Skip to content

By Nick Warburton

Originally from Milwaukee, keyboard player Jim Peterman first met his future band leader Steve Miller at the University of Wisconsin in Madison during 1964. He talks to Nick Warburton about his time with The Steve Miller Band and recording the landmark albums, Children of The Future and Sailor.

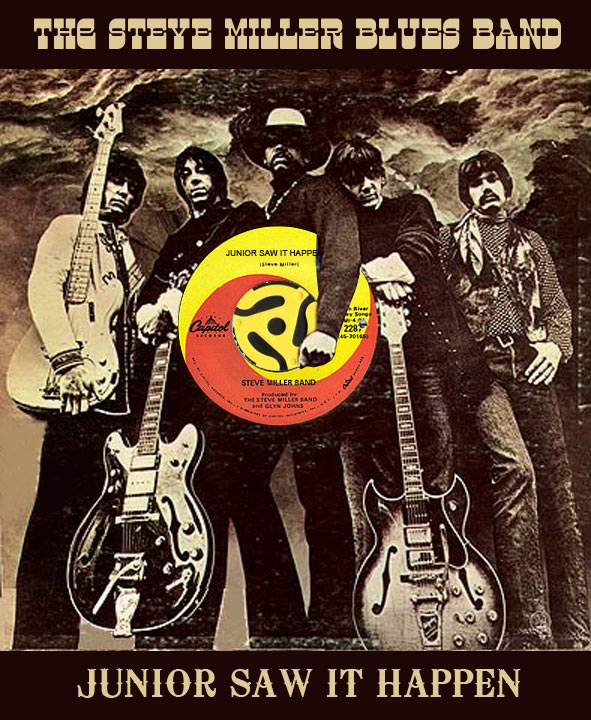

The Steve Miller Band 1968 – (clockwise from bottom left) Lonnie Turner, Tim Davis, Jim Peterman, Boz Scaggs and Steve Miller

Q) Am I right that one of the first bands you played with was Tim Davis & The Chordaires, featuring future Steve Miller Band members, drummer Tim Davis and rhythm guitarist James ‘Curly’ Cooke?

No, Tim and I lived together in college for a few years but didn’t play in the same band. I was the lead singer for the original Playboys, a high school band in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. In the summer of our first year of college we signed with an agency and they required that you had to play an instrument. I messed around with the piano some and a friend from church taught me enough to get started as a singer/player. In college, I played in one or two bands pretty regularly, not the best for grades but a lot of fun.

The Playboys (top row, Jim Peterman on left, Bill Patterson – drums, Rick Kludt – lead guitar, left of drum – Don Valley – bass, Ricky Bruhn – rhythm guitar)

In 1965, I had a band called The New Blues with a guitar player named Denny Geyer and he really started me listening and playing to the blues. He, Tim Davis and Curly Cooke were The Chordaires in college. In The New Blues, we had a harmonica player named Jimmy Liban from Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Then we added a fella called Jim Marcotte on bass and that became The AB Skhy Band. Actually, a fella called Ken Adamany was playing organ in this AB Skhy Band and I was just a singer.

Adamany was an agent and would put shows together. He booked the show in Madison, Wisconsin that Otis Redding was coming to when his plane went down in Madison and died. Adamany went on to become the manager of Cheap Trick. The AB Skhy Band came out to San Francisco shortly after I went out to California to join The Steve Miller Blues Band.

Q) How did you get called up into The Steve Miller Blues Band?

Curly, Tim and a bass player called Dick Personett from Jamesville, Wisconsin went out to San Francisco to join up with Steve in late 1966. Personett left after a short bit and went back to the Midwest. He was replaced by Lonnie Turner, who was about 18 years old at that time and lived in Berkeley. I was still in college at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. We all knew each other, so when they decided that they wanted to add a keyboard for the sound, they called me and offered to fly me out in February 1967 and play for the weekend and see how we all felt about it. That was a way exciting weekend in my life! We just played at the house and we jammed for about 10 hours.

[I went back to Madison] and they called in a month. When they did call back, they said, ‘Yeah, we’d love to have you and we think it’s going to sound good but you really need to come now!’ I had to sort that one out. I called back and said, ‘I’m three months away from graduating after five years in school, if you can wait for me, I’d appreciate it’ and they decided to wait thank goodness. (Ed: Future Steve Miller Band keyboard player Ben Sidran flew out to San Francisco with Peterman).

The Steve Miller Band, 1968

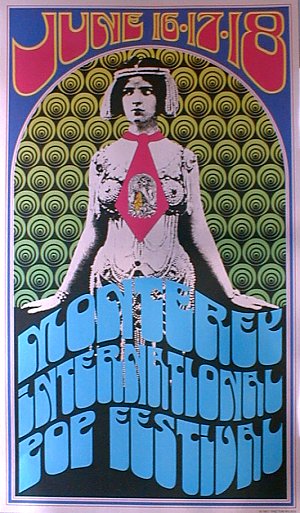

Q) So you must have arrived late May/early June 1967 – just in time for the Monterey International Pop Festival?

Yeah, it scared the shit out of me. I wasn’t a real confident player and to be kind of plopped into the middle of that was just incredible. It was scary. We had played at a couple of local bars [before] – the New Orleans House in Berkeley and the Matrix on Fillmore Street. We were practising in the basement; we had one of the five-storey Victorian houses in San Francisco [on Pierce Street]. To see Otis Redding was probably the biggest thrill in my life. I always liked his stuff. I was an R&B lover more than anything.

Monterey International Pop Festival Poster

Q) Did you hang around with other musicians at the festival?

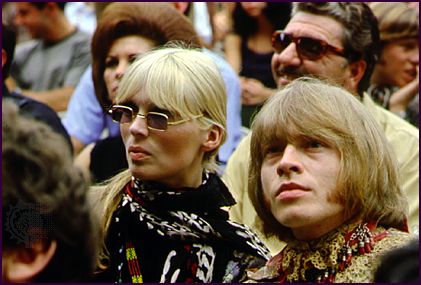

It depended on who it was. Brian Jones was flitting around the place for the weekend and he was approachable. Most of the bands were. The San Francisco bands – we all kind of knew each other. There was a really strong community at the time that I moved out there. You’d see The Grateful Dead on the street. Stanley Owsley had this Monterey Purple LSD just for the weekend. People were in a wonderful frame of mind. Ravi Shankar was probably as big a thing as Otis Redding that afternoon. That was one of the biggest treats of my life to experience that whole thing.

Nico and Brian Jones at Monterey

Q) A lot of people don’t know that The Steve Miller Blues Band played the Monterey International Pop Festival. Was it pretty much blues material you did?

The band then had a really strong blues sound and it was very formative. The group was still developing and with the San Francisco thing going on, the influence of the San Francisco vibe I would say and eastern music, Ravi Shankar, it was a really unique blues sound. We were still called The Steve Miller Blues Band at that time. Monterey was probably our first big exposure to a larger crowd and it was through that that the record companies started getting interested.

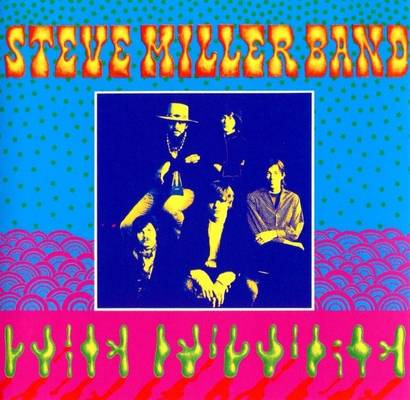

The first album [Children of The Future] was probably the closest to that original [blues] sound but it had already taken a bit of a turn towards a pop direction. We were rehearsing for the first record in this little studio called Trident that The Kingston Trio used in downtown San Francisco. It was a basement place. We got that as a rehearsal space for a month or so. Steve was already working with pre-recorded sound tapes and electronic music in October/November ’67 and was listening to Stockhausen, John Cage and The Beatles. The rest of the band wasn’t really in to it. It just really caught a hold of Steve. His direction then, right before we were getting ready to get that first album’s material together, the change in sound and style that we had, it was developing into the sound that was on the first record – Children of The Future.

Steve Miller Band, Children of The Future, Capitol, 1968

It was getting clear to me that Steve just had this sound that he was hearing in his head that wasn’t the blues band that we had all joined to be part of. I think it put tension between all of us and Steve because it was a change from what we all felt strong about. The blues band was a real ass-kicking band. I don’t think it would ever have been as strong as his pop sound. More and more he wanted to tell me or whoever what part to play and it just pissed me off. It made me feel kind of like, ‘I can’t hear what is a good part to play myself’. I could see that it was inevitable. It was all part of what he was doing. If you listen to Steve’s music, you can see that it’s very sorted out. Boz [Scaggs], Tim and I were going to do a trio [in late 1968] actually then Tim got cold feet. I think he thought it was more secure to stay with Steve.

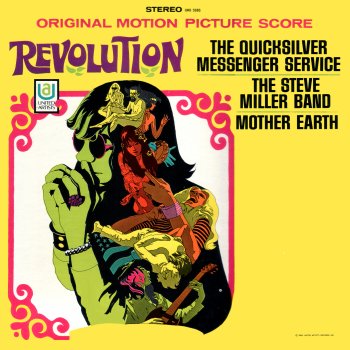

Q) Going back to the summer of ‘67 when Boz’s predecessor James ‘Curly’ Cooke was in the band, you ended up recording some songs for the soundtrack to the movie, Revolution.

I think there were two songs that were placed on that record and they would be really the only recordings of what we sounded like as the blues band. I mean the nature of it and the feel of it. Curly was just a strong part of that early sound of the group. As a rhythm player he was really awfully creative. He had a lot of stuff that he was hearing in his head and was a really strong force. We did a lot of shuffle tunes. He had some interesting little loop things that he would do. Tim’s timing was not real consistent. Tim was a colourful drummer but he didn’t practise a lot and Curly would play and just about stare at Tim right in the face and just be pumping this fucking rhythm guitar and Tim couldn’t do anything but stay in line. It was great. They were in The Chordaires together so I think Curly was used to that position. Lonnie [Turner] was just this kid [and was a] finger style folk and bluegrass picker that played bass guitar. I think he was 18 at the time and was just a laid back, sweet guy. He ended up being one of my closest friends. The rhythm section of that band was just smoking. Steve didn’t have to worry about a thing.

Revolution Soundtrack LP, United Artists, 1968

Q) How come Curly left?

He and Steve fought worse than Boz and Steve ever did. They just had screaming matches. Curly was getting upset and he just couldn’t take it with Steve. I remember when he left it was a sad day.

Q) Then you got Boz Scaggs in the band. He’d known Steve since the early 1960s and played in his University of Wisconsin band, The Ardells.

He didn’t really have any contact with us at that point. He was in Sweden and for a time he was just doing a street musician type thing for tips. When Curly left we just did it as a four-piece for a while but we could see that it wasn’t going to have the strength. I wasn’t that strong as a keyboard player and the sound between the two guitars was really part of what we had going on, so Steve contacted Boz and we paid his way back over here to give it a try. His playing was strong and he had some really cool things to offer plus himself for one.

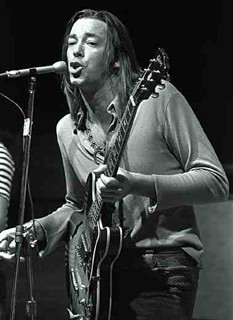

Boz Scaggs

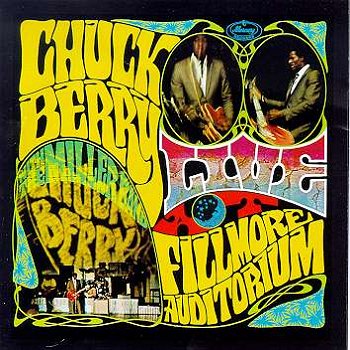

Q) When Curly was with The Steve Miller Blues Band, you recorded an album with Chuck Berry. What was he like to work with?

It was a thrill. The duck-walk thing was his trademark and a gimmick and all. But to see the magnetism; I mean he wasn’t showy per say but the attraction he had with an audience was really something. He was nice with an audience. He did a thing in the middle of his act where he recited this melodramatic soppy old poem, probably from the 1930s, and it described this house and all of these different things he would have in this house. He played it sparsely on this guitar – and this is Johnny B Goode. You could hear a pin drop. He had that place in the palm of hand. In the middle of one of the tunes, he was doing a solo and he kind of walked over to me and he said, ‘What song are we playing?’ I thought he was pulling my leg and then he started singing a different song to the one he had started. I thought that was pretty novel. If you listen to Curly’s playing on that Chuck Berry record, you can hear the strength he had as a rhythm player. It was great.

Chuck Berry, Live at Fillmore Auditorium LP, Mercury Records, 1967

Q) Is it true that Steve Miller made it a condition of signing to Capitol Records that you would record in London?

You know, I am not sure. The way that I remember it was Harvey Kornspan, our manager, I think he got ‘X’ number of dollars written in for expenses for recording. I am sure we indicated that we were interested in doing that [recording in London]. It’s probably splitting hairs but I don’t know if it was a condition or that we got a lot of money and we could go to London to record if we wanted to. I know that it was said at that point that we had the best contract with Capitol Records I think, second to The Beatles. I don’t know if that is true but Harvey was a shrewd man and did very well by us.

Q) I read somewhere that all of the band, except Steve Miller, were caught up in the drug bust that took place at your London residency (Ed: 3 South Eaton Place, near Sloane Square tube), which I gather was about February 1968, so presumably you must have completed the Children of The Future album before that happened?

We weren’t done [on the album] but we were close to done. They [The authorities] said we could finish the work we had there [but] they cancelled our work visa. We had gigs lined up in England, which we were to do after we were done with the record and they said we couldn’t do those. I think it must have been EMI’s lawyers that went to bat for us in that situation. We were deported with a condition that we could finish the task at hand.

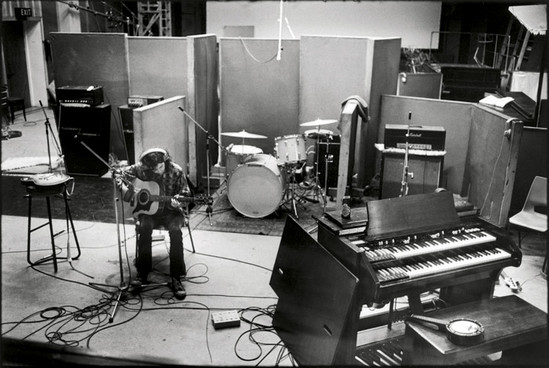

Q) How long did you spend recording that first album at Olympic Studios in Barnes?

I think it was at least six weeks. It was a long time and there would be a day or two when we weren’t working. It hit a comfortable pace. If we had to, and wanted to, we probably could have done it in four weeks.

Olympic Studios, Barnes (Ed: this is Jimmy Page on a separate session in 1969)

Q) Did you get to see any live music while you were staying in London?

We went to a place – I can’t remember what it was called, the Cellar maybe – it was a large basement place. It wasn’t far from Covent Garden (Ed: Possibly Middle Earth). We saw Stevie Winwood with a trio [Traffic] and that was great. But there wasn’t much other going out to clubs. I guess we were recording a lot into the evening. My brother was living in Aix-En-Provence that year and he came over for a week to visit. My wife – we’d just gotten married maybe a month before I’d left for London – she [also] came over to spend the rest of the time there.

Q) Can you remember any of the live gigs that were lined up in England but then cancelled?

No, I don’t. Harvey took care of that stuff and we were ready for anything. But we did have a show in Paris that we did maybe a week and half after we were done with the record. We could each do what we wanted with ‘X’ number of dollars. Tim and I and my wife decided to go to Paris and visit this girl that Tim had picked up on the boat over to London. Her family had a place near Cannes on the Riviera. The four of us took off for her place and spent I think five days down there. She took us on this beautiful tour of Italy one day.

Steve Miller came over for two days and joined up with us. We couldn’t say ‘No’ that he wanted to come over but it was already getting to be that thing where he wasn’t the guy in the group that you picked to hang out with. You loved playing music with him at that point but it just wasn’t fun somehow. He was so uptight and off the wall in a funny way. I think he’s gotten a lot looser. We were hanging out in the Riviera and then we came back for this show called Bouton Rouge (Red Button) in Paris. It was a kind of a Hullabaloo thing from the States you know – go-go dancers. That was one of the things that Harvey had lined up after we were done with the record. We did that show and then we flew back to the States.

Q) You must have played in New York on the way back?

We played in New York on the way [to London]. I can’t remember if we played New York on the way back or not but we played the Boston Tea Party and some place in Philadelphia maybe. It was like an old gymnasium and was all painted black.

Steve Miller Band, Boston Tea Party Poster

The second part of Nick Warburton’s revealing interview with Jim Peterman covering the Children of the Future sessions, his departure from the Steve Miller band and his current projects can be found here:

http://thestrangebrew.co.uk/articles/jim-peterman-and-the-steve-miller-band-pt2