By Jason Barnard

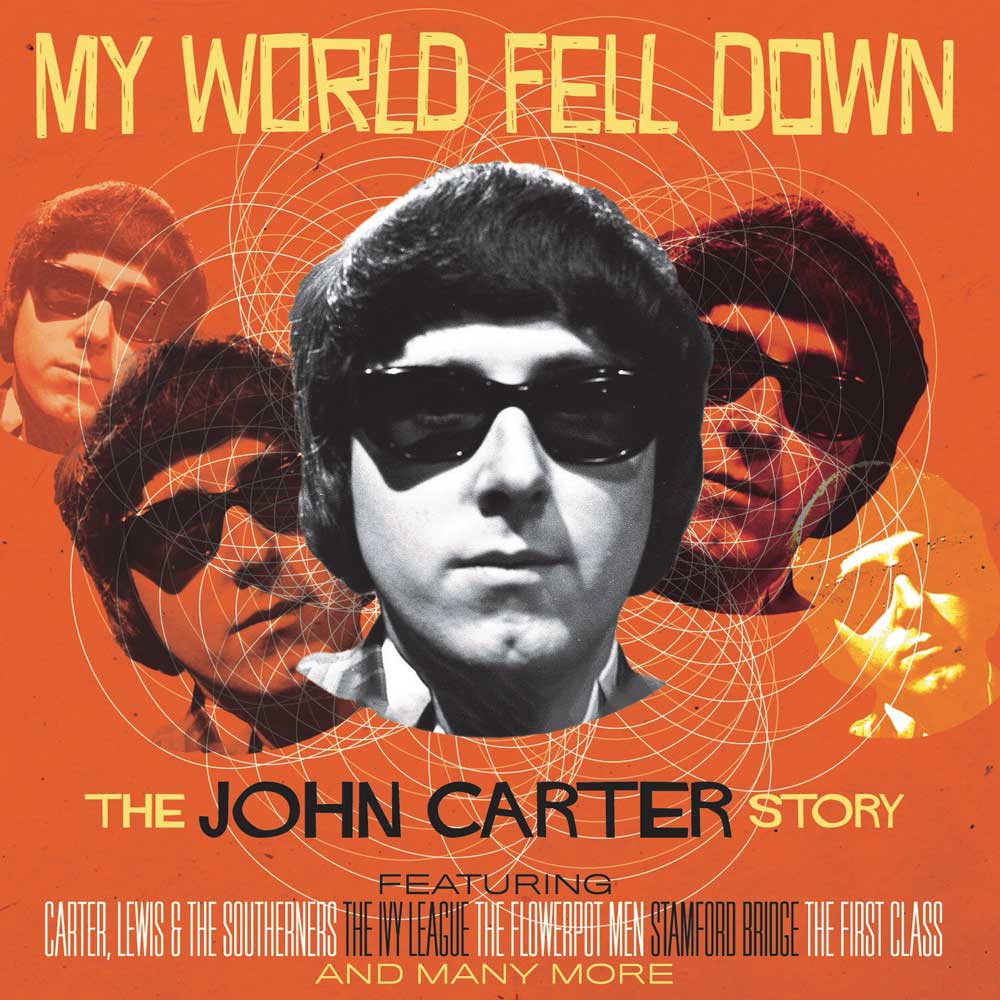

John Carter, one of British 60s pop’s most enduring backroom figures, talks about his life in music including Carter-Lewis and the Southerners, The Ivy League, The Flower Pot Men, Kincade and The First Class.

Hello, John, maybe it’s good to start at the beginning. Is it right that you and Ken Lewis got into the industry by knocking on doors on Denmark Street.

John: Absolutely. I remember it well. We just went round Denmark Street a few times, knocking on doors until someone said “Well, come in, we’ll discuss it. And we were lucky one time and then that was it. We were in.

And you knew Ken from school, is that right?

John: Yeah, we were at school together in Birmingham.

So was the idea to form a group around you both, which is why Carter Lewis and the Southerners came about?

John: Well, we got to know people. We were doing some sessions for people, and we’d meet other people that we thought, oh, I know you from so and so and we become friends. It all worked like that.

And even in those early days, the songs were so strong, such as “Sweet and Tender Romance”, for example. How did you write songs with Ken?

John: Well, it’s very difficult to explain, but we just got together. I played guitar, Ken played piano, and we just said to each other, “What do you think of this? And then I said, “That’s great. What do you think of this?” We worked out the best one that we thought would develop into a good song and worked on that.

On this set as well there are demo versions of songs that are really well recorded, like “Can’t You Hear My Heartbeat” which was a hit for Herman’s Hermits. So you seem to put a lot of effort into those demos.

John: We did. I always thought if you do a good demo, people are going to take more notice of it when they think, “Shall we record this with our artists?” So we tried to make our demos as good as possible.

What led to Carter Lewis and the Southerners morphing into the Ivy League. Was it working with Perry Ford?

John: The Ivy League was working with Perry for a while. We wanted a group of three people, so we needed one more, there was me and Ken, and we had to get another in one for good harmonies. Perry was around Denmark Street all the time, like we were. And we bumped into him and said, “You fancy coming and joining us?” And he did.

All three of you were on a lot of other artists’ material, and that included The Who’s “I Can’t Explain”. I understand that in terms of getting involved with that, you actually didn’t know what session you were going to be on.

John: That’s right. You just got a phone call. We were asked to go and do a session. We didn’t know who it was going to be with. You just turn up. And in fact, most of the time they don’t give you any music to look at. You just make it up as you go. So you listen to the song that they’re trying to do and make up your own harmonies.

What many people won’t know is that you were on tracks by Tom Jones, Jeff Beck and even Chris Farlowe.

John: All of these, yes. With people that do backing vocals, they don’t get a mention, really. It’s not important to people. They just want to hear the final record. And if they think “Oh, this is great” they buy it. But they don’t say, “I wonder who is on the backing vocals.”

It was such a prolific period doing demos, backing vocals and other artists. You must have been working non stop.

John: I would have thought it wasn’t that bad. But yeah, you’re right. We were working every day doing something like that, and it did get a bit over the top.

The Ivy League as well were hugely successful. The vocals and harmonies on “Tossing and Turning” are still unmistakable. So The Ivy League was about adding the harmony sound.

John: Yeah, we tried to make that as good as possible because we loved that song.

Were The Beach Boys and influence in that period?

John: I would say they were. I used to love The Beach Boys, and it’s obvious, if I’m listening to something like that, it’s going to influence me in a way. Definitely.

We talked about you singing on other songwriters songs, and famously, you also sung the lead vocals on Winchester Cathedral as well.

John: That’s right. Would you like a try? [John sings Winchester Cathedral in a 20s voice and laughs]

That was when Ken decided to stay on in The Ivy League. But you linked up with Geoff Stephens.

John: That’s right, yeah, absolutely. Geoff asked me to do the demo of that, which turned out into more than a demo, and I really enjoyed doing it.

I’ve read that Geoff couldn’t afford a session payment, so he gave you a royalty on that track.

John: Is that right? Yes, Geoff never had any money.

Well, it was a hit everywhere and it even topped the charts in America. So you must have been very grateful for taking that royalty.

John: Absolutely. That was one of the best things I’ve done I think, for money anyway. No, I enjoyed doing it.

You continued working with Geoff and going more into the studio. I’ve read that you just weren’t a fan of the touring at the time that you were more at home in the studio, is that right?

John: I got fed up with touring very much. I mean, I didn’t like touring at all. I’d like to be at home with my wife and having fun around where we lived and going out to concerts and writing songs and all that. And I started writing songs with my wife. So it all worked out really well.

“My World Fell Down” is a real highlight of that period of working with Geoff with the songwriting. But in America, the record producer, Gary Usher, took that song and added more production. And that’s a song that is really revered now.

John: I agree. I’m really glad we wrote that. And as you say, the American version is brilliant I thought.

Yeah. Because I think it was Bruce Johnston of the Beach Boys, as well as Glen Campbell, who even played on Sagittarius’s version.

John: That’s right. Yeah. So we were lucky with that one.

Well, I think the songwriting was the foundation. Your version was fantastic. And they just added to it.

John: Yeah, they did. Absolutely right.

And so when Ken left the Ivy League, you started working with him again. That ended up leading to The Flower Pot Men and the “Let’s Go to San Francisco” song, which was a huge hit.

John: Yes.

It was a very lush and orchestral sound. So you must have been inspired by the American scene.

John: That’s right. Yeah. We took notice of what was going on in America, and it was an influence. I don’t think you can sort of say we took no notice of it. We just listened to it. We didn’t copy anything. It was just, as I say, an influence. Flowerpower.

And the name of the group was from Watch With Mother, wasn’t it? The children’s show.

John: Bill and Ben, yes.

In a similar pattern you didn’t want to front the group. You prefered other people to perform live so you could focus in the studio.

John: Yeah. That was always what I liked doing. I’d like to be in the studio recording new things, but going on the road. I did a little bit of it, didn’t I? But not very much.

You were working with great musicians in that time, like John Ford and Richard Hudson. So you must have had some great musicians playing with you in the studio on that material.

John: I agree we did. There were some wonderful players around in those days. I got to mention Clem.

Clem Cattini, an incredible drummer.

John: He was wonderful.

“Dreams Are Ten a Penny” was released under the Kincade name showing the work with your wife, Gill, deepened.

John: [To Gill] We loved writing together, didn’t we?

Gill: Oh, yes. It was good that we were both in the same place being able to bounce ideas off each other. So I was around if John had an idea he’d play it to me and see if I wanted to work on it, and I’d go away and have a think and come up with some ideas.

John: It all worked very well.

And did either of you particularly focus on one side of the songs, like the melody or the lyrics, or was it combined?

Gill: Oh, no, I’m just the lyric writer. John is the musician and he also had ideas about the lyrics. And he would also give me a heads up as to what, how lyrics should go in order to sing right. But I maybe have an idea for a chorus or a hook or a title, and then we talk about it and see if it worked and kick it around until it did.

John: It was usually brilliant. She’s great.

Gill: I was handy and cheap! [Both laugh]

And that continued with “Beach Baby” as well, which came under The First Class name. It was almost like a British version of the Beach Boys sound.

John: It was, yeah.

Was it consciously written for that style?

John: I don’t think it was. It was just that kind of song, you know, more about that song.That song kind of needed…

Gill: Big orchestral…

John: Yeah.

And on Beach Baby, it’s Tony Burrows who did the lead vocals. So you’ve got a strong association with Tony, who sang quite a lot of your material.

John: Oh, yeah. He’s been a friend for years and years.

Gill: You’ve done a session with sessions with him all from way back.So you’ve known him a long time.

John: I know him very well.

The amazing thing about Beach Baby is that that song was a huge hit in America, which is like selling sand to Arabia or something. Amazing that you were actually emulating their sound. It must have been quite gratifying.

John: Really surprising as well.

By the mid 70s, there was a lot of work on advertising jingles. That was the period where songs for adverts were essential.

John: Yeah, it was a good time. I enjoyed doing that. And as you say, it was really well paid.

Gill: It was quite frantic though wasn’t it, something written in the morning for a session the next day.

There are songs that came out of it. There was a song called the “Sound of Summer” that was originally written for Butlins but actually became a hit across the world.

John: That’s right. Yeah.

Gill: It was recorded by a Hungarian group and it was a big hit in Japan by the same group. So it’s international.

And also in that period, you were writing material for films as well.

Gill: I think that was mostly companies using songs that had already been recorded. Just asked to use a particular song rather than specifically.

John: I think occasionally we did get asked to write something for a certain film.

In the last decade you’ve been writing in the duo Hamzter. There’s some really great material like “Your Reply Made Me Cry” which combines a bit of latin styles but also some of the core melody that you’ve always had. John, that must be great to have new material coming out.

John: Absolutely. Thanks to Salomao, who’s here now who joins us in that?

Salomao: Thanks, John.

John: He’s making it a bit different so we appreciate all that.

You’ve got a range of videos that have come out that accompany the songs but obviously people can get the music directly and stream it and there’ve been at least three albums, I think, as Hamzter.

Salomao: Three albums, two on the way.

John: Two on the way [Everyone laughs]

So lots to look forward to. Thank you so much for your time. It’s much appreciated. Thank you.

John: It was a pleasure to talk to you.

Gill: Thanks very much.

Salomao: Thanks Jason