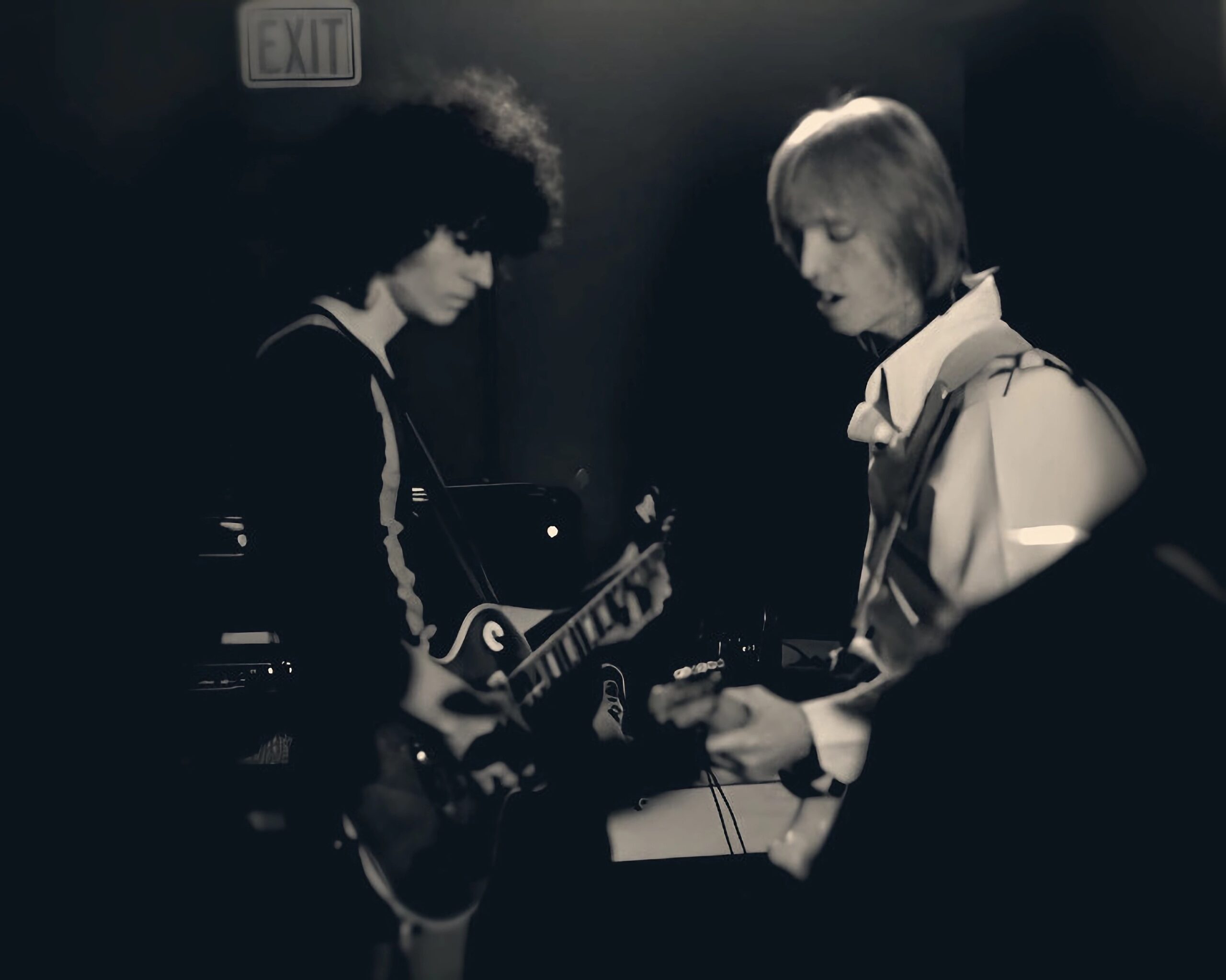

Jeff Jourard and Tom Petty, 1976 (Credit: Jeff Jourard’s archive)

Jeff Jourard has a rich history in music, having been a guitarist in the early days of Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers and a hitmaker with The Motels. He speaks with Jason Barnard about these highlights and his new role in The Hollywood Stars, as well as their new album, Starstruck.

Joining The Hollywood Stars must be an exciting new chapter for you. Considering your background, how does it feel to be a part of this band?

It’s great, kind of a full circle return for me. Glam rock was on fire in Hollywood when I first arrived in 1972 and, coincidentally, the following year Kim Fowley was putting together The Hollywood Stars. After all the different journeys I have taken into different neighborhoods of music, it is great fun to come back around to where I started. Almost like going back and visiting your old school after a million years. In 1972, it was the latest and the greatest, the brand new edgy thing – Glam, Baby! Everybody was prancing around and acting effeminate and wearing their girlfriend’s clothes, and getting — or at least acting — as wrecked and high as possible. In 2024, it isn’t that. It’s like driving a great restored old car. It’s not new anymore but it’s beautiful, runs like a demon, and it’s a classic. It means something different now. We’ve improved the suspension, put in a bigger engine, and now the radio is better.

What drew you to them now, and how do you see your addition influencing the band’s sound?

I came to The Hollywood Stars through a side door! I was looking for videos of guitar multi-effects units, also known as floor modelers. I found a good video that was just what I was looking for, and the guitar player was really good; it was obvious he knew what he was doing. I posted a question, he answered, and soon we were geeking out over equipment. It soon turned into “We should get together in person.” That’s how I met George Keller, the lead guitarist for The Hollywood Stars. Over at his place, he said I should check out the Stars to see if I liked the music. I went to a rehearsal, liked what I heard, they seemed to think I was OK, and they asked me back. Eventually, we did a photo session and I figured, “I guess I’m in the band!”

Soundwise, I could see a place for me playing straight-ahead rock rhythm with a good driven tone, like Mountain, Aerosmith, or AC/DC, and keeping it classic. I hadn’t done that in a long, long time and it was great fun going back and getting the guitar and amp sound together for that. I’m always listening to George, and to the rest of the band, and adjusting what I’m playing to have the best combined effect overall. I think that’s what I bring to sound of the band. I have a lot of experience to draw on, a lot to pick and choose from, so if I hear something that reminds me of something I heard a long time ago, I know how to flesh it out. Sometimes I’ll play just one note, or even nothing when that’s the right thing to do.

What can we expect from Starstruck?

You can expect some references to the glam rock years, some classic rock, some hard rock, a power ballad, and there’s even one that’s almost like 1960s R&B soul. It’s a natural progression from what came before. Most of the songs stay true to the general style laid out in the ‘70s, but the new band and this new album rocks harder than the previous material. It still has the melodic qualities of the original band, but we do live in this world, not the world of 1973. We play what feels right for now, the same approach they used back then. It’s a strong album, the songs are great, and we played well in the studio. We rehearsed a lot to prep for the sessions and played just about all the songs as a live band in the studio to get the foundation tracks. Then just a few overdubs to pretty them up. Not too many bands record that way anymore, it’s the old-school way. The bonus is that we sound like the record when we play live because that’s how it was made.

Can you share more about how your childhood experiences and exposure to various musical influences shaped your journey as a musician?

I was born in Buffalo, New York, but my family moved multiple times before settling in Gainesville, Florida when I was six years old. Both my parents were very into music, so there was always music around either on the radio, record player, or live in the house. My dad liked folk music and would play his nylon string guitar and sing. Later, he got into classical guitar and even flamenco. There was a group of three or four of these guys and they would sit in a circle and play from sheet music.

When I was nine, I picked up his guitar and liked the sound — that’s when I got started. My mom was very artsy, she was into photography, theater, painting, modern dance, very much a bohemian. She especially liked folk blues and that’s how I got exposed to blues guitar. Every year, there was a big folk music festival in White Springs, right by the Suwannee River. Some of those folks would come by our house after the event to drink a play a bit. I watched what they were doing and tried to copy it. When one of those guys played some blues with the bendy notes, it went right through to me — I wanted to make that sound.

A few years later, our whole family went to London and stayed there a little over a year. It just so happened that we arrived in the middle of the red-hot Swinging Sixties. The youth culture was exploding, all the arts were entwined, saying the same thing — youth, energy, newness, style, fashion. The miniskirt was shocking the old folks, Mods on scooters, Rockers in leather and on bikes, the new bands were The Who, The Kinks, The Animals, Manfred Mann. I was still too young to go out to see them on weekends but there were many TV shows that hosted the new bands. There was another family from Gainesville in England at the same time; we knew them from home. They had a son just about my age and he was as knocked out by all this musical excitement as I was. We made a solemn oath that we would start a band as soon as we got home, and that’s what we did.

We got plenty of gigs in the local taverns and fraternity row at the University, covering all those songs we heard the English bands doing. Many of them were American songs, some blues, some R&B, some pop, we did all of it. It was a great education. Like so many kids my age, the Stones introduced me to artists from my own country, like Howling Wolf, Jimmy Reed, Muddy Waters. My mom kept bringing home albums for me that had pictures of guitars on the cover. she didn’t really know what was on the records, but the first three were Howling Wolf, Muddy Waters, and Jimmy Reed! And Duane Eddy, too, which I really liked.

Could you tell us more about the music scene in Gainesville during that time and how it influenced your musical development?

Gainesville is a college town. The University of Florida is there, home of The Gators! It had the feel of a small Southern town — home to ranchers, workingmen, turpentine and creosote and varnish — along with all the traditional Southern culture and values that really didn’t mix well with the more educated and liberal students and faculty who were usually from out of town. On the one hand, you had native music that was country, blues music, and old-time folk music like bluegrass, while on the other hand, you had a young population into The Yardbirds, the Stones, The Kinks, The Mothers, and all that.

When I was very young, Gainesville had mostly country musicians, with folkies from the University, and a few jazz guys taking the lounge gigs. Over time, rock came in and then lots of “show” bands that were young, wore matching outfits, and played the pop hits of the day. We also had a strong current of R&B music that was very popular in the bars and fraternities. At the time, R&B meant Ray Charles, Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, Barbara Lynn, Rufus Thomas, and many more. Most nights, with a little effort I could get WLAC to come in on the radio, all the way from Nashville. The nighttime programs were all R&B, soul, and blues. I know thousands of musicians tell the same story of listening to WLAC at night and getting an education.

The series of bar bands I played in focused mostly on the songs that the English bands covered. We played them as much like The Animals, the Stones and The Yardbirds as we could. But by popular demand, we also had to play the R&B songs so that people could dance the boogaloo. They absolutely loved tunes like “Knock on Wood,” “Give Me a Little Sign,” and “Mustang Sally.” All this stuff from A to Z got into my blood, as it did for everybody else who played in town. It became the undocumented Gainesville groove. I think that was true in a lot of the South — look at the white studio musicians in Muscle Shoals that played on so many soulful, funky black records, and nobody knew they were white. Gainesville had some of that same feeling and it soaked into all of us who grew up and lived there.

Do you have any standout memories or experiences from your time performing with your early groups?

As a young guy, in my early bar band days, watching the incredibly pretty, drunk Gator girls dancing in shorts and tank tops to our playing was unforgettable. University of Florida girls were so pretty that it made me wonder what was wrong when I’d visit other places and the girls looked normal.

There was this thing — as a band you wanted to catch fire and just get totally lost in the music, and have it take off on its own. Everybody in the room could feel it and people would just go nuts, jumping up and down and hollering. Some of the guys would even dance “The Gator.” When there was no place left to let the excitement out, guys would drop to the floor in a sort of push-up position, and then jack their legs around, doing some kind of simulated sex thing, and a circle would form around them cheering and yelling. I think that was a very local thing to Gainesville, but Don Henley mentioned it in one of his songs. Don is not from Gainesville, but he worked a lot with original Heartbreakers drummer Stan Lynch, so that’s probably where he got it.

One time, I was playing in a psychedelic band and we were offered an upright piano to destroy during our show. I got to do the honors. It was during spring break and several fraternities got together and rented a hall. The hall was decked out like the Fillmore West, with strobe lights, balloons, and incense. They also very kindly provided a sledgehammer. The band thought it would be funny for me to do it because I was the youngest and weighed about 120 pounds. So, with all the strobes going, and the liquid lights and the blacklights, I smashed the piano to splinters. I wore myself out completely and two roadies carried me off in a stretcher, which they had planned in advance. Then, when we were packed up and leaving, cop cars came screeching from all directions, boxed us in, and pulled us back into the parking lot. They planted a joint on us, “found” it, and then hauled us all off to jail. It took six months to go through all the hearings, papers, and verdicts before the case was thrown out.

Can you tell me about your group RGF, meeting Tom Petty and the rivalry between Mudcrutch and RGF?

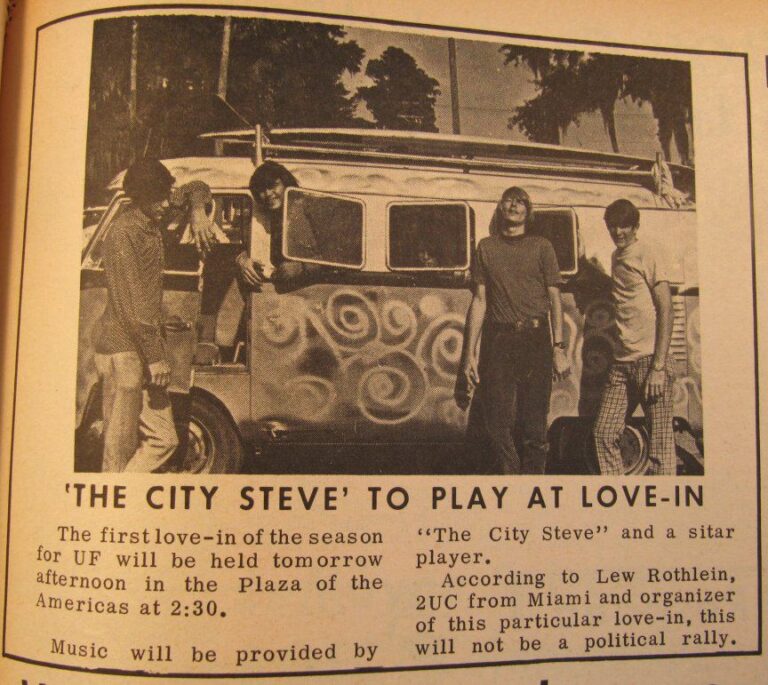

RGF was the outgrowth of four or five bands that came before, with members leaving, new guys joining, and a new style and name happening each time. Around 1969, we started a band with some cool new guys and were very much embedded in the local hippie community. We all lived in a house right among all the other hippies — where rent was cheap! To outsiders, we looked rough, dirty, and scary, but we were all just goofy stoned hippies. We hadn’t picked a name yet but we got a Saturday gig playing for free on the lawn behind the University library. Somebody had set up a makeshift stage out of folding tables but there was no power.

While one of us was standing on top of our van, tapping into a light pole nearby, a very traditional College Joe came driving up onto the lawn in a little sports car with the top down. He reeked of privilege and squareness. His girlfriend was sitting in the passenger seat. Showing off, the guy said, “Hey, you guys playing today? What’s the name of the band?” A friend of ours who was always quick to be rude told him “The Fuck.” It’s hard to explain how forbidden that word was back then — it was way beyond foul to the average person. Then our drummer chimed in with “No, it’s actually ‘The Good Fuck’.” The girl started pleading with him, “Let’s go!,” but we all piled on with more versions of the name. “No, it’s the Really Good Fuck. Wait, it’s actually The Really Really Good Fucking Fuckers.” The girl wanted out of there immediately and her boyfriend sped off. We had a big laugh about it and somebody said, “Why not?” So, we shortened it to Real Good Fuck and used RGF. We became the biggest band in town.

Tom Petty was a local face, so was Don Felder, and so were 30 more that never made a name for themselves outside Florida. We always saw each other at the music store in town — it was as much a hangout as it was a place to buy stuff. There weren’t many safe places for guys with long hair. I knew Petty from around town. He had droopy long hair, talked slow, and didn’t seem like he would ever do anything special. He was fronting Mudcrutch, a country rock band that didn’t make much sense to me. I was into Led Zeppelin, Traffic, Cream, Steppenwolf, the MC5. Country rock seemed to be a dead end.

There was no actual rivalry. Baird Duncan, a local wild child, decided to be a manager and approached RGF and Mudcrutch to manage and book gigs for us. The main draw was that his family had a guesthouse that could be used as a free rehearsal space. Usually, RGF and Mudcrutch would rehearse after each other on the same day, which meant waiting outside for the other band to finish and pack up. At our rehearsals, we would make fun of what we had heard, and we’d play goofy hillbilly versions of Mudcrutch tunes. Years later, in Los Angeles, when I was rehearsing with Petty and the early Heartbreakers, I mentioned that to Mike Campbell. He said, “Yeah, I know, we heard y’all doing that. We made fun of y’all, too.” That’s as close to any rivalry we ever got!

Can you walk us through the circumstances surrounding your involvement in the recording process of Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers debut album?

Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers was the result of a long period of development. Denny Cordell co-owned Shelter records with Leon Russell, and they recorded sessions for Mudcrutch, who had moved to Los Angeles not long after I arrived in 1972. After the second Mudcrutch single, “Depot Street,” failed to chart in 1975, the band broke up. By that point, Tom was fed up with bands and wanted to go solo. Cordell kept Petty under contract. He booked a lot of recording sessions for Tom using top L.A. session musicians. At the same time, all the former Mudcrutch members went off in different directions, including Benmont Tench who booked studio time to record some demos.

Benmont called in musicians he knew, which was basically all the guys from Gainesville, including Stan Lynch. I knew Stan because he was friends with my brother and I was living with his sister. Stan called me on the second night and said, “You should come down here, we’re having a blast! Bring your guitar.” So, I joined in, and it was easy to fall back into the Gainesville groove. We all knew each other, and without really knowing it, there was a Gainesville way of playing that was just there. Either Petty came by to visit Benmont, or Benmont played the tracks to him — either way, Petty liked what we were doing. He wasn’t getting what he needed from the professional L.A. session guys. They were accurate and steady and learned very quickly, but somehow that familiar feeling was missing. So, Tom started using us on sessions, one at a time, and eventually replaced all the pros with the hometown boys.

At that point, we were rehearsing in the spare space at Shelter Records, and most of us felt like we had the makings of a band. Tom was not interested in dealing with band drama anymore, but Denny believed that the public likes a star in a band more than a star alone. So, as long as Tom was the top boss and didn’t have to get into any arguments, he was OK with the idea.

Shelter’s Denny Cordell/Leon Russell partnership had fallen apart. All the assets were frozen while they worked things out which meant there was no money for sessions or musicians. But there was a recording studio in Leon’s hometown of Tulsa. I don’t know how it came to pass, but all the recording equipment from that studio got trucked to Hollywood and installed in the big spare space where we rehearsed. That became the recording studio for most of the debut album. It was a very basic setup with a make-shift control room, cables all over the place. They never got the buzz out of the headphone system, but the machines were top-notch. People would drop by all the time, especially Dwight Twilley and Phil Seymour who did several background vocals on the album, such as “American Girl.” That song was tracked on July 4, 1976. The studio didn’t have air conditioning and we were all just soaked in sweat that weekend. I remember that I was put off by the heat, and I didn’t particularly like that song. Good thing nobody asked for my opinion — it was a huge hit.

Despite your contributions to the album, you didn’t do many shows with Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers. What led to this limited live performance schedule, and how did you navigate that period professionally?

The Heartbreakers played exactly one gig before going to England. It happened at a teen recreation center in the San Fernando Valley. I was with them that night, and I have a cassette of the show. The real story is that even though I was totally into the band, and felt that it was natural for all of us Gainesville players to get together, I also was struggling to find a place for myself in the music. The songs were completely stripped-down, and Mike and I were trying to come up with only the most essential guitar parts. Mike had worked with Tom for years and was better at this process than me. I contributed some more decorative parts, which quickly got vetoed, and that was frustrating. Tom probably saw trouble brewing on the horizon, and to the surprise of everybody in the band, he cut me loose right before “we” were all scheduled to go to England. Like the rest of the guys, I was picking out my suitcase and buying vitamins for the trip, so it was a bolt out of the blue. The artwork for the album was redone to eliminate my photo. They took off to England and that was the end of my ride. I took it hard — the Heartbreakers’ camp was pretty much everybody I knew, and might have started another band with.

The point of sending the band to England was to generate press and good reviews. Cordell was English and he knew how it worked. The album was not getting any traction in the U.S. It was initially considered out of date, behind the times, old hat. In England, the band would be seen as an exotic American import worth checking out. And that’s exactly how it panned out. The English music press gushed over the Heartbreakers, and before the inevitable backlash could start — and it always does with the English press — they came back to America with a mountain of glowing reviews which sparked the interest of the music industry here.

It’s amusing to learn that your jacket ended up on the cover of the debut album. How did that unexpected turn of events come about, and what was your reaction when you saw Tom Petty wearing it for the photoshoot?

My reaction was, “I brought that for me!” We were told to bring a lot of clothes for a session at the home of photographer Ed Caraeff, where he had a studio. We did group shots wearing a couple of changes of outfits and then we did solo shots. The stylist suggested that Tom try my jacket along with the ammo belt that Stan Lynch brought. I suspect that Tom thought he looked ridiculous and that accounts for the crooked smirk that ended up on the album cover. Tom was a lifetime Elvis fan, and Bob Marley fan, I doubt he could see the point of that outfit! He certainly never revisited that look again.

Your determination to join The Motels is quite remarkable. What motivated you to pursue joining the band?

In the space of 18 months, my dad died, my girlfriend left me, and I got booted from the Heartbreakers. I could go back to Gainesville feeling beaten and depressed, or I could take another crack at being in a successful band. One principle that has served me well throughout the years is my “Zag Theory.” If one way of working (“The Zig”) isn’t doing the trick, what would its opposite (“The Zag”) be? I decided to conduct my life like a combat operation, with absolute logic and determination, executing my plans regardless of how I felt. To make a long story short, it worked, and I eventually located Martha Davis. The original Motels had broken up and I told her we were starting a new band together.

But I paid a price for my “Zag Theory.” Turning myself into The Terminator really did me more harm than good. It made me into a cold, methodical asshole. Still, the Motels would not have happened if I hadn’t been in that head space during that time. I’m glad to not be that guy anymore, even though he made things happen. I abandoned that approach because it’s upside down and backwards. The better approach is to put the soul in first position and use the Terminator to serve the soul. Instead of trying to force the world to bend to my will, I’m now having a better life just finding the flow and seeing what comes my way.

Collaborating with your brother in The Motels must have added an extra layer of connection to the band dynamic. How did your sibling relationship influence your musical collaboration, and what was it like working together creatively?

It was great. We know the same music and he understands my references. I was able to really lean hard on Marty, drilling parts, coaxing him to do difficult things, to the point that anybody else would probably have quit. But he trusted my instincts. I used to tape our rehearsals from beginning to end, then, late into the night I would go over them at home, looking for moments where something unique happened. The band would often be doodling around before rehearsal even started, or between songs — maybe scrolling through different settings, or adjusting something without thinking about what they were playing. Marty especially would do this.

There would be these moments where a fantastic combination of accidental sounds would happen. The next time we got together, I would show it to Marty and try to get him to repeat it — which was hard because it might be odd notes in an odd timing — but to his eternal credit, he drilled down until he got it. Another thing we did was slip in bits of TV themes. I pulled in some bits from the “Twilight Zone” theme while Marty would sneak in something from “Bewitched.” Having these little inside jokes really made it fun. I don’t think they ever were spotted, either.

Beyond The Motels, you’ve had various collaborations since the 80s. Could you share more about your experiences working with different artists and bands during that time?

Jason, there really hasn’t been that much. I lost my taste for the business side of the music industry and just played locally with interesting situations that came my way. One was to record part of an album with Peter Noone’s The Tremblers, another was a band called Leroy and The Lifters that played in the middle of Flipper’s Roller Boogie Lounge, which was a members-only debauched roller rink. I appeared in disguise with L.A. punks Geza X & the Mommymen, and did a stint with Phast Phreddie and Thee Precisions, which was a strange case of Hollywood rockers playing bepop, swing and R&B. Then, there was a short stint with Melvis and the Megatones. For several years, I played with The Roosters, a band which played all the songs I first heard during that first formative year in England. As far as what any of this did for my musical growth, that’s up for debate, but it’s been an eclectic spectrum of styles.

To close, what’s next for you and The Hollywood Stars?

Next up is a gig at the legendary Viper Room on June 15 to celebrate the release of the new Starstruckalbum. Depending on when your story runs, we may have already done it. There’s a publicist working with us to spread the word (“Hi, Randy Haecker!”) and we’ll see what that brings to our door. Spain and England seem to be digging what we’re doing, so we may be touring those countries soon. I’d like to shout out to all the Hollywood Stars — Scott Phares, Terry Rae, Michael Rummans, and George Keller, who got me into this! …Who doesn’t love to see their name in print? Cheers, everybody!

I had a Dodge van in Gville. I’d schlep the Marshall stacks and acoustic 360s to the RGF gigs. They had a yellow school bus and took off to Boston to get to an Earthday gig. So I drove from Gville to Boston and parked and started walking down Mass Ave, and a minute or two later here comes the whole RGF band in their VW van with their faces smashed up against the windows yelling Look Its Gardner! F’in Gardner! Cool coincidence. Somewhat Karmic too.

Jeff also had some pet projects, The Flames, a band called Naked that morphed into O the Band with his then wife Gina Jourard, Joe Romersa, Trevor Zimmerman and Chick Singer.

https://youtu.be/OGzNXk-qoPk?si=VlSRHxwfEwTaSdZH

https://youtu.be/7jHcn3JgvUA?si=05bhBhqIUMjdWEAi