haven’t come this far in shaping their sense of identity only to jeopardize it with delusions of doppelgängers. And besides, with the 3 minutes 14 seconds listed on the sleeve, listeners might figure it out for themselves. Making the reference even more pure.

As it happens though, no one gets it. Not Brouce Cozzins The Second, not his father, not anyone. Being as, just like with the Clash, you can’t stop time. No matter what Cher might have you believe. I assume you would have to stop time first in order to turn it back, and anyway Cher was gettin’ ready for her acting career at this point. But like with the Clash – and as far as I know there are no films starrin’ both Cher and The Clash, closest we get are the lyrics to Rock The Casbah – but the Clash couldn’t be stopped in time either, even with the word ‘time’ in the very title of the very tune they were tryin’ to record…”