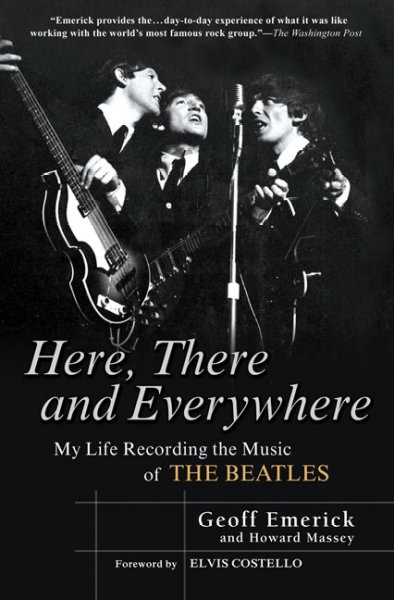

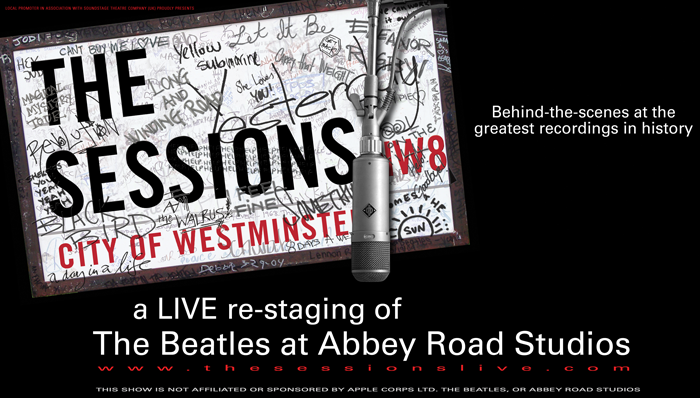

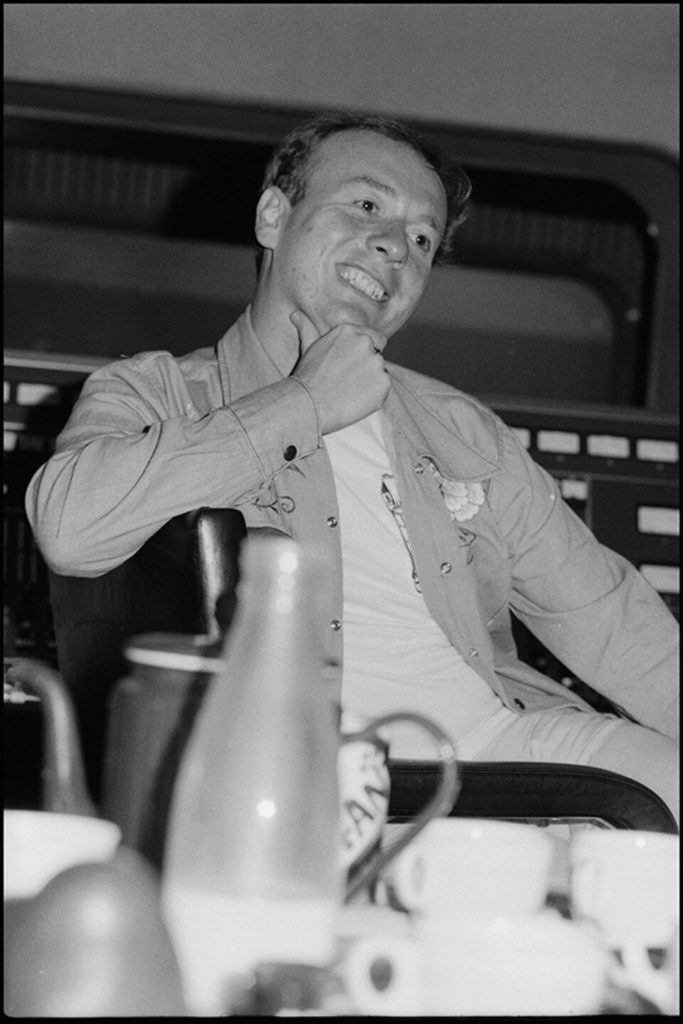

With the Soundstage Theatre Company, formed by Jef Hanlon in the Spring of 2015 to present THE SESSIONS – The Beatles At Abbey Road to the world, finally being dissolved on August 31 2022 following it being placed into voluntary liquidation on July 4 2016, it seems appropriate to present a transcript Jason Barnard of The Strange Brew Podcast’s interview with Geoff Emerick whose book Here, There and Everywhere inspired the show. The interview was conducted on April 6 2016. Unbeknown to Geoff, this was also to be the date of the fifth and final outing for THE SESSIONS as, within a week, the tour had crumbled. We also embellish the interview with a postscript that puts the fate of the show into perspective.

This discussion captures more optimistic times. He was completely unaware of what was lurking around the corner.

So Geoff, THE SESSIONS show is in the middle of a European tour and so far, from what I can see, it’s been fantastically received.

Yeah.

From what I’ve heard, it really does show how the songs evolved in the studios when you were working with The Beatles.

Yeah, basically, we’re presenting the songs as they ended up on the records, as best we can. And, to me, they sound like the finished record. So what we’ve done – first of all the stage set is number two studio Abbey Road. There’s a George Martin narrator that tells the story from the beginning to the end, going through the albums. The mikes on stage are near to the microphones we used to use for vocals so, when Paul and John were singing around one mike, we’re doing that as well. It’s extremely complicated to do it and, when we’ve done double-track vocals, there’s two Pauls and two Johns and two Georges. Nothing’s pre-recorded per se. All the vocals are completely live and the Ringo drummer is on stage but the actual Beatle band is behind the stage set, but the Beatle guys themselves, they can all play guitars. So we’re just presenting the 60 songs, not all in their entirety, but they sound just like they did on the record and it’s really amazing. The lighting’s fantastic and there’s the sort of see-through walls that surround the stage to begin with, with great graphics on, and it’s just the most amazing thing. Stig Edgren, who’s the producer of this, when we first talked about it some six years ago – because he read my book, which was recalling the music of The Beatles – he said, ‘Do you think it would make a musical?’ So it’s been, like, six years in making this really.

Yeah and I’ve been to many a Beatles-related show and this one uniquely seems to show how the songs evolved in the studio. I’ve got a little fact for you actually. It is 50 years today since the recording of ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’. I don’t know if you knew that?

Oh really? I didn’t know that. Thanks for telling me.

Obviously it’s an absolutely pivotal track in the history of music, as such, but it’s a pivotal track in terms of your role with the Beatles as well?

Yeah absolutely. We actually do that in the show and it’s a really good representation of it with the backwards guitar and everything. But, yes, that was when I was dropped in the deep end when Norman Smith left – the original recording engineer – and that was the first track they recorded for the Revolver album. It started by John wanting this magical voice – the Dalai Lama singing on a mountain top 20 miles away from the studio. There was no software in those days and no plug-ins so my saving grace there was the revolving speaker from the Hammond organ, which was called the Leslie speaker, and we put John’s voice through that and that won John over in fact in a big way because he just loved the sound of that. And then Ringo wanted a different drum sound, and we got that, and Paul wanted a much stronger bass sound, and we got that, so that was like the beginning really.

And it’s interesting that I understand THE SESSIONS takes you through the Beatles journey chronologically from when they were first at Abbey Road and you understand you were a witness at the first ever EMI session for them?

That’s right, because it wasn’t their artist test, but I’ve started whatever date it was – the sixth of June [1962], maybe? I can’t quite remember. So, anyway, I started at EMI studios and two days later they came in to do their first recording which was ‘How Do You Do It’ but as they didn’t want to do that they did ‘Love Me Do’. I was learning the ropes to see the job that I was about to do so I asked if I could sit in on the session, which I did.

And the other thing as well that’s interesting is how the songs changed and how the equipment was used differently and how things progressed. ‘She Loves You’ seems to be one of those tracks where you’re working with Norman Smith?

That’s right, yes. And then the girls break into the studio, which is sort of recreated a little bit on our presentation, and then they go into ‘She Loves You’ but because that happened there’s so much energy in that track.

And similarly there is ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand’ and I understand that was the first using four track recording and that was pivotal as well?

It was. Correct. Because four track was just coming into being and it was saved for the top artists at that time like Cliff Richard, The Beatles weren’t actually put into that top artist slot at that time, I don’t think. Believe it or not!

And I’ve read your book Here, There and Everywhere. It provides a window into recording with The Beatles and you tell us some really good stories. I assume that this is represented in THE SESSIONS as well? For example, ‘I Feel Fine’ with the feedback?

Yes. That’s featured in THE SESSIONS.

And there’s a line in Here, There and Everywhere which seems to indicate to you that The Beatles were looking to stretch the boundaries [in ‘I Feel Fine’]?

Oh yes. In the show there’s the actual part where he [John] leans the guitar up to the amp for the first time and then he says ‘Oh. Can we use that on the track?’ up to George [Martin] in the control room, so then we do the track.

I was wondering if ‘Yellow Submarine’ was in the show actually?

Yes [he chuckles]. That’s great. Everything’s great to me. But, yes, ‘Yellow Submarine’ is there.

I assume that’s a great opportunity to show the visuals on display in THE SESSIONS?

Yeah. It’s just great. Everyone’s gone overboard, from the lighting to the graphics to the musicians and stuff.

I’ve heard that you’ve assembled a world-class team for THE SESSIONS actually as well.

Oh, it’s unbelievable. I mean, everyone – and there’s great camaraderie. On the graphics at the beginning of the show it says ‘It takes 45 people to recreate the music and the genius of four people’ and that’s why there’s 45 people because there’s a 22-piece orchestra as well.

And speaking of orchestra, as well, it’s interesting – the studio seems to be like a real instrument at Abbey Road and a big song for that seems to be ‘Eleanor Rigby’ and you had a role in close miking the string quartet.

Yes, because we were always after new sounds all the time and, when George Martin suggested we use strings on ‘Eleanor Rigby’ and Paul said, ‘Oh well. I don’t want Mantovani strings, so let’s try a new sort of string sound.’ We ended up moving the microphones about four inches from where the bow hits the strings. It was a double quartet and the second desk, of course, kept sliding back on their chairs because they weren’t quite as good as the first desk and they were trying to get away from the microphones but they couldn’t hide themselves. And that was based on Psycho, on the shower scene, that strident arrangement that was done. So we decided to put the mikes really close to the instruments and because they said, ‘Oh. You can’t do that.’ Well, we did do that.

And then a similar way experimenting in the studio and especially on your part as well seemed to play a role in the single ‘Paperback Writer’?

Oh yeah. We’re talking about the bass on that?

Yeah.

We’re always striving for different sounds and new sounds and both Paul and I were very familiar with American records that always tended to have a lot more bass on them. So, being sort of naive as I was at that time, I guess because again I was so young, my theory was that if a bass speaker can push it out then the speaker can take it back in so I decided to use a speaker as a microphone. It was quite tricky to do but that’s what I did on ‘Paperback Writer’ and ‘Rain’ and now I believe, if you walk into many recording studios, you’ll find they’re using a loudspeaker for the bass drum and the bass.

Wow. Yeah the drum sound on ‘Rain’ actually is amazing as well.

Yeah. That’s Ringo’s favourite drum track, I believe. Because, on ‘Rain’, the drums are slowed down, which meant that, when we recorded the drums, we used a speed which was 15 inches per second. It’s hard to relate tape now to people. So we put that machine on varispeed, so it recorded a little faster, so we didn’t always have to put it on varispeed to play it. So, when we played it at 15 inches per second, it was a slower speed and that was the drum sound on ‘Rain’ which, as I said, Ringo loves that drum track.

Absolutely and, again, I assume this is featured heavily in THE SESSIONS and that’s ‘Strawberry Fields’ and again you had a major role in how that track took shape in the studio?

Yes. We do ‘Strawberry Fields’ and I’ll try and condense the story. John recorded ‘Strawberry Fields’ and was quite happy with it and two weeks later he came back and said, ‘I want to re-record it. I think we can do a better job on it and I want to be more strident and aggressive at the end using orchestral instruments.’ So it was recorded for a second time and then John came back and said, ’Well. I really like the first half of the first version that we did two weeks ago and the second half of the new version that we’ve just done.’ But the problem was there were different tempos and different keys. So, what we had to do was to copy our mixes that we’d done with the tape machines being on varispeed and then record it on a third machine. I might get this the wrong way around… We sent the first half – I had to speed it up. I’ll slow it down slightly to marry with the tempo and then the key of the second tape, or the second version, which was on varispeed and I think I slowed that down to begin with and then gradually sped it up as it reached the end. And then the actual edit is on the word ‘down’ which is about a minute into the song but I had to do a funny sort of scissory edit, because we didn’t have razor blades to do edits. EMI didn’t have razor blades. We used brass scissors. So I made a little cardboard template up with a couple of marks on so it wasn’t like a 45 degree angle. It was more like a crossfade. It was quite a long cut which was about an inch long, I guess – maybe longer. And it was like a crossfade rather than just a butted up edit. But it actually works.

My favourite song by The Beatles is ‘A Day In The Life’.

Well, yeah, of course.

That must be a fantastic song to hear live as well on the show.

Yeah, it’s actually unbelievable. I can’t believe that Howie [Lindeman], who’s the front of house sound man, and obviously the musicians in the orchestra part, have done such a fantastic job. It really, really is very close to the record and because, when we made that record, you had to be there the night that we actually put the orchestra on. Richard [Lush] who was my assistant, and myself, we did the rough monitor mix so everyone could hear it back, which was a little tricky at that time. But, anyway, we did it and a few of the Rolling Stones were there and a few other invited guests and they were standing in the control room and so was Ron Richards, who was The Hollies’ producer, who was sitting on the floor. So, eventually, we get it together and we play back our monitor mix, which is just a sort of a mock-up mix, not the final mix, and it was just unbelievable. Everyone was sort of open mouthed at the end of it and Ron Richards, who was sitting on the floor, he had his head in his hands. He said, ‘I’m just going to give the business up because I know I can’t get anywhere near that.’ I mean you really had to experience that night, what happened, because it was like going from a square, black and white picture into, like, cinemascope technicolor. It was just unbelievable.

Yeah. Sgt Pepper is an album that speaks for itself and ‘Being For The Benefit Of Mr Kite’ – you had a major role in terms of the sound effects on that one as well?

Well it was just a question, because EMI had a quite a large sound effects library, and we sort of chopped up various sound effects of calliope organs and steam organs and John’s directive, again, was ‘I want to smell the sawdust.’ And also we recorded some instruments at double speed or half speed to play them at twice the speed like little xylophones and little glockenspiels to give the little sort of circular roundabout sounds and the huffing and the puffing. There’s a harmonium in there and it was just a montage of just ‘stuff’ and I’m not even sure whether that exists on the 4-track because we had to send a lot of those sound effects from separate tape machines as we were doing the mix, so I’m not quite sure what is actually now on the four track on that – but it’s quite complex. But although it was complex, it was fun at the time doing it.

And from reading Here, There and Everywhere, a track that you’re particularly fond of is ‘Within You, Without You’ which noted George Harrison’s growth as an artist.

Yeah. That was quite amazing, actually, because during the book, as far I’m concerned, there’s an underlying story of George’s progression from early on through to the very end when he became a really prolific songwriter and just a fantastic guitarist. But, at the beginning, it sort of reads as though he’s got a little struggle and then he finds his niche in Eastern music and stuff and it gradually progresses from there so, to me, there was an underlying story of George.

And you started off work on what is now known as The White Album, which I think is commonly referred as the ‘tension album’, but I think you had a role with ‘Blackbird’ and that’s a song that stands out.

Yeah. Absolutely, because what happened on The White Album, I’d recorded about 10 tracks and because it wasn’t, as far as I was concerned, a very nice atmosphere in the studio, let’s just say that, I decided to leave. What happened that I was working with Paul in number two studio and John might be in number three studio working with someone else and then George might be in another studio working with someone else. So they were gradually splitting up.

And you left EMI to become Apple Studio Manager. I guess there were tensions there?

No. Well. I tried to shut that out because I went to Apple to rebuild Magic Alex’s studio which was really not functioning. So we gutted all that out and it took two years to build a new studio. In the meantime, although we were also recording the Abbey Road album, because Paul asked me to go to Apple and that involved recording the Abbey Road album. So it took two years to build that studio. In another two years it worked as a commercial studio, because they built their own little studios in their homes.

And go back to the Abbey Road album, I assume there will be plenty of tracks played live at THE SESSIONS. Such a great song is ‘Something’ and I understand that a lot of time went into that as one of George’s tracks?

Yeah. There was a lot of thought went into that. Yes we do ‘Something’ obviously. What happened there – George had done a guitar solo and he wanted to redo it. So, what happened, we only had one track to put the orchestra on. There was no more left because it was on four track and there was no other track. So there’s one vacant track and as George wanted to redo the guitar solo he had to do the guitar solo with the orchestra which was done in number one studio and we tied it up with the mixing console in number two studio. So, yeah, there was a lot of thought on it and he wanted the bass simplified a little bit from what Paul had worked out.

And you noted in Here, There and Everywhere Paul’s perfectionism and ‘Oh Darling’ seemed to be one of those songs when he kept re-recording his vocals.

Yes. That’s right. I think it was because he wanted to prove to John that he could sing it. Because, when you think about it, John could have sung it but Paul came in for quite a few days to try it and it sounds great. If you don’t know what goes on behind the scenes, it’s just brilliant.

‘The End’ off Abbey Road seems to be a landmark song with all the solos and the edits.

Yes, it all works out well. We end in ‘The End’ and everything and it’s just unbelievable. It really is. It’s just like listening to the records. It’s fantastic.

I asked people on social media what to ask you about and actually they asked me about loads of non-Beatles related stuff but I know you’re here to cover THE SESSIONS. One thing I wanted to mention was that I was speaking to Rod Argent and he said that he was particularly touched by your reference to your time working on the Odessey and Oracle album.

Oh sure, yeah. ‘Time Of The Season’ is just a classic. I remember vividly doing it. It’s just great. When did he read that I’d touched on that then or don’t you know?

He read Here, There and Everywhere.

Oh I see.

He saw what you said about working with them in those pages actually.

Oh I see. That’s nice.

You had a number one with Manfred Mann – ‘Pretty Flamingo’?

Yeah. That’s right. Yes. Because, when Norman Smith left, I was promoted to recording engineer and I took over a lot of Norman’s artists and it was like five months after that I was asked if I wanted to do The Beatles.

And another artist I spoke to recently was Mark Wirtz. You worked with him on ‘Teenage Opera’?

Yeah. That was, what, ’67? Yes I did. So you spoke to Mark recently did you?

Yeah. He’s in Atlanta. He’s in Georgia.

Yeah. That’s right. When I last saw him, which was many years ago, he was in Georgia and then I lost contact with him.

He’s still alive and kicking.

Oh great. You know what he’s doing, do you?

I think he’s just retired. He’s still trying to finish off the… He’s got a new album out, well he’s trying to get an album out, but he’s got loads of legal issues at the minute, unfortunately.

Well sure, sure.

He’s sort of bogged down in that. Self Licking Ice Cream it’s called.

(Geoff chuckles)

He’s as mad as ever.

Yeah. Oh is he?

And one album that people wanted to mention was Elvis Costello and Imperial Bedroom?

Oh yeah, sure, yeah.

I assume you used a lot of the techniques that you learned with The Beatles on that.

Yeah. I went overboard a bit. From a technical point of view I decided to record it, because at that time I think people started to record at 30 ips, you know 30 inches a second, and I decided to record it at 15 inches a second and I mixed it at 15 inches a second really to get that sort of that little bit of bottom end in it and also I didn’t want it to sound hi-fi because that didn’t really suit Elvis’s music. It was more, sort of, harder than, sort of, you know, sparkly. Also, in approaching that album, I pulled his voice way out up front because I used to like his lyrics but I had trouble sort of listening for the lyrics. That sort of threw him a little bit, for the first couple of weeks, because he’d never know… When we were doing monitor mixes, I had the voice quite loud and it took him a while to accept that but, eventually, he did.

Yeah. His voice is really sort of pulled out on songs like ‘Almost Blue’.

Yeah. Oh that’s great that track. On ‘Almost Blue’, by the way, Steve Nieve that string part on that- that’s 18 violas.

Wow. Gosh.

He wanted to write it for violas because he knew what top note that the violas could play so, anyway, we got 18 violas to do that.

You managed to get 18 viola players?

Yeah.

I’ll be quick now. I have to mention Band On The Run as well. You worked with Paul quite a lot post-Beatles as well and going off to Nigeria must have been one hell of an adventure.

Yeah. You can say that again. Well, it was monsoon time and all sorts of stuff and Ginger Baker thought we were going to his studio and we were doing it at EMI studio. And Paul got robbed, of course, as you know, with his demos and some of the material was written there. And the band split up the day before we left, so it was just Linda, Denny Laine and Paul. Then we went into the EMI studio there in Lagos and did what we could.

From your book, Paul McCartney’s talent of just instantly knocking off a song or recalling something or playing an instrument, really shines through.

Yeah. He’s a musician’s musician. John was the brash guy who, I think I said in the book, he’d accept some basic rhythm track 95 percent and Paul would always want the extra five or six percent to make it absolutely perfect. So, when we were working on those tracks, we were really aiming all the time for perfection and we didn’t do edits on our basic rhythm tracks either. If it was screwed up, or even a few bars from the end and the rest of it was good, we’d do another take. It wasn’t the rules at EMI that you actually did edits, believe it or not.

And I’ve got one final question. If there’s one particular song from THE SESSIONS show that you think works particularly well, what is that and why?

It’s got to be ‘A Day In The Life’. Most of them sound pretty close to the finished records that you’ve heard before but, definitely, ‘A Day In The Life’ because it’s amazing. Although John, in the middle, goes into that high, high voice after ‘Woke up, got out of bed’ and after the word ‘dream’, we use both voices. Both the Paul and the John on top of that, which makes it a lot louder. And the orchestral part sounds amazing. It’s just unbelievable, it really is.

And some people need to go to thesessionslive.com to find out where you are on tour. I’m definitely going to see it in Leeds as well, so I wish you all the best Geoff.

No, thank you. I’m going to say it’s like the finest Beatles concert – let’s call it a concert – you’ll ever see and hear, to be honest with you, because there’s nothing really to touch it and there never will be, I don’t think.

Is it ‘Hey Jude’ that you finish with?

Yeah, we do, yes.

That must be quite a bit of a sing-along moment on the show.

It was unbelievable in Dublin because, often when you do ‘Hey Jude’ at the end, a lot of people sort of want to leave to catch their transport home. But they started to leave and then just stood there and joined in. And they seemed mesmerized as well because, well, I said it before, they’re quite in awe of what they’re actually seeing and hearing because those records, their favourite Beatle records, have travelled with them all through their lives. They either got engaged or they got married at a certain record and it’s part of their life and then they’re sitting there watching them being performed as they know them – watching The Beatles – because they’re all dressed appropriately as they go through different albums and the way they used to dress and so forth. There’s a little bit of choreography with it. And all the movements of the microphones as well, on the stage, is all choreographed because microphones move between songs and so does the drum kit but the people that come on the stage, which represent the maintenance people at the time, with the white coats and so on, they actually move all the instruments around plus the drum kit, plus the microphones. So it’s all been choreographed and so those movements are the same every night, although it doesn’t look like it. It’s quite amazing.

It sounds fantastic and is there anything else? Any other projects that you’ve got ongoing Geoff or it’s mainly focused on THE SESSIONS at the minute?

It’s just on THE SESSIONS but I’m finishing an album off, because I live in Los Angeles, and I’m finishing an album off with a new guy I’ve got there and then I’m going to New Orleans for jazz week to do something for NARAS [National Academy of Recording Arts and Science], the GRAMMY people. And then they’ve opened a GRAMMY museum in Cleveland, I believe, at the end of that week – at the end of this month – at the museum in Cleveland. So they’re opening another GRAMMY museum there.

Fantastic. You’ve got three of those, I understand?

Four. I actually got a technical GRAMMY which was for breaking down barriers and building new frontiers.

Geoff, thank you so much for your time.

Okay great.

It’s been an honour. Much appreciated. Thank you so much.

Okay. Thank you. Bye-bye.

Postscript

On 5 July 2016 it was announced on Facebook:

“We just tried to bring you the best Beatle show ever staged…

Therefore, it is with the deepest regret that The Soundstage Theatre Company UK is announcing the cancellation of all currently scheduled performances of “THE SESSIONS – a LIVE re-staging of The Beatles at Abbey Road Studios”. With circumstances beyond their control and imagination, including financial disappointments, terrorism in Europe affecting ticket sales and future copyright issues, they are not in a position to continue with the remaining shows.

There were 5 magical performances, and everyone was exceptionally proud of this new show – a tremendous effort of world-class talent, and critically acclaimed by audiences and the world press.”

The show’s creator, Stig Egdren, posted a more extensive explanation on The Sessions website which has since been deleted but is now saved for posterity on archive.org.

Reading between the lines from what Stig said, the bureaucracy of clearing 60+ Beatles songs across multiple territories was likely to be prohibitively expensive and, potentially, impossible. Copyright laws distinguish between ‘covers’ bands and stage shows that include songs (musicals) but this was not necessarily appreciated by all involved. The simple concept of transforming Geoff’s book into a worldwide stage show was unfortunately doomed at birth.

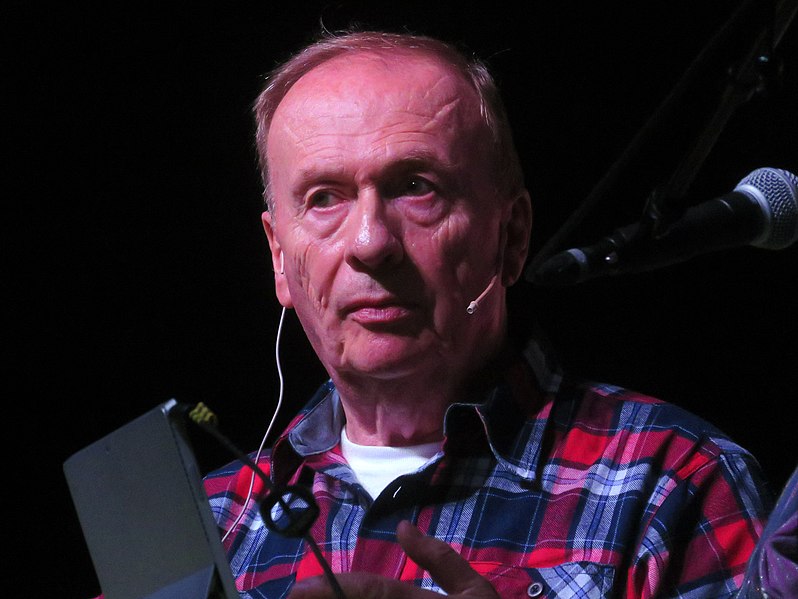

Emerick died from a heart attack on 2 October 2018, aged 72. On 3 October Paul McCartney wrote on his website:

“I first met Geoff when he was a young engineer working at Abbey Road Studios. He would grow to be the main engineer that we worked with on many of our Beatles tracks. He had a sense of humour that fitted well with our attitude to work in the studio and was always open to the many new ideas that we threw at him. He grew to understand what we liked to hear and developed all sorts of techniques to achieve this.

He would use a special microphone for the bass drum and played it strategically to achieve the sound that we asked him for. We spent many exciting hours in the studio and he never failed to come up with the goods. After The Beatles, I continued to work with him and our friendship grew to the point where when he got married to his beautiful wife Nicole, it was in the church close to where we lived in the country…

I’ll always remember him with great fondness and I know his work will be long remembered by connoisseurs of sound.

Lots of love Geoff, it was a privilege to know you.

Love

Paul”

Further information

Ken Scott on The Beatles White Album

Colin Blunstone and Rod Argent interviews

Bruce Thomas – Elvis Costello and The Attractions podcast

Acknowledgements

Transcript and extra research provided by Nigel Davis.