Gerry Beckley explains the inspiration behind his new self-titled album while recalling the origins of America. He reflects on the creative process behind ‘A Horse With No Name’, ‘Sister Golden Hair’, and ‘I Need You’, shedding light on their collaboration with George Martin and their meteoric rise in the early 1970s. Gerry also discusses the evolution of America, highlighting their resilience as a duo. Throughout his conversation with Jason Barnard, Gerry covers his influences and songwriting ethos, offering a glimpse into the everlasting nature of America’s music.

Your lead single, ‘Crazy’, has got a Beach Boys/wall of sound feel. Was that something that you wanted to emulate?

I’m a huge fan of that, of course, and I have quite a bit of history with it myself. But long before that, I loved all that stuff. Like all of us that dig deep into that, I know the building blocks that make that up, it’s one thing to have all those guys in the room playing.

I knew quite a few of them. But it’s not rocket science. It’s obviously not just to throw it all in the mix and out comes your wall of sound. You need your castanets, you need all of that stuff. But yeah, I love it. ‘Be my baby too’. Brian was always, as you know, a fanatic of that stuff. So I’m not alone.

This album is self-titled, so that’s a bit of a statement.

Yeah, not for not trying. There were a few titles that we kicked around. It wasn’t like, oh, this one is somewhat special for some reason. We haven’t had a self-titled one before. But there were a few titles that I liked and they were a little bit of an inside jokey kind of thing.

And much as, my friends and I would know what that’s about, or it’s an H title or whatever, like the America albums, I didn’t really want to have to be explaining it every time, you know? I thought, well, I’m going to be shooting myself in the foot. So let’s just go with the self-titled for this one.

Given it’s self-titled, how much of the album did you play yourself and how much did you get outside help?

I guess the answer is a lot in both. I play a lot of this stuff myself. We have a lovely home in Sydney and we have a home in Venice, California. I have studios in both places, but they are far more production rooms than what I used to have. I used to have a much bigger space with a grand piano and a full drum kit and everything. So I will farm out some of those things.

I’m not a great drummer, but I’m adequate on certain things. So I kind of miss having a kit just to mess around with, but I know so many lovely drummers and stuff. So it is an opportunity to bring other people into the fold.

Can you give us a bit of a flavour on what to expect for the rest of this album. Are there love songs, is there a shift in sound?

‘Crazy’ is one of the bigger productions. It has got a lot of what I call the kitchen sink. Everything’s in there and the horns. I really did spend quite a bit of time on that. I’ve got great horn sections, although not on that one in particular. I’ve got Doc from Tower of Power and Barry on one or two of the other ones. So I have the right guys to go to when I need it.

But there are a few tracks that boil it right back down to being very simple. I think that’s the challenge with an album. I’m old enough to come from those days of: you put on side one and then if you really love it, you flip it over onto side two.

The whole thing’s a 40 minute experience, which is really lovely. But you can’t just throw 10 or 12 songs in a row. I think that’s the trap everybody fell into with CDs where it turned into just one side. Then there was the dilemma of, oh, we’ve got some great stuff, but if we don’t front load the CD, people won’t get deep into the running order. So a lot of things were lost.

I always come from the challenge of making a real listening experience. I know what I’m up against because I have kids. I know that it’s hard for them to get through one song, let alone a side, but I can hope.

Your next single ‘Red and Blue’ is very soulful. Can you tell me about its message?

It’s something any of us who are politically aware can’t really avoid, to be honest. America were in red states as much as we were in blue states, and I like to think it’s an opportunity for everyone to come together and put everything else aside and let’s let the music be the message.

How does this album compare with your previous one, ‘Aurora’?

‘Aurora’ was done with similar studios and setups, but it involved quite a bit more lockdown. I hate to consider anything positive about the whole COVID experience because it was so tragic for all of us. But we were all forced to take a test that none of us asked for, which is, now what would you do if you can’t do what you do? In my case, all of my writing and recording had been done for decades, kind of in the gaps in between. You’re home on Tuesday, you’re leaving again on Thursday, quick!

You’ve been dying to get that bit down on a certain track. And COVID gave me the opportunity to do that. So ‘Aurora’ came out of that. It was the first time in years where I could actually spend a little time, but the whole thing still had that very strange overtone of being careful where you go and wear your masks and all of that stuff. This one, on the other hand, is really the freest I’ve felt in a long time because I really wasn’t under the gun.

I’m so fortunate to have a lovely boutique label with Blue Élan that liked what I do, because I understand how hard that is. So many of the singer-songwriter ilk, it’s really almost a non-existent thing now. So I appreciate how lucky I am. And Kirk, who’s been a dear friend, but also a fan for a long time, will come to me every year or so and say, “Have you got another one in you?” And I go, “Great, do another one.”

Blue Élan did a lovely collection of your solo work ‘Keeping The Light On’. That’s got ‘Watching The Time’. That song has got a connection with Carl Wilson, hasn’t it?

Yeah, ‘Watching The Time’ came from an album we did called ‘Like A Brother’. I was in a six year project with both Carl and Robert Lamm from the group Chicago. And it was best times and worst of times because we started with this, we did a session for Robert and we sang some backup and had such a great time.

We thought, oh, we should do an album. Not really thinking through that if you overlapped the Chicago touring schedule with the Beach Boy touring schedule. There’s very little daylight on the calendar. Then if you threw the America schedule on top of that, absolutely no time at all.

So it took six years to get what we did. And unfortunately, as is well known, in the last year Carl was diagnosed. So we put it on the shelf. Carl passed away within a year, which is beyond tragic. Then fortunately, Herbie Hancock had a small label and said, “I’d like to put it out anyway.” Everything about that I loved, except it’s beyond measure how tragic the ending was, but the experience of making the record and doing that song and the other 10 or 12 was really fantastic, lovely.

Going back to your ‘Aurora’ album, there’s a song on there, ‘Tickets to the Past’, that’s got an early America feel. It does seem quite nostalgic. Was that a song that you really wanted to dive into the early 70s?

Yeah, those are still my bones, that’s the kind of tools that I go to. I have all the gadgets and tricks and stuff, and I can just sequence up a lot of modern stuff, if I really wanted to. But to be honest, I don’t really go there too often.

I still love the magic of something coming out of your head and heart, through your hands, into an instrument, piano or lovely guitar. It doesn’t mean you can’t stretch it a little wider in the arrangement, but the basic bones I really like to keep. That’s kind of my area.

You also wanted to recall your early years with the lyrics.

That one in particular. Obviously, at my age, there’s a lot more looking back than there is looking forward. I remember decades ago, because I’ve been doing solo records for a while.

Clearly the challenge for guys like me who are still really into it is we’re not being forced to do this stuff. I use Brian’s line, ‘I’m bugged at my old man’, from The Beach Boys. That’s all great when you’re 18, maybe 25. But even by 30, it’s a little bit weird to start to have that be your themes. So the challenge is, as you add the decades, what can you really make that is pertinent, that doesn’t just sound like the Mr. Pipe and slippers talking all the time, saying listen to me now!

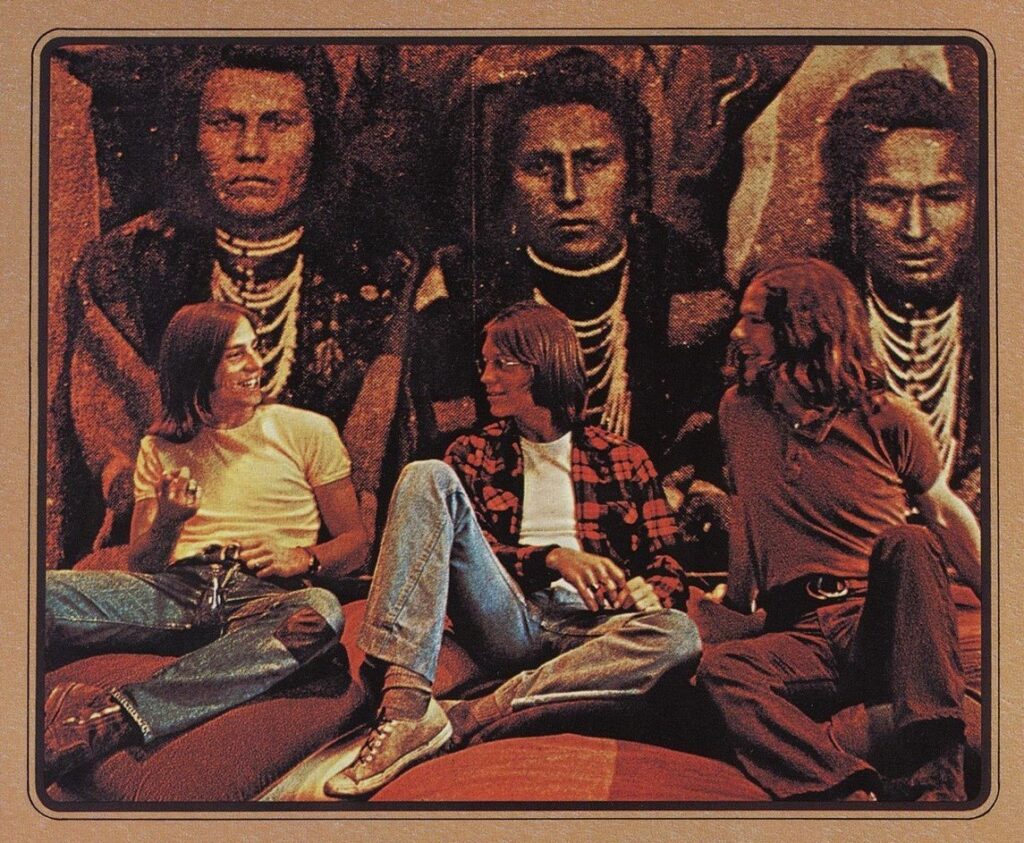

Take us back to the late 60s. You and Dewey were in London and your fathers were in the Air Force. Is that right?

True. Jason, we were stationed, and we went to a school called London Central. Which I say it was neither. It wasn’t in London. It wasn’t very central. It was up near Watford. My dad and Dew’s dad were at a base outside of London called Ruislip.

That’s how we met all of the kids, the dependents of the servicemen went to this school, London Central. And we met in 67, 68, our junior year of high school. Along with our third member, Dan, we played in high school bands. That was dance top 40 stuff that played at the base every weekend.

We graduated from high school in 69. By that time, I had started to do a few sessions in London. And I knew that I was going to stay there. Both Dewey and I had English mothers. I was going to at least hang out there with London, a fantastic city for music, as you well know. So I started to get to know a few people.

Dew said he had some original material, and I had started writing some stuff. Dan went away for about a half a semester of college, which didn’t go well. And he came back and he had been writing. So we started sitting around in each other’s houses. By that time, the guy with an acoustic was really blowing up, James Taylor, Crosby, Stills and Nash. So the three of us with our acoustics were singing harmony. We weren’t reinventing the wheel, but we were certainly there near the start of that. That led to the first album. Then the first album blew up. ‘Horse’ wasn’t really on the first album, it was added to it. Then it was kind of a 10 year rocket ship, we held on for all our might and survived.

You were recording at Morgan Studios out of hours because there’s some of that early material where you are singing like ‘Today’, for example. So you were honing your chops in the studio by songwriting which laid the ground for America.

Yeah. I don’t know how that stuff came out, but I know I did other sessions. But the majority of my stuff, I was doing at Morgan in Willesden. There was a guy named Chris Neil, and he was hired as an A&R guy or something, or he was going to write songs for their publishing.

So he started using me on his demos, and I would swap, I played bass on this, or keys, Wurlitzer or something. Then they’d give me some studio time. That was how I got started. Then I think what happened when Morgan finally sold, it went through quite a few different incarnations.

But I think somebody ended up with that archive of all those tapes, because when that stuff started showing up, I think the album that came out said something like Discover America or Discovering America. In the credits, it says, truly, this isn’t really America, but it’s Gerry’s earliest stuff. You’ve got to be careful when the early stuff comes out, because it’s usually a little bit cringe worthy.

There’s a lovely story because I was playing with these other guys doing sessions for singer-songwriter Phil Reed, and he was cutting stuff. When his stuff was being shopped around, the story goes that the A&R guys at Warner said, “I don’t really hear it.” Then a guitar solo that I played came on and they said, “Well, who’s that?” The guy who was shopping us said, “Actually, that’s an American kid who was on the session.” They said, “He’s got a band.” And they said, “Well, bring me his band.” So that’s how we got into Warner’s late 70, early 71.

I’ve read in Jude Warne‘s biography of America, that ‘I Need You’ is influenced by The Bee Gees’ ‘First of May’, is that right?

Of course, one of many songs. I loved the Gibb brothers from the very earliest days. In fact, personal favourites are all of that early stuff, ‘Holiday’ and ‘Mining Disaster.’ ‘First Of May’ has the line, ‘When I was small and Christmas trees were tall, we used to laugh while others play. So I just grabbed, ‘We used to laugh’. I loved the phrasing of it and put it at the start of a tune and I was off and running.

What were Dewey’s influences for writing ‘A Horse With No Name’?

There are quite some pretty serious influences on that, including Neil Young at the top of the list. There’s a lovely quote in Neil’s book which we knew anyway, where his dad called him and said, “I love your new song about the horse. This is great.”

We came up right in that era. Thank God for John Peel. He was such a great source at that time. We were playing the Roundhouse. Jeff Dexter was booking us. We were on unbelievable bills. We played the Oval with The Faces and The Who, and I think Vince Crane and Atomic Rooster. I have great memories of that time.

I’ve read that ‘Horse’ was demoed at Arthur Brown‘s house.

The guys who were in the Crazy World, they had some kind of farm and they used it as a demo facility. I think you could hire it out and Warners knew about it. So we went down there. What happened was we’d done the album. Everybody loved the album but they weren’t really convinced. It’s the classic we don’t know if we hear a single.

So they did an amazing thing and said, “Do you have anything else?” Well, nowadays that really wouldn’t happen. They wouldn’t say, right, the album’s done. Now let’s put you back in. They’d wait two or three years and see if their investment was paying off. But in this case, thank God, they said, “Have you got anything else?” And we went in and we went to that place and we had three or four songs, which we rehearsed. We kind of liked them all, “Here’s the new batch.”

We weren’t really sure what they were going to say. It was a lesson that we learned very early on, believe it or not, sometimes it’s a good idea to listen to the label. Everybody always figures that you’re pitting yourself against the suits that don’t know anything. But in this case, they said, “Oh, it’s got to be Horse, the desert song.” So we went in but we couldn’t get into Trident where we’d done the album. So we went to Morgan. So I was back at Morgan, which is where we cut ‘Horse’.

It was a huge success, a number one single. That must have been mind blowing.

It was mind blowing. In particular, it was mind blowing for everybody around us. Not only was ‘Horse’ number one, but the album went to number one in the States. So we had the simultaneous number one album and single, not even The Beatles had done that.

I’ll tell you how rare that is. That didn’t happen again until The Knack with ‘My Sharona.’ So the honest story is that the three of us were thinking that you put out a record, you really love it, it’s going up the charts and yeah, great. But the people around us, the label, couldn’t believe it. Warners, as much as they were a representative of the mega American motherload, by no means did everything that they signed get even released in the States, let alone show up in the charts.

So for Warners UK, Ian Ralfini and Martin Wyatt and all these guys, all of a sudden have a number one record in the States. It was really something. That starts that whole thing, it’s very hard to follow that, that’s what we call the sophomore jinx in the States, your second one. We cleared all those hurdles. We did very well. The second album actually sold more than the first. And so it was a pretty amazing time.

The pull of going to the USA must have been strong. You did go and base yourself back over in the States.

We went over to do a tour in order to get that album and single released. Because as I was saying, not everything that Warners signs in the UK gets even put out. And because it was a big hit in England, Mo Ostin and Joe Smith said, “Sure, we’ll put it out. If they’ll come over and do a club tour.”

We said “Of course we’ll come over. We’re just playing every pub in England anyway.” So we were flown over and we were booked to open for the Everlys for the first few weeks. The first shows in the States were in DC at a famous little club called the Cellar Door. There was a line around the block to see us, which was lovely, but we were only booked for like 20 or 30 minutes.

The Everlys were fantastic. They were touring with Pop Everly, their dad. The band, I’ll never forget, had Warren Zevon on keyboards and Waddy Wachtel was on guitar. It was 1972. So it was fantastic, but everybody there had no interest in seeing the Everlys.

So they’d listen to a couple of tunes and leave because they’d come to see us see these kids from England. So the next week we were supposed to do the same thing in a little club outside of Boston and the Everlys got sick, supposedly, basically cancelled. The guy said, “It’s okay, man, the phone’s ringing off the hook.” We only had like 30, 40 minutes, we’d only been opening for everybody. He said,”It’s okay, I’ve hired a comic, this kid named Jay Leno is going to do like three weeks.”

So we had Jay Leno opening for us. Then it just blew up. By the time we hit the Whiskey, which was the last week in the middle of March, it wasn’t quite number one, but it was clear it was going to be. We were booked for a week, sold out, lines around the block. It was really lovely. It was just hyper speed. Brian Wilson was coming on multiple nights and it was pretty amazing.

The songs in that period are timeless. ‘Ventura Highway’ being an example. Was that about travelling in the States?

Yeah, Dewey wrote Ventura and had lived in California. I had never even been to California until we played the Whiskey. But I know the imagery. In fact, Dewey was in his mind just trying to dredge it all up. They lived at Vandenberg Air Force Base, which is on the California coast. So there really isn’t a Ventura Highway. There’s the Ventura Freeway, there’s Ventura Boulevard, there’s a town of Ventura.

But he was just bringing back all these memories. But he’s writing the song in our little rain-soaked cottage up in Chipperfield in Hertfordshire. So that and Horse were coming out of Dewey’s head. But boy, did it fit the moment, because it’s kind of top-down music, and it’s classic to this day.

How did the songwriting work? Did you write your songs individually? Or was it a bit like Lennon-McCartney who would bounce the odd idea against each other?

There was a bit of that. We didn’t ever, at the time, co -credit. And I would certainly don’t want to take any credit on Dewey’s tracks. But we did help each other out a little bit. Like, I was pretty good if a song needed a bridge, I could come up with a few chords, just a left turn if the thing needed a little bit of air. And likewise for Dewey, if he heard a little counter melody line, he would say, “What about this line?” So we did.

But they were usually just credited to whoever sang it. Like, “I Need You”, I sang. That was mine. ‘Horse’ and ‘Ventura’ were Dewey’s. Dan had a big hit with ‘Lonely People’. That’s him singing that. Years later, that’s blown up. If you look at the hits today, they’ll be 10 or 15 writers. I prefer the old style myself.

Obviously, George Martin’s work with The Beatles, is some of the best production ever. But to get him involved in your material, how did that happen and what was working with George like?

First of all, we did the first album in London. We then came over and did album two and three in LA and San Francisco at the Record Plant. The second album was a huge hit, Double Platinum, but the third one was really struggling. We then decided before we started on the fourth album that maybe it was time to turn this over to a producer. By now, the live show was building up. Our years were just getting soaked and recording the third album had taken us quite a lot of time and you’re up all night.

So we thought, who can we get? We made a very short list. To be honest, I can’t remember who else was on it but top of the list was George. We just thought, “well, you can ask. I mean, all you’re gonna hear is no thanks. There’s nothing wrong with asking.” So our management set up a meeting and he happened to be coming to LA anyway. So the timing was really good because he was nominated for ‘Live and Let Die’. He had worked with Paul on the James Bond score.

So he was there anyway. We were not an unheard of thing. We’d had a number one and numerous hits around the world, two multi-platinum albums. So it wasn’t like we were asking him to take on this unheard of. George was certainly looking for other things. He had built a beautiful facility, Air Studios in London. He had finished his deal with EMI and was working on some lovely things. But I think we fit the mould. All of a sudden, here’s another batch of boys, young guys who sing their own songs and sing harmonies. You can see how it fits. He said, “The only thing I ask is that you can come to London, I have a lovely new studio. I can’t be gone too long. I can’t be gone for months.”

Dewey and I and Dan, we’d all lived in England. There was absolutely no problem with that, “We’d love to come”. When we came to Air, he told us that he had held two months. He said, “I’m not saying we’ll be done in two months, but I’ve held two and we’ll see how we go”.

We did that album in 14 days, the whole thing mixed and everything overdubbed and which just shows you. There’s a great quote in Jude’s book where he says, “Lads, this has been so fantastic. It can’t possibly be a success. Nothing that easy can be a success.” Fortunately for him and for all of us, it was, and it went on to be a multi-platinum album and ‘Tin Man’ and ‘Lonely People’, huge hits from that record.

What about ‘Sister Golden Hair’? Because that is one of your songs and that’s got an influence from Jackson Browne.

Yes, well, there’s quite a few influences, again, on that one. I actually had ‘Sister’ for the previous album, for that first George Martin album. But I liked the songs that I had brought to the table. I always knew there’s going to be another project. They don’t all have to fit on. When there’s three writers, there’s only three or four, basically each. So anyway, it was put on hold until the next album, but it was like front and centre for the next album.

We had toured with Jackson. The reason that I make that mention is that, first of all, he’s one of our greatest living songwriters. But the thing that I in particular loved about Jackson was his ability to make things conversational. That when you listen to a Jackson Browne song, it’s like a conversation. It isn’t just, onomatopoeia rhyming lines two and four and one and three. It’s like somebody talking. I thought, it’s really great. I was trying to do that. Trying to just make sentences that ran together and were more than just lines of a poem. The other thing is, of course, sonically, with a 12-string acoustic and a slide guitar is very much kind of a ‘My Sweet Lord’ homage there.

You must have been in such a writing groove around that time because there’s ‘Daisy Jane’ as well. This is just timeless material.

Thank you.

Was it clear to you that you were in a really good moment?

I was looking at the long list of people you’ve spoken to, including some of my true heroes like Graham Gouldman. I do know Graham, but I guarantee, when you ask any successful writer, they’ll tell you that you can feel it when it’s going well.

‘Daisy Jane’ was one of those. I had a lovely cottage in Sussex in the South Downs, it had a little upright piano. It’s where I would go if we had any time off. I just started banging that out. It took about the time it took to play it. I just thought, “Oh boy, it doesn’t need much more than this.”

I remember playing it for Eric Carmen, who was a friend of ours who just passed away. I had eight bars of just basically the intro again. It was like the song, it just happens twice. He says, “Well, what’s gonna go on there?” I said to him, “I don’t know, George will come up with something.” That shows you by our fifth album, the second one with George, he had become a part of the band – “George will score a lovely little something to go in that gap”, which he did.

By 1976 you had the greatest hits album, there was the Bicentennial Weekend with The Beach Boys and Santana. Did it feel that you couldn’t really get any bigger? It must have felt that you were, again, in a high spot.

That’s very true. There have been occasions where people on that rocket, for some reason, expect the rocket to just keep going in that direction. It’s like, haven’t you ever seen them? Rockets eventually arc at least, if not, start heading severely in the opposite direction. But in our case, I can honestly say, I really do remember and recognise that moment.

I do have a particular time. We had done hundreds of shows with The Beach Boys and we always used to mooch a ride on their private plane. It was the only way you could do the fixed schedule that they had. So we were coming back to LA. We had done a whole summer together and we’re landing very late at LAX. Audrey, the mother of the Wilsons, was still with us. She was travelling a lot with Carl. Dennis was still alive at the time and we landed in LA and all the big cars, the SUVs or the limos were pulling up. I remember thinking to myself, I just don’t think it could ever be any better than that.

I remember freezing that moment in time because you don’t want to let three years go by and think I wish somebody had told me back then. I remember thinking, okay, there’s nothing wrong with that. I think that the mistake is when people don’t recognize it or get upset that it doesn’t last forever. It doesn’t matter who, who it is. It’s not going to last forever. So you’ve got to try and wrap your head around that.

Then Dan left, did you guys adjust to that okay?

It was a challenge. It wasn’t something insurmountable. The truth was we were not able to work. Dan was really not in great shape. We couldn’t book anything. If they did book something, he wasn’t physically ready to go out and do it.

It was clear that he was wrestling with a lot of things other than just the band. He went through a religious rebirth. He had been raised a Baptist in a pretty devoted family So, as I’m sure you know, it’s very easy for the wheels to come off when the car’s cruising at that speed for any length of time. So, it was really a positive thing, a win-win, and it doesn’t sound like it. But it allowed Dan to sort that stuff out in his life, which he did.

He then went on to do some contemporary Christian albums. He was nominated for a Grammy for one of those. He did very well. He passed away way too early, but he couldn’t have carried on in the band. By him leaving, it gave Dew and I the freedom to carry on. We said, okay, it’s two of us now. It took a little while to figure out what shape that was. But within a few years, we were back in the charts with ‘You Can Do Magic’, and we changed labels. So, there was life after Dan, which I had never really questioned. We just weren’t sure what shape it would take.

Before ‘You Can Do Magic’ is ‘All My Life’. Again, that is in the top tranche of America songs. Was that a song that you kind of plucked out of the air or was that related to anything personal?

I love a ballad. I’m kind of the ballad writer in the band. So there’s usually one or two in each album. And ‘All My Life’ really clicked for me. I thought, this is great. We had changed labels. Capitol Records was kind of at a loss. Didn’t really know what to do with us. And it came and went. We were always travelling internationally.

We learned a long time ago that you should do a little research because not every song is the same. The hits aren’t the same hits in different countries. And we were down in the Philippines and they said, “You gotta play ‘All My Life’.” We said, “We don’t really do it. It’s not in the show.” They said, “Oh, it’d be a great mistake if you don’t do it.” So we had a little pow wow. It’s the kind of thing that I could do solo on the piano or the guitar.

So we decided to put it in the middle of the show. It’s three minutes. I’ll sit at the piano.You guys go get a drink. If it works, we’re good. If it doesn’t work, we’ve got the whole rest of the show and we’ll just carry it. It won’t be too big of a hiccup. So for the first time ever I’d done this, I’m sitting in a huge folk art centre, very large venue in Manila. There’s no intro to give it away. I just go ‘All My Life’. And the place just went apeshit. It started screaming. And this is good, it’s better than the opposite. But I started to shake. It took me by surprise. Anyway, I grabbed a hold of it, finished the tune and everything.

Dew came out with this big smirk on his face. Like, “That went well.” So we, of course, moved it to the end of the show. It became the encore. So we learned a lesson there. Always do some research and figure out. But not all these songs, not every song is a hit everywhere. I always felt that it was a very strong ballad. In the States it didn’t get the attention it maybe should have.

You mentioned ‘You Can Do Magic’, another huge hit for America. But this time you were working with Russ Ballard. How was it having an outside producer and writer? It’s not always an easy dynamic.

I was doing a lot of vocal sessions in LA. So I had a little more experience with different producers and how to get along and how to keep the ball rolling. In Russ’s case, we were doing the album ourselves. It was on the ‘View From The Ground’ album, but Russ had submitted this song. He’d actually written it for us or supposedly, but part of his deal was that he would produce it.

He had had a hit with Santana with ‘I’m Winning’, I think by this point. And I said, “Sure, I’d love to.” Ironically, we ended up at Abbey Road. So for all of the times with George Martin, we never got to Abbey Road. Now the minute we’re not with George, we’re in Abbey Road, it’s a little inside out.

But the other thing about Russ is he plays every instrument. So for Dewey and I, there was a little bit of, okay, interesting experiment. But it was a huge hit. You can’t argue with the hit and it’s a big part of the show for decades after that. But as a result of that being a hit, the next album, they said, well, Russ has got to produce the album. So we ended up in a situation where Dew and I were sitting on the couch a lot, while Russ cut all the tracks. A little weird. I prefer to play if I can.

A few years ago, you featured on a new version of ‘This Is Not America’. Robert Lamm and Bobby Woods were on that. But I wanted to mention that as you’ve got a few ties, it seems, with David Bowie. You guys played on the same bill as David in the early 70s. You also worked with him in the early 90s.

There’s a YouTube clip where we are having a chat and we’re in the studio. I did know David, not very well. I don’t think we did any shows later on. I got to know David because I was basically rooming with Ronnie Wood. This is a whole other tangent, but I would stay at Ronnie’s house when I was in London and he and his first wife would stay at my place.

So to have Ronnie as your house guest was a 25 hour a day party usually and all kinds of fascinating people. This is right from The Faces into getting the gig with The Stones. But Bobby Womack would be up there and Dr. John. He brought Bowie up a few times. So that’s how I kind of got to know him and somehow survived all of that, as did Woody and we’re still here to tell the tale.

Just over a decade ago, America did an album of cover versions. You did ‘America’, the Simon and Garfunkel track. Earlier in our conversation you mentioned the flow of lyrics and that’s a great example of where the lyrics don’t necessarily rhyme, they flow in a natural way.

It’s maybe the best example of that. I don’t know if you saw it, but a couple of weeks ago here in Sydney, we had a lovely week. I don’t go to a lot of shows, but in one week we saw Graham Nash, and two days later we saw Wilco.

So we were hanging with Wilco going to see Graham, and two days later, we were hanging with Graham going to see Wilco. So it was a lovely week, but the reason I mention it is, Graham got back to the States and sent me this clip that was me talking about the genius of Paul Simon in that song. I don’t know if you’ve seen that article, but, and I didn’t know about it.

So I’m glad that Graham sent it to me, but I used to lecture at Loyola and I would talk about rules, no rules. The point of the talk to musicians studying music was that there are these fundamental rules in popular music that are like three minutes a song and verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, all of these building blocks. I would then show shining examples of great work that breaks the rules.

So I’m trying to establish this one tool: it’s good to know the rules, but also please understand that you can break these rules a million ways and do it with wonderful results. The song ‘America’ by Simon and Garfunkel I would use this as an example. I would play that and these other songs in the class and ask all of these very bright kids, who have listened to music their whole lives, “What’s unique about it?” People would say, “It’s in six-eight” all true stuff, but nobody got that there’s not a rhyme in the whole song.

The entire song is prose. I can tell you some of the best songwriters are totally hooked on their rhyming dictionaries. They’ve got all their favourite words, high lit and stuff, because it is fundamental, one of the big building blocks of writing popular music. But that song is an example where you’re so involved in the lyric that you don’t even think, wait a minute, that didn’t rhyme with the last line. It’s all prose. Not only is it prose, it’s like the most beautiful little three or four minute indie film, frankly, you can visualise, counting the cars on the New Jersey Turnpike. I love it. And I have to say, I’m not a big fan of three, four, waltz and six-eighths and things. They aren’t my go-to time signatures. Then I’m reminded that, well, how do you explain that then? It’s one of my favourite songs of all time.

Maybe that’s one of the themes of our discussion today, the magical nature of songwriting. You can’t pin it down, but when you hear great music, you know it. That’s certainly the case with your songs, Gerry, as well as Dewey and Dan’s in America. All the best with the new album. I’ve loved what I’ve heard so far, and I look forward to hearing more.

Well, let’s talk again after you’ve heard the album and good luck with the rest. You’ve got an amazing list of people you’ve already spoke to and I’m not sure who you’ve got coming up, but I’m honoured to be a part of it. Thank you, Jason.

Further information

Gerry Beckley’s single ‘Crazy’ is out now. It is from his forthcoming self-titled album.