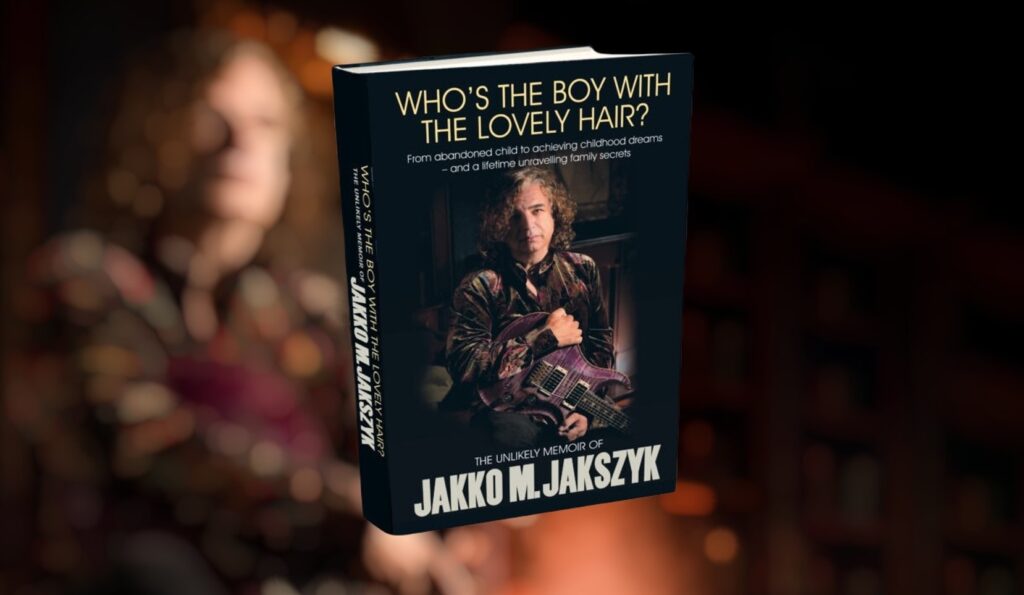

Jakko Jakszyk (Credit: Tina Korhonen)

Jason Barnard speaks with Jakko Jakszyk, lead vocalist and guitarist for King Crimson, about his memoir Who’s The Boy With The Lovely Hair?. From growing up as a music-loving teen to performing on stage with his childhood heroes, Jakko reflects on themes of identity, adoption, and the serendipity that shaped him. With stories spanning encounters with Michael Jackson, Cliff Richard, and even a brief stint with The Kinks, Jakko shares both the deeply personal and the surreal moments of his career. The interview touches on his relationship with his adoptive parents, the search for his biological father, and the profound exploration of self, woven throughout his memoir.

We spoke four years ago for a double podcast around the time of your album Secrets and Lies. Your memoir, in a positive way, is uncategorisable, given the range of themes it covers. Do you think identity is at the heart of it?

The very opening chapter, which is now called the Prologue—the first thing I wrote—was a kind of statement of intent. It starts in Bearden, Arkansas, and it’s like, “How the hell did I end up there?” It’s that really weird thing where, as a child, I’d imagine what it would be like to have siblings, but the last place I imagined was the Deep South, with its undercurrent of racism. And, as I say at the end of that chapter, you go through all these different stages of anxiety, loss, and abandonment, and you build up this armoury to help you get through it. Then you find yourself thinking, “Had I not been adopted, I’d have been brought up here.” It really does ask that fundamental question: who are any of us? There’s the whole nature-nurture thing—how much of the person I recognise as myself would exist if I’d grown up there? What would I sound like? What would I think? Would I have the same hideous views as some of my relatives? I certainly wouldn’t be in King Crimson, that’s for sure. So, yes, the opening chapter sets that up, and later in the book, I reflect on it—36 years later, I’m standing on stage in front of 120,000 people with the band I loved as a kid, thinking, “How the hell did I get here? This is mad.”

Something you said last time really struck me. People see your name and assume you’re from a Polish background. When Brexit happened, you commented on social media, and people piled in. In reality, you have an Irish background—not that it should matter—but it highlights the sheer hypocrisy of the situation.

Absolutely. I was born in London. My mum was Irish, from County Mayo, and my father was an American serviceman who I never knew. I only found out about him right at the end of the book, which is why it ends where it does, with that search for him. But you’re right—after the Brexit result was announced, I foolishly posted about the Polish Centre, which had been set up partly in thanks for the Polish contribution to the end of the Second World War. I’d taken my adoptive father there when he was older, for lunch or whatever. After Brexit, the place was completely daubed with racist graffiti. I posted about how saddened I was by it, as I had a nostalgic connection to the centre.

Then, of course, your friends comment, and it gets shared, and soon people you don’t know start writing things like, “We won, you lost. Why don’t you fuck off home?” I’m sure they didn’t mean Highgate or Croxley Green. But it’s hideous, isn’t it? We’re all human beings. The point is, had I been brought up in Bearden, Arkansas, I would have thought one way. Had I been brought up in Gaza, I’d probably be Muslim and think all sorts of other things. So, there but for the grace of whatever go any of us.

The historical aspect is fascinating, especially on your adoptive father’s side—your adoptive grandfather was from a German background.

Yes, he was ethnically German but living in Poland. So, my father, who was Polish, was deemed racially pure enough to be conscripted into the German Army. There’s a photograph of him in a Nazi uniform. I’m really indebted to Al Murray, the comedian, who has a degree in modern history from Oxford and has written several detailed books on the Second World War. He also does a podcast with historian James Holland. I had all these interviews with my father that I recorded for a piece I made for Radio 3, but only a tiny bit of it was used—just a few minutes. I’ve got hours of these conversations, which I revisited for the book. My dad was in his 80s, so he couldn’t always remember exactly when and where things happened, but Al and especially James Holland were able to help. I sent them some of my father’s documentation, which is also in the book, and James said, “I know exactly where your dad was, what battalion he was in, and what battalion he was meant to be in.” It was fascinating—it really put flesh on the bones of that story and brought that chapter to life for me.

Your adoptive mother’s journey is equally fascinating—she was French, wasn’t she?

Yes, her story was equally melodramatic and heartbreaking. She was abandoned by her mother and ended up living in Paris with a mother she had never met. Then she had to flee Paris because her new stepfather was a communist. Incredible stories.

You also described, in the ’90s, when your mum had Alzheimer’s, those glimpses of memories she had of the past.

Anyone who’s had a close relative with Alzheimer’s knows what an incredibly cruel disease it is. There’s an advert on TV now that says it perfectly—“My mum first died, and then she died, and then she finally died.” You do lose the person you knew long before they physically go. The title of the book is based on that.

The last time I saw my mum, we had a long chat, but it was very disjointed and strange. All her memories, which had once been in chronological order, had started to become jumbled. Even within the same sentence, she would talk to me as if I were both a child and an adult. It was very disturbing. The day before, there had been a trip from her care home into London to see the Christmas lights, but she had no memory of it. When I left, the manager called me in and said, “She did go on the trip—she just doesn’t remember.” And that’s where we were—we were just managing moments.

As I was leaving, my mum came into the room. I could tell immediately that she had no idea who I was, even though we’d just spent two hours together. A care worker came in and said, “No, no, Ms. Jakszyk, your room is over here.” As they walked out, my mum turned to the care worker and said, “Who’s the boy with the lovely hair?” That was the last thing I heard her say—she died that night. And that’s why the book is titled as it is.

As a child, your relationship with your father seemed difficult.

Yeah, and then, of course, later on, when I learned what he went through, all of that makes a kind of sense. It wouldn’t have made sense to me as a kid—you’re just responding to what that is. And it generates a personality that’s full of fear. I was absolutely petrified of him. And I felt very isolated and lonely. And then you find out you’re adopted, and you think, well, maybe it wouldn’t have been like this, or wonder what it should have been like.

In your teens, you developed a passion for football and music. Can you tell us about the live music experiences you had during that time?

I was very fortunate. The area I grew up in—the home counties, Watford and Hertfordshire—had loads of venues when I was a kid. There was the Technical College, Watford Town Hall, the Top Rank, and a little club called Kingham Hall, which only held about 300 people. I saw Peter Gabriel-era Genesis there. I must’ve seen them about three times. I was exposed to some amazing music from that era.

Coming back to your career, you’ve played in various groups and bands, and the culmination was performing on stage with King Crimson in front of 120,000 people. Yet, earlier in your career, you were dropped by record labels and played smaller gigs. That’s quite a contrast.

That’s life, isn’t it? We all have experiences—not necessarily in the same field as me—but in our lives, there are opportunities you sometimes ignore, sometimes grab. You make decisions you might regret or can’t believe you made. And then there are moments of luck. It’s all luck, really. Self-help books often tell you how to be successful, but they tend to overlook luck. Fortune is just being in the right place at the right time. It seems to come out of nowhere.

Along the way, you’ve met some fascinating people. There’s even a story where you ended up at the recording of Michael Jackson’s Bad album.

Yeah, that was back in ’83 or ’84. I was being produced by Peter Collins, who sadly passed away recently. Peter eventually moved to America and produced albums for Rush, but in the ’80s, he was doing all kinds of pop stuff—Alvin Stardust, Tracy Ullman, Musical Youth, and the first two Nick Kershaw albums. He was brought in to produce some of my stuff. For one track, he said, “I think it’d be great if we had some brass on this.” I said, “Oh, I know a couple of trumpet players.” He replied, “No, I mean the brass section—Jerry Heys, Quincy Jones’s horn section.”

So next thing I know, we’re on a plane to Los Angeles, working with the Jerry Hey section, these incredible musicians. They loved playing on my stuff because it was different, and I encouraged them to be a bit left-field. Jerry wrote some fantastic arrangements. I became friends with Larry Williams, a saxophonist and keyboard player in the section. We hung out whenever he toured the UK, and I’d stay at his place when I was in LA. We’d go out together, and I remember seeing Michael Brecker with the section at a jazz festival at the Hollywood Bowl.

One day, Larry invited me to a session and said the guys would love to see me. He didn’t mention it was a Michael Jackson session! When I got to the studio, there was loads of security, which is unusual for recording studios. They’re typically faceless buildings. After explaining I was a friend of Larry’s, he came to get me, and we walked down a corridor where Michael Jackson was leaning against a wall. I spent the day with him, and in my book, I tell a ridiculous story about how Michael suddenly started chatting with me about my shoes. He was quite taken with them! I knew I was in the presence of someone like the ’80s version of Howard Hughes—you don’t bump into people like him at the local Sainsbury’s.

You’re also partially responsible for the late-’80s hit Stutter Rap.

Yes, I dabbled in comedy and moonlighted in this group as a grotesque Italian character. We did a number of shows, including a narrative set-piece at the Edinburgh Festival. It was me, Roland Rivron, Simon Britton, and actress Kathy Burke. We performed at a venue called the Gilded Balloon, which had a late-night bar where all the comedians gathered. That’s how I got to know so many comedians.

One of them was Tony Hawks, who had a band called Morris Minor and the Majors. They had a song called Stutter Rap, which they performed on Saturday Live. It created such a buzz that Virgin Records offered them a deal. They insisted I produce it because, being a musician, I understood both music and comedy. I did it under a pseudonym because I thought, if this becomes a hit, I don’t want to be associated with it!

There was also a time when you briefly deputised for Dave Davies in The Kinks.

Yeah, I was in the Kinks for a week. It was 1994. I was in Level 42, and one Sunday the phone rang. This was pre-internet, pre-mobile phone. I got a phone call asking about my availability for the next week or so. I said, “Oh, yeah?” He said, “Ray Davies has asked me to call you.” I said, “What, from the Kinks?” He said, “Yeah.” I asked, “OK, why?” He said, “The Kinks have got some live stuff, including a radio broadcast live on Radio 1, and his brother Dave is ill. He wanted to know if you might replace him.” I said, “Are you sure he asked for me? Because I’m not that kind of guitar player. I was in Level 42, a fusion-y kind of thing.” He said, “No, he definitely asked for you.” So I met this bloke at a service station, and he gave me a cassette. I went home and started making notes. The next day I drove to Konk Studios in Muswell Hill and started rehearsing. I was rehearsing with the band, and we were halfway through one number when Ray Davies came in, strapped on his Les Paul Jr.

I’m thinking, “Oh my God, it’s like I’m watching Top of the Pops, except I’m actually in The Kinks. This is mad!” Then, that day or the day after, we were at Maida Vale Studios, BBC. We’d set up the sound and everything, and Johnny Walker was doing the lunchtime show from Broadcasting House and interviewing Ray via the lines—it’s all live. He says to Ray, “I understand your brother Dave isn’t well.” Ray replied, “No, he’s not well. He’s never been well,” kind of joking around. They asked, “So who have you got on guitar this afternoon?” And Ray said, “We’ve got…” and I thought, “He doesn’t know who the f*** I am!” Eventually, he said, “My granddad.”

So we play this next number, which I think was All Day and All of the Night, and there’s a kind of simple pentatonic, bluesy solo at the end. I was so angry, I pissed all over it, flying around inappropriately. At the end of it, Johnny Walker—who I’d met before when I did something on Five Live with him about adoption, and he’d also interviewed me and Danny Thompson when we did a thing called Dysrhythmia—he knew who I was. So at the end of the track, he said, “That’s Jakko on guitar there. Great solo, Jakko.” And then Ray went, “Yeah, well done, Jakko.”

I later found out that Ray and Dave notoriously hate each other’s guts; there’s terrible animosity between them. At the time, Dave was living in Los Angeles. When this live thing came up, Ray thought, “What can I do to really piss Dave off? I won’t tell him we’re doing this and we’ll get somebody else in.” On the coffee table at Konk Studios was an issue of Guitarist magazine, and in it was a 12-page feature on me as the guitarist in Level 42. Ray said, “Let’s get this bloke.” And the guy asked, “Really? Why?” Ray said, “Well, he’s obviously a very good player. He’s in Level 42 and in Guitarist magazine. I know for a fact Dave gets that magazine sent to him in Los Angeles.” So that’s why I was in the Kinks for a week.

What was it like working with Cliff Richard?

It was very surreal. My good friend Chris Porter, a very successful record producer, was producing one of Cliff’s albums. I’d just put out a solo record called The Bruised Romantic Glee Club, and there’s a track on it where I do this multi-tracked, Brian Wilson-esque backing vocal thing—lots of layers of backing vocals. Chris really liked that, and he said, “I’m doing this record with Cliff. Do you fancy doing a treatment like that?” I said, “OK.” So it was his Christmas single that year. I can’t remember which year it was. It was called 21st Century Christmas, and I did this whole Brian Wilson-esque thing. Chris said, “Oh, Cliff loves it.” And I said, “Oh, great.” Then one Sunday the phone rang, and it was Chris Porter. He said, “Are you busy this afternoon?” I said, “Well, possibly. Why?”He said, “I wonder if you could pop down to the studio because I’m here with Sir Cliff.” I thought, “He must be standing next to him—why else would he call him that?” I said, “OK.” Chris said, “He loves what you’ve done, but he’s got some ideas for the verse and wondered if you’d be up for coming down to sing them.” I said, “Alright.”

So I drove to the studio. I was living in London at the time, so it wasn’t far. In the car park was a brand-new Mercedes SLK with the registration number M-0-V-I-T. I went in, and there’s Cliff Richard. My French mother, had she still been alive, would have thought this was the most impressive thing I’d ever done—working with Cliff Richard! He said, “I’ve got this idea for the verse,” and he came up with his parts. I said, “OK.” He said, “Shall we go in and sing them together?” I said, “Yeah.” So we’re in the vocal booth, and I’m standing next to Cliff Richard, singing! It was absolutely mad. He was terribly sweet, I have to say—very generous, very friendly. It was an extraordinary thing to do.

Joining King Crimson must have been extraordinary, given that they were one of your favourite bands growing up. It must have been a special moment being on stage with Robert.

Yeah, of course. I’d been around the Crimson orbit because I’d done this thing called the Schizoid Band, which was ironically everyone in the band apart from me being in King Crimson. They were playing the older repertoire that the current band didn’t play. We’d been rehearsing, and it had been tricky—some difficult personalities and politics going on. Then one morning the phone rang, and it was Robert Fripp, my childhood hero, whom I’d never spoken to before. He said, “Jakko, it’s Robert Fripp here. How are rehearsals going?” I said, “If I’m honest, Robert, they’ve been three of the most unpleasant weeks of my life.” To which he replied, “Yes, I thought that might be the case.” So, he became this sort of personal King Crimson Samaritan, and that’s how I got to know him.

I asked him to play on my solo record, and he’d already created this other thing, so he ended up on two tracks, one of which we co-wrote. Then he asked me to come and improvise one day. We sat in the studio all day, him with this huge rack of equipment that he calls the Solar Voyager—this amazing rack of stuff and all these volume pedals. At the end of that particular session, he handed me a box, and I said, “What’s this?” He said, “That’s everything we’ve played and recorded today.” I said, “OK, what do you want me to do with it?” He said, “I’m sure you’ll think of something.” That eventually became the album A Scarcity of Miracles, where I kind of wrote songs around the improvisations. Then we got Gavin to play drums, Tony Levin to play bass, and Mel Collins. In essence, that became the basis of the next King Crimson, although that was never officially said. Then one evening in September 2013, the phone rang, and it was Robert. He said, “I’ve decided to reform King Crimson. Would you like to be the lead singer and second guitarist?” Wow. The 13-year-old in me just shat himself! [laughs] It was just mad.

When we last spoke four years ago, I don’t think you’d played shows post-pandemic with King Crimson at that point. You were one of the first British groups to tour the States.

Yeah, we were the first British band back into America post-COVID, and it was weird. What was particularly strange was how politicised the virus had become. The Republican states, on the whole, weren’t taking any precautions—they weren’t wearing masks, and there was a strong anti-vax sentiment. We started off in Florida, so we were rehearsing there and playing shows in Florida. We were quite keen to get out of there. The shows were great, and the audiences were great, but the general vibe just felt odd. We ended up in Colorado on the West Coast, and it was a strange time. For the first time, we were all on tour buses, trying to maintain this bubble. There were no aftershow get-togethers. Well, there was one in LA because the members of Tool seemed to have managed to get the backstage bar open! But other than that there was no aftershow parties.

Other than your memoir, what projects are you focusing on now?

I co-produced an album, Netherworld, with Louise Patricia Crane, which I heartily recommend and advise anyone to check out. Tony Levin is on it, Gary Husband plays drums, and Mel Collins is also featured. It’s a really interesting record, and she’s very talented. I’m now making a second solo record for Inside Out, and we’ve been recording studio versions of all the new Crimson stuff.Does that mean there’s going to be another King Crimson album? Who knows? These tracks may come out in dribs and drabs; they might be released as an album, or they may not come out at all. It’s got nothing to do with me, but at least we’ve recorded them.

Is that new material or tracks you played live?

Some of it we played live, but it’s the new material that we performed live. So it’s three or four songs that I co-wrote with Robert and some instrumental pieces that Robert wrote. Who knows?

I’ve just finished doing the Dolby Atmos mixes for the re-release of A Scarcity of Miracles, which has loads of previously unheard material on it. Because of the nature of how we made it, there are many alternate takes of different instruments. Gavin plays drums on one track where there weren’t any drums before, and there’s one track that has various overdubs as well. So it’s a significant alternate take on the whole record. I’ve just finished that, and that’s enough for the minute. More than enough.

What do you think people will take away from Who’s The Boy With The Lovely Hair? As you’ve pointed out, it covers a lot of ground.

On the one hand, it’s the story of this young kid who falls in love with music. It’s an escape and a way of making sense of his life. It’s a story about this kid who ends up working with virtually all of his childhood heroes, which is an extraordinary thing in itself. But at the same time, it’s about identity and adoption and what that means and what it does to people, and how this weird, complicated tale started to unveil itself to me. Throughout it, I keep thinking, “Oh, I know now what happened,” and then I don’t, and then something changes, and the very ground beneath your feet seems to move because it’s all changed again. I hope people will see it as an entertaining read; there are some funny anecdotes and extraordinary tales of me meeting unbelievably mad people.

Uri Geller.

Uri Geller, Jackie Charlton, the Dalai Lama.

Kate Bush.

Kate Bush, bless her. Audrey Hepburn, Roger Moore. The list is endless, and it’s all very weird how I ended up in close proximity to these people. But hopefully, it’s also a story about identity and who we are.

Further information

Who’s The Boy With The Lovely Hair? The Unlikely Memoir of Jakko M. Jakszyk order now

Jakko Jakszyk – video interview

Jakko Jakszyk – Strange Brew Podcast Part 1, Strange Brew Podcast Part 2