In a new interview, John Lodge discusses the inspiration behind his reimagining of the classic Moody Blues album, Days of Future Passed. He explores the thematic elements of the new album, now symbolising the passage of time. John also recalls the original 1967 recording sessions and how Nights in White Satin held a special surprise upon its recording reveal. John also reveals to Jason Barnard the inspiration behind his greatest songs including Isn’t Life Strange, Ride My See-Saw and Steppin’ in a Slide Zone.

You have a fantastic new version of Days of Future Passed and we’ve already heard the advance track off that, Peak Hour. I’ve read the idea for it started to come from the live dates you were doing. Is that right?

Yeah, during Covid I recorded stuff in my own studio and it was rather insular. But I thought what am I going to do when Covid’s gone and back on the road. And I started to think about the concert and I thought about all the classic Moody Blues songs and everything. While I was talking with Alan Hewitt, my keyboard player, and my daughter Emily, who manages me, we realised it was the anniversary of Days of Future Passed.

I think jointly we thought, I wonder if it’s possible to do Days of Future Passed live. We did a few live concerts with the Moody’s of Days of Future Passed, but it was really short lived. I thought, I really hope we can do that, how do I do that? And I thought I would need one big tick to do this. It was Graham Edge. I went to see Graham and said, Graham, “I’m thinking of doing Days of Future Passed on stage. Would you record your poetry for me? And you’ll always have a place on stage with me. I will also film you and you’ll be on the screen on stage with me.” He said, “John, I’d be thrilled to. I’ve never recorded my own poetry. And I would love to do it. Great. Keep the Moody Blues music alive.”

And I did. It was unfortunate Graham never saw it on stage, which is a big disappointment. But when I was performing the album, I thought, hey, this is pretty good. The reaction was really good. Emily said to me, we should really record Days of Future Passed. So we went into the studio and we recorded the album. And I’m really pleased. The 10,000 Light Year Band, they really played well. I’m really, really pleased for them as well.

Graham’s voice, including on Late Lament. It is interesting listening to your version of the album now compared to the 60s, the passage of time adds a different dimension.

It really does. I felt an incredible emotion listening to Graham saying it because it came from deep inside of him because he wrote it. When I heard it, I thought, yeah, that’s Graham. It’s Graham in all his glory. And yeah, the passage. The time thing is strange because we made Days Of Future Passed. And now I’ve made another version trying to keep the same emotion of the album, because I think it’s a very imaginative album. But the new version, I want it to be more 2023 and probably more energy, because today’s music is more energy.

It’s also an opportunity to shine light on some of the songs that maybe didn’t get as much attention as last time, including one of yours, Evening Time to Get Away. That seems to be, I don’t think neglected is the right word, but certainly with this version, you can really put it out there.

Yeah, because the first version is amalgamated with Tuesday Afternoon, it didn’t have its own place. But the song itself has its own place in the album, in everybody’s life. I was really pleased that we, the band, really nailed it musically.

Hearing Jon Davison, currently from YES, on the album, on Nights In White Satin, as well as Tuesday Afternoon, works really well. Particularly, Tuesday Afternoon, it’s a really great version of that. How did you guys come across each other?

You’re right. Tuesday Afternoon on this album, there’s something special about it. There’s a fantastic drive on this version. In 2019 I did a tour of America supporting YES. And during the concert, for their encore, YES played Imagine because Alan White was the drummer with the Plastic Ono Band. They asked me if I’d join them on stage singing Imagine. So as one of my favourite ever songs, I said yes. So I joined them on stage singing Imagine and then I said, “If I’m joining you, can Jon join me for my encore, Ride My See-Saw. And he joined me for Ride My See-Saw and he’s been in every concert I’ve done since. Not only that, my daughter and he got married as well. So he is my son-in-law, as well. But it’s great, it’s fantastic.

For the original version of Days Of Future Passed, I’ve read that you honed a lot of songs before you went into the studio, is that right?

Well, we went to a little village in Mouscron [in Belgium] to start writing our own songs and we wrote a lot of songs before Days of Future Passed. But Days of Future Passed dictated its own album, really. When we knew what we wanted to do with Days of Future Passed, we dedicated the songwriting to exactly that album. And everything we did before was just left alone, and we just recorded Days of Future Passed.

There’s a version of Nights In White Satin that you did on the David Symonds show from 1967 and it’s a very tight version. You must have been well rehearsed.

We loved playing together. It was really good. It was exciting when it was our own songs, we weren’t playing a song someone had written for us. So every part of every song we’d invented ourselves. We wanted to play each part exactly right and new and like no one else had ever played that particular part to a song before. That was exciting about Days of Future Passed, creating something that no one else ever created before. That gave a great feeling. You’re saying then about the Dave Symonds show and all that. The first time we heard Nights In White Satin was in a radio show for BBC.

We had to go into the studio and record some songs and we recorded Nights In White Satin. You have to remember, I only hear the bass part. [sings it verbally] So when we went into the control room and listened to the finish, no one, none of us, had ever heard what the actual song sounded like. We were actually taken aback. It was wow, what have we done?!

On your solo album, 10,000 Light Years Ago, there’s a track on there called, Those Days In Birmingham, which I’m fond of. So that goes back to your early years, does it?

Yeah, that goes back to school days. Eddie’s Cafe is in there where, when I was 13, 14, I used to go there every lunchtime, put a coin in the slot and listen to this rock on the jukebox playing all my favourite rock and roll songs.

And that’s where I really became hooked on bass, because I realised all the songs I was listening to on the jukebox always had a great left hand boogie piano playing. That’s Fats Domino, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis. I started to learn all these patterns on a guitar and playing on the bottom four strings of a guitar. And it was the energy that turned me on. I thought it’s the energy of rock and roll that I love.

Even on a slow song, there’s still energy. And that’s why on Nights In White Satin, I wanted to put the bass part, give it some energy. Also there’s a line about the J2. The J2 was the van we used to drive in. And it used to break down. But it was fun, being 16, 17, 18 years of age driving around the UK in this van, pulling up to gigs and writing your own name on in lipstick. As we all did.

You and Ray Thomas went way back well before the Moody’s, didn’t you?

Yeah, I met Ray when I was 15 and we became instant friends. I actually taught Ray to drive, not very good [laughs], but I did. It was great because my mum and dad and his mum and dad, because of Ray and I’s friendship, became really good friends and used to go on holidays together. Ray and I had great fun growing up together and we must have been together for like, 60 years, a long time. And yeah, it was great fun.

You mentioned it briefly earlier, Ride My See-Saw, that epitomises the driving bass. So was that written on bass?

It’s a light Fender Precision bass playing on that. It’s a bass I bought, I think it was the very first one in Birmingham. And I’d never seen one before. Jerry Lee Lewis came to Birmingham, but didn’t perform because of his marriage to a 13 year old, but there was a band on called The Treniers. They were in The Girl Can’t Help It, the movie. They were on and I saw this guy on the back playing what I thought was a Fender Stratocaster. And I realised it wasn’t, it only had four strips.

That was the very first Fender electric bass I saw. I thought that’s what I want to do. I remember going to the music shop in Birmingham called Jack Woodruff’s. On Saturday mornings all the musos were there and you pick a guitar or play something, or you learn something from another guitarist. I went there one Saturday and in the window, there’s this thing direct from the USA, Fender Precision bass. I thought that was it. I had to have that bass. I remember going home and telling my father, come on, you’ve got to help me.

We went up and bought that bass. So I’ve recorded nearly every Moody Blues song with that bass. And I’ve recorded the new album with that bass. It plays differently. I don’t know what it is, but it’s something magic in that bass. Whether it’s because of all the touring, it’s done over the years, but it plays differently.

You made so many amazing albums, after Days of Future Passed. Taking, for example, To Our Children’s Children’s Children and your wonderful song, Candle Of Life, you managed to bridge, moving away a little bit from the orchestration and being able to create a more band, studio sound.

Yeah, we were always experimenting and it was strange because after In Search Of The Lost Chord, we went to America for the first time and we saw America. It’s really difficult to explain today because America then was different to America today in our minds, because the cars were bigger, everything was bigger. The jukeboxes were everywhere, and played music everywhere and the radio station, you could play music all day long and it was a different place. We were with other bands, Canned Heat were big friends of ours, we toured with them a lot and Jefferson Airplane. I think it changed our way of doing things. We were really working well together as a band and then we started to think, well when we get into the studio let’s keep it tight as a band and record really as a band.

Isn’t Life Strange is another one of your pivotal tracks. Do you think that’s a theme of the lyrics of your music? Many of them present your feelings about what it’s like to be alive and going through life.

I think so. Yeah, you know, when I was 15, 16, when I started writing, it was always like, I love her, she loves me, blah, blah, blah. And then when I really started getting to my serious writing, I suppose. There was sort of a homespun philosophy in the writing. I really like to have layers in the writing of my songs, and put them to the right piece of music that I think goes with that song. The catch line, I’m just a singer in a rock and roll band, just sums it all up at the end of the day.

You’ve got Isn’t life Strange with a bit of, as you say, homespun philosophy, but you’ve got the humility with I’m Just A Singer In A Rock And Roll Band.

Yeah, that’s all I have. That’s all I have.

The Moody Blues coming back in the late 70s, it was a different sound at times. You’d moved on a bit to a synthesiser and then again, one of the key Moody’s tracks Steppin’ In A Slide Zone. What was the inspiration for that song?

When we recorded what became the Octave album, I was never too sure it was the right time to make the album. Also we were recording in America and it was the first album we were going to record outside of the UK. While we were recording so many things went wrong, not with the band as people, but we were starting recording at the Record Plant. And the Record Plant burned out while we were recording. That was one. I broke my arm. Another one. I recorded after the album with a broken arm and it set with my bass there and said, set it like this so it could still play. And I did that. It was awkward getting in and out of cars, I tell you! Arm up the air.

Then private lives in the band between guys and wives, that started to fall apart. We lost our producer during the making of the album, he disappeared. So it really left it to Justin and myself, to continue making the album and producing it. Then we went up to Indigo Ranch in Malibu. And while we were up there, there were the worst floods ever. The mountain slid down the hill and we were stuck up in the mountain in the studio. For days we couldn’t get out.

And Steppin’ In the Slide Zone seemed to conjure up everything to me that was wrong. Or fighting the tide, probably. Yeah, fighting the tide. But it’s a great album. It ended up being a really nice album. It was really hard work. But it was a great learning experience for us. Because after that, we went and recorded Long Distance Voyager, and that just flew out of the record stores. But Octave, I really like it. I enjoy listening to that album.

You mention Long Distance Voyager flying out of the record stores. One of the reasons for that was Gemini Dream. Part of that was inspired by a wish to get the band back on the road.

Absolutely. I wanted to write the song saying, let’s get back on the road. Be who we want, because I’m a musician. I like to play. I like to perform. We had a band which could really perform, and I really wanted to get back on the road. So it’s long time, no see. Short time for you and me. I had that in my brain. And actually the first incarnation of it, roughly, it was called Touring America, not Gemini Dream. But that was like the engine that started us on that road, Long Distance Voyager.

I wanted to close by asking you about a song that you re-recorded before the pandemic on your very best of album. We were talking earlier about certain tracks from Days of Future Passed that were a bit neglected, was it that Street Cafe needed a bit of a wider airing?

Street Cafe was a happy song. Kenney Jones joined me on the drums for that and Kenney’s on the video playing with balloons and all that, it was great. It was really trying to be a happy song. It was relating to exactly the same as anywhere, it’s so the music played from a street cafe, right? That could have been in London. He could have been them or he could have been me as a 13 year old at school going in to listen to the jukebox. It was all those things, all those emotions in there.

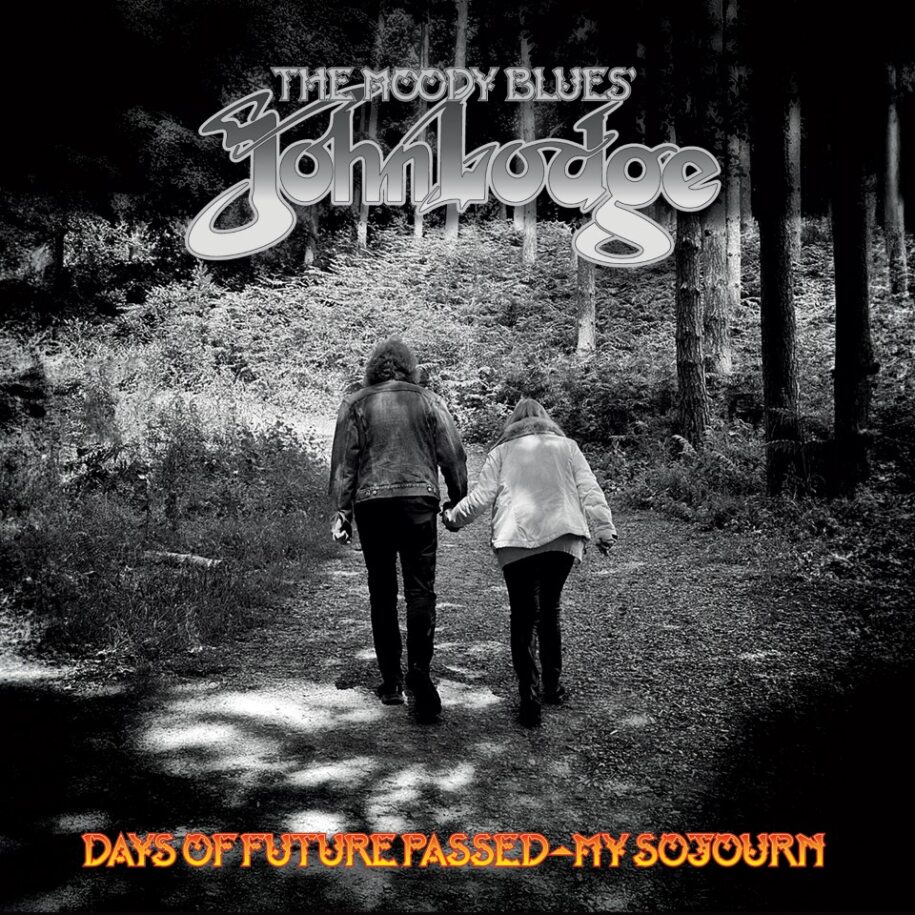

One final question is the cover of Days of Future Passed – My Sojourn. We were talking about the resonance and the passage of time and that’s you and your wife on the cover isn’t it?

Yeah, the guy who normally does all my artwork, he was doing the artwork for the album. And he was going along really, really excited about the album. And it was my wife’s birthday. And in Cobham here, there’s a place called Painshill Park. It’s like an 18th century manor, fairy grotto and all that. I said to my wife, we should go walk through there. My son came along with his wife. We had a fantastic afternoon, just wandering through the woods. There’s a vineyard there and it’s brilliant. And my daughter-in-law took a photograph. She sent it to me and I looked at it. I thought that is exactly Days Of Future Passed – My Sojourn. That is exactly what I’m trying to say with the new version. And I didn’t question it. That was it. I told everybody, forget what you’re all doing. This is the sleeve. And yeah, I’m really pleased with the sleeve. It’s really calm. I like that. It’s a passage of time with no time going through. If that makes sense.

Well, you couldn’t have summed that up any better, John. It’s been a pleasure and privilege to talk to you. And a brilliant way of recapturing the magic of one of the greatest albums of all time by one of the greatest bands. So thank you very much.

Thank you very much, Jason. Good luck to you and thank you for the interview. Take care.

Further information

Audio podcast version of this interview coming soon.

Days of Future Passed -My Sojourn – stream and CD available now, vinyl November 24:

USA https://shop.johnlodge.com UK https://burningshed.com/store/john-lodge_store

Interviews also available: Ray Thomas, Alan White podcast