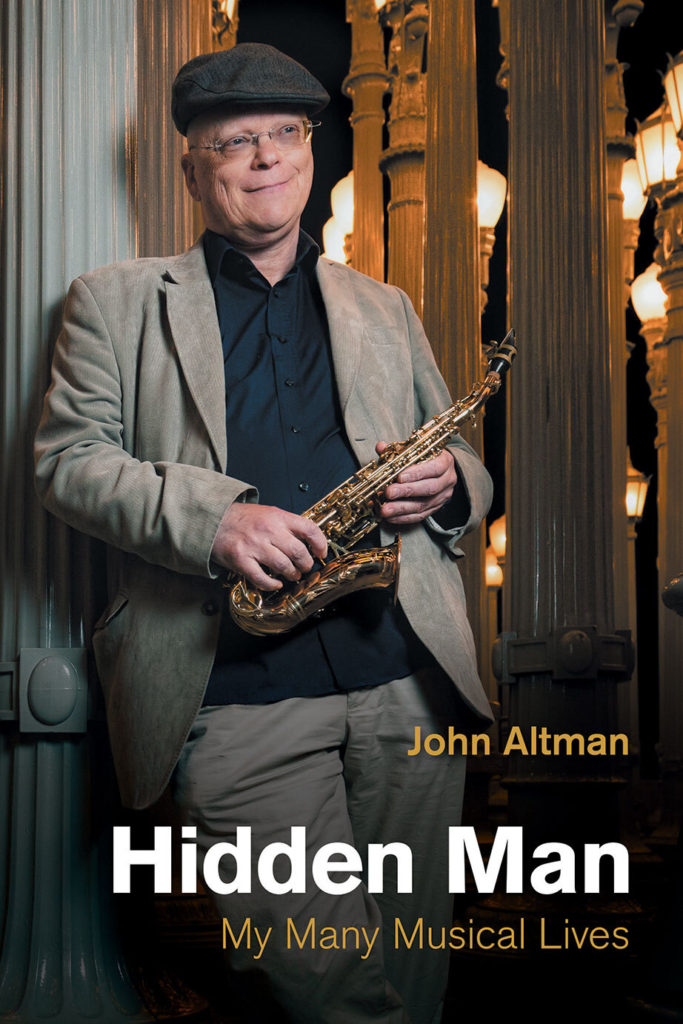

You will have heard John Altman’s music but may not recognise his name. His new memoir Hidden Man: My Many Musical Lives corrects this wrong by highlighting his work as composer, arranger, orchestrator and saxophonist for the last half century.

In this transcript of his 2021 Strange Brew Podcast interview with Jason Barnard, John covers many of those moments that captured popular conciousness. From ‘Always Look on the Bright Side of Life’ from Life of Brian, the tank chase through St. Petersburg in the James Bond movie Goldeneye and working with The Rutles, Van Morrison, George Michael, Rod Stewart and Bjork, John talks about his many musical lives.

This is what I have to say about John Altman: Think about it: Without exaggeration, it can be assumed that half the music of the 20th century wouldn’t exist without John’s contribution. The other half is rubbish. (Hans Zimmer)

Hello John

Hi there. What a pleasure it is to talk to you.

Likewise.

I’m a big fan.

No! No!

Not at all. I really enjoy them. They’re great.

Well, you’ve heard an episode?

You’ve talked to a lot of my compadres and people I came up with like Kim Rew (Katrina and The Waves) and Chaz Jankel (The Blockheads) and it’s always nice to hear them.

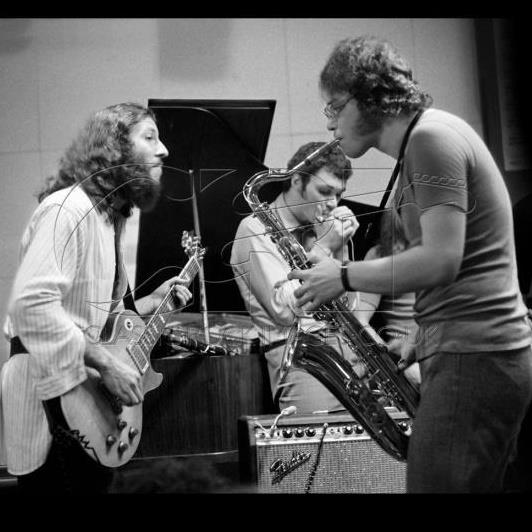

We featured Dave Kelly just to ease us in gently in terms of some of the work that you were featured on and that’s relatively early in terms of the work that you’ve recorded, certainly in relation to the rock/folk/blues idiom. Maybe it’s worth just starting out in terms of how I’ve heard you were on that 60’s music scene at a relatively early age and got to know many of the artists involved there.

Yes. I was very lucky. I started playing sax when I was 13, having had piano lessons from the ages of seven till eleven, immediately joined a band and gigged the night after I bought my saxophone which must have been horrendous – absolutely horrible! Luckily, like a lot of people of that age, I moved through many local bands. There weren’t many sax players on that scene so I was always in demand. From my early schoolboy bands from the age of 13, it was unbelievable how many went on to have big careers in the business. My first group included Martyn Adelman, who formed Syn that became Yes (Chris Squire used to hang out with us), then the next group included Stuart Epps, who worked a lot with Jimmy Page and Elton John, and Clive Franks, who was also with Elton John for many years. The next group I went into included Kim Rew (whom you’ve interviewed) the composer of ‘Walking On Sunshine’ and a member of the Soft Boys and Katrina and the Waves. After that I joined up with Chaz Jankel who wrote all the Blockheads hits and ‘Ai No Corrida’, Pete Van Hooke of Mike and the Mechanics, Rick Parnell of Spinal Tap, and Jon Rose the music publisher. These were all just local bands, so by the time I was 18/19, had left school and before I went to university, I was already getting on the scene and as you know, in those days, most of the bands like Fleetwood Mac, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and the Jimi Hendrix Experience were playing in the upstairs rooms of pubs. They weren’t in stadiums. You would pop down to your local pub and there they were, and I got to know them.

Because I went to university and I was on a full grant, I never needed to become fully professional, which helped me because I could go and sit in anywhere. I added flute, which you heard on the Dave Kelly track, and clarinet. So, I started showing up at gigs and because I knew the people, I would then be playing with Peter Green, Nick Drake, John Martyn, Bridget St John, Kevin Ayers. I formed this sort of network, as it were, of incredible people with whom I knew I could just drop in and play with. When I went off to university I was recording. I did my first record which was a Brunning Sunflower Band album with various people from Fleetwood Mac and the Kellys (Peter Green is on it too) and then Peter and I started playing together when he left Fleetwood Mac which was astonishing (I wish it had been recorded but it wasn’t) and that’s how I got to that level at that young age. And then things fell into my lap – Muddy Waters wound up playing at my 21st birthday party – ridiculous. You can’t make it up. It’s impossible.

There’s no greater education really than being on that that music scene and, just to mention Dave Kelly, he was obviously a very renowned blues artist although the first track there was more in the folk genre and Dave was one of those artists that was on the fringes of the sort of Fleetwood Mac area as well as you were.

Yeah we all knew each other and we all played with each other and what was quite interesting was all the people on that circuit – that was the circuit that the Rolling Stones had been on and they had literally catapulted from playing at Studio 51 on Sundays to stadiums in America within weeks. It wasn’t months and months and years and years it was literally “oh we’re going to pluck you out of here and then you go there”. I even went to Led Zeppelin’s first gig, which was in a room upstairs in a pub. My ears still hurt but the scene was very fluid and so many people were so creative and people have often asked me “wasn’t it amazing to play with Nick Drake?” Nick was amazing, but so was John Martyn and so were Dave Kelly, Andy Fernbach and Bridget St John – they were all fantastic. I never thought “oh Nick is special”. In fact, I’ve been writing my book “Hidden Man’ and I found the diary entry where I was trying to convince him not to give up playing live gigs. I spent an hour with him and John Martyn trying to talk Nick out of stopping playing. It was a week before he did. So, it’s quite extraordinary really to be on the fringes of all that exciting music, and also being a part of it.

That’s going to be one hell of a book isn’t it, John?

Well, it’s going to be interesting because I followed it through as it were right up to today … Well, I mean, to have gone from Muddy Waters and Nick Drake through to Prince and Amy Winehouse and John Legend. There’s no one else who has done that – I’m the only person who’s done that and survived. I think I’ve survived.

No absolutely and you mentioned Kevin Ayers there, our next track being ‘Guru Banana’ but again you look at that session – Ollie Halsall, obviously Kevin there, yourself and Elton John as well on that session as well so again a real testament to the scene that was around and musicians just all cross-germinating.

Oh totally. Elton was a fan of Nick Drake; he was a fan of Kevin’s which is why Kevin signed to John Reid, I think. Kevin was offered the gig with Hendrix before Noel Redding and turned it down and the great thing about Kevin and Peter (Green) was, it sounds crazy, but you really never knew what the gig was going to be. You didn’t know what songs were going to be played. You didn’t know – there wasn’t a set list. You just got on stage, they started something, so you joined in and then they started something else, and you joined in with that. And I loved that. Maybe it was because part of me thrived on that improvisational outlook – I didn’t join a band per se and say “right, you’re backing Arthur Conley and you’ve got to play sweet soul music every night” and never deviate from the record. It was experimentation and it was always something new and that was a great thing. I loved playing with Kevin. I think the last time I played with him was actually 2000 in LA, so I had nearly 40 years playing with him really, which I loved, and it was never any different from start to finish.

And a bit of a tie-in relation to our next track in terms of Ollie Halsall who played on that Kevin Ayers material, the Rutles ‘Cheese and Onions’ but maybe it’s worth just talking about how you got involved with Neil Innes because it’s a bit of a build-up in terms of the Rutles and there is a bit of a theme that goes on, as we’ll cover in the podcast, as well.

Ollie and I were very, very close friends and I don’t just mean musically. I would go around there virtually every night and play board games and when he was away, I’d still pop around and play Movie Maker with his wife. It sounds mad but we were that close, and Ollie always involved me in things that he was doing musically, let’s say, either directly or indirectly. He’d just joined Jon Hiseman’s band Tempest and they were playing at the Marquee and he said “oh come down” so I drove him down to the gig and we were hanging out at the bar with Neil Innes. Neil and I had met briefly when he was in the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band but not intimately or anything. Anyway, we hit it off. Ollie, on the way home, said “oh, I’m recording with Monty Python tomorrow with Neil. Do you want to come and play?” Of course, I was a fanatical Monty Python fan. Great. Fantastic. So, I rolled up to the studio, in I went, we got on really well, and I was accepted into the Python’s inner circle as the music guy and that’s where I stayed! I did everything Neil did thereafter for years and years. All the Innes Book of Records, all the Secret Policeman’s Balls, every Neil Innes record, live shows, Rutles. It really spiralled from that evening.

‘Cheese and Onions’ was actually a song that was originally in his Book of Records wasn’t it, so it was pre the film.

No. It was in Rutland Weekend Television.

Oh gosh. Right. Yeah, of course. So it was after Eric Idle was involved.

That’s right. Yeah, yeah, yeah. What happened with the Rutles – I know you spoke to John Halsey and he probably told you the same story, but theyd done a little spoof on The Beatles for Rutland Weekend Television – a five minute segment, and when Eric went over to do Saturday Night Live in New York (Saturday Night as it was called then) he showed that sequence, because there was a running gag that they’d offered three thousand dollars for The Beatles to get back together. The response was so huge that Lorne Michaels said well, let’s make a special. So, Eric rang Neil and said have you got 20 more songs we can do? The amazing thing about The Rutles of course was that The Beatles had only broken up seven or eight years earlier so I could book people who played on Beatles’ sessions, George Harrison was in the studio – it was like making a Beatles thing but not really The Beatles. And George was marvellous and it’s almost beggars belief that The Rutles was made basically at the same time as Life of Brian and The Innes Book of Records. They all came in a great wodge and meanwhile I was playing with Van Morrison on the road. “Help. Somebody free my brain from all this mania”. Great time.

Yeah, and when you listen to The Rutles, the arrangements of some of those tracks and there’s the strings aping kind of that psychedelic period as you can tell on ‘Cheese and Onions’ and ‘Piggy In The Middle’ and all that material. Were you kind of like emulating a bit of George Martin there?

Totally. Totally. Not only that but because I knew who was playing on all these things, I could ring the musicians and get them. So, incredibly, the cellists had been on a lot of The Beatles records – they would go (mimics the glissando cello sound from ‘I Am The Walrus’) “that’s what we did” and as soon as I heard that I went “that’s it”, that’s what we’ve got to have”. All the vibratos of the string players are the same and when we did ‘Double Back Alley’ I rang David Mason who played piccolo trumpet on Penny Lane and he wasn’t actually free but he recommended Cliff Haines who did a great job – I parodied the solo on Penny Lane. The whole thing was really parodies of Beatle arrangements. If George Martin used a full orchestra, I used a solo piano going plonk and it worked really well. They all loved it. George Martin loved it, apparently. George Harrison loved it. I mean a lovely conversation I learnt about three days ago was George Harrison said to Neil “Ollie Halsall’s guitar solo on ‘Love Life’ is a send up of my guitar playing, isn’t it?” and Neil said “Yeah” and George went “Oh, okay”. I thought that was wonderful. This indignant comment “He’s sending me up, isn’t he?” “Yeah.” “All right.”

I meant to ask. You mentioned that final piano note in ‘Cheese and Onions’ – was that your idea or Neil’s?

Me. That was me.

It just adds. It’s one thing having the song which is Beatlesque but it’s those touches on top that just make it double.

On ‘Love Life’, the original demo that Neil gave me had ‘Liberty Bell’, the Monty Python theme, at the beginning. Basically, all the years I worked with Neil, he never told me what I should write or anything like that. I always just gave him what I thought was best so we worked really well together and I decided that ‘Liberty Bell’ was just too silly, it just didn’t fit so I said “well, let’s do ‘John Brown’s Body’ because at the beginning of ‘All You Need Is Love’ they’ve got the Marseillaise. I wrote ‘John Brown’s Body’ for the intro and that’s what they went with. I was throwing in touches, probably without realizing it, that stuck.

Wow. That’s fantastic to know about that final note – doink.

Oh yeah, yeah. I think originally Neil thought it was going to be a big chord like the end of ‘A Day In The Life’ but I thought “no, we’ve got to make it funny” because it’s been so serious up till that point and then the animation was absolutely brilliant. I loved the film. I thought it was wonderful. I didn’t have any involvement in it at all, but I was knocked out.

Absolutely. And then we’ve got to discuss Monty Python of course and what many people won’t know was your extensive involvement in ‘Look on The Bright Side Of Life’ because I think I understand that when it came to you it was more a bit of an Eric Idle sketch of a song rather than what we what we finally heard?

It was Eric playing guitar and singing it, not even in the voice that he uses in the film. It was just basically “here’s a song I’ve written” and the other guys freely admit that they weren’t that impressed. “Oh, okay, he’s written a song. Oh, it’s all right” Basically they didn’t have an ending for the film. He’s going to escape somehow, well he’s going to do this, well he’s not going to get free. How do we finish it? And Eric just said “well let’s have this song” and suddenly because we decided it should be like a Busby Berkeley type thing, suddenly it was dancing on crosses and all that, which was great. But I have to say, Michael, with whom I still talk a lot, said “I didn’t think it was very good, it was all right” and Terry Jones absolutely loathed it. So, it’s interesting how history has sort of turned.

It’s that one moment isn’t it from the film that has got into the national consciousness.

I wish I’d known. I did another session that afternoon and I have no idea what it was. None. I went on to Air Studios from Chappell – did the whistling along with the Fred Tomlinson singers and scooted out of the door. I’d no idea what was going on. If I’d known I’d have milked it and just been “Oh right, this is great. Got to stay with this” but it never happened.

I’ve read that Terry Gilliam called you the hidden man and that’s the title of your forthcoming book, Hidden Man, as we’ve already discussed in terms of some of these roles in terms of music, people don’t know the role that you’ve played on all this.

No. Well. I guess it works two ways doesn’t it? It’s if you want a normal life out of the limelight you sit back and let everybody else take the glory and then when you burst forth and go “Hello. Here I am” everyone says “Well, who the hell are you? Who wants to know about you?” and, to be involved, as you said, in so many things. I don’t feel that I’m tangential in the sense “Oh, I met Madonna coming out of a restaurant once” or something like that but I can say “Well, I arranged George Michael’s biggest hit record” or “I brought Rod Stewart’s career back on track” or “I got Pierce Brosnan his movie break” and it’s all true. That’s the frightening thing but nobody will know that because I chose not to be in the limelight.

Why does John Altman choose to be the Hidden Man? What is he ashamed of? I always thought he was tremendously talented. A great musician and an all-round nice guy. Perhaps I was wrong. (Terry Gilliam)

Yeah. Yeah. And next to an artist who you mentioned earlier and obviously we’ve got to cover it and you worked extensively with him especially in the live space as Van Morrison, we’ve got Moondance from a live version from his Wavelength tour. It was much of the 70s that you worked with Van, wasn’t it?

Well. It was interesting. I met him in about ’74 when he broke up the Caledonia Soul Orchestra and he came to live in London and really got to know him through Pete Van Hooke who, of course, was drummer with him for years, and we became very close friends and he always said to me “We should do something musically. One day we’ll do something”. The first thing we did apart from jamming in the front room was in ’77. Van had a band with Dr John, Mo Foster, Pete Van Hooke and Mick Ronson. It was a very interesting combination and they played at a London venue for a Granada Television recording, and at half time Van said “Right – jam session” so I got on sax, Brian Auger came up, Roger Chapman sang backing vocals, Bobby Tench and Ray Russell on guitars and we jammed, and it was fantastic. The TV producer said “Okay, we’ve got to stop now.” “No. No. No. We want to go on. We want to go on” and really after that Van said to me “Right. I want to form a band like this band. A larger one and I want you to rewrite everything that I do” and that’s what I did. I rewrote all his charts and all he asked me was “Where do I come in?” It wasn’t “Well, this one should sound like this”. I was faithful to what had gone before and most of the rhythm arrangements were already established but I also wanted to tart up a few that I thought were maybe a bit dated or with this line-up we need to be a bit more jazzy – something like that, and we put the band together for the Wavelength tour. I was supposed to play on the record, but Van never showed up in the studio the day I got there, so that went out the window, and later I went back to do the Into The Music tour in Europe which was also great fun and then, because I’d started doing Python and writing a lot for the BBC, I decided “well you know what. I think my future’s actually in writing rather than in touring” and I stepped away and that that was the last live tour I really ever did – in’79 which is a long time ago. I disappeared into the studios really for the next – god knows how long.

And you mentioned the studio, of course, which just leads us perfectly on to George Michael and ‘Kissing A Fool’ and I don’t know if it’s a similar situation with the Eric Idle ‘Look on The Bright Side Of Life’ but when George Michael presented you that track was it again more stripped back and then you kind of build it up?

It was interesting. He rang me at home “George Michael here” and you think “Yeah, yeah, okay. Who’s having a laugh?” and it was. And he said to me “You’re the only person who can do this with me.” “Oh. Oh. Okay.” and he continued “I love the Alison Moyet record That Ole Devil Called Love” and I said to him “Well I didn’t produce that. I was the arranger.” He said, “Yeah, but you we know you did all the hard work. The producer is nothing…” “Oh, that’s very nice”, so he sent me a demo. Basically, the song was about three quarters finished. It wasn’t finished. It was piano guitar and bass. There were no drums, no horns and no ending! So, I just put the whole thing together and put the horn section together and, when we did it, he actually said at one point “You inspired me to become a musician.” “Oh. What?” I knew that his father owned the restaurant where we used to go when we rehearsed. And this is with Chaz Jankel and Pete Van Hooke, and he would sit outside and listen to our rehearsals and that’s what decided him. He wanted to become musical, which is amazing. We got on well and I was very flattered to find out later that when he toured, he played our track because he said to his band, who had to mime “You’re not going to be able to play it like these guys” so that that was nice.

And that song has got a real classic jazz feel and obviously you’re steeped into that music so, is that kind of you shaping that track into the feel of it?

Well, that’s the feel he wanted so, yes. I mean it’s six of one, half dozen of the other. I did it that way because I could tell that’s how he wanted it to be. I rang my great friend Steve Sidwell, who did a load of work with George, after the first day and said “Look. I don’t know whether he likes what we’re doing, whether he hates it. It’s all ‘let’s do another one. Let’s go on. Let’s do this, do that’” and Steve said “Well, you’re going back aren’t you?” I said “Yeah, I’m going back tomorrow or the day after”. He said “Well, then, he likes it. You’d know soon enough if he didn’t because he’d say, ‘It’s not happening, there’s the door, bye-bye’”. But that was very much what he wanted, and, for example I’d used, for the first time, Ian Thomas on drums and I knew that George would absolutely love his drumming so I booked him on the session. It was his first recording session and, of course, George loved him and used him thereafter. That was his choice, his drumming choice, so that was good. He was great to work with. Again, it’s stood the test of time – to me it’s amazing that almost all the records I did are still listened to. The artists are still big, and people still buy the records or talk about them as their favourite record and, selfishly, I have to think that maybe I had something to do with it. Perhaps I gave them something that they wouldn’t have had otherwise. Rod, Tina Turner, Prefab Sprout. Who knows?!?

When you hear ‘Kissing A Fool’, in a way it could have been released at any time in the last hundred years. It just does not – it cannot date. It’s always current.

Yeah. I had this discussion with Mark Ronson with whom I worked. Just about the fact that so many things that people think are current suddenly become unhip and not current, whereas things that just go right the way through, they’re not of their moment but they’re of every moment and that to me was what I always felt. Certainly, hearing a lot of 80s records with Syn drums and cheesy synths you tend to go ‘oh god’… Really it’s as bad as 80s haircuts. It will all come back I’m sure but I the thing is, if you’re never in fashion, you’re never going to go out of fashion. So that was always my mantra. Don’t do anything too of that moment because it won’t be of that moment anymore.

Absolutely and next to Rod Stewart and ‘Downtown Train’, released in the late 80s here but again has a classic sound but a bigger, more broad production than the Tom Waits original. Can you tell me about the circumstances of getting involved with Rod and then how that track developed?

Yeah. I think it’s all down to Trevor Horn who was producing him and, to be fair, Rod’s career wasn’t exactly at its zenith at the time and Trevor suggested ‘Downtown Train’. Rod had never heard of it, didn’t know the song, didn’t know much about it. But we went ahead and started working on it and as soon as he heard it Rod went “Oh, oh I’ve got to get into shape” and apparently, after I’d done my orchestral chart, he went into the studio and the key was too low. It was set when his voice was out of shape. All my arrangement was done in the key of G and Trevor, somehow, before auto-tune and all the magic dust that you could sprinkle, pushed the key up without speeding up the track. They took it up to B♭ which is quite a long way and I heard it in the Virgin Megastore in LA, and I thought “Well this sounds familiar, but it doesn’t” and I realized it was ‘Downtown Train’ and I went up to the DJ – they had an in-house DJ then – and said “Would you mind playing that again? It’s my arrangement.” and I listened to it and the strings and the cor anglais had a really ethereal otherworldly sound. All the vibratos were wrong because it had been modified. What seemed like a hideous sort of error actually turned out to make the record what it was. There are all kinds of things – Jeff Beck’s guitar in the middle is amazing and Trevor’s production, as usual in those days, was second to none. I did a lot of work with Trevor at that time and all the things I did with him just sound great now. Simple Minds and Tina Turner, Rod. They all sound marvellous.

So, just as an example, working with Trevor. How much of a brief would he give you when he presented a track and asked you to do an arrangement?

Interestingly, he really let me just get on with it the way I felt it, and this is before intensive demoing of stuff so, very luckily, on most of the movies and all the records I did I never took in a demo. I just went in with a bit of music under my arm and went “Right. Okay. Strings. Boomph.” and if Trevor suddenly said “Oh. You know what. Keep the strings quiet for the first chorus but bring them in the second one” or “maybe, in this chorus, we should just have semibreves behind the voice” you would change things on the session. I know he had a reputation for switching things around but with me I never heard a collaboration we had done and thought “Oh. Do you know what? I wrote something there and it’s gone”. It was always in there somewhere, so I was very lucky, and I worked with Trevor probably from… I think I started on Simple Minds on Street Fighting Years and went right through – I’m trying to think of the last thing I did with him. It was probably Tina Turner, and then after that he asked me to do Seal’s first album, but I was in LA doing a movie so that all went out of the window and basically by the mid 90s I had stopped writing for records completely because films had taken over and I think that pigeonholing mentality that people have was, “Oh. He’s doing a movie. He’s not gonna want to do an arrangement.” so I sort of vanished off that arranging scene that I’d spent so much time on.

But a theme of this discussion is about how things that you’ve done or much of it hasn’t dated because it never goes in or out of fashion and the next track is the perfect case in point – Bjork’s ‘It’s So Quiet’. Wow. So, again, how did you get involved in arranging that track? Such a startling song which now goes down as a moment in music history, really.

It does, doesn’t it? I wish she was a bit fonder of it than she seems to be because she tried to disown it, which I don’t really understand. Apparently, a fan had sent a recording of it to her (it was a B-side of a Betty Hutton record in the 50s) and said “You should do this” and she said “Yeah, yeah. That’s great.” So Isobel Griffiths, who’s now probably the orchestral booker in England for every big movie but, at the time, was just starting out and had been my advertising producer called me and said “Can you do a big band chart for Bjork?” I said “Yeah, sure.” so they sent me a copy of the Betty Hutton record and it was great. Obviously quality-wise it sounded dated. It sounded like it was a 40s track and I just polished it up and gave it a gloss. I’d never met Bjork and the first time I met her was actually in the studio and as you know, recording sessions with session players are booked from 10 in the morning till one. Three hours. By quarter to one she hadn’t shown up, so you can imagine the stages of panic that I was going through because it was basically vocal driven. We couldn’t record a click track and say “Right. Sing to that.” because it got slower, it got faster. She arrived in the studio at ten to one with a big smile and said, “What’s happening?” I said “Well. What’s happening is we lose everyone in ten minutes” and she said “Oh. I thought they were here all day.” and I said “I’m sorry, they’re not. They all have to go.” and she said “Right. We’d better get on with it and do it.” and, four and a half minutes later, we finished the record. What you hear is first take – live – her singing and the band playing. Unbelievable. When people ask me “How long did it take to record ‘It’s So Quiet’?” I say “Well. How long is the record? That’s how long it took”.

I guess that’s how records used to be recorded often – live, one take.

Yeah, yeah. I anticipated we would need three or four takes to make it really work and (I don’t even remember this) Ralph Salmins, who played drums on it, says we did do a second take. I don’t remember that, but it obviously wasn’t as good as the first take. That first take was absolutely perfect and when you also think that it was in Angel Studio One (sadly no longer functioning) and she was in the vocal booth diagonally to my left, the brass and saxes were on my right, the bass, drums, guitar were behind me and the piano was in a booth to my right. So, none of the people in the room could hear her. Only the rhythm section had her in the headphones. The front line heard the rhythm section, and everybody was following my conducting – on the ice! So basically, if I went wrong, everything went wrong. If she makes a mistake, everything stops and it didn’t. It just (snaps his fingers) went down first take. Done. Brilliant. And it sounds like it’s got that excitement of a first take. I was very impressed, and I hung out with her quite a lot while she made post because I would go in when Deodato was there and hang out with him and sit in the studio and I would just look in and see how they were getting on – it was fun. When we did Top of the Pops, they couldn’t find her. She was in the car park lying on the ground listening to the earth. That’s different. She certainly marched to her own drummer I think that’s the thing.

Brilliant.

Great fun to work with.

And now we get to about 10 years ago and Evan Rachel Wood ‘I’d Have You Any Time’ which was from the Chimes of Freedom album, The Songs of Bob Dylan. Now that was an Amnesty International record, wasn’t it?

Yes.

And Amnesty. There’s quite a number of connections about this track. There’s the George Harrison connection and there’s the Amnesty connection through the Secret Policeman’s Ball as well, so maybe it’s worth touching on a bit of that. Maybe the Secret Policeman’s Ball stuff?

Well. I did the first two Secret Policeman’s Balls as musical director and the first one, apart from Neil Innes’ song where we wheeled on the big band to surprise everyone, was pretty much solo artists. Donovan, Pete Townshend, who did a duet with John Williams. Victoria Wood did a song. Dame Edna Everage did a song. But Martin Lewis, who produced the show, decided that for the second one we should have a band and have more music. So, he asked me to put a band together and, between us, we would recruit “big names” to perform and it came about interestingly because he got Sting through Sting’s acting agent. Not through the music side. Phil Collins heard about it and said, “I want to be involved”. Martin rang Eric Clapton and he said, “Can I bring a friend?” who was Jeff Beck. Then Bob Geldof and Midge Ure came on board. This is before Live Aid, so this gave them the idea. And then there were Sheena Easton and Donovan, and heaven only knows who else and I put together a really good session band behind them. Chaz Jankel was on it, Mark Isham was on trumpet. My cousin Simon Phillips was on drums. It was a great band and we did the finale ‘I Shall Be Released’ – this germinated the whole idea, not only of Live Aid but the subsequent Amnesty concerts where Bruce Springsteen and U2 and the Police and everybody came on board and toured.

Martin and I stayed in touch, and he called me and said “We’re doing (A Tribute To) The Songs of Bob Dylan but there’s a song that Bob Dylan wrote with George Harrison. (‘I’d Have You Anytime’). Would you like to do it and who would you like to play on it?” I heard the song and we both agreed “ let’s do it in a 40s style” and I said I would like to have Patrice Rushen, a great solo artist (on piano), Clayton Cameron, who was Sammy Davis’s and Tony Bennett’s drummer, Ed Livingston (bass) who then was playing with Herbie Hancock, and Lawrence Juber (guitar) who was in Wings. You know, to make that connection with George. Then we got Tom Scott who was not only in George Harrison’s band but was a really close friend of George’s and then I had my George connection because George mixed ‘Bright Side of Life’ and was involved with The Rutles, and he and I were very matey. So, we recorded the track and Martin had already said “ I put on a show a couple of years ago and the actress Evan Rachel Wood sang and she was tremendous, let’s get her to sing” and I think she knocked this out of the park. He rang her and she immediately agreed to do it. She’d never done anything like that before and it came out fantastically. It was great because, having not really been working on records for a long time, I was suddenly doing a record again.

And arranging a Dylan/Harrison track into a sort of more jazz 40s feel. Was there something about that song that that lent itself to that style?

Yes. I thought that the chord structure of the song immediately suggested that it would take that because the first two chords were slightly jazzy, so I thought, well, I’ll extend that and make that into a thing for the whole song. And it came out really well, I think. It was great to work with Patrice and Tom and all the others, and Evan. For me it was like old times to to go back in and work on somebody else’s record.

And then to close, John. It would be remiss without touching on some of your soundtrack work and what we have next is one of the most famous scenes in James Bond and, in a way, film history is the very famous tank chase from GoldenEye. Now, much of that soundtrack has got a bit more of a contemporary feel but I understand for this particular part of the film there was a request that it was a bit more of a conventional Bond feel which, when we hear the final track, we definitely hear and then you were called in.

Yeah. I was on the film from the start. What happened was, not only was I writing a lot of movie scores myself, but I was also arranging and conducting scores for other people at the same time. I was very lucky – I got to work with Elmer Bernstein, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Mark Isham, as we mentioned, Jule Styne, and I started working a lot with Éric Serra, the French composer. We had done a movie called Léon which, in America, was entitled The Professional, a wonderful film with Gary Oldman and Jean Reno. The Bond producers were relaunching the franchise and they said “we want a new James Bond sound”, and they hired Éric and, by default, me. I went along as his orchestrator and from the very early days it became quite obvious that that wasn’t really what they wanted at all – plus Éric was used to working with Luc Besson who idolized him. They’d been to school together. Everything Éric wrote Luc (would) put in his film. He didn’t even show up at the sessions. Suddenly you’ve got a director, an editor and a dubbing editor and three producers and they’re all making suggestions and Éric was responding “No. I don’t want to hear any of your suggestions. You don’t know anything about music. Leave me alone. I do what I do”. So basically they got to the stage where they were dubbing the film and they decided there was no traditional James Bond moment in the whole film and the tank chase had to be a traditional James Bond moment so they rang me and said “Would I write that sequence?” and I went into Pinewood on the Friday and I said “Look I’m not doing it unless Éric says it’s okay for me to do it because he brought me on to the film”, and they said “Well, we’re going to do it anyway”. The director rang Éric and he said “Yeah. John can do it. Go ahead.”

So, I literally went into Pinewood and saw the whole eight-minute sequence. I said “You don’t need to tell me what to do. I know exactly what you want.” I took it away, wrote on Saturday. I orchestrated it on Sunday, had it copied on Monday, recorded on Tuesday, dubbed on Wednesday and the film came out on the Friday! So, within a week it was created but the thing was I’d grown up watching James Bond movies. I knew what they wanted and, luckily, I was able to deliver it but the interesting thing about the Bond sequences is that Monty Norman’s theme contractually had to be included in the movie, and bizarrely Monty sang with my jazz group, so he was very pleased that I’d got his theme into the film or there might well have been another lawsuit going on. I don’t know. The sequence starts with the tank bursting through the prison wall and then it demolishes Saint Petersburg, goes through a truck, has a statue land on top of it. It’s one absurdity on top of another and the thing about scoring an action sequence is you have to plot an arc to your score. You can’t start with a huge climax and then where do you go? You’ve got to go somewhere, so you’ve got to start somewhere, build, build, build, build, build, build so the trick really was to start reasonably big, include something of my own, go big again but bigger than the first time, then go again bigger the second time, then grow even bigger. It is like climbing a mountain musically but great fun to do and as you say it’s one of the three sequences that I’ve done in movies that everybody knows. Whether they know I did them or not, I don’t know, but you’ve got Life of Brian, (Bright Side of Life), you’ve got this Bond sequence and you’ve got the ship sinking in Titanic with the band playing on deck, which is me again. It’s not a bad achievement, I think.

Not bad. Not bad.

Not bad for a start.

I feel like we’ve only scraped the surface here John and, as I mentioned earlier, there is certainly a book ready for February publication by Equinox Books entitled Hidden Man.

It’s all finished now, comes out in February and it touches on basically all these events plus fun encounters with the likes of Freddie Mercury, David Bowie, George Michael, Prince and Stevie Wonder etc. Just people I’ve interacted with along the way. Also, my days playing in Hot Chocolate which was something we didn’t even go anywhere near which was great fun, being in a chart-topping band.

Great band.

One of the best live bands I’ve ever seen, and I was part of it.

Well. What can I say John? We’ve only scraped the surface but hopefully that means that people can dig in even more into your career and see that you are no longer the hidden man anymore.

That’s fantastic.Thanks very much for having me.

No, it’s a pleasure and honour John.

Thank you. My pleasure.

Further information

Hidden Man: My Many Musical Lives by John Altman is published by Equinox on 15 February 2022 and is available to pre-order now.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Nigel Davis for transcribing this interview.