By Jason Barnard

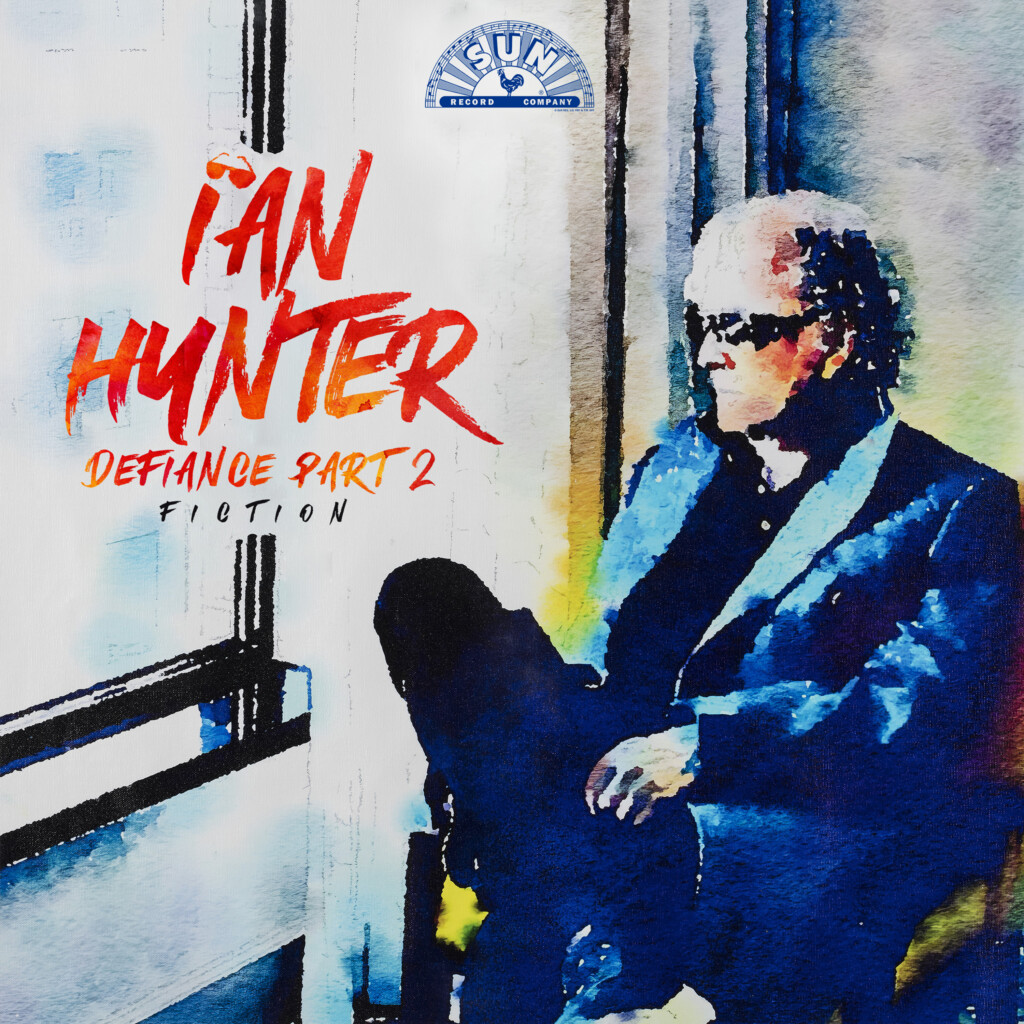

Ian Hunter spills the beans on new album ‘Defiance Part 2: Fiction‘ and on his past in Mott the Hoople. Ian also takes us back to his days honing his craft in Hamburg, the early years of Mott, his relationship with David Bowie, Mick Ronson and key points of his solo story. (The podcast version of this interview will be released in April.)

‘Defiance Part Two’ has got more of a political element. Is that something that marks it out differently to ‘Part One’?

Yeah. The first one was when COVID had set in, people weren’t that happy. So I tried to avoid those kind of subjects as much as I could. However, it caught up with me. And this is a bit more politically scientific.

You’ve got Joe Elliott and Brian May on ‘Precious’.

Yeah, and Taylor Hawkins.

You and Brian May go way back to the 1970s, because Queen supported Mott, didn’t they?

Mott were the only band they ever supported. They pretty much shot up right from there. They opened for us in England and then they opened for us in the States. Then Brian got hepatitis, actually, so they had to cancel halfway through the American tour.

The next thing we knew, they were headliners. They were great people. It couldn’t happen to nicer people. I said to Brian for this track, “Fancy putting a bit of guitar on it?” and back it comes, with all these guitar tracks on it and the bass as well.

That combination of Brian and Joe Elliott and yourself, I’ve seen some great footage of all three of you doing ‘All The Way From Memphis’. So you’ve all played together before.

Oh yeah, if ever I’m in London, Joe’s always around, and Brian sometimes, in Shepherd’s Bush or something like that. I remember the Astoria. That was a great gig. I remember Brian got up on that one and Joe.

Queen were a great band to tour with. You get bored when you’re on tours with your own band. With those guys, it was like we were all as one. It was lovely. Fred was outrageous, which made your day. And we had Ariel Bender and he takes everything up 20%, so it was a lot of fun. One of the main reasons I always wanted to be in rock and roll was camaraderie, the fun of it.

Brian said that you were mentors because they watched Mott live and that helped them when they headlined.

They’d be standing outside the stage, checking it out. They hadn’t really figured out what they were gonna do as a stage show. They figured out what was happening with their music and everything, but they were just watching to see how one conducted oneself. I kinda learned off Jerry Lee Lewis.

There’s a difference between trying to please people and running the show. I think that’s what Fred was looking for. There’s a little amount, there’s a bit of arrogance involved, and it goes down well. At least it did in those days.

How did you pull together the guys that you collaborated with on both parts of Defiance? Did you know them all, or were they friends of friends?

I knew a few of them from odd meetings, just like an odd bump into kind of situation. I don’t know any of them properly. Waddy [Wachtel] I’d met before. The guys from Tom Petty I’d met before, way back, somewhere down the road.

But I hadn’t met a lot of them. Billy Gibbons I’d met but I’d never met Slash, I’d met Taylor briefly. There’s a guy called Ross Halfin who’s a photographer. He would ring me and say, Slash, or somebody, they’re up for it if you want to do it.

They had the home studios and COVID was on, nobody was out. So they had time on their hands and they weren’t doing anything. So that’s how the idea was formed. It wasn’t formed by me, it was formed by Ross Halfin. With a little help from Mike Kobayashi who runs my business and things.

How did you divide the material between the two albums?

Part One came together pretty quick. That naturally solved it. I had more difficulty with this one. This one’s denser and it’s more even. Part One, it kind of told you where a specific track would tell you where it wanted to go, it helped. This one was difficult. I’m still not sure it’s in the right sequence.

There’s a number of songs there that seem to comment on the world. For example, ‘Fiction’, is that about misinformation?

It’s pretty self explanatory. It’s always awkward in interviews, they ask you to explain what you’ve already explained. But you really don’t want to make it worse than it already is, because the press does that anyway. This is what you see, it’s just my interpretation of it.

A few of the songs also seem to refer to the divide between people, which seems to be increasing over time. Where people are talking to each other separately in their own bubble and then throwing things across.

Yes. I think we’re going the wrong way. I think AI, the internet, all this stuff is causing more trouble than it’s worth. There’s good points and there’s bad points. But everybody’s got an opinion now. Some people shouldn’t have one! Probably I’m one of them! I don’t know.

There’s also ‘What Would I Do Without You’, which has got Lucinda Williams on it. How did that duet come together?

She came to a gig in Nashville and we got on, and her husband’s a really nice guy and he’s a bit of a fan of mine. So we asked her if she’d be interested and it’s great. With [Robin] Zander and the Robinson brothers, they’ll sing the full thing a couple of times, and then they’ll just say, if you don’t want bits of it, don’t use it.

They’re very nice that way. It’s not like you have to have me on the song and all that kind of stuff. It’s not like that. They’re like, take what you want, leave what you want, it’s fine. Lucinda was like that – just use what you want.

You mentioned the sequencing of ‘Defiance Part 2’. But you do end with the song ‘Hope’, so finishes off positively.

That was a no brainer. That was always going to be the last track.

There’s a song on ‘Defiance Part 1’, which is called ‘I Hate Hate’. That seems to be from a similar lineage.

Yeah. I like that lyric a lot, because it’s simple and it’s direct. From a lyricist’s point of view, that’s what you’re looking for. You’re looking for simplicity and directness. Lennon was a master at it.

On that album is also ‘This Is What I’m Here For’. So was that about you looking back towards your early years?

Yeah, self-explanatory. Waddy did a great job on it. I thought that was definitely a last track, because that is what I’m here for. When I was like 16, 17, 18, when Fats Domino first started and Elvis, I think they started in 54 and then soon to be followed by Chuck Berry and all the greats, Jerry Lee, Sam Cooke, Buddy Holly.

That’s when they get you. We got Joe Elliott when he was 15. That seems to be the age where you get stuck for life with something. That sort of paves the path to some people, musicians, something they hear and, you know, that’s it. Off you go.

There’s also ‘Bed of Roses’ from that album. That echoes your time playing at the Star Club, doesn’t it?

Yeah, I was there in the mid to late sixties. I think it closed in 1969. Ringo was there earlier on. They were there before. But, it was a fantastic club. It was a fantastic time. Tony Sheridan was still there. I was his gopher! [laughs] Go and get this, go and get that. Very authoritative guy. But he was the original singer with the Beatles.

Roy Young also had been asked to join The Beatles. He was at the Star Club when I was there. And Roy was the king of Hamburg, and turned the Beatles down because the Star Club offered him a Cadillac to stay. He would play with anybody, organ, piano, and sing. He’d even play with anybody, but they’d asked him to join the Beatles. He turned them down to stay in Hamburg with his Cadillac. I asked him in later years, “How did that feel?”, He said, “I get up every morning, I bang my face against the wall once and I’m fine!”.

It’s well known that Hamburg knocked The Beatles into shape. Did it have that effect with you playing so much in a short period?

Yeah, it was great. I was a bass player and was playing with a guy called Freddie Fingers Lee. You played every night. In England, you played St. Mary’s Village Hall on a Saturday night and that was about it. You might play a working man’s club on a Monday, eight quid. But in Germany, you sometimes played seven nights a week. I played for 13 hours, one in the afternoon till two in the morning. That only happened once. But the drummer couldn’t get off his kit. His ass was cemented to the seat. 50 minutes, 10 minutes off, 50 minutes, 10 minutes off. So you learned.

In the 60s, you were also writing songs, weren’t you?

I was writing them and Freddy Fingers Lee said to me, “You’re writing decent songs, but don’t ever sing them.” But nature took its course.

How did you end up in Mott? You were in The Shriekers, you’d written some songs, how was that connection made?

A guy called Miller Anderson, who later on became a pretty well known blues player in Europe and England. He was living in the next street to me and we used to go to auditions together. We were working in a factory. I got a phone call from a guy called Bill Farley at Regent Sound. Regent Sound was kind of like Sun Records, a little 4-track in London. We’d gone down there and done sessions for various people who’d go in there, and they weren’t very good. It was like five quid for a session.

He would sometimes have bands in there auditioning for new members. Bill rang me one night and said, “This band’s down here, and I think you might fit with them. They’d tried everybody else.” I lived in the Archway, it was a bit of a schlep to the West End, Denmark Street. But the buses were… I was there in about 30 minutes, which was amazing. They weren’t overly impressed, but it was like, he’ll do till something better comes along.

How did you pull together the material for those first few albums? There seemed to be quite a few covers and Mick Ralphs and Pete Overend Watts were writing some songs.

Pete and Mick were supposed to be the writers. They hired me as a piano player. But then Guy [Stevens] liked me as a singer because he said I sounded like Dylan. Not being a proper singer, I figured out, people like Dylan were getting it over in their own way. So that was the course I decided. I used Dylan as a stepping stone, if you like, for the first, couple of years.

Eerybody moaned at me, so I had to stop. By that time, you start finding your own thing, the way you can get yourself across. The band weren’t too convinced at first. Then by the time the band didn’t want me in the band, then Guy wanted me in the band. It was very delicate, the first nine months. Meanwhile, we’re making these records. We don’t know what we were doing.

Guy was like, “Do this, do that”. It was pretty frantic. Then we started touring, and the touring got kind of popular. And we were selling everywhere in the end, like the Newcastle City Halls, Birmingham City Halls. But we didn’t have any record success, and you’d have to have that to sustain. People aren’t going to continue to turn up if you don’t chart, at least in those days. And that’s where David came into the scene.

There were some great songs on those Island albums like ‘Waterlow’ and ‘Rock And Roll Queen’. Do you think it was that you were still trying to still find your own voice and feeling things out?

Yeah, we were in the learning process. Mick Ralphs was a Steve Stills and West Coast fan. I’m at the Little Richards side and he was at the West Coast side of things. We were trying to figure all that out. And the band was trying to figure it out with us. We liked the slower stuff. We like the Waterlows. We liked all that stuff on Wildlife.

But then the stage show was crazy. It wasn’t adding up, it wasn’t making much sense. It needed something to meet in the middle. It did to a degree on the last Mott album before Bowie. That was Guy Stevens producing, that was pretty much Martin because it was frantic.

Was that ‘Brain Capers’?

Yeah, it was a pretty crazy album and all kinds of things were going down, but we let loose. That was somewhat near to what we were like live. But we’d just go in there and tear a place up. Guy and us didn’t have any idea of what was going on behind the controls.

Glyn Johns was the engineer. We just went in and Guy screamed and shouted “You’re better than anybody” and all this kind of stuff. We’d have to wait for about an hour while he went through these whole diatribes and then he’d unleash you and off we went.

You mentioned David Bowie coming on the scene. How did he hear that you guys were on the verge of splitting up?

We had split up in Switzerland. We came back and Pete now was looking for a bass job. He found out that David was looking for a bass player. Then David apparently had already got one or he didn’t want one. But he didn’t want Mott to split up anyway.

He said, “You can’t do that.” So Pete rang me and said, “Look, this bloke wants us to go down and listen to this record. He sent us one first that we didn’t particularly like and then the second one was Dudes. He played us that in Regent Street, sitting on the floor in an office, in DeFries’ office. That was it, ‘All The Young Dudes’.

What was it that made it a great single and superior to David’s version? Was it arranged differently?

Well, he’d done it already. The story goes that he hadn’t done it, he just wrote it overnight and gave it to us. That’s not true. He’d already done it. He did it in the key of C, which is a lower key.

We went and we took it up to D to make it a little more powerful. He hadn’t done the wrap, which I did over the hooks to make the hooks a little more interesting. He hadn’t got that amazing Mick Ralphs intro. He hadn’t got Phally, who was great on the organ.

But he had the knowledge of what he’d done and what he didn’t want to do again. It all came together in a couple of nights. We did that and ‘One Of The Boys’ at Olympic, Barnes. And It was quite magical, quick, great song.

You released a string of singles that matched the greatness of ‘All the Young Dudes’. Was it a challenge that you didn’t have to be reliant on David’s songs?

The press they could be pretty… now it was going to be that we were David’s band. He offered us, I forget. I know there was ‘Suffragette City’ in it at one point either before or after. But we only ever did ‘Dudes’ because we wanted to be Mott The Hoople. Then Mick and I spent a frantic nine months trying to find a single to follow the single, because this is what you do. I came up with a song called ‘Honaloochie Boogie’ and I think it got to about 11, something like that. So it was okay. Then we had ‘Memphis’, ‘Roll Away The Stone’, ‘Golden Age’. They were all our songs. But we still lost people because they’d liked the original crazy version of Mott, now we were more sophisticated apparently.

Do you think the experience of recording ‘All The Young Dudes’ shifted the sound of Mott? Did you respond to what was going on around you, whether it was David or other bands like T-Rex?

We had no experience with Guy. That was just a gang fight in a studio. We didn’t know what you could use. We didn’t know what you could do behind the board.

We didn’t understand how you could enhance things. We went to Air Studios when we did the Mott album, which was the one after ‘All The Young Dudes’. We happened to bump into Bill Price, who was an amazing engineer. We started actually using the studio instead of sort of waltzing in there and just jamming.

What was it like working with Roy Thomas Baker?

Oh, Roy’s lovely. I mean, a great sense of humour. I think he, I think his great contribution with Queen was his sense of humour, because they were so intense when they would do stuff. He’s an extremely funny guy. Like David, he mixed thin, because in those days, transistor radios were the thing. That’s how everybody listened.

Mott The Hoople seemed to have a great connection with your fans, working class kids.

I wasn’t young, I was 29 when I joined Mott. I’ve been in factories for years and it was not much fun, but, lyrically, it was great. I had fodder, it was not like I came straight out of school. What are you going to sing about, your girlfriend? Well, that’s only one track. I’ve been around, I’ve had like 40 jobs, and with the jobs came the lyrics.

When you had a song that you wrote like ‘Roll Away the Stone’, how did it work arranging that with the group? Some of the songs were quite ornate and had backing singers?

I don’t know. I didn’t really have that much to do with that end of things. Mick Ralphs was brilliant. We all dug in there, you know, but I would say Mick Ralphs would, and Bill Price, the engineer. Then we’d all pile in. Faders went one way only. [laughs] Bill would get extremely angry with us. He always wanted the bass to be the loudest instrument. All the mistakes you make. I remember Roxy were in Air One.

We were in Air Two. And Bryan Ferry and Eno came down to our studio. We were doing something and we were still looking for a producer. They were like, “Why? This sounds great.” It never actually occurred to us not to have a producer until that point. But what was going on sounded good, and Bill Price was great, and we just figured, leave it at that. I guess Bryan and Eno did us a favour there.

Absolutely. What led to Mick Ronson joining the group?

We were pretty exhausted, and Bowie had split, so Mick was on his own, Mick was living in a flat behind the Albert Hall. I heard he was around, and we’d done a couple of years with Luther and Luther had been fantastic live. But we hadn’t really gotten much out of him in the studio. Mick Rock, the photographer, said, “Why don’t you go and see Ronno”, so I popped round to Ronno’s and it was all over in one night.

DeFries was in America, so he was talking to DeFries because at that time Mick was still in his solo career. Meanwhile, he’s left me in a room while he’s on the phone, and there’s a little drum machine in that room. It wasn’t even a drum machine. It was before drums. It was one of those things that waltz, quick step, you know. I was fiddling with the thing. I was fiddling and I got this groove. Well, actually what I did was I pushed every button down.

There were about seven buttons. I pushed them all down and out came this rhythm. I started writing ‘Once Bitten Twice Shy’ while I’m waiting for him to get off the phone with Tony DeFries. At 5 a.m I’m pretty much… This is going well with ‘Once Bitten’. He comes in and he goes, “Yeah, I’m going to join.” So he was in. He was in not for very long because he didn’t get on with the other guys in the band.

But we did stuff like ‘Saturday Gigs’, which he more or less arranged, produced. It’s a shame, because it was great what he was doing, but it was short lived.

There’s a song where Mick contributes vocals, ‘When The Daylight Comes’ from your album, ‘You’re Never Alone With A Schizophrenic’. Did you encourage him to sing? He was quite shy at times, wasn’t he?

He used to tell me off, he used to tell me what to do. I mean, there were a few Micks but Mick in the studio was bossy. We were in the Power Station and I was talking to Meat Loaf and Bruce.

And he came out and he goes, “Are you gonna do this vocal” [Ian responses to Mick] “In a minute!” Mick replies “Because if you don’t do this vocal, I’m doing it.” I said, “Well do it.” So he did! [laughs] It sounded great, so it was just fine.

How did you pull together the material that you did with Mick for Ellen Foley? Because there’s songs on there like ‘Don’t Let Go’ that are amongst some of your best.

I must have been on a roll. We had ‘Schizophrenic’. Everything was going really well at the time. We had great management. We had a guy called Steve Popovich. And it was chart big over here.

We were just in a good frame of mind. And Steve Popovich also had Ellen Foley, she’d been touring with Meatloaf. Amazing voice, incredible voice. Would I do, Foley? Mick was hard up, as usual. So I thought I’ll do it with Mick, Mick’s better at it than I am. So me and Mick did Ellen or Ethel, as I used to call her!

There’s a song of yours off ‘All American Alien Boy’ called ‘You Nearly Did Me In’ that’s got Roger Taylor, Brian May and Freddie Mercury. How did they get involved with singing backing on that?

My wife Trudi was on a plane coming back from England. I was in Electric Lady doing ‘All American Alien Boy’. And they were on the same plane as my wife. And they asked what was I up to? Because they knew Trudi.

And she said, “He’s down Electric Lady making a record.” So they got off the plane and came straight down. John didn’t come. The other three came. I didn’t even know they were there. I came out of the studio and there they were. Sitting in the room there, like, “Can we do anything?” It was fun. It was great.

Your album ‘Rant’ from over 20 years ago, set you off on another run of great albums. Was the song ‘Ripoff’ about your feelings of Britain at the time?

I guess so. It’s 20 odd years ago, so I can’t really remember where my head was at that time. But I would imagine so. It was one of them when I met Andy York. Mick had gone and I’d sort of stopped for five or six years and meeting Andy York, it was a big one. It was like meeting another Mick. So ‘Rant’ is good. One of the best to me.

What about ‘When The World Was Round?’ That’s got some great imagery in the lyrics. Do you recall writing that song?

I just remember ‘Too much information, not enough to go on.’ That’s all I remember. I liked that line. Sometimes you’re writing and you’re piddling around and a line will make all that difference. It’s between like that could be a song or no, this is a song. That’s all I remember about that particular track. It’s been a lot of stuff over the years, you know what I mean? My memory is not that great.

Yeah, there’s a lot of songs. That song in particular, there seems to be a thread with some of the themes on your new album in a way. Slight disillusionment with what’s going on, but in the end there is some hope. Yeah, I’ll just say it as it is.

‘Dandy’, I’ve read that it was about David Bowie, is that right?

Yeah, good song. I think it was called ‘Lady’ or something else. Then that happened to David and ‘Dandy’ just fit. I was already working on the song, and it had a different lyric. I just transferred it when I heard about Dave. Because we owed him. [laughs]

What are your plans? Do you think there will be a Defiance Part Three or are you working on a different project?

Oh, you never know. Yeah, I’m working and yes, I’ve got tracks. But not too many. I stopped for five, six years once. The minute I say I’m on a roll, I’m not. It’s something you don’t want to talk about.

Further information

The podcast version of this interview will be released in April.

Ian Hunter: ‘Definace Part 2: Fiction’ is released on Sun Records on Friday 19 April 2024. A limited edition 2LP vinyl edition featuring 3 bonus tracks will be available exclusively on Record Store Day, set for 20 April.