Rick Buckler reflects on The Jam’s final year, 1982, with Jason Barnard. Rick covers the recording and release of final studio album, The Gift, their last shows and the announcement of, and his view today of Paul Weller and the split.

I’ve got this wonderful book in front of me. It’s quite moving in a way, you’ve got an introduction where you talk about the start of the band and the first single ‘In The City’. As you go through it, there’s the build up to 1982. And then the year comes to pass, it really is a remarkable window in time for The Jam.

To be honest, it wasn’t an easy book to write. When I wrote my autobiography, I just focused on the really good stuff that happened with the band, and probably what most people remember about the band from an external point of view. So tackling this issue of 1982 and why the band split up was quite difficult, because I had to cast my mind back to what exactly was happening in that year. And it was a bit emotional, because I had to remind myself of the really strange situation that we found ourselves in. Now, the optimism that we started the year with, we’d got to a point where we just obviously established ourselves in more than just Britain as an act etc. And we didn’t really have to struggle quite so much to prove ourselves. We still pushed ourselves, don’t get me wrong, we didn’t really want to stand still. All our albums were very different, because of that attitude of wanting to do something different, and do something which moved the band forward, we still had that drive within us. And then to suddenly find that Paul decided that that was it, when we knew that there was lots more in us, both myself and Bruce. And I think anybody who looked at the progress of the band knew that there was so much more, we hadn’t really reached I don’t think, any sort of end game. We were still selling records, we were still doing really well, in the concerts, they were still selling tickets, there was still a lot of interest in the band. We were still giving our everything to it. So yeah, when you asked the question, what on earth could go wrong now? Do you know what I mean? [laughs] It was a very strange scenario in that year to think back on and to try and write about it in a way. Not looking back, a lot of people who contributed to the book simply looked back on it. I don’t think they really put themselves in the place that they were at the time. And there’s a lot of retrospective thinking, which is easy to do, hindsight and everything. But, fair enough, that’s just the way it is. But from my point of view, I really wanted to get it across about how we felt at the time and the shock, I suppose in a way that this was happening. And it was, it was quite a shock, I think for everybody concerned.

Absolutely. And just prior, 1980 to 81, you’ve got the band at the peak. Tracks like ‘Funeral Pyre’, your drumming on that track alone is phenomenal. As you’re reading the book, you’ve got kind of what’s going on in politics, the really harsh winter in 1981. And then you go into the studio and start recording ‘The Gift. So you’ve got those photos and the context. You start to get that atmosphere and the anticipation as we’re about to enter the year.

Yes, it is a really difficult one to… I remember one thing that struck me immediately, when I put myself back into 1982 was how we just got on with it. Do you know what I mean? We spoke about Paul leaving, and then we just got back into what we were doing, we immersed ourselves in the recording, we were in a recording studio, where Paul made the announcement. We got straight back into work. And it was almost not mentioned again, the reasons why Paul wanted to leave. That was the thing, I think people still scratch their heads over today is the reason, the reason. There was no reason. There was no great scheme. The reason that Paul gave us was about why he wanted to leave the band in that initial meeting was rubbish, basically. He said that he really felt like he was on a treadmill, and that he wanted to get off. But this was a treadmill that we wanted to get on. We always wanted to get on, we fought so hard to get on it. So to find somebody in the band saying, “Well, I want to get off now.” You think “Well, that’s crazy. That’s mad.” And of course the first thing you went and did was when and got onto a very similar treadmill. He re-signed with Polydor Records before the band had split and just carried on on the same treadmill. So that didn’t make any sense from the get go. And then when we heard in 1983, in the year after we split, that Paul had given it this sort of fairy story of, “Oh, I wanted the band to mean something.” I just thought to myself, it just struck me that there was something wrong here, that this was not a valid reason. I think I know what the reason was, I think a lot of it had to do with how the band was managed, because there was a lot of questions being asked about, “Why is it that, John [Weller – The Jam’s manager], and Paul had all this money, and me and Bruce didn’t have very much at all.

There was this first and second class citizen thing happening within our own band. We were beginning to ask questions, why am I driving around in this, this wreck of a car, and I can’t get out of Top of the Pops without the car breaking down. And it was just things like that. And also, on the other side of it, how we very gentlemanly accepted the fact that if Paul wanted to leave, we could deal with that, there was not a problem with that. So if that’s what he wanted to do, he was perfectly entitled to call it a day and to walk away from it. What I think annoyed me especially, was the rubbish that was talked about, he did it for some grand design. I’m sorry, but that’s just not holding any water with me at all. The more I think about it, and the more people ask me over the years, and I’m sure they’ve asked the same thing of Bruce, “Why did this happen?” There weren’t any musical differences. It wasn’t wanting to move on if there was because The Jam had stepped up to the mark and evolved in every possible way, musically, and songwriting and we tried lots of different things. We brought in brass sections. We were probably one of the most flexible bands in the world at the time, to be able to move to different areas and styles. As a band that’s working with itself, myself and Bruce as a rhythm section, we contributed a lot to the sound of the band.

That was a stark realisation when you listen to Style Council stuff. How bland it sounds to me, anyway. So I don’t think there’s any real bitterness why, if Paul wants to leave, fine. That’s absolutely fine. We can live with that. What annoys me, like I say, really, more than anything else, was the rubbish that was talked about, as if there was something to be covered up about why he was leaving. And I think a lot of it was to do with the way that the band was managed, the way that it was, sooner or later was going to mean not to be too blunt. But I think the shit would have hit the fan sooner or later. And I don’t think he really wanted to be in that scenario. So I think he pulled the plug first. That’s the only logical explanation. If you think of all the other arguments that don’t seem to hold water, that one seems to be the most logical reason really. Fine. It’s just because there was a lot that happened afterwards why we had to take the Wellers to court. The difficulty we had getting our royalties. And it was almost like somebody whispered in Paul’s ear, “You’re the band, you’re the only one that’s worth anything here, which was I don’t know, there’s a lot you can speculate, this is the problem. There’s been so much speculation about the reasons why all these things came about. Another thing that came to my mind was, we used to look back on bands in the 60s and think, look at all these mistakes these bands made, management’s run off with all the money, ah ha, that wouldn’t happen to us, you know what I mean? There’s certainly a good story to be told for people who are forming bands now, that a good piece of advice is to learn the business, to know what you’re entitled to. And to know about the royalties and the different sorts of royalties that come in from a band and to know the business. A lot of people learn their instrument and stagecraft. But to actually learn the music industry, and the business and the way it’s run, is, I think, just as important for somebody’s career to know how to. It’s almost like business school, I suppose, in a way. So maybe there’s a tale to be told there that people coming into the industry should learn a lot about the industry as well as learning their own instrument.

When you look at 1982 you were the biggest band in Britain. ‘A Town Called Malice ‘ arguably the biggest Jam single, you’ve got your drums, Bruce’s bass propelling that track. You really were at that peak and when you compare that song alone to the very start of your career, the sound has continued to evolve. So you were at your commercial and creative peak.

Yes, we were very proud of the fact that not one album is the same as any other album. I think we markedly moved on from In The City to Modern World especially, that became a bit of a shock to the record company, because they just wanted the first album repeated, they wanted another version of that, because that sold well. So they thought, “Do the same thing again, that’ll be good”. And we weren’t really going to do that. We felt that there were other things that we wanted to do. And you do get a lot of bands that do that they sort of get themselves, it’s like a trench, you know this works, I’m gonna stay here. And you don’t go out of your comfort zone. And that’s fine, if that’s what you want to do. But I think bands should come out of their comfort zone, they should explore their extremes. We didn’t get it right all the time. There were some songs that we did that were a little bit questionable, really. But we always had the core of what The Jam was about, to fall back on and to come into, to return to home base if you like, and then start to look out and explore different ways. Bringing in brass players, steel bands and backing vocals and trying to expand what was… The Jam was a four piece band but with only three members. The reason that I think we looked at it like that, it’s because we always wanted to be a four piece band, but we could never get a fourth member. So we tried very hard to sound like a four piece band. When we were on stage, there’s no way to hide with a three piece. If anybody stops for any reason, you know about it. And we took advantage of that. And I think musically that shows. I quite admire three piece bands, because I know how difficult it is to make it sound full and interesting. You get a five piece band, you get lazy keyboard players. You get some people who just drop out “I won’t do a guitar solo now”. But I think in a three piece, you really have to pull your weight. So there’s a certain discipline about three pieces. So I think that reflects in us driving ourselves to explore different musical parts of it.

And even with ‘Malice’, which was a double A-side. The fact that you were on Top of the Pops and did ‘Precious’ and ‘Malice’ in one show, that mustn’t have been done many times.

Maybe the Beatles did it. I’m not absolutely sure. But yeah, it was a real honour for them to say that to us because they don’t normally let you do that. And if you release the double A side, they never liked it. They said, “Well, you’ve got to pick one of the songs to shine the light on”. But they let us do that. And it’s an amazing thing. And obviously “A Town Called Malice” was the main song there. But because of the success the band had, even the BBC recognised that, to actually let us do that was just fabulous.

As well as “A Town Called Malice”, another song from that era that was a big single was “Just Who Is The Five O’Clock Hero”. Both of those songs take an element of working class life, Paul’s lyrics, and that resonated for the whole band given your background, and also the fans background.

Yes, Paul’s lyrics were absolutely fantastic. That’s why people will still relate to it, and in some ways still relate to it to this day, because it still resonates with people. There’s something in there. Paul was a great observer of life going on around, it wasn’t preaching anything in particular, it was just observing and saying, well, this is me, this is what I see, from my position. Songs like ‘Man In A Corner Shop” and what have you, they’re just fabulous little stories and scenarios. They’re so well displayed in the lyrics. It was great to have something like that to try and palette musically to find something musically that supported that lyric. No doubt that Paul was at his peak in that time, anyway, with his songwriting and with the lyrics. This comes into the realm of, when people talk about the band getting back together again. Because there was a momentum that was built up over the band evolving and the way that we worked and etc, that once that was broken, I don’t think you can ever stitch that back together again. If the band was ever gonna get together and do anything, which I can’t see ever happening, it would simply be going over old ground. And that’s a real shame that that connection that sort of drive was literally dumped, which was a real shame. It was almost an act of musical vandalism to split the band up at the time.

We just discussed “Who Is The Five O’Clock Hero”, but the drums on that song, as an example, you’re really pushing the boundaries of what you could do to meet the needs of songs like that.

I’m not the greatest drummer in the world, but I did take a leaf out of Ringo Starr’s book. He realised that the song is the star, right? Not anything else. It’s not somebody trying to be the best drummer in the world, or the best bass player in the world, or the best guitarist in the world, which Paul certainly isn’t the greatest guitarist player in the world, for all his skills as a songwriter. None of us were really outstanding musicians in a lot of ways, but I think we were trying to be as inventive as we possibly could, so that we worked well together as a band. And that’s what bands are about, it’s not individuals, it’s actually working together, which makes that sound which makes it work. You can put the same cake together with different ingredients, and it isn’t the same cake. You can try anything else but that’s what makes a great band really. Bands like The Beatles, and dare I say ourselves, it is the sum of the parts that makes The Jam. There’s no other way of doing it.

And in March of 82, there was the release of The Gift. What are your reflections looking back on that album as a whole?

For a start, we went back to a more simpler way of doing it. We were very good at working with ourselves, we knew instantly whether something wasn’t working or was working. So of course, it was quite a straightforward album in as much as that, right there’s no overproduction. There’s not a huge amount of over thought on overdubs or what other elements we might want to bring into, it was only going right back to basics. And we’re just doing it as it may, as it was naturally felt as possible for us to do an album. And that’s what we ended up with. It’s difficult when you’re working on an album, to try and figure out what it’s going to end up like. We just did song by song like we always did. But when it’s finished, you look at it, you think, “Oh, I wish I’d have done something different or wish I’d done something else”. I think that’s always there. But by that time, we knew whether we were happy with what we were doing or not. For all its faults or whatever there might have been within it. You’re so close to the trees that you don’t see it. It’s very difficult to listen to an album with fresh ears, after having worked on it on the little miniscule bits of it that you do, to stand back from it and just listen to it. It’s nice these days, after not playing something for maybe five or 10 years, to pull it out and listen to it. It’s almost like you think, wow, it’s like fresh years to be able to do that. And you think, “Oh, it wasn’t as bad as I thought it was”, so that’s nice. And I think it’s nice when people say that they still like it, they still listen to it. I think it’s passed that test of time, it’s done all right. We were doing something right.

And in The Jam 1982, there’s some fantastic photos, many of which people haven’t seen before, some of which is you in the band, backstage on the coach, in the hotel. Some of those are by Neil ‘Twink’ Tinning. Have you seen all of those photos before? Did any of those come as a surprise?

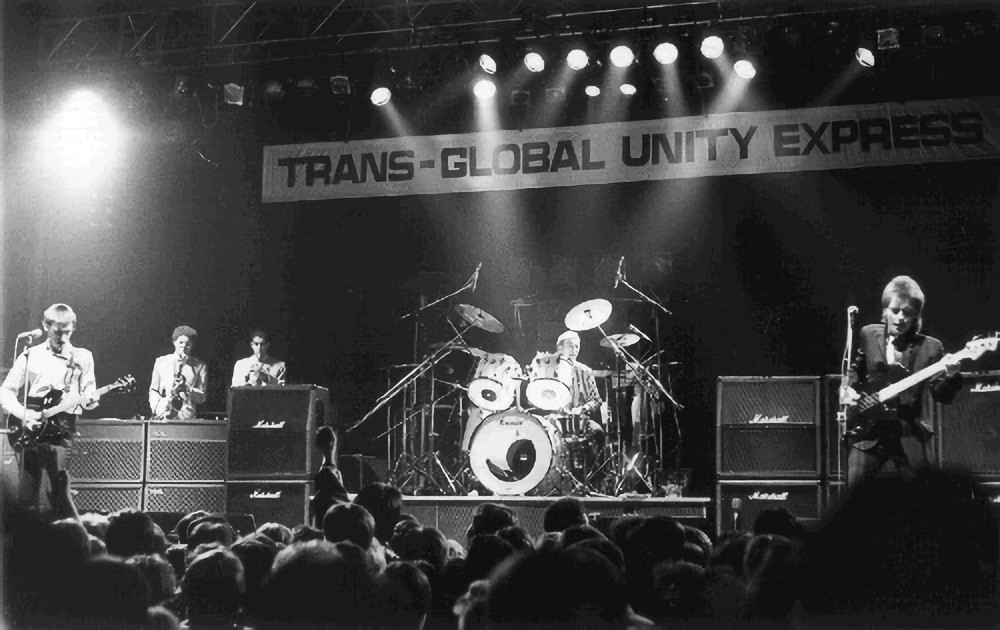

A lot of them I had seen, Neil, Twink is a good friend of mine. And he came on the road with us for the last 18 months of the band. He did a lot of photography backstage, which was brilliant because it wasn’t the sort of photo shoot for NME or anything like that where we all stand in a line and look miserable or whatever. These are more sort of candid shots. That one on the front cover, for instance, taken up in the corridor of the Sobell Centre in 1981. It was one of the last shows we did in 1981. We were just talking about what the second encore was going to be. For me it just conjures up memories. We did that a lot, we’d suddenly decide that the night had gone so well that we’d do a second encore or even a first encore. We hadn’t really thought about, well what should we do, what numbers can we pull up? What do we fancy doing? So those moments are really good. And that’s quite exciting because you suddenly think, you know what, we haven’t done this song for ages. Let’s just go and do it. And if you think “Oh, I hope I can remember how it goes”. That gives it an element of danger when you get into that situation. So that photograph revokes that for me anyway. But those sorts of photographs, they’re not really press shots as such. That’s a nice element. They’re taken from the inside out, which is great. I’ve got some really good photographs that Twink took, taken from behind the drum kit during a live show. So you see the backs of the band on stage, and the crowd all being lit up with the lights, which is not a view you often get when people take photographs of a live band.

I really love the photos. As you say, many of those are not staged press shots. They’re very natural, they’re backstage, unguarded moments. One thing I want you to ask you about is, in addition to the album tracks that you recorded, there’s some great 12 inch, B side tracks, some of which are covers, like ‘Move On Up’. That showed how you could all challenge yourselves and go into places that originally you didn’t necessarily normally go.

As you may or may not know,when we first started off, we started doing the clubs. We did all covers, and we became very good at covering other people’s material. It was a great insight into how other people arranged their songs and the little things, the musical tricks that they would pull to make it sound interesting. So when Paul found himself pressured by the record company because of the contracts, “Well, we need a single and we need it within six weeks”,and Paul would say “I don’t like writing to order. How can you just write a single that I’m going to be happy with as being single”, and that often reared its head. So sometimes we would just look at all the stuff that we had recorded for an album, and then just pick any old one. ‘Tube Station’ was picked like that for a single, it was the worst one on there, we thought it was the worst single to pick. And we did it, almost out of rebellion to the record company to say, “well, we’re gonna give you this one”, because it was difficult to record, we couldn’t get the arrangement right until the end. So we’re just going to give this one to you. But on some occasions, we would throw our mind back to days when we were doing cover versions. ‘David Watts’, you think, do you know what, that’s a great Kinks song. Not many people know about it, we’re good at doing covers, we’ll pull that one out of the bag. So that’s what we did.

It was nice to sort of rediscover that skill later on, if you like, and just think, well, I love these songs like ‘Move On Up’. There’s a few of them dotted throughout our career, but it was really nice to just pull them out because we could do them easily. That’s what we cut our teeth on musically. So it was just really great to pull on those sorts of songs. I mean, that was probably the main reason why we did covers, especially with ‘David Watts’, I suppose was the fact that we didn’t have anything else to actually release as a single. So it was a nice sort of filler. Maybe not filler, but a bit of relief from having the pressure on Paul to come up with a new song.

In the book there’s lots of contributions by people around the band and also, you obviously have a strong voice. You also get to be clear about the fact that there are some things that people assume are factual that are not. A little bit like ‘The Bitterest Pill’, because some people think that relates to the band splitting, but that wasn’t the case at all, was it?

No, it wasn’t. I always admired Paul because he can really look deep into himself and find the reasons for writing a song about something. There’s numerous occasions ‘Butterfly Collector’ was another one that comes to mind, when you listen to it, if you know the real story behind those songs. ‘Bitterest Pill’ had nothing to do with the band splitting or whatever. There were other reasons there. But to wear your heart on your sleeve, and explore that scenario and write a song about it. I think it’s a fantastic talent to be able to do that. It can be a real dodgy subject sometimes, it’s easy to write love songs etc. But I think people will relate again, I think it’s something that people relate to, because it rings true of life in general, these things happen.

Another thing that’s clear from reading is the final single ‘Beat Surrender’, a feeling that you didn’t want to go out on a down note. It’s a vibrant single.

It was a bit strange because we still had a little cache of songs that Paul had been working on. We’d done demos, we were all ready, really to record. And that was one that we actually wanted to use as a single, but some of them Paul had put in his back pocket and carried on into Style Council, so that they never really sort of surfaced as Jam songs but originated as Jam songs. So to pull that one as the last one was a bit odd. I must admit that it’s not my favourite of Jam songs, for all sorts of reasons. Maybe I’m too close to it emotionally. Every time I listen, I go oh, yeah, yeah. I can’t listen to that. [laughs] But we literally had to have something, we had a contract to fulfil. That’s why the last album was a live album, because there’s no way that given Paul’s persistence in calling it a day on the band, we could never have done another studio album, which is a real shame. Another thing I thought about was, we could have easily have done a world tour to finish off with, but we didn’t, we just decided to put a date on it, the end of 1982. To do all we normally did by doing a UK tour running up to Christmas. And that was it. The offers that were coming through to play in other territories to go to America or in Europe, Japan and stuff, especially Canada, that was our second biggest market selling records anyway, we just didn’t take advantage of at all. And I think that that’s a bit of a shame that we didn’t do that. And we didn’t go to Northern Ireland, which was at the time, a difficult place to visit because of the troubles that were going on there. But it just seemed like it was all pulled up a bit too short. We had only a few months to wind this thing up. It’s like running at 1000 miles an hour. And then somebody says, right, stop, you’ve literally got to put the brakes on, you’ve got to have a completely different attitude to how you go about things and what have you. So it was a very strange time.

I always thought that Paul would change his mind, the shows were going so well. The reception we were getting was very emotional on that last tour. You think surely you’re not going to throw the baby out with the bathwater now. But there it was, that was it. I mentioned in the book, this was 10 years of my life, from the age of about 16 to 26. When that was my reason for getting out of bed was the band, was everything that was put into it. I think Bruce felt the same way as well. John certainly did. The band was John’s baby. He’d got us all the work in the early days and did a lot for all three of us up until the point we got signed. So he was devastated as well. So it was a shock all around. I think Paul was probably the only person on the planet who actually thought this was a good idea. But there you go. Everybody had their different reasons for wanting the band to continue except for Paul. And I think his reasons were dubious. But like I say we were grownups. We could live with that scenario. And we certainly did. I think we stepped up to the mark like we normally did. We did a great job of playing those last shows, and recording the last few things that we needed to record. And to get on with our lives. I think all three of us are very grateful for what The Jam did for us. It set a tone for the rest of our lives for all three of us. So in that respect, absolutely no complaints or no regrets whatsoever. I don’t know whether Paul quite feels that way because he would not talk about The Jam or play Jam music at his concerts or anything after the split. He wouldn’t even talk to me and Bruce [laughs], which was quite a source of bewilderment for both of us for a number of years until the penny dropped as to why he wouldn’t. I’m sure there’s a lot of bands that that sort of scenario has happened to in the past, and I’m sure it won’t happen again. Maybe there’s a little fable in there somewhere. I don’t know.

Those last batch of live shows must have been quite emotional, because you had that build up, Paul saying that he wanted to leave in the summer. And then you’ve got a series of shows, building up to those December shows. And there’s some great material that got released as extras to The Gift, Live at Wembley, third of December. ‘To Be Someone’ sounds brilliant. And the last show in Brighton must have been really strange.

It was. Normally, when we finish a tour, we’d be buzzing about what was to come, what were the new things that we were going to be doing next. And there wasn’t any of that. But I remember looking at the crowd, especially on that particular night, and seeing on the faces of everybody there exactly how I felt. It was almost a sort of disbelief. The connection we had with our favourite Jam fans was very strong, we didn’t take them for granted at all. We certainly didn’t at that time. There was no them and us situation. And we always liked to talk to the fans and treat them with just as much respect as I think that they treated us. So there was a very strong connection. I don’t know whether that still exists today with Paul, I don’t know whether he still tends to. I hear a lot of disgruntled people saying “Oh, he wouldn’t see me, he wouldn’t come out and sign this and that and the other. So I don’t know, really, whether he still holds those sorts of values that The Jam had. But I think one of those values was to be sort of honest and upfront with people about things. And I think this is one reason why it annoys me so much. This sort of fairy story as to why he left. I don’t think that’s particularly honest, I don’t think it was particularly straightforward with the fans. Because no band is anything without the fans buying the tickets, buying the albums, coming to the shows. And I think if you lose sight of that, you’ve pretty much lost sight of a lot of things. Like I say, Paul hasn’t actually spoken to me at all, since. You think, what on earth did I say? So I don’t think it’s necessarily on our side of the fence. I think it’s more from him. There’s something odd going on there. But I think a lot of it was probably to do with mismanagement. And I’ll just leave it at that. Which is a real shame, to have to resort to that to sort of cover things over. Maybe we’ll never know Paul’s real reasons. But I just know, I get this gut feeling that the reasons we were given were rubbish, absolute rubbish. It just doesn’t sound logical, sounds nice in a fairy stories sort of way, but doesn’t bear much in the face of reality.

Just a close, Rick, a fantastic book and given you’ve got the mix of the points from yourself, memories from people around you, those fantastic photos and the setting of the political context and the weather, it really does get you back into 1982. I encourage everyone to get it.

Thanks for saying that because it’s always difficult to know whether it’s got the right elements and whether it’s done the right things. I just hope people, Jam fans or anybody who reads it, find something in it of value. It was an odd scenario. Thanks for letting us do the interview. Brilliant.

It’s a pleasure. Maybe that’s the theme that comes out then and it comes out now, is that connection. 40 years later, that connection is still as strong, especially for the fans that were young, and in their teens, 40 years ago, and now around 60 or whatever. They’ve still got that memory of that special period of those five or six years of The Jam as well.

It’s just the fact that we’re still talking about it, and that people are still interested in it, the records are still selling. I have to pinch myself every morning and think well, wow. We didn’t set out to do that, we set out to be for ourselves, we set out to be a great band. That was it, that was all, like playing live and touring. That’s quite a simple ambition as far as we were concerned. So to have this still being listened to all these years later just blows you away.

Further information

Rick Buckler is celebrating the publication of his new book The Jam 1982 with events around the country. Dates up so far are Gillingham, Glasgow, Dundee, Birmingham, Wimborne, London & Penzance. Tickets and information: thejamfan.net/events/

Also available: an audio version of this interview with Rick Buckler and Bruce Foxton podcast interview