While Geoff Bridgford’s time as the Bee Gees’ drummer in the early 1970s solidified his place in music history, his journey didn’t end there. In Geoff’s conversation with Jason Barnard, he charts his beginnings with groups like Steve & The Board, The Groove and Tin Tin. We also explore his significant contributions to Bee Gees albums Two Years On and Trafalgar, topping the US singles charts and why he took the decision to leave the group at a time of huge success. Since then, he has embarked on a personal journey, exploring his own musical talents as a singer-songwriter. Join us as we uncover the remarkable story of Geoff Bridgford.

A huge welcome, Geoff.

Thanks, Jason. Nice to be here.

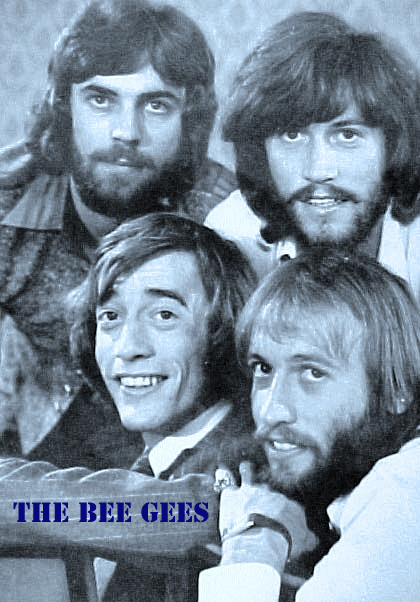

We’ll be focusing on The Bee Gees a bit later but am I right, in terms of your status with the Bee Gees, that you were the last non Gibb brother to be an official Bee Gee?

Yeah, that’s right. After I left, they became three brothers, and in a way, it was always just meant to be, as history will show that it really was just the three brothers who were the Bee Gees. Even in the early days, I think that they wanted to have a band, they wanted to sort of be like The Beatles and all that stuff, but really had been doing it for a decade or so before they arrived in London.

But I was quite surprised when they asked me to become a member of the band, to be honest. It was a bit of a shock.

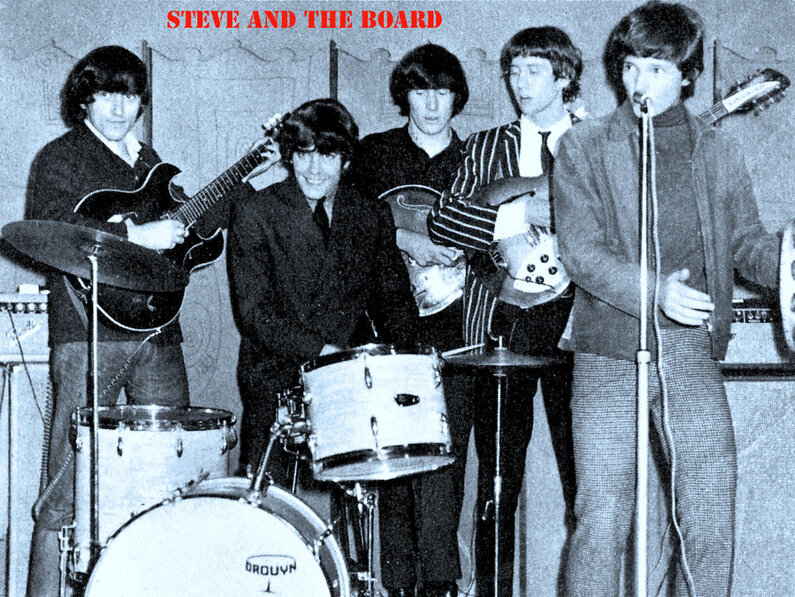

What I have realised in Australian and New Zealand groups is a lot of you knew each other, and you went in and out of bands. There were often times when groups would come over to London, England as well, and you’re no exception. Interestingly, am I right that you took Colin Petersen’s place in Steve & The Board?

That’s right, yeah. Colin was leaving the group to go to England, and I can’t remember what the situation was really something to do with an acting career as well, because he’d done a film in Australia. I’d been playing in a couple of local bands and had a job working in the city, in Melbourne as an office boy for an advertising company. I used to go to a record store in Melbourne called Allans Music every lunchtime. I befriended some of the girls who worked in the store, and in those days, they had listening booths where you could go and listen to the latest singles and latest music that was coming out.

And Allans Music store is where I purchased a drum kit. So it was just a place that I would regularly visit. And I remember one day, one of the girls behind the counter said, ‘You’re a drummer, right?’

And I said, ‘Yeah’. And she said, ‘Well, what are you wanting to do as a drummer?’ I said, ‘Well, I’d like to be a full time musician’. And she said, ‘Go to this lunchtime club’. It was just a couple of streets up. It was called 10th Avenue. And she said, ‘I was there today and there’s this group called Steve & The Board. And the singer said they were looking for a drummer, and if anybody knew a drummer, let them know that we’re looking for a drummer.’

And she said, as a matter of fact, ‘They got a record that’s number four in the Melbourne charts at the moment called The Giggle-Eyed Goo’. And I said, what a strange title for the song. And I said, give us a listen.

So she played it for me and it was an unusual song, but it really definitely had something and something that had made it popular. It was the guitarist, the sound of the guitars that really knocked me out.

They were kind of punky and rocky, and I thought I’d go up and check them out. So I went up there and walked in and the place was full and the girls were screaming. And during a break, I went to the little backstage area they had and I said, ‘Hey, guys, I heard that you’re looking for a drummer’.

And they said, ‘Yeah, we are and Colin, our drummer at the moment, is going to be leaving at the end of this week’. And I said, ‘Well, I’m a drummer and I’d like to have a shot at it’. So Steve said, ‘Okay, we’ll get you up in the next set’.

So they got me up in the next set and we played Gloria by Them. It was the song that everybody played and all the audience knew it.

So that was an easy one to pull out to play. And at the end of that, Steve said to the audience, ‘This guy was just auditioning to be our new drummer. What does everybody reckon?’ And everybody sort of screamed and Steve just turned around and said, ‘Okay, mate, you’re in’. And that’s how it happened. That’s how I came to join Steve & The Board. And things changed for me at that point in time.

You were discussing before about the interrelationship with musicians, but the other aspect is the interrelationship with members of the Bee Gees as well. Now I’m Older by Steve & The Board, I think, was that the first song that you were on?

Yeah, that was the first song I recorded with Steve & The Board. They were signed because of the relationship that Steve had with his father, Nat Kipner, who wrote The Giggle-Eyed Goo. He organised himself to have a record label called Spin Records. And he’d actually signed up the Bee Gees to Spin Records.

And Steve & The Board were signed as well so we were stablemates. And I vaguely recall whenever we were in Sydney, we’d always bump into the Bee Gees and I remember going to the house where they lived in Sydney and hanging out with them although I can’t say we were close friends.

But on that session with Now I’m Older, Maurice Gibb was at the studio the day we recorded that and he sang in the bridge of that song. I think that Steve and Carl Groszmann, had more of a relationship with the brothers prior to me joining Steve & The Board because the Board had been going about a year or something before I got involved.

And the Bee Gees had actually recorded one of Carl’s songs. He was the guitar player in Steve & The Board. And Steve & The Board had recorded a Bee Gees song called Little Miss Rhythm & Blues for the Steve & The Board album.

I know that I didn’t play on the Steve & The Board album but they still hadn’t shot the photo for the cover for the album. So Colin left and then we did a photo session and I’m on the front cover, but I didn’t play on that album. I just played on the couple of singles that followed the release of that album. That’s sort of where the tie was with the Bee Gees. It was just a connection that had happened through Nat Kipner and his involvement with EMI and Spin Records.

There was a lot of songwriting talent in the band. You’ve got Carl Groszmann who later wrote Down The Dustpipe, a big hit for Status Quo. You’ve also got Steve Kipner who wrote for Olivia Newton John and much more.

Yeah, they both were brilliant songwriters. It was a great situation to get in and play with those guys, because basically I’d been playing in cover bands before that. Steve & The Board were a totally original band and it was such a good influence.

Carl went on to be signed up by Ringo Starr for Ring-O Records and wrote a single for Ringo, which he released plus Down The Dustpipe for the Status Quo band, which was a great song. And Steve just ended up being an incredibly successful songwriter, and he encouraged me to write songs and to take that look at things musically, especially when I got involved in Tin Tin later on with Steve and Carl. But, yeah, they both ended up being very successful songwriters in their own right, those two guys.

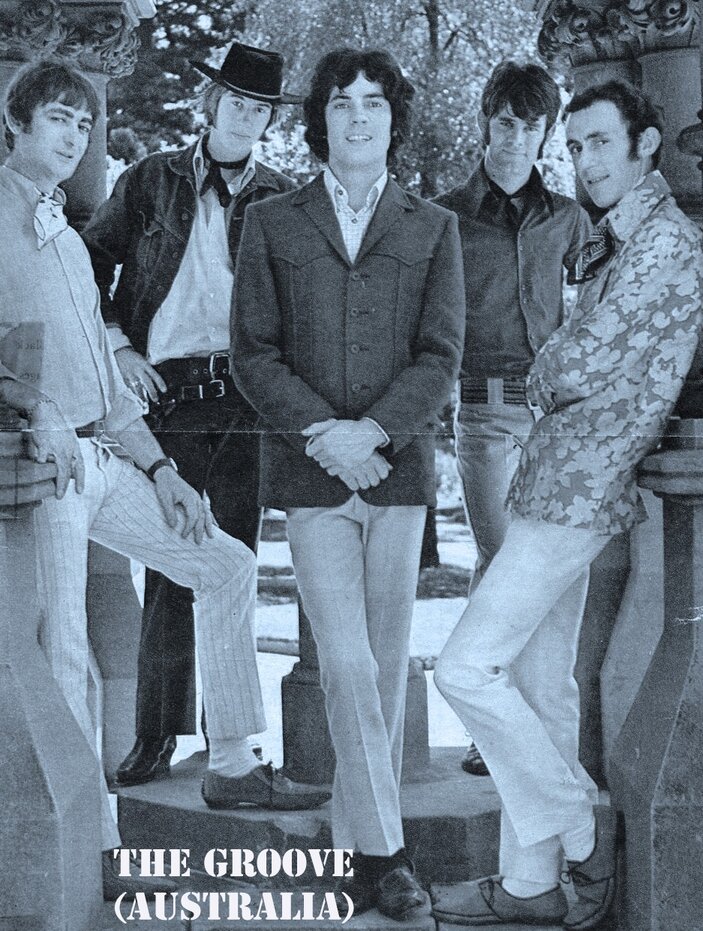

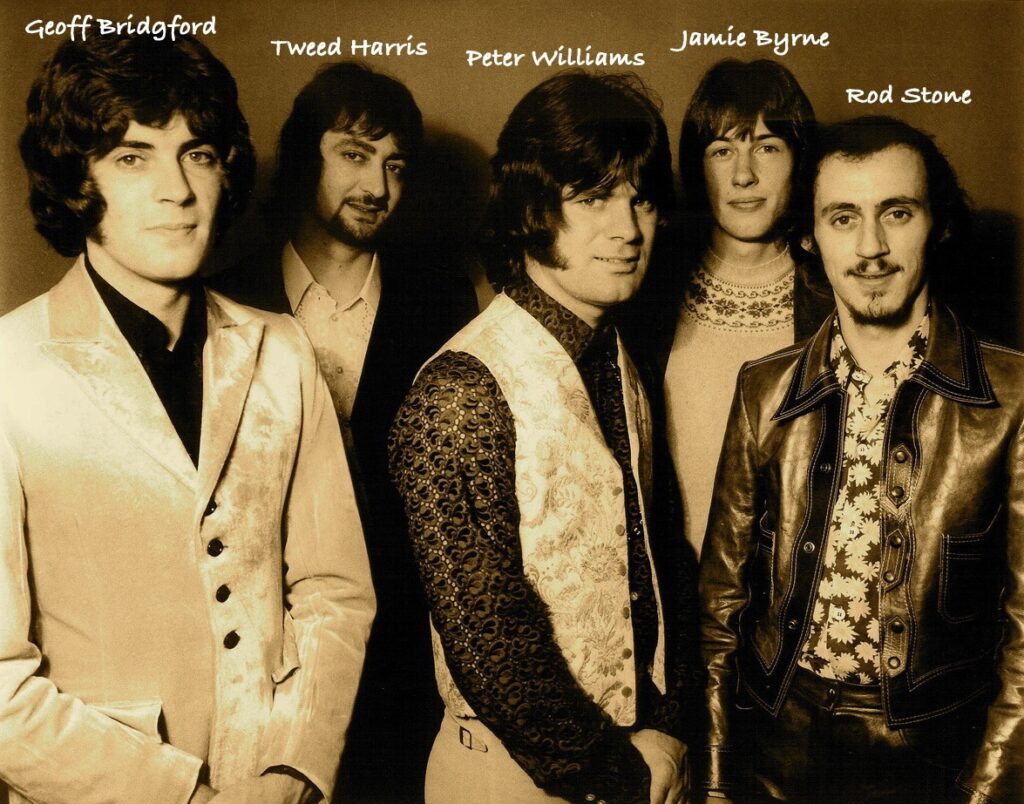

I also referred to the new compilation of The Groove. So tell us about the formation of that group.

Well, Steve & The Board had been going about a year. It was just one of those serendipitous moments for me – Steve & The Board were living together in a little house in Melbourne. And the day Steve & The Board broke up, I got a knock on the door and it was a guy called Garry Spry, who was a manager. He was managing what was going to be happening with The Groove and he’d formed this band called The Groove with Tweed Harris. He was a keyboard player from Adelaide who had been playing in a quite successful jazz soul outfit around The Traps in Melbourne called The Clefs. And Peter Williams, a singer from New Zealand who had been playing.

And Rod Stone, a guitarist from a New Zealand band called The Librettos, who were pretty popular. But those three guys turned up with Garry Spy at my door and said, ‘We’re looking for a drummer and we’re going to form a supergroup’.

And they said, ‘We’re going to be the biggest band in the country in six months’ time. Do you want to get in?’ So I said, ‘Sure, why not?’ So that was my introduction to the boys in The Groove and the next day we were rehearsing.

The first batch of singles by The Groove, there were quite a few soul covers. Soothe Me was one of the big early hits for the group. So was that something that you and the band really aimed for, a more soulful sound?

Yeah, that was at the time in Melbourne from the British Music Invasion that came with the Beatles and the Stones. What came with them was all this influences of the American soul, blues – black R&B music.

The Beatles and The Stones were so into that, so they unearthed this whole genre, this whole mode of music. And the boys in the group, Peter Williams in Max Merritt & The Meteors, they’d been doing a sort of a soulful scene, and Tweed In The Clefs had been doing a very similar sort of thing.

But it was a massively inspiring introduction for me was music from the Stax and Motown labels. To be doing songs released by the Isley Brothers and Sam Cooke, I think, did suit me. And we ended up doing some amazing songs that took me into a whole new genre of music and a style of playing which made the group incredibly popular. They were a strong, original band at that point in time but we made it on the success of riding on the tails and on the shoulders of these other great artists from America, really.

It was an interesting phase for me because I remember Tweed Harris, he was sort of into the sort of semi jazz, sort of style of soul and R&B kind of thing. And I think there’s a track that he actually sang on the Groove album called Got My Mojo Working, a sort of semi-jazz instrumental. He was really into the organ and that was also part of the Groove’s style.

But I remember in the first few rehearsals that we did with the Groove in this little club in Melbourne and the bass player was a guy called Jamie, James Byrne who was playing in a band called the Running, Jumping, Standing Still. One of the most important things that Tweed said is that we gotta get this Motown thing down. And he used to keep us after rehearsal and he used to say the most important thing is just to get into the feel. You don’t have to be clever, you don’t have to be technically fancy or this or that said, you just got to find the groove and lock in and sit on it and learn to move a little bit left, a little bit right with it.

And for about a half an hour after every rehearsal. We used to sit on this Motown feel, which was sort of a powerful groove. It was a common, general sort of style of the Motown sound. There’s many, many songs that were done with this sort of style. And the simplicity in finding something in some of the music that I eventually just totally fell in love with.

The Group had quite a run of hit singles in Australia, including What Is Soul. By 1968, you were in the top echelons of great groups like the Twilights and Masters Apprentices.

Well, they were right when they came to my door and asked me to join and said, ‘We’re going to be the biggest band in the country in six months’ time’.

And we were. And then we entered this national battle of the bands competition called Hoadley’s Battle of the Sounds. We won in 1968 and part of the prize was a trip to England. And we already were signed to EMI, but another part of the trip was recording sessions at Abbey Road. So, yeah, the group became massively huge and we just toured nonstop for a couple of years and became very, very successful. We only had one album and four or five singles.

I recall that The Fourmyula were a New Zealand group signed to Parlophone and then ended up coming over. What was the relationship if you were assigned to the likes of EMI over in Australia or New Zealand, and the company over in England. Was there much contact between the two, or was it almost like starting again when you got to England?

No, there was a familiarity in those days. I think EMI was EMI International as far as Australia went as well. The guy who produced our album was an Australian guy called David Mackay in Australia. He ended up going to England and producing for EMI in England. And I remember that when we ended up in England he produced some of our stuff at Abbey Road as well. So there just seemed to be a tie in. I’m a little bit out of the loop of the information about the record company stuff but there just must have been a natural tie up between the companies.

The Wind was released as a single by The Groove. That was a different direction that seemed to be a bit more in the spirit of what was going on in England at the time. It was a bit more of a rock sound.

Yeah, perhaps. I think that we’d run our course with the soul thing when we realised there were so many good soul bands in London and we changed direction pretty quickly.

At one point we all became pretty heavily influenced by the American group The Band, and we made a record. After the group broke up, we made an album with a new name called Eureka Stockade and that was very ‘Band’ influence, but with The Wind, one of the key things about The Groove was that Peter was a pretty dynamic singer and he was looking for a little bit more than just the soul genre, the R&B genre.

And also Tweed was such a really incredible organ player and I think he was looking for something too outside of the mainstream of the soul R&B organ. And we all loved what Procol Harum did with A Whiter Shade of Pale.

When I listen to the track, I think it was a little bit of an influence to do something that was more orientated, pop, rock wise, to let Tweed have a bit of a go. The organ is pretty dominant. It was a great song and it was a great direction for the band to go in. It was an experiment. Pity that it didn’t create a bit more of a wave that we could have kept on going, but we were sort of going in a bit of a different direction at that point, we were heading a little bit more down a sort of a country rock lane.

The new compilation, the second CD has got the whole of the unreleased Eureka Stockade album as well. So that shows another side to the group.

Yeah, I distinctly remember that in 1969, before we left, we did a big show with The Twilights, who had won the national battle of the bands a couple of years before us and had gone to England. And it didn’t work out for them either. And they came back to Australia, but they were going to be doing this big concert with us and we got together at the hotel in Sydney before we were going to do this show.

And I remember sitting down with Terry Britten, who was the guitar player in The Twilights, who also went on to be quite a successful songwriter, writing for Tina Turner and stuff. But I remember the guys in the Twilights, it was the first time I’d smoked pot marijuana. So we all rolled up and we all started smoking and they said, ‘Have you heard of this group called The Band?’ And I said, ‘No’ it completely blew us all away.

Levon Helm in The Band became my biggest influence of all time as a drummer, they became the biggest influence. I think that swept through The Groove when we got to London. And so on the Eureka Stockade album it’s got the soul influences that lingered over from the Groove, but it’s got a very strong, pronounced presence of trying to be a little bit being influenced by The Band, actually. It was a good album. Everybody threw in songs. It was an original album and everybody shared. It was the first song I’d written that was ever recorded, which wasn’t such a great song, called I Aint Living on Easy Street, I think, and Peter sang, I didn’t sing on any of these songs. But it was a great opportunity to start to dig into that creative side of writing capabilities of The Groove.

And everybody was inspiring. James Byrne, the bass player in the Groove, was especially a strong influence in getting me writing and we wrote quite a few songs together, actually, which was fun. But, yeah, it was a little bit too little, too late by the time we got to the Eureka Stockade album and I think there might have been a single, but the album never came out.

It was inspiring for us, but I don’t think it was quite strong enough in the marketplace to make a dent. We were up against too many. Music was exploding. There were hundreds of bands.

Was the group Tin Tin a progression from playing with Maurice? Or was it just that you were all friends and Tin Tin evolved separately?

Once again, it’s slightly sketchy. When the Groove broke up, I connected with Steve Kipner from Steve & The Board who had arrived in London. We started hanging out and he had mentioned that he was starting the group.

He was with Steve Groves, who had come from a Melbourne band called The Kinetics. The two Steve’s were in London and a few things had evolved, but they started out as Steve and Stevie. There was a connection with the Bee Gees and with Maurice, and because of the history that Steve had had with his father Nat and the Bee Gees in Australia.

So there was a connection that happened in London with Steve Kipner and the Bee Gees. Once again, Maurice was maybe looking to produce people and I think when Steve and Stevie didn’t work out, they became Tin Tin.

And at that time The Groove had broken up and I was looking for something else to do and was hanging out with Steve in London. He said, ‘Why don’t you get involved with Tin Tin?’ And at that point, the Bee Gees had broken up and Maurice was recording a solo album. I remember getting a call from him to say, ‘I heard that you are in London. Do you want to come down and do some recording with me?’ So I ended up recording a whole solo album with Maurice which was called The Loner and I don’t think it was ever released. But that was the tie up with getting involved with Tin Tin, which led to Maurice hearing about me being in London and he was looking for a drummer.

And it was sort of interesting because Colin, who I replaced in Steve & The Board, had become a Bee Gee. And then for some reason or another, he left. After Robin left, from my memory, I got called up to come in. Maurice called me up to finish off recording Cucumber Castle, but I sort of vaguely remember playing on a few tracks on that. But I’m not in any credit or anything to do with that, so I can’t really say what I remember clearly about that, but I got involved, that’s for sure.

But that led on to working with Maurice and it led on to working with Tin Tin, which Maurice was producing with his brother in law, Billy Lawrie. So one thing led to another at that point in time. It was a great time to get involved with Maurice Gibb and Steve Kipner again, and Steve Groves, and also Carl Groszmann got involved with Tin Tin again and he was another member of Steve & The Board. So it was a brother thing. It was a really nice time for me.

Tin Tin recorded at least two albums and there were singles and there was some success as well. Tin Tin’s material is consistently strong and so you’ve singled out The Cavalry’s Coming from the Astral Taxi album.

It’s a beautiful song. I had nothing to do with the first Tin Tin album. Steve played most of the drums on that. I think they just got lost in the wash at one point, just with RSO, their record company, and management at Abigail, their publishing company, just things sort of started to get a little bit lost in the maze of what was going on.

But I remember The Cavalry’s Coming, I remember as much as it’s got no drums on it, apart from the bass drum. I remember just being taken by the song. There was a great single released by Tin Tin that Carl Groszmann wrote with the two Steve’s called Shana, which was amazing.

Tin Tin was a very creative period for me. I was encouraged immensely by Steve Kipner to start writing songs and I actually had an A-side released. It was my first vocal ever, I think, on any sort of record. A song called Come On Over Again. Once again, it wasn’t a very good song, but The Cavalry’s Coming is a lovely song and it still stands up today to me as I listen to it now.

We do move into the Bee Gees. Some sources talk about Robin and Maurice getting together and playing with you in the middle of 1970 before Barry was on board. Do you recall that period?

Vaguely, I just got pretty involved with Maurice and on his album and that sort of probably slipped into doing a few things with Robin who had decided to come back and get involved again with the Bee Gees. I can’t really recall clearly sessions with Robin and Maurice together. I just recall when the Bee Gees decided to reform. I was just sitting in the drum seat. I’d been doing a lot of recording with Maurice especially. And so when it came around that they wanted to go back into the studios as the Bee Gees. It was like I was just there in the right place at the right time, basically.

I remember the recording of Lonely Days. It was just Maurice and me and I think it was Barry doing the guide vocal. A lot of the songs were just recorded with either me and Barry or me and Maurice on piano or Barry on guitar. And that was pretty much the basic track from memory. Maurice pretty much always overdubbed his bass parts and Lonely Days was a track that happened so quickly. I think that’s the third take, maybe even the second take.

I remember thinking it’s a little bit out of sorts. I remember saying, ‘Can we do it again a couple more times?’ I was just sort of getting used to it – when I listen to it – I’m still a little bit jumpy about the fact that I wish I’d had a chance to record it a couple more times with them. I would have liked to have settled in a little bit at the end, but Barry, he blew the roof off it with his Lonely Days section at the end. It sounded like John Lennon was in the room.

It was incredible. Very inspiring session. Lonely Days was an unusual song, a beautiful song. I love the change of the tempos and the rocking end to it. Once again, it just shows the virtuoso and the prolificness of the Bee Gees talent. They are amazing songwriters. They were still finding their way personally and creatively on Two Years On. It was still an unusual time for them to be back together as brothers, sort of navigating their way.

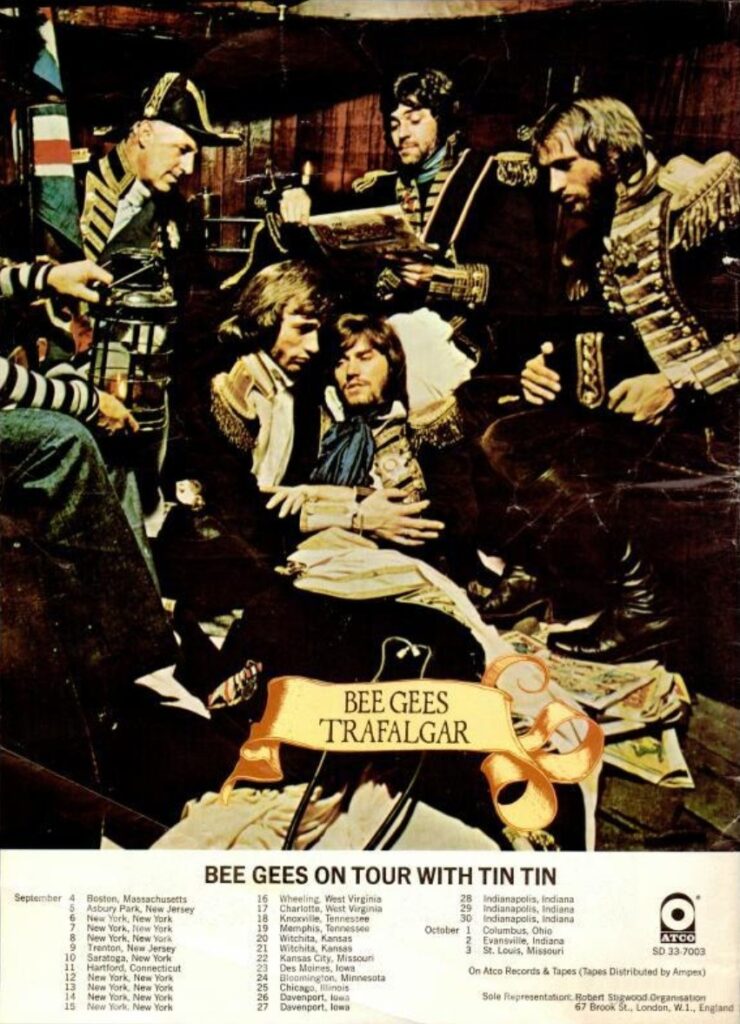

I was just a session player on Two Years On. It wasn’t until we went to America, touring and promoting the Two Years On album and the Lonely Days single, which became a massive hit. I think it got number three or something.

It wasn’t until we got back from that American tour that we started recording on the Trafalgar album. And I remember the brothers in IBC Studios came up to me and said, ‘Do you want to become a Bee Gee?’ So it was during the Trafalgar album that I was asked to join the band as an official member, which was a shock, a surprise, really.

I was pretty happy being in Tin Tin. I had something in Tin Tin that the Bee Gees had in the Bee Gees. They were brothers that had been doing what they were doing for a decade before I came on board. And it was an unusual time for me to be asked to join the Bee Gees.

I was very friendly with Carl, Steve Kipner, Steve Groves and John Vallins in Tin Tin, and we all felt like brothers. We were all getting ready to roll. Then I was asked to join the Bee Gees and then Tin Tin were going to be the support on the second tour to America to promote Broken Heart and the Trafalgar album.

And I was told that I was just going to be playing in the Bee Gees. I wasn’t going to be able to play in the support band and it was a little bit disappointing at the time, it was a surprise. I remember talking to Steve Kipner, saying, ‘What do you think? They’re asking me to join them. I want to be with Tin Tin.’ And he said, ‘Are you kidding me? The Bee Gees are one of the biggest bands in the world and you’re being asked to join one of the biggest bands in the world.’ I’m like, well, ‘Yeah, but still.’ Anyway, history as it turned out, the three brothers were meant to be. I wasn’t meant to be.

There wasn’t much time before you were back in the studio, very late 1970. One of the highlights of Trafalgar, which doesn’t get heard as much as it should, is Israel.

I remember thinking it was a sort of a strange sort of song. I’m not quite sure what Barry was thinking about with Israel. The only thing I can think is that so many Jews were persecuted in the Second World War. But the interesting thing about Israel, which is an interesting thing about a couple of the tracks on the Trafalgar album, is that Barry made the lyrics up on the spot.

He had no notes to Israel before he did the vocal. He sang the first thing that came into his head. And I remember we really rocked the track. Really rocked. And it was a pretty spontaneous take. And the further we got into it, the more we belted it out.

Again, it was me and Barry would have been playing guitar, Maurice could have been on the piano. It was a very simple sort of instrumentation, the way the Bee Gees used to record. Like I said, I always sort of remember Maurice over dubbing bass and the songs were always recorded either with me with Maurice on piano and Barry on guitar.

It was maybe unusual for Barry and Maurice to be playing together with the drummer, which was me. And I’d always come back, usually on the orchestral sessions and listen to the tracks after the orchestra would go down.

And then it was like, ‘Wow. It was like a fully blown production. But, yeah, Israel is one of my favourite tracks on Trafalgar simply because it’s incredibly authentic, recorded in the moment. I don’t think there was a second take of Israel. I know there wasn’t a second take on the vocal. I loved Barry in those days. He was like Otis Redding, his soulful rock, soulful voice. He was, without a doubt, the best singer I played drums for. I’m not taking Robin out of the equation here. There’s no one like Robin Gibb when it comes to vocals. But Trafalgar was once again an interesting journey. It was a very experimental album.

They were sort of wanting to break away from some of the stuff they’d done on their albums prior to Trafalgar. And the Two Years On album was really they were treading on eggshells a little bit between each other during that. They were getting to know each other again and familiarised their closeness and love for each other as brothers. But the Trafalgar album, everyone was getting a chance.

Maurice was getting a chance to sing, which he didn’t usually get much of a chance to do. And his musicianship, to me, blew my mind. He was a brilliant musician. Maurice Gibb, he was one guy, he could come into a studio, he could pull a set of strings off a guitar he could start putting strings on, and he didn’t need to find a tuner to find the tone. He could just find it. On the Trafalgar album, everything you hear is Maurice Gibb, some guitar playing from Barry. And I think Alan Kendall, I think he started getting involved. But Maurice took the lion’s share of the musicality on the Trafalgar album and most of the Two Years On album as well. I have a lot of respect for Maurice Gibb as a musician.

Another one that’s like that was Don’t Wanna To Live Inside Myself. That was also another one of my favourites. That was a real experimental one, where it was like Barry decided he was going to just sing some stuff. He had a few notes, but he was just going to sing the first thing that came into his head. But it was a very interesting lyric. It’s very introspective, and that was nice.

But when we were working on the song, I was like, what do I play? And Maurice was like, ‘You just play whatever you want to play’, and it ended up being a bit of a drum fest. But I have some good memories of the Trafalgar album. We really were a four piece band, we really were feeding off each other, and I never really had got involved in the vocals or even the co-writing side of the Bee Gees, but as a drummer, I’m proud of my input on the Trafalgar album.

And this is a period where the Bee Gees were having more success in the US than they were in the UK. A US number one with How Can You Mend A Broken Heart. That must have been incredibly exciting.

Oh, it was. It was incredibly exciting for everybody. I think that Lonely Days did pretty well and I can’t remember what singles came out. The interesting thing about How Can You Mend A Broken Heart was that it didn’t even chart in England.

It brought out something that the Bee Gees had. Barry had this real love for country music. I remember recording Broken Heart with Barry and he just said, I got this song, there’s a country singer, I’m not sure, I don’t think it’s Jim Reeves, it was somebody Reeves, and Barry was a big fan of. And he mentioned that at the time of the recording of Broken Heart.

But from memory, he and I just did it together, guitar and drums. The original take, Maurice could have been on bass, but I don’t think he was on piano. But it’s a masterful track. One of the favourite things I ever did was the Bee Gees. And yet, to get to number one, I think that tour, after it went to number one and I think it was either in Nashville or Memphis on the tour, it was the biggest show we played, a big stadium. I think it was 30,000. And I don’t think the Bee Gees had ever seen any success like that in America until Broken Heart. It was either in Memphis or Nashville. They sold out two nights.

And I remember all the country people coming backstage and then we went to this huge party at Roy Orbison’s house and all the country people were there, all the country stars, the country stars. Of course, everybody was a little bit out of it, including me. So I can’t really clearly remember but I remember they really tapped into one of the biggest musical markets in the world, the country music market in America.

Going back to Australia including the July 1971 show at Festival Hall, Melbourne must have been a really fantastic moment for you all.

Yeah, well, the first tour, which I think was in early 1971, before Broken Heart. It was the first time they’d been back since leaving in 67. And it was the first time I’d been back since leaving in 69.And it was a homecoming of sorts for them, really, and it was definitely a homecoming for me. But it was an amazing tour. I think we sold out a couple nights in Festival Hall in Melbourne and I remember being so nervous.

I was shaking terribly on the drum kit. My parents were in the audience, my relatives and my brother and my friends, and everyone was there and it was a real good moment for the brothers. Going back to Australia after really becoming huge international stars.

I remember the press conferences at the hotel in Melbourne with my parents there. They were so proud and, yeah, it was an unusual experience. When I look back at 64, 65, and some of the little bands I played in, Steve & The Board, and then The Groove and then going overseas and coming back as a member of one of the biggest bands in the world. It was a trip, surreal, really.

My World might have been the last single that was released when you were still with the group, is that right?

Yeah, I think so. I think a couple came out after I left. I think Alive was the last single that was released by the Bee Gees that I played on. But My World stands out as one because we actually made a video clip which is available online, and I’m in that.

It must have been early 1972 when you left. What was going on in that period that led to you leaving. Do you recall?

It was a pretty trippy time to join the brothers when I did. Robin had left for his own personal reasons, and then when they came back together again, there was a lot of sort of shuffling going on between them.

They were finding their own space and time as individuals, but they all were living the high lifestyle. They all had big houses, they all had Rolls Royces, and they were successful musicians in their own right. And I think for Robin, he was a bit disenchanted after I Started A Joke and Massachusetts. I think he wanted to be a little bit more inclusive in the lead vocal aspect of the band.

It’s no secret that everyone was involved in drugs and alcohol big time. Everybody had problems with them. Maurice, Robin and Barry, I’ve heard them all talk about it, so it’s not like I need to say anything about how it was, it was a topsy turvy situation for everybody.

And even through the tours, it was still topsy turvy. They were still gravitating towards getting to know each other and the success was a little bit hit and miss. As much as Broken Heart was a massive hit, they were still sort of finding ground with being brothers again and on tour.

With Robin we had to cancel or Robin didn’t show for a couple of gigs because of his drug problems. Maurice was very difficult to deal with because of his alcohol problems. What can happen with an alcoholic is when people drink too much, they can become another person. And Maurice became another person when he drank too much. And as much as I loved them all, they became difficult to deal with on one level. And my behavioural patterns were also affected by drugs and alcohol.

And before I joined the Bee Gees I’d married and had a wife and a daughter. And during the Bee Gees things had become really chaotic. Travelling internationally and I think these day’s people term it as having mental health problems.

I started having problems because of my own drug and alcohol intake. And I left my wife, left my child and flying women around the world and living this rather strange lifestyle. And all of a sudden it came to the head after the second American tour and the second Australian tour and I collapsed in New Zealand and didn’t know who I was anymore.

I lost touch with myself and I needed to retreat. I needed to back away from that lifestyle. And it wasn’t so much anymore. I wasn’t so much looking at the fact that I was playing in this huge band.

I just needed help and I wanted to get back to my wife and child again. And so I decided the only way to do that was to pull the plug on the lifestyle I was living and make a change. And I remember being influenced by The Beatles and by their search for their own inner peace, especially George Harrison.

And I remember their involvement in the Indian spiritual side of finding inner peace. And I became interested in that even before the Bee Gees. And I ended up getting a mantra. And I remember one of the last shows I did with the Bee Gees would have been early February in February 1972, I think it was Holland.

We were doing a show with the Beach Boys and Johnny Cash. It was leading up to doing a short tour. We were going to be doing a concert in Rome. To sit back and watch The Beach Boys was incredible. Anyway, I pulled Carl Wilson, Alan Jardine and Mike Love aside because they’d all been meditating. They’d all been to India, and been to the ashram with The Beatles. And I remember pulling them aside and saying, ‘What was it like? What’s meditation like? And they just said, ‘It’s really cool, everything’s good, we’re getting a lot of peace, getting a lot of benefit from it’.

So I started finding myself becoming interested in having a go, like perceiving that world and seeing what could come of it. And by the time I got to Italy, after that show in Holland, I’d become pretty crazy, pretty freaked out.

I needed help really, in the same way the brothers needed help at some point. And I thought that the best thing I could do was to stop, leave the band and find some sanity somehow in my life, which had become pretty insane.

And so I decided that maybe I’d try and follow a spiritual lifestyle of some kind for a little while and see how that panned out. Actually, I remember on the way back from Rome, we were on the plane and I said to Barry, ‘It’s just become really difficult, Barry. I’m finding myself having a difficult time.’ I think I’d seen certain aspects of what it was like to become an incredibly successful person, to have a first class lifestyle, hit records, number one in America. I think I’m the first Australian musician to get a number one in America. It just sort of made me feel a little bit crazy. I needed to break away from it. It was one of the best things that I’ve done in my life.

When I look at some of the Bee Gee covers and albums and the music that followed, I’m just not in that picture. It was good to get back with my wife and child and it solidified a bit of sanity in my life to proceed from what happened from there.

So you went back to Australia, you did release material in the mid to late 70s. So talk about that period and how you gathered that material together and what was happening.

After I left the Bee Gees in early 1972, I took a hiatus away from the mainstream pop, rock and roll world. I lost interest in the fact that you should be somebody, because when I was leaving the Bee Gees, to be honest, Robert Stigwood, said they didn’t want me to leave, and they thought it was money. And Robert sent a limo for me, and invited me out to his house and sat down with me and said, ‘We want to put you on a full royalty. The boys want you to stay’. These are literally his words, he said, ‘You’d be a millionaire in six months. I’ll put 25,000 pounds cash on the table right now’. [laughs] The classic line was, ‘It’s not the money, Robert.’ I just needed to get out of the situation.

So I went on a bit of a hiatus and I did go to India. I did stay in an ashram. I did get involved in meditation, and that carried over for the next couple of years of my life. I got involved with some other musicians, did some underground projects. I started to get involved in writing a little bit more seriously, taking that on, thinking it was something I wanted to do, thinking perhaps I could sing, perhaps I’d become a solo artist and did a few demos here and there.

Anyway, I came to the attention of a small time label in Melbourne, Australia, called Indigo Records, and they’d heard a few demos that I’d done and wanted me to make an album. So I started recording. And some of the songs I didn’t have enough strong songs of my own to record, so it was a couple of musician mates I was friendly with, and one of them was Carl Groszmann from Tin Tin. I recorded a song of his, and another one was a budding singer songwriter girl called Kim O’Leary, who I befriended, and to this day I live with her, and she wrote a couple of songs, which I recorded.

One of the songs was Wild Night and it was going to become a single and so there was a video clip made of it, but the record company went bust and so I sort of went down the tube with them. The album that I recorded was never released, but a few video clips were made and there’s a couple of videos online on my YouTube channel.

But Wild Night is just such a great song. I think it’s going to come out on a best of Geoff Bridgford down the line. It was a good take and I recorded it with some of my best mates. Lindsay Field on vocals and guitar. And Kim O’Leary. Ross Hannaford, a guitar player from a very successful, incredible band called Daddy Cool, who were the Australian version of the Rolling Stones. And he sadly passed away a couple of years ago. And Joe Creighton, an amazing bass player. So those people that I played with on Wild Night, it was recorded in 1976 in Melbourne. I’m still close friends with all these people.

You played with Mark Gillespie, including his album Ring of Truth. I think we’re in the early to mid 80s now.

Yeah, 1982 or 83. In 1977 I left Australia and did a whole bunch of stuff around the world musically, bits and pieces. It was mainly underground, nothing that was really high profile in the music business. But I came back to Australia in 82 and started hanging out with Ross Hannaford and Joe Creighton again, who I’d been playing with in my underground world.

And they were picked up by this Australian singer songwriter called Mark Gillespie. He was sort of the Bob Dylan Lou Reed of Australia. He released a couple of albums in the early eighties and was really quite famous and successful.

And when I came back to Australia in 82, Joe and Ross were playing for him. So he was going out on the road and I got asked to play drums for him. So that’s how I got involved with Mark. I was really surprised. He had these huge audiences in the pubs and clubs that I played with him and we supported Joe Cocker. In a Mark Gillespie gig, you’d see members of Australian bands like INXS and Midnight Oil. You’d see these guys turning up in the audience to check Mark out.

I didn’t play on his first two albums, but I played on his third album called Ring Of Truth, which was just me and Mark and a few high profile backing vocalists Renee Geyer, Venetta Fields and Lisa Bade.

It was a great album. It never really saw the true light of day. He found it difficult to deal with the success that came his way. I remember one day he was sitting in a hotel lobby waiting for Rolling Stone to come and do an interview with him. He decided there in the moment that he didn’t want to do it anymore. He ended up going to Bangladesh and getting involved in humanitarian work, helping people in poverty, helping children in schools, and that’s where he ended up dying a few years ago.

He passed away there as a charity worker, but he was a great singer songwriter. He had all the stuff that people like Bob Dylan, Van Morrison, Lou Reed had. He had it.

So by the late 80s, you did start to focus more on writing your own material and recording it. And Easy to Love comes from that period, doesn’t it?

Yeah. After Mark Gillespie, I’d done quite a lot of tours with him. I also did some touring with a massively successful Australian band called Goanna. And when I was on tour with Goanna in 83, we were touring around Australia. And we came to a place called Byron Bay, where we were doing a tour which has become a very successful, well known location.

And in 83, when I was on tour with Goanna, but I remember going to Byron Bay and getting out of the car we were in and standing on the foreshore and looking out to the beach, I just had this epiphany that this is where I needed to be, this is the place I needed to live.

And in 84 I moved to Byron Bay and pretty much gave up everything. I gave up all music, playing music. I decided I wasn’t going to play drums anymore, I wasn’t going to tour anymore. I needed a long break.

I hadn’t stopped since leaving Australia in 1969. I said I was going to learn how to surf and learn how to cook and just become a housebody, which I sort of did. But I got lured back into playing by a local band, Byron Bay band called Hip Pocket.

And then Mark Gillespie wanted to do another tour in 86, I think it was. So I went out and did a bit of stuff in 86. But when I came back to Byron Bay, I once again decided I wasn’t going to do that anymore as a touring drummer.

And I decided to have a go at writing songs. And I hooked up with an Australian artist, painter, poet, writer, Suzie Speirs, and we started writing some songs together. Easy To Love was one of those songs that we wrote and it got recorded in Melbourne. It’s one take, it’s a live vocal. It was the guide vocal to the first take of the song. So I’m proud of that.

I started a band called Modern Life with a drummer and a bass player, and we played a gig for Greenpeace. I got involved in the environmental movement, the Wilderness Society and Greenpeace, and we were doing fundraisers. We did some fundraisers in Melbourne with Crowded House. To this day, the best band I’ve seen live on stage ever. And during one of these nights with Crowded House – the front of house engineer came up and said, ‘You guys are so good. Have you ever done any recording? And I said, no, we’ve never done any recording as Modern Life.’ He said, ‘I have a studio. I’m an engineer at a studio, and I’d like to offer you the opportunity to come in and record for nothing and see if we can put an album together. That’s how Easy to Love got recorded. He wanted us to play down some songs in a session one night, and Easy To Love was played down as a guide track for him to listen to. And that guide track with that live vocal is what came out.

Our final track I wanted to ask you about is Never Give Up (The Reprise version). When does that song date from? The thing I’ve noticed over the last decade is that you’ve managed to go into your archives and release material from a range of periods of your recordings.

From 1990 to 2000. I took another hiatus from the music industry, but on one level of being an artist or a drummer. And a friend of mine in Los Angeles was involved as the CEO for a video production company. And he asked me if I would like to be musical director for the video production company based in LA, which I did for ten years and when I came back to Australia in 2001, after that a gig was over, I decided once again I was going to start writing songs.

And Never Give Up came out of a songwriting session that I did. I started writing on my own at that point. And so it was sort of a personal affirmation to myself to never give up. It was a song that I recorded in Melbourne in 2001 or 2002 from memory, with incredible keyboard player Ollie McGill from a great Australian band called The Cat Empire.

When I was going through the archives and picked it out, I thought that it sounds pretty good. So I decided to wrap a video around it and just put it out on a solo EP around the COVID period. Never Give Up became a bit of a positive mantra for us all at that point in time to not give up on ourselves.

Geoff, it’s been amazing to talk to you and cover so much material way back in the 60s, The Groove, Tin Tin, Bee Gees and what you’ve done after that and your newer solo material. It’s been brilliant. I know people can look you up and you’ve got a Bandcamp and can find out more as well.

Yes, Facebook and YouTube channel and yes, Jason, thanks so much for your interest.

Further information and acknowledgements

For more about Geoff Bridgford: Watch/Listen/Stream/Download/Follow: https://linktr.ee/geoffbridgford

The Groove / Eureka Stockade – ‘The Groove Plus: The Unreleased Eureka Stockade Album’ is released on Frenzy Music.

A podcast version of this interview will be released in July 2023.

Photos used with permission of Geoff Bridgford. Thanks to Grant Gillanders for his assistance.

Also on The Strange Brew, Bee Gee related podcasts with Colin Petersen, Vince Melouney and Blue Weaver