Peter Daltrey and Mark Mortimer

Peter Daltrey of Kaleidoscope/Fairfield Parlour speaks to Jason Barnard about his life in music, and new collaboration with Mark Mortimer (ex-DC Fontana) to produce some of the most adventurous and exciting music of his career.

Your new album Running Through Chelsea (credited to Peter Daltrey and The Know Escape), combines your usual high bar for lyrics, and Mark Mortimer’s fondness for the inventive 60s sound with a psychedelic feel. So it’s a really good fit. How did your collaboration start?

I’ve known Mark for a few years and he contacted me, wanting me to contribute just one line to a song he was working on, which I did. He came here and I did a vocal and off they went. And I didn’t hear from him for probably a couple of years. Probably 18 months ago, Mark contacted me, he sent me a track and said, “Do you fancy working on this? I need some lyrics.” His music is very inventive. The first one was ‘Time and Tide’. He and Michael Tyack, who he works with, had already done it. It was basically an instrumental and he said that he’d quite like me to find a space in it to contribute a couple of verses. It’s very tricky, because it’s a very liquid ephemeral sort of arrangement. It was difficult to find my way in. But eventually I wrote a couple of verses for that, recorded it here and sent them off to him. They were happy with that. And he said, let’s do another one. Because if a collaboration is going to work, that’s where it starts.

Once you start one or two songs, you realise there’s something going on. So I said to Mark just keep sending me stuff. But the way I like to collaborate with people is they send me a basic track, nothing too fancy, not lots of fiddly stuff on it. He sent me the tracks just with drums, guitar, bass, and perhaps some strings or something. Just chord sequences. And then I sit down and listen to it over a couple of days or a week and work out a melody line through the chord sequence. Then I work out the lyrics. Sometimes it comes the other way around, you’ve got the lyrics and the melody coming together quite quickly. And then I would record a scratch vocal here and send it off to Mark and he’d say, “Yeah, let’s work with that.” I’d then do a proper vocal with harmonies or whatever, send them back to Mark and then he would start adding all this wonderful instrumentation either himself or others. Mark’s No Escape is like a collective where he’s got a big distribution of musicians that he knows all around the world that he’s worked with. And then if he’s got particular parts that he wants like sax, organ, drums or whatever, he calls them in. Nowadays, you don’t all have to be together in the studio. It’s a shame but on the other hand, it’s very beneficial because we will all record our parts and studios thousands of miles apart. And that’s how it comes together. Eventually we end up with what we consider a finished track which we’re happy with. Then Mark sends it off to Donald Skinner or Rick Reill, who are producing various different songs on the album. We then arrive at what we all consider to be a finished track.

Was it always the case that you’d had a piece of music that was presented to you?

I always used to write the lyrics first. I was a 12 year old frustrated poet. I’ve got reams of that stuff upstairs. So that developed when I met Eddy Pumer. He asked me to join the band. We quickly realised we weren’t going to be able to exist on covers and we had to write our own. I don’t know why, it just naturally fell to me to write the lyrics. To spark Ed off, I used to write the lyrics and send them to him, and then he’d work out the melody. In the late 80s or 90s after White Faced Lady, the last album which eventually came out, there was a lot of talk in the band that we must get back in the studio. But very frustratingly for me, nobody did anything. When you’re a creative person, you can’t stop, it keeps bubbling up all the time, and you want to do stuff. And I’ve been frustrated for years not being able to do anything on my own. But when the band said, well, let’s get back in the studio, it didn’t work out. I thought, right, “Ok, I’ve got my own music”. It was at the time when you could start doing that on computers, there were digital workstations, you could work on keyboards, samples, everything like that. So incredibly, I found that with my very basic musical abilities, I don’t class myself, as a musician, that I can use a mini keyboard and pick out a bass line, strings and everything else as I do it one at a time. And then of course, I can write the lyrics and do the vocals over that. I did that for years. I’ve done 18 albums, some collaborations but quite a few solo albums. When I started collaborating with people, I always found it easier for me if they sent me the track first. And then I started writing the lyrics to it. That’s what I do now. I’ve worked with marvellous, incredible musicians and it’s very humbling to work with these people. It never ceases to amaze me how expert they are at the instruments they play. And that’s just the way it’s worked out, they send me the track and I work out the melody and the lyrics.

So post Kaleidoscope/Fairfield Parlour, when you’re working with a collaborator like Mark, you’ve got that added element of two creative people who can bounce off each other.

Very much so. Mark’s tracks are inspirational. Then when he finishes them off it is breathtaking. I love working with other people. Damien Youth and I gelled straight away and that was very much acoustic and very basic home recording. I’m very proud of the songs that Damien and I wrote. Damien is a great singer and songwriter. His song ‘Broke Heart Singer’ is a beautiful song. The other great collaboration I had was with Mike Dole, he writes some lovely music as well. I use a local friend of mine, Derek Head, who provides saxophone to some of my tracks. He’s a brilliant player.

Damien wrote to me and suggested I work together with The Asteroid No.4, that’s another unusual album. A collaboration like that really stretches you. If I was left to my own devices, I’d be writing twee gentle stuff. So collaborating makes you write in a different way, it does push you further. And the album with The Asteroid No.4 certainly did that. When I did my first tour of the USA, they had the tracks ready, we recorded the vocals in LA at Robert Bartholomew`s Studio. I’m just flattered that these very talented young musicians actually think about working with some old bloke like me. [laughs]

You mentioned ‘Time and Tide’ earlier. Songs like that and the title track seem to be going back through your mind over events and feelings and emotions. Is that something you recognise?

[laughs] At my age, you tend to do that, Jason! ‘Time and Tide’, we’re running out of time. Yeah, I don’t know where the lyrics are coming from. But there’s elements of that in there. There’s also a lot of fun. I think they’re great tracks. ‘No Girls On Mars’, there’s a hell of a lot of humour in that. ‘Bukowski’s Tambourine’ is pretty much autobiographical, writing poems, sending them out, they come back. Bukowski is an incredible writer, somebody I look up to. If you look up ‘Elisa Lam’ that will explain the lyrics for that song.

References to London, was that going back to the 60s?

Very much so but I don’t want to make an album that’s psychedelic. Fairfield Parlour wasn’t psychedelic. There was a little brief window of about 18 months in musical history. That was psychedelia, and we just happened to be recording in that window. So we got labelled forever as being psychedelic. But Ed and I never went into studios and said let’s be psychedelic, it didn’t work out like that. We were just fanatical songwriters. Dan and Steve were with us all the way. But when our writing changed, we realised fairly quickly that we had passed that stage and had to move on. That’s one of the reasons why we split from Fontana and moved to Vertigo, a progressive label. I don’t know how you specify From Home To Home, it’s a mixture of styles and it matured a lot from Tangerine Dream. If there’s one thing that I was proud of with writing with Eddy. It’s that over the years of our songwriting, we developed and matured. If you listen to White Faced Lady it bears very little resemblance to Tangerine Dream. But of course, we get labelled as psychedelic even now and that’s fine. I don’t mind. It’s nice to be remembered for something in particular. But I don’t want to make that album. I know Mark is very keen on the psychedelic side of it, but it doesn’t intrude on his music. There are elements in his music but it’s not overt. But the references to London in the 60s are just inevitable really. I was born and grew up in London; born and started my life in Bow then moved to Harrow. And then lived the whole of the 60s there. Ed and I worked right in the heart of London just behind Regent Street, Oxford Circus, from 1964 to 1969.

The creativity at the time seems to be one of the themes. People exploring new sounds and ideas?

The creativity at the time seems to be one of the themes. People exploring new sounds and ideas?

London in the 60s was incredible. I don’t want to sound like an old hippie but if you could almost feel it in the air. You’d get up in the morning and wonder what the Beatles were doing or Terence Stamp. Was he making a new film with Julie Christie? Who is David Bailey photographing today? Francis Bacon? What picture is David Hockney working on? Mary Quant, what is she designing today? Where’s Twiggy? It was like these people just exploded out of nowhere. The creativity in London at that time was extraordinary. To be part of it was a real privilege. A Lot of it does start with The Beatles, you can’t you can’t take it away from them. We loved The Stones. But for Ed and I and the band, it was The Beatles all the way. We were obsessed with them. We weren’t trying to write like them or be like them, but of course, bands were springing up like mushrooms overnight. There was just so much influence from that one band. So we had all these bands coming up. And then you had the artists, the photographers, the models, then the films, 2001, Far From The Madding Crowd. It was bubbling under all the time. I was conscious of what was going on, right in the heart of London, then the clothes changed, music changed. Fashion, just exploded, we were all sick of the 50s. I was born in 1946, the 50s when I was growing up were just grey and drab. Sundays in the 50s were absolutely dire. Nobody had anything to do on a Sunday. There were no shops open. Television was boring, there was only one channel in black and white. You could still walk around London, see bomb sites, piles of rubble. So to find in 1962/63, when The Beatles started, things were changing. But as soon as the fashions changed, there was just colour everywhere.

Your label Philips, weren’t they trying to position you as the next Beatles?

Our producer, Dick Leahy, wasn’t much older than us to be honest. Every producer in London was trying to be as good as George Martin. We heard Dick was going around London very excited to say that he thinks he’s found the next Beatles. I don’t go on about it, because there must have been a dozen producers around London all saying the same thing to people. The whole thing centred on the songwriting, that’s where it came from. We got our first contract through approaching a publisher rather than a record company. We sent off the demos to the record companies and never got them back or anything. Somebody I was working with said “Why don’t you go through a publisher?”. And that’s how we got our contract. We went to see Flamingo Music and Dave Carey there heard ‘Holidaymaker’ and called in Dick Leahy from Fontana and said you must listen to this. And Dick said to us “Do you want a recording contract?” And that’s where it started, we began recording in January 67, ‘Holidaymaker’ and various tracks. But then Ed and I were writing all the time, we never sat back on our laurels. One day we went to see Dick. We said we had a new song and played ‘Flight from Ashiya’ and he said, “Well, you’ve got to get in the studio today”. We went straight in and recorded it. And he refused to put up ‘Holidaymaker’ on the A-side. The publisher had said ‘Holidaymaker’ needed to be on the A-side and it would have come out in summer 67. And of course, it might have been a hit if it came out in the summer. It was lyrically perfectly placed to be a hit. But Dick changed his mind. He said “No, ‘Flight from Ashiya’ is too good. It’s too unusual. We need it as the A-side.” I understand but of course in hindsight, it was probably wrong.

We should have grabbed a mini hit with ‘Holidaymaker’ and then got something else. Although if you’d have followed up with ‘Flight from Ashiya’ I think it would have still flopped, because if you’d have established yourself with that, they may have wanted to hear more pop music rather than something a bit more esoteric.

The four albums of Kaleidoscope and Fairfield Parlour, all of them in their own way stand on their own and are peaks. It seems strange that you never broke through despite the quality.

The reviews were always very good and we were very proud of the records. Dick Leahy was always upbeat and expected them to go places. But the fact was that we found out after a couple of years, that with Fontana, we’d signed to the worst record company in London. Their reputation was of terrible distribution. They just couldn’t get the records in the shops. We used to get letters from fans saying, “We love your music. We love that single. We went to the record shop and couldn’t buy it so we bought something else.”

But there was an added problem that hasn’t been brought out much. Dick Leahy’s boss was a guy called Jack Baverstock. He was old school, one of the suits at Fontana-Philips and he had under his wing, Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Titch who already had a string of very good pop singles. He never rated us. Jack Baverstock was never a friend of ours. We were never close to the guy. He always looked down his nose at us. I don’t think he was giving Dick Leahy the full backing which he should have done. He probably held back on production numbers, the number of records made. And on the distribution as well, because I reckon if a Dave Dee record was coming out, he favoured that and press promotion, not ours. So it wasn’t promoted. There were only tiny little adverts in the music press. It wasn’t promoted and it wasn’t in the shops. It carried on as well. The trouble was we decided with our manager, David Symonds, to re-sign with Vertigo which was still under the Philips umbrella. They assured Dave,they said, “No, there won’t be any problems with distribution. We promise you, we’ve sorted all that out”. But nothing had changed.

We managed to get on Top Of The Pops for ‘Bordeaux Rose’. It sounded like a hit single. Dave said “We’re already in the lower regions of the charts. It can almost be guaranteed if you’re on Top Of The Pops, your record will have a big leap. There’s no doubt about that.” We were all very excited about it. We went on and it was broadcast – and our record went down. The sales weren’t there because the records weren’t there and that played out for Fairfield Parlour and Kaleidoscope. Some bands make it, some don’t. We obviously weren’t meant to make it. It was infuriating at the time and very depressing. When the band broke up, it broke me really. But life goes on. Here I am now still talking about it. So I’m quite happy.

The sound of the group’s records clearly developed and evolved. I assume it was a similar sort of approach playing live?

Not particularly, no. We had a lousy agency. We were assigned to the Noel Gay Agency. They didn’t have one foot in the past, they had two feet in the past! The venues we should have been playing on a regular basis were…

The Roundhouse.

Yes, the Roundhouse, UFO and Middle Earth. Kaleidoscope should have been at all of those venues playing, almost on a rota, like the other bands of the time. We never got a gig at any of those clubs. That’s ridiculous. The agency didn’t know what to do with us. They should have been pressing those venues. Our history might have been different, just from that one move. If we’d have started playing those three venues, our whole history might have been different. But we didn’t. We went on the college circuit, which was very good. And clubs, like, Mothers in Birmingham, we always went down well there. But we loved writing and recording. And of course, as soon as we hitched up with David Symonds, there was a lot of recording going on as well. We had plenty of gigs at colleges and universities, which was fine. The approach to the performance was tricky as well, because you’re producing psychedelic records with Kaleidoscope and with Fairford Parlour there were string arrangements. A lot of this stuff you couldn’t reproduce.

The Beatles didn’t even try it.

No, that’s right. The Beatles realised the limitations of live shows in 66. It’s a factor with bands, you could produce great records, but I don’t like live albums. It’s a bit different now because of the equipment and extra stuff behind the scenes, which can add to the performance: screens and the lighting. But if you’re going on stage and if you haven’t got all that stuff with you, it can diminish the audience’s expectations. The best music comes out of a good studio session.

You said to me a decade ago that you weren’t even that keen on the BBC sessions material either.

No, because they were produced by people in brown coats. All the knobs on the equipment were Bakelite and [says with English elocution] “Okay, come on chaps, you get a move on.” You might have an hour in there, and you’ve got to do three, four live tracks for a BBC broadcast. So, in the end, the people in the studio would say, “Well, have you got a backing track?” I don’t know if I ever listened to the BBC album. I know people like it because it’s a slightly different versions, but it’s not for me.

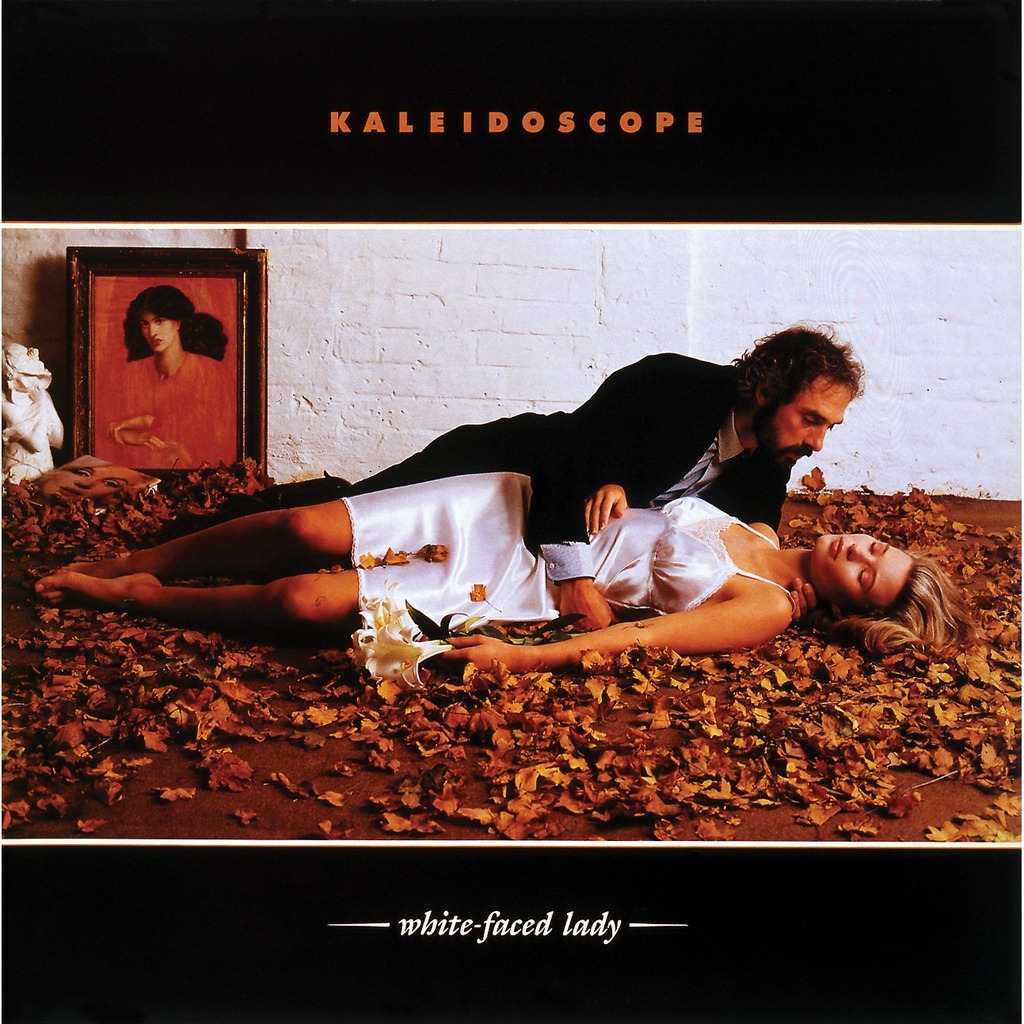

You mentioned earlier about the dissolution of Kaleidoscope/Fairfield Parlour. It must have been a really tricky period, because again, there’s a strong case that you’ve done your best work with White Faced Lady. It’s a masterpiece. You didn’t get it out, did you?

Well, at the time, we had some really serious band disasters as Fairfield Parlour. We did the Isle of Wight Festival. We wrote the theme song and it was ignored, we performed there. It was going to be the absolute highlight and that fell apart. We had a concert supporting Pentangle at the Royal Albert Hall and that fell apart because somebody buggered up our equipment and all the knobs were turned in different directions. We had no sound when we walked on stage, which is the most humiliating experience of my life. All these disasters and the lack of success, it can’t help but dull your spirits. But even so, Ed and I carried on writing, and we came up with White Faced Lady. Dave was for it, the record company was for it.

Then we started recording, but it was very difficult, because we were all tense. We were all worried about the future. And yet there we were in the studio recording these lovely songs, telling this story. And it was very important that we got it right. Our most important album of our career, we knew that when we were doing it. We also knew that it was going to be a double album. So it was inevitably a big release, and it had to be right.

There were tensions in the studio with various things which are irrelevant now. That didn’t help. You know the story, it didn’t come out. The guy at Vertigo, Olav Wyper said, “Yeah, we’ll do it”. And then he left and went to RCA. So we followed him to RCA and said, “Can you do it?”. He said “I can’t do it here either”. Then the band broke up and it just sat on the shelf. Fortunately, unknown to us, while the band was defunct, our reputation was beginning to grow, probably because of Tangerine Dream. And then people discovered Faintly Blowing and From Home To Home and realised there was more to us than just that. And then the climate was right to put out White Faced Lady on our own. And then the reputation just kept going and now we’re on a nice plateau.

Even in the decade since we’ve spoken there’s continued to be reissues and you’ve played live and toured. To have that respect and reverence must be gratifying.

It is. [laughs] When Neil Martinson rang me from America and said “You must bring the band over”. Ed and Dan were sadly unable to do it, because they weren’t well so it wasn’t going to happen. Then six months later, he rings me again and asks me to come over. I said “Don’t be silly, I can’t do that”. My wife very wisely said, “If you don’t go you’ll regret it for the rest of your life”. Of course, she was absolutely 100% right. So I was on a plane heading to America to appear for the first time on stage in over 40 years, with a band that I’d never met before. They turned out to be wonderful musicians and I had a great little mini tour of California. It was very heartwarming. I loved every minute of it and the best part was meeting fans, young people who are really appreciative of the band’s history and the records that we put out. That was an eye opener. I came back and we with the help of my new manager, Chris Barnett, put together tours of Europe, Scandinavia and Britain. And then we went back to America in 2013 and then finished up with some gigs over here. And I packed it in in 2017, at the Hoxton Hall in Islington. It was great. My British band, which was made up mostly of The Trembling Bells and Seb Jonsen from Scotland. Incredible musicians, great fans of the band. So we would perform on stage and it would be almost note perfect, really. It was so thrilling to be playing these old songs with these young musicians behind, knowing you could trust them to get everything right.

The records have also been reissued several times. I don’t know whether you’re aware, but we’ve signed to a British label, and we are working on a definitive box set that will bring out everything we’ve got in the vault. The first box will be the first four albums on vinyl. And then there’ll be a second CD box, which again will be the four albums plus the BBC one, The Sidekicks, there’ll be live stuff, all the demos that Ed and I recorded. Those demos I recorded in Ed’s bedroom when he first played me the songs. ‘Diary Song’ is a demo with Ed singing it on his guitar which people are going to find very interesting. There’s other songs on there, which Ed and I really loved, which never made it to the studio. ‘Mecklesham Bay’ and ‘Stolen Shoes’, songs like that. Because they never made it to a band studio session I’ve actually recorded those myself, and I’m hoping that they will be included in the box. That will be an ongoing project. There’ll be the two boxes out, but I suspect after that the label will reissue special editions of various albums as well. So it’s going to be the closing chapter of the band’s career, with these amazing boxes coming out. There’s going to be a lot in it, a book, posters, little bits of memorabilia. It could be as much as two years away because there’s a lot of work to do, but it’s very exciting to me. Dan and I can’t wait. We’ve just got to stay alive for another two years! [laughs]

There’s the material in the 60s and 70s, which is wonderful. But you’ve always got that muse to push forward and keep being creative. And that’s what came out with the Running Through Chelsea album.

Like I said before, if you’re a creative person, you can’t stop, it’s just in your blood. With the injection of inspirational tracks from Mark, it’s just brilliant. There’s songs on there that I wish I’d written, 50/60 years ago. It’s the same with my two solo albums that I recorded during lockdown. There are many tracks on there that have a Kaleidoscope-Fairfield Parlour feel to them. Inevitable as it`s still me writing and singing them. It’s quite refreshing to know, I can still do it. You just need a spark to write a song. You hear somebody say something or there’s a headline, and it just kicks it off. I`ll keep doing it as long as I can.

That’s a great way to end, hopefully we can reconnect for the next project.

Yes, we’ll keep in touch. At the moment, we’re very pleased with what we’ve done but we don’t know what the response is going to be. We’ve almost got a couple of songs for another album. I also have to thank Roger Houdaille at Think Like A Key Records. Great to have the album out on CD and digital, but to have vinyl is wonderful. Vinyl sleeves are almost like works of art. Then there’s the Kaleidoscope-Fairfield Parlour box set that’s going to be very special,. So Dan and I – there’s just the two of us left now. We get together a couple of times a year, we go through all the old stories. He’s a wonderful guy. But we both miss our band brothers, Ed and Steve. It`s not the same without them. But music is a wonderful because it lives on after we`ve all gone. I draw comfort from the thought that maybe in twenty or fifty – or even a hundred years someone might stumble across a holographic file of ‘The Sky Children’ and enjoy listening to it enough to investigate who that band was…

Further information

Running Through Chelsea by Peter Daltrey & The Know Escape is due to be released on 31 March 2023 on vinyl, CD and download.

The Strange Brew says:

From start to finish, Running Through Chelsea takes the listener on a journey through various musical genres, evoking nostalgia for the psychedelic era, while also offering a fresh take on the spirit of the 1960s.

The album opens with the title track ‘Turn On Your Radio’, which kicks off with a Lucifer Sam style riff with Peter Daltrey’s lyrics evoking the modern social and digital world. From there, the listener is taken on a trip through lush soundscapes and intricate melodies, Mark Mortimer’s arrangements add a layer of complexity that elevate Peter’s ability to craft insightful lyrics. This is highlighted by sumptuous folk ballad ‘Time And Tide’, a beautiful piece of production that showcases Peter’s emotive vocals. ‘Running Through Chelsea’ is a remarkable moving elegy for late 1960s London scene.

In conclusion, Peter Daltrey, Mark Mortimer and The Know Escape have produced an album that is both timeless and fresh, a standout album that will be remembered as one of the most adventurous and exciting releases of the year.