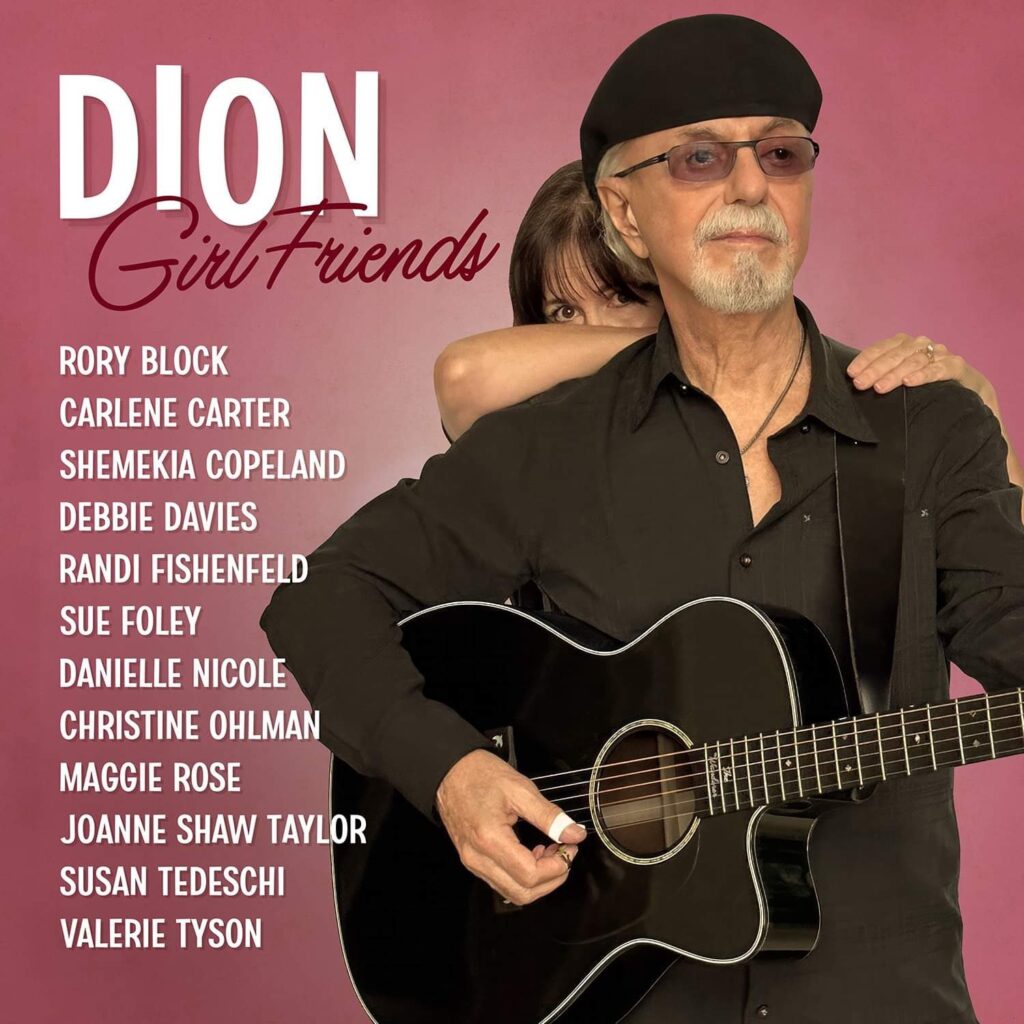

Dion (Photo by David Godlis)

By Jason Barnard

Dion shares insights from his latest album ‘Girl Friends‘, where he collaborates with talented female artists to showcase the ‘female genius’ in music. He takes us behind behind his timeless hits including ‘The Wanderer’ and ‘Abraham, Martin and John’, reflects on lessons learned from Sam Cooke and Buddy Holly and the transformative power of songs. [The podcast version of this interview is also available]

‘Girl Friends’ is part of a run of fantastic records. What was the inspiration for the album?

I had done an album called ‘Blues with Friends’, and I worked with Samantha Fish, and it was so much fun working with her. And, girls, they change the atmosphere of the room, especially beautiful talented women. It was so much fun. I worked with Patti Scialfa, and I love working with her. She’s just delightful. And Bruce [Springsteen] is so helpful. But then I went to ‘Stomping Ground’, and I worked with Marcia Ball and Ricky Lee Jones, and a few other women.

When I started writing on this latest album I thought it would be an interesting thing to write some of the songs as a conversation. Like across the table, like you’re having with a woman. And it just kept going. I got on the Joe Bonamassa Blues Cruise, and I heard Maggie Rose, and Joanne Shaw Taylor. I listen to a lot of music. I’ve always been listening to Susan Tedeschi and Carleen Carter. I love Rory Block. Sue Foley is an old friend. I thought, man, it would be a great idea just to do a whole album.

I didn’t call it ‘Girl Friends’ at the time, but I started to think of writing in this direction. Instead of doing a Tony Bennett album, where you just pick up a whole bunch of traditional songs and everybody sings a verse, no matter what this song is saying, I thought it would be interesting to actually have a relationship kind of song where you’re talking back and forth.

But I didn’t want to make it boring and write them all like that. So I changed it up a little, and I came up with this album, ‘Girl Friends’. Like I said, I listened to a lot of women who are just mesmerising, the distinctive, masterful kind of monster musicians, and a force to be dealt with. They’re unbelievable. That’s how I got that song ‘Soul Force’. I call it the feminine genius.

‘I Aim to Please’ with Danielle Nicole, is the most recent release from it. There seems to be a bit of fun there, especially with the video.

Yes, you know what happened. That song had an evolution in itself. I started it out like a Jimmy Reed thing, and I was singing it down here and it was, it was not risque, it was very sexy. It could go either way. So I started it down there and I was singing the song. Then I had Danielle Nicole come in and she isn’t in my range. She said, “Should I sing it lower or higher?” I said, “Sing it Higher”. It’s good for the contrast. Well, she started singing with such power and energy that every verse on that song is different. I’m going, I start here, I move up here because I’m trying to match her energy. Then I move up here in the last verse. She just kept pushing me. So these are the surprises that happen and I liked it. It wasn’t my original intention for the song.

I felt like it was going in a good place. So I went with it. And man, I’ll tell you, Jason, between you and me and the rest of you guys who will listen to this. Personally, as far as I’m concerned, since Aretha Franklin and Whitney Houston have passed on and gone to a better place, I’ll tell you, this girl is the best singer on the planet. She’s unbelievable.

You mentioned ‘Soul Force’ earlier. Susan Tedeschi is on guitar which adds an extra element to the song.

Yeah, she’s a great guitar player. I love the way she sings. We promised each other that in the future we’ll do a song, singing together. But she’s just so natural. And these girls, they take it seriously. They’re not into fame or being a pop star. They’re into the music. They’re serious and I love that.

Joanne Shaw Taylor is on the song ‘Just Like That’. She’s British.

Yeah, I met her on the Joe Bonamassa Blues Cruise and she said, “I’d love to do a song with you”. And man, can she play. She has a very distinctive voice . She’s a force to be reckoned with, another one. Imagine if these girls were around in the 50s, they’d have to rebuild the Paramount Theater, on an Alan Freed show or something! [laughs] It’s ridiculous. They’re so good.

A song which is more reflective is ‘An American Hero’. What was behind that?

Well, here in America, maybe it’s the same over in the UK, it’s so divisive right now. I don’t know if it’s an illusion of division or it’s the cable channels that just play to their base and like to split everybody up.

But I kind of got sick of it. I said, stop looking to politicians and Hollywood and the tabloids for heroes. Look inside your own heart. This song was written to the ordinary person saying, hey, you be the hero in your environment and the 10 people that are involved in your life. If everybody could do that, this would be a great world. There’s a line in the song that says, “Why are we waiting from afar? Let’s be the heroes that we are.” So I’m asking everybody to be a hero in their own life and take responsibility and not sit around being a victim and think that they’re owed something. Come on, what’s what’s wrong with the word incentive? I don’t hear it anymore. A little earning and merit and using God given talents, which God gave us all. So come on, let’s stand up and do it. Stop complaining. You’ve got all these victims around.

Carleen Carter is on that as well, an incredible lineage.

The Carter family, they’re part of the earth in America. They were born right out of the ground. If anybody would understand that song, she would. And she did. She understood that it wasn’t political. It was patriotic in a way. To be patriotic, you don’t have to be political. Like in England, people moved to England because they loved it. It’s a great, great country. Now you have people moving there that don’t like it. It’s horrible. That to me is unacceptable.

‘Angel In The Alleyways’ with Patti Scialfa and Bruce Springsteen is a special song. What was behind it?

Listen, at my age, I think I’ve been surrounded by my guardian angel because I don’t know how I got here. I couldn’t plan it. The protection and care from above, I’m a believer. I just felt that I was writing it about something transcendent. I’ve been clean and sober for 55 years. I came into a spiritually based 12 step program. I wanted to bring a transcendence to the song and say, hey, I’m doing this and I’m doing that, but I couldn’t plan it if I tried. I’m under the spout where the glory comes out. I’m under this spout of the wellspring of creativity. I’m just being blessed and I’m a grateful man. I wanted to put that in a song. If anybody understands that, it’s Patti Scialfa. She just has a beautiful heart, a good person and looks up. Bruce and her very grateful people.

When I write a song… I listen to so much music, Jason, that I think as I’m listening to it, I know who will sound good on this. It’s not that I write it for them. I just listen to it. I hear somebody that I really enjoy listening to, maybe they’ll give a contribution to the song, the way it is. And in that case, you know what happened? I sent that song to Patti Scialfa. This is the only song I sent out with just me and my guitar. She sent back 48 tracks. That is putting time and love into something. The bass, the harmonies, if you listen to that song, each verse is different. She actually arranged it and produced it, where each verse is very different.

There’s another song of yours from more recent years is ‘Song for Sam Cooke’. You collaborated with Paul Simon. Was that related to when you toured with Sam?

I travelled with Sam Cooke back in the early 60s and he was just a very stand up guy. A kind of statuette, a very intelligent guy, a believer, a very spiritual guy. His father was a preacher. Now that I look back on it, I think that our relationship was based on brotherly love. He taught me that, if race matters to you, you’re a racist. Just as simple as that. It didn’t matter to us. We didn’t look at it. It was like hair colour or eye colour. They’re actually saying something totally different in America now, that it should matter to you. No, I don’t think so. I think I’ll go with Sam.

But he was a very intelligent guy and I’ve seen him in all kinds of situations with people in the South at that time, like calling him names up close. And I never saw him react. I always saw him turn things around in such an intelligent way that he had people look at themselves. I was from the Bronx, I was like, “Hey, Sam, why don’t you whack that guy?” But never. Then it dawned on me one day why he never reacted or got ruffled. He was the most intelligent guy in the room. The one thing he cared about, he wasn’t in the relationship to win. He was in the relationship to bring up what was true. That was his aim. Not to win the argument or to be better or to get over on somebody or to be right. No, he just kind of turned the thing around and would say, “Well, let’s look at what’s true.” He had that ability to show people and they’d walk away tongue tied.

‘Song for Sam Cooke’, is about him protecting me. He took me to a club to see James Brown before James was popular. People were coming on to me. It was kind of like a reverse kind of discrimination. He would say, “Hey, this is my brother. He’s with me. Hands off, relax.” So that’s what the whole song is about. I had it in the drawer for so long, but when I saw a green book, I took it out and I said, “I think I’m gonna do this.” I recorded it with Paul and he got it. It wasn’t about racism or anything like that. The song is about brotherly love.

In more recent years your album from the mid-60s, ‘Kickin’ Child’, finally saw a release.

‘Kickin’ Child’, that’s a song on the album, ‘Blues with Friends’. I did a redo. I didn’t think it was living in the right place, you know? I would sing it at my friend Joe Menza’s house. He’s a great guitar player. I said, let’s do it, we put the song on there. I remember doing it in the mid-60s, but I did a different spin on it, just slightly different that I felt the song deserved. I’m happy the way it came out, very happy.

There’s a song of yours called ‘Your Own Back Yard’. Is that about overcoming some of the difficulties you had in the 60s?

Yeah, I was a drug addict in the mid-60s. I was using heroin with Frankie Lymon. Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers did ‘Why Do Fools Fall In Love’. We were hanging together and using drugs. In February of 1968, he died of an overdose and it shook me up. I made a decision to go to meetings and find out what was going on. I’ve never looked back. I’ve been cleaning sober for 55 years.

But maybe a year after I got clean and sober, I wrote that song, I put that song together. It was just saying, hey, it’s drugs that are a big fool. They’ll kill you. Artists, sometimes they think you take a drug and you get creative. Nah, that’s not so at all. 30 of the greatest songs I’ve ever penned have been the last four years, I’d say. That has nothing to do with drugs or alcohol or anything like that. Man, it has to do with being clear headed and seeing relationships and really tapping into the gifts that God gave me.

Music in general as well as the songs that you write have an impact on others. They help to sweeten life and help to reflect it. It’s transformative. Is that something that you recognise?

Yeah. I love that approach because I’ve been so blessed with people sharing with me how to get to higher ground or to a higher reality, to get out of the funk I was in. They helped me. It comes through in my writing. For instance, I wrote a song called ‘Cryin’ Shame’. It’s about an alcoholic and at the end of the song, he doesn’t get well. Over the 55 years I’ve been clean and sober I’ve seen people that don’t want it. They don’t grab onto it. They just resist. They’re defiant, they’re self-willed. They have very strong wills and they stay in their addiction. And that’s what that song is about. But I wrote it to show you that it isn’t good to stay there. I didn’t let them come out of it. If you know any junkie or alcoholic, the way they do life is to blame everybody. “You shouldn’t. You know what’s wrong with you? You better. You never. It’s your fault. If you’d only!” They blame everybody. They’re big victims. That’s what that song is about.

But most of the other songs, I always say, I’m pretty easy to understand. I heard Jimmy Reed and Hank Williams when I was a kid, and they took me to a place of enchantment or delight, something that I wasn’t experiencing here on this plane. So I always felt like it was so transcendent. I always wanted to put together and develop a song and transmit it to others and get them to feel what I felt when I first heard Hank Williams and Jimmy Reed. That’s been my whole life trying to do that. Whether it’s with the play. We have a play opening up on Broadway here in the fall this year, and it’s two and a half hours long. It’s the same theory. I wanted to take people on a trip and take them to a higher reality and a place of hope. I want them to walk out of the theatre going, wow, you got to see this again. This is great. I want it to be something that cannot be denied.

Sometimes the lyrics express feelings that you cannot express. That seemed to come across even in the songs that you had with the Belmonts like ‘No One Knows’. Lyrics like “My heart is breaking, but no one knows”. It’s a universal language.

You just hit on something that’s truly monumentally of importance to me. Because when I was a kid, there were certain things you couldn’t say. It could kill you, those feelings, you spiral inward and you could explode.

But music, I discovered, you could put a song together like, “No one knows what I go through and the tears I cried for you”. You couldn’t say that to somebody. “My heart is breaking, but no one knows.” But you could do it in a song and not get penalised or feel threatened. Like what’s gonna happen to me if I say this? But in a song, you could say anything and people go, all the guys in the bar room, they keep putting nickels and dimes in the jukebox, I wanna hear that song again.

‘Only the lonely’, you can’t say that to another guy, but you could listen to it all day long and say, that’s a great song. It threatens nobody. It bypasses that place where you get threatened. It just bypasses it and it goes into your soul. It’s almost like a secret I found out. I can’t say these things, but I could sing about them. It’s salvation.

Yes, there seems to be a thread from your new album, ‘Girl Friends’ to your early work, whether it’s ‘Donna The Prima Donna’ or ‘Runaround Sue’. Observing life and that dynamic between men and women that seems to still hold.

Well, relationships are difficult. First you gotta, get along with yourself. Now I gotta get along with you! [laughs] So there’s so much to write about. In the 50s, everybody was writing namby-pamby, ‘Put Your Head on My Shoulder’ or ‘Venus’. I was thinking, you gotta get some girls in here that got some grit, some conflict. So I’ve always liked mixing it up because that’s the way relationships are. So write forever on relationships. You ask 10 people what their definition of love is, and you get 10 different answers.

Something that you’re also known for is reflecting people around you or seeing things that are going on and then putting that into a song like ‘The Wanderer’. You were able to reflect what was going on around you.

Yeah, the fun thing about songs like ‘The Wanderer’, maybe in my early years, it just naturally just came out of me like seeing these wise guys on the corner come out of the ballroom, gangster types.

I heard Muddy Waters do ‘I’m A Man’, ‘Hoochie Coochie Man’ and ‘Mannish Boy’. There’s a thing in the blues that I call bragging rights, you know, “I’m the Hoochie Coochie Man”. So I started out ‘The Wanderer’, I’m the wanderer. Then I wrote, ‘King Of The New York Streets’. Yo, I’m king of the New York streets! Every time I’m putting an album together, it seems like one of these songs emerges. I wrote a song called ‘I’m Your Gangster Of Love’.

I wrote a song called ‘I Got The Cure’ on the new album with Rory Block, I said, “Don’t you want a man like me? Yo, don’t you want a man like me? The kid is here. You want this guy right here!” It’s a bragging rights song. I love those kinds of songs, they have such an attitude, and I picked it up from Muddy Waters, blame him.

There’s another great song of yours ‘Every Day (That I’m with You)’. That was about Buddy Holly, wasn’t it?

Yes, it’s a song written about Buddy. I haven’t done it in a long while. I did it in a video because the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame came down to my house in 2009 on the 50th anniversary of that tragic plane crash. They said, “Would you tell us the story about that tour?”. I did an hour and a half video from A to Z. No one had ever asked me to explain it like that.

I told them what I remembered. My memory is quite good before the crash. After the crash my memory is a little hazy. But I sang that song ‘Every Day (That I’m with You)’ because I really feel like Buddy Holly’s always been an inspiration in my life. He was a very strong character. He was very decisive and a beautiful guy. He told me, “Dion, I don’t know how to succeed, but I know how to fail. Try to please everybody and you’ll fail. Do what you think is right.” So if it wasn’t for Buddy, I don’t know if I would have recorded ‘Runaround Sue’ and ‘The Wanderer’.

When you first heard ‘Abraham, Martin and John’, did you realise that it would resonate with so many people?

No, not at all. Dick Holler sent me a demo and it was totally different. It was a very different kind of song. It was like a shovel. [sings original tempo] So I changed the melody a little and I had a gut string guitar and I started fooling with it.

My mother-in-law and my wife heard it. My mother-in-law said, “Man, that’s the gospel. That’s a good song.” You can kill the dreamer, but you can’t kill the dream. We will pick up on it and carry it further. So I just put the song together and brought it to Laurie Records. In a time when Cream and Jimi Hendrix were very popular, who would think a song with strings, violins and harps would top the charts? I had no idea.

As you say, you’re recording, writing and releasing the best material of your career. Is the plan to just keep going?

I love creating more than I love the road. I just love putting something together that was never there. I want to get it together physically so you could hear it, so you could see it, so you could feel it. I just love that part of this business. I’ve become more of a songwriter as I’ve aged. One beautiful thing about still being here is I learned how to ask for help. I never could do that when I was young. I had to do everything myself. Now I ask Mark Knopfler or Eric Clapton, who by the way is so generous. These guys are so generous, it’s unbelievable. Eric Clapton just wrote a forward to a new book I wrote. He’s a good man, he’s a giver. He knows when to give and when not to give.

But I’ve learned to ask for help and it’s wonderful to feel that kind of response and I’m so grateful for it. It hurled me into a place. I feel like I caught a wave and I’m just riding the wave. It’s like it’s effortless. So it’s a beautiful time of life. I used to be frightened to ask for help. God forbid you should ask for help, you’re weak, you know? You know, be self -sufficient, be strong, do it yourself! Nah, I get that, don’t get me wrong. I get that. But this isn’t like taking, it’s just being open to receive gracefully.

That’s a great way to close. Thank you so much for your time, Dion. I’ve loved listening to ‘Girl Friends’, your recent run of albums and your amazing body of work.

Thank you, Jason. Pleasure, man. Thank you. Appreciate it so much.

Further information

Dion’s new album ‘Girl Friends’ is released by Joe Bonamassa’s KTBA Records on March 8, and is available to pre-order from ktbarecords.com

The podcast version of this interview is also available on The Strange Brew.