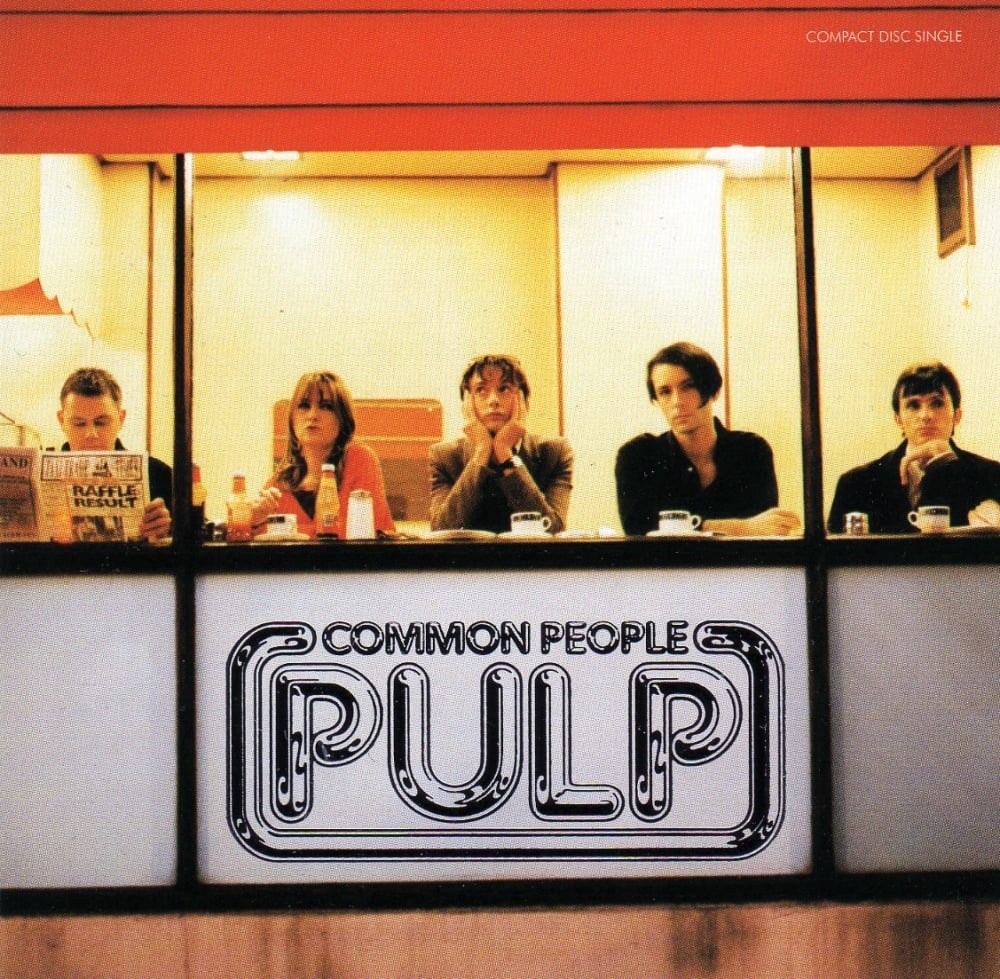

Pulp’s Nick Banks speaks to Jason Barnard, delving into the inception, recording process, influence, and legacy of the iconic ‘Common People’.

What sets Jarvis Cocker’s lyrics apart is their observational style.

When you move to London, you do meet some characters. And certainly as we started getting around a bit, you did start to see them. Obviously Jarvis was at St Martin’s Art College, which was full of people dressed as Christmas trees and that kind of thing, so it was all a bit different. And what I found when I moved down to London is that you feel that connection to the place you’ve come from and you see it in a different light and it affects you in a different way. And so maybe you see the strange stuff of Sheffield through the prism of not being there as something maybe more worthy of talking about, perhaps.

Because you then know what makes Sheffield unique because you’re not there.

Definitely. You look back to it and you think about the characters perhaps you’re meeting in London and reflect them against perhaps the characters you knew from Sheffield. Often they can be very different. Going towards the character in ‘Common People’, the Greek girl feeling that people are slumming it a bit, hanging out with kids who’ve actually got no money, just because it’s just a bit daft. You did meet those kinds of people who didn’t have to live in a squat but thought, hey, I’m going to be edgy and live in a squat, but didn’t really have to.

For Different Class you worked with Chris Thomas, who’s got a massive pedigree in the industry.

Absolutely. I think once we’d done the His and Hers album with Ed Buller. When it was time for the next record we knew hopefully, that it was going to be a step up, it was going to be seen and reviewed eagerly. So I think we thought, well, Ed did a good job, but perhaps it was maybe a little bit too reverb, a bit too echoey etc. So we thought, well, we’re going to have Island give us basically as much money as we want to record it, so we can get someone who’s going to really do an interesting job. I remember a few names being bandied around, as well as Mr Thomas. There was Jeff Lynne, he was talked about for a bit. Vince Clarke of Erasure, he was talked about. We’d done some tracks with Stephen Street, who did the Blur stuff. He was obviously the mid 90s go to young bloke, he was in the frame, there were quite a few. In the end we went with Chris Thomas because we looked at the songs he’d done in the past and we just thought he knew what he was doing. And a very interesting bloke. Looked a bit like Mick Fleetwood.

Big, big sound, though.

Big sound. Big studio, yeah, big sound. The kitchen sink is there on Different Class. There were times when you thought you’re going to be in a 24 track studio, sod that! Let’s go 48 track! Oh no, that’s not enough. I think we ended up with like 72 tracks on there, something absolutely crazy like that. But, everything goes on there. That’s one of the great things about going in the studio, is that when you’re writing and you’re rehearsing up the songs, all you hear is guitar, bass, drums, keyboards, mumbled singing, you never even hear any words. But then you go into the studio and you lay the basics down and then you start hearing the words. Then all the other stuff gets added that beefs the sound up. The little bits that folk think of and that all adds to it, you see the development of the overall sound and that’s the really exciting bit. And certainly hearing the words. We knew the song was called ‘Common People’, but you never heard any words because all you got was [mumbling] Jarvis working out his melody rather before thinking of the actual words. But then in the studio, you hear the words come out and you start thinking, yeah, this is getting really interesting.

One of my favourite bits about the recording of ‘Common People’ was doing some mixing or some overdubs and stuff like that. We were all sat in the studio, lolling around, reading the paper, being deeply bored. The doors were open, and someone was out in the corridor with a Hoover. Hoovering up. Mr Thomas took umbrage, and suddenly stormed out the studio shouting this thing, “We’re trying to make a fucking hit record here!” and slammed the door. We were all perked up from our newspapers going, “What was that?” And he sat back down, pressed play, and it sort of really hit home that, yeah, you were making a hit record. And it was kind of quite an amazing realisation that although the record wasn’t finished, it was going to be a hit record. That was quite an amazing moment, really.

‘Common People’, of all the songs on Different Class, is one that has such a driving sound. It’s not complex musically, but it kicks.

Well, that’s it. Because I would like to say one of my styles is not adhering to perfect time. Some would say that’s a flaw in a drummer. I would say it’s a requisite part, because it gives you the excitement of the track. We tried doing it when we recorded at a constant tempo. So we decided to start at the start tempo and keep that going throughout the song. And halfway through, everyone was falling asleep, it was so dull. So we thought, all right, well, that’s no good, so why don’t we try at the end tempo? And it was like, my god, this is starting so fast. We couldn’t handle it. So we thought, alright, that’s no good. We tried the middle tempo and it just didn’t have the drive, it didn’t have the excitement, didn’t have that feeling of almost like a runaway train, the feeling that the excitement builds and builds, and it comes to the crescendo. You had to use a click track in your headphones to record it so that all the electronics could be fixed onto it as well in the correct time. And so we ended up starting at my start tempo and mapped it out so that the beats per minute gradually got higher and higher throughout the song so it mapped exactly. I would play it without any click track in the headphones, how would I play it normally. And that’s how we ended up doing it, because it gave it its excitement, gave its rush. That’s how we had to do it.

It’s a contrast to popular music today. But when you look at ACDC and Phil Rudd, or John Bonham and Led Zeppelin, and you track the speed of the drums, it fluctuates. But that’s what gives it its soul.

I think it gives songs a sense of excitement, a sense of, this is something to get excited about. So I’d like to take the credit for all that. Thank you.

It was massively successful. Also such a contrast headlining Glastonbury when you were struggling to fill a pub five or six years before.

Absolutely. You’re right. The story of how we got Glastonbury is quite well known. But thank you, John Squire, for falling off your bike and busting your collarbone. I will forever be grateful for him doing that. We got a chance. It’s not every day you get a phone call from someone saying, “Yes, do you fancy headlining Glastonbury on Saturday night.” “Erm, yeah, okay. Yeah, we’ll do that”. So we went and did it. And you’ve never seen five people in a room so shit scared of something. The ten minutes before were due on stage on that June night, all just sat there looking at each other. Everyone was literally quaking, as I’m sure you could imagine, because we didn’t know whether this audience that had paid to see the Stone Roses were going to bottle us off or what. We just didn’t know. And it seems crazy now.

We played six new songs or something in that set that we were mid recording for Different Class. So bizarre. Then we finished with ‘Common People’, and you look up at the end and how every member of the audience seemed to be singing at the top of their voice, and all you could hear was the crowd singing even above your own playing. So it was pretty amazing.

Strange in a way, because you didn’t change your sound to conform to what was going on. It was actually the people who caught up with you.

Yeah, things change, don’t they? People are fickle buggers. Everybody was into plaid shirts and Nirvana a couple of years before, and then all of a sudden, everyone’s wearing daft ties and sort of corduroy a couple of years later. Fashion changes. I suppose it moved in our direction and we were the beneficiaries of such. People like different things. People like things to be new. You’ve got this lanky get arsing around on stage. People think that’s different. That’s interesting. We’ll have a bit of that.

Our lowest attended gig, which I think was two paying customers at a club called the 20th Century Club in Derby. That would have only been about five years previously, if that. Maybe even less. To play in front of about 100,000 people. It’s quite a move. And even those two people at the 20th Century Club, they’d gone in on the wrong day. A car of lads came down from Sheffield to watch, so there were more people they didn’t pay to get in of course. There were about six people in the audience, only two of which had actually paid to go in and they got in on the wrong day. And these two girls, and I hope they remember that day, because even though we could have just gone sod it, we’ll go home. We still played them a gig and hopefully they remembered it and enjoyed it. There you go. Two people.

After Different Class, you had the task of trying to follow it up. It must have been quite a period where it’s like well, where’d you go after such success.

Very much so. We had a few conversations of, like, we don’t want to churn out versions of ‘Common People’ or trying to get back to… Pulp has always really wanted to develop and try different things out. There was never sort of thing, oh, we’re going, we now going to make an album that’s dark and confusing to our fans. Maybe a bit dour. It’s kind of what comes out, really. But I know that we didn’t really want to just trot out Different Class two. It was very hard to make, This Is Hardcore. Very hard indeed. It took a long, long time. I think that maybe that’s a function of having finally found success, is that you’ve got a focus before that of where you are going when you’ve got there, where do you go next? And it’s difficult to do, basically. So it took a hell of a long time and it was tough. But the track, ‘This Is Hardcore’. That took absolutely forever to get right. But you still listen to that now and you still get goosebumps. It’s an amazing bit of work.

Further information

This interview is taken from a 2019 Strange Brew audio podcast with Nick