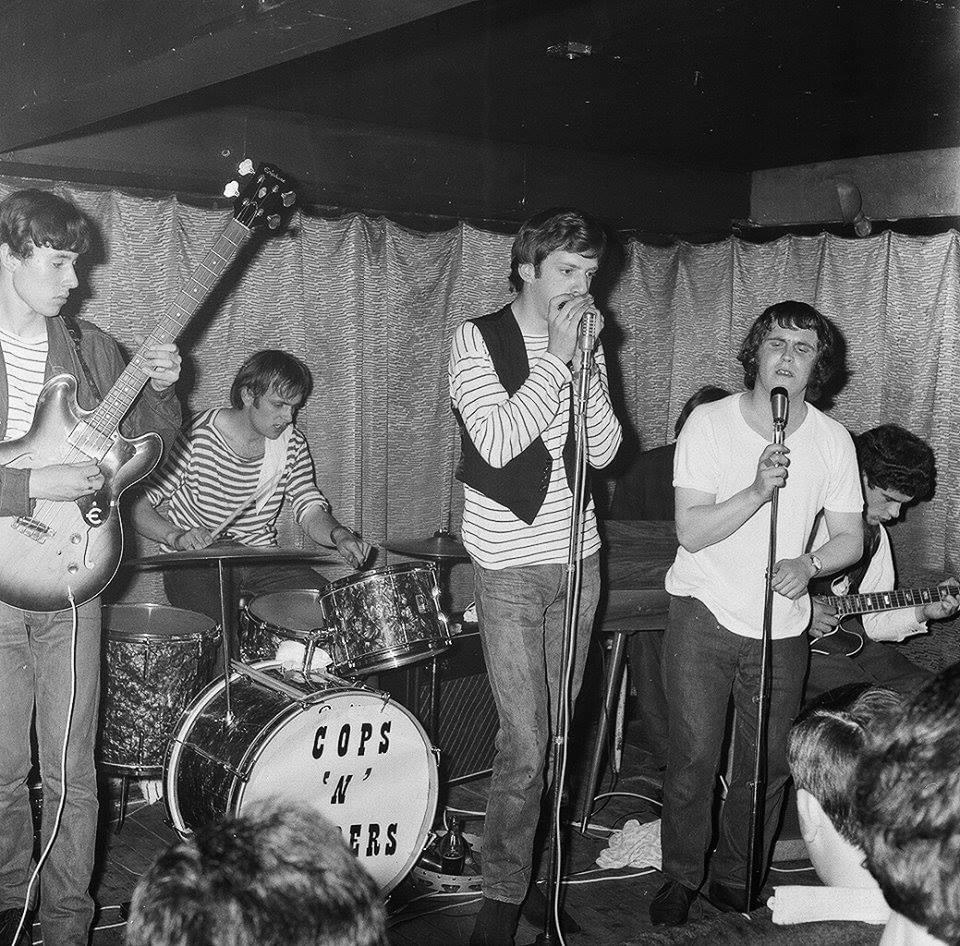

Cops n Robbers original six piece, left to right: Steve Smith, Henri Harrison, Keith Canadine, Terry Fox (hidden behind singer Smudger), Smudger Smith, Brian Raines. Photo: Studio Club 1964, by kind permission of John Ricks

Organ player Terry Fox was an integral member of ‘60s beat/R&B legends Cops n Robbers and co-wrote all of their original material, notably ‘You’ll Never Do It Baby’, which The Pretty Things covered on their second LP. He’s putting the finishing touches to his book about the band and speaks to Nick Warburton.

I understand that Cops n Robbers was formed in Watford, Hertfordshire in 1964 and you took your name from a Bo Diddley song?

Terry: Cops n Robbers was the 1964 New Year resolution of Henri Harrison; a trad jazz drummer and friend. He wanted to form a Rolling Stones type group, not only to emulate their kind of music but, hopefully, their fame and fortune too.

Henri tried to interest me in his group when it was called The Blues. But though it was exciting, it was bluesically a mess. Mick Softley and Donovan Leitch were in it and six or seven other people. Folkies. They played blues but were too lightweight for Chicago style British R&B.

Can you tell us about the band’s formation and how you knew each other?

Terry: Yes. The name Cops n Robbers was taken from a Bo Diddley song at the suggestion of Brian Jenkins the piano player I replaced. (Ed: Brian went on to form another Watford R&B group, Paul’s Disciples, which recorded a Blind Lemon Jefferson song on Decca.) The name was meant to be written as: Cops n Robbers, with a little n, but when Henri bought the stickers to stick the name on his kick drum, the shop only had big Ns left, so that’s why everyone puts Cops ‘N Robbers. Ha.

When Henri had sorted out a better line-up and had got an offer of a management contract, I was persuaded to leave my jazz quartet, the Giles-Fox Hot Four, to play blues piano for him.

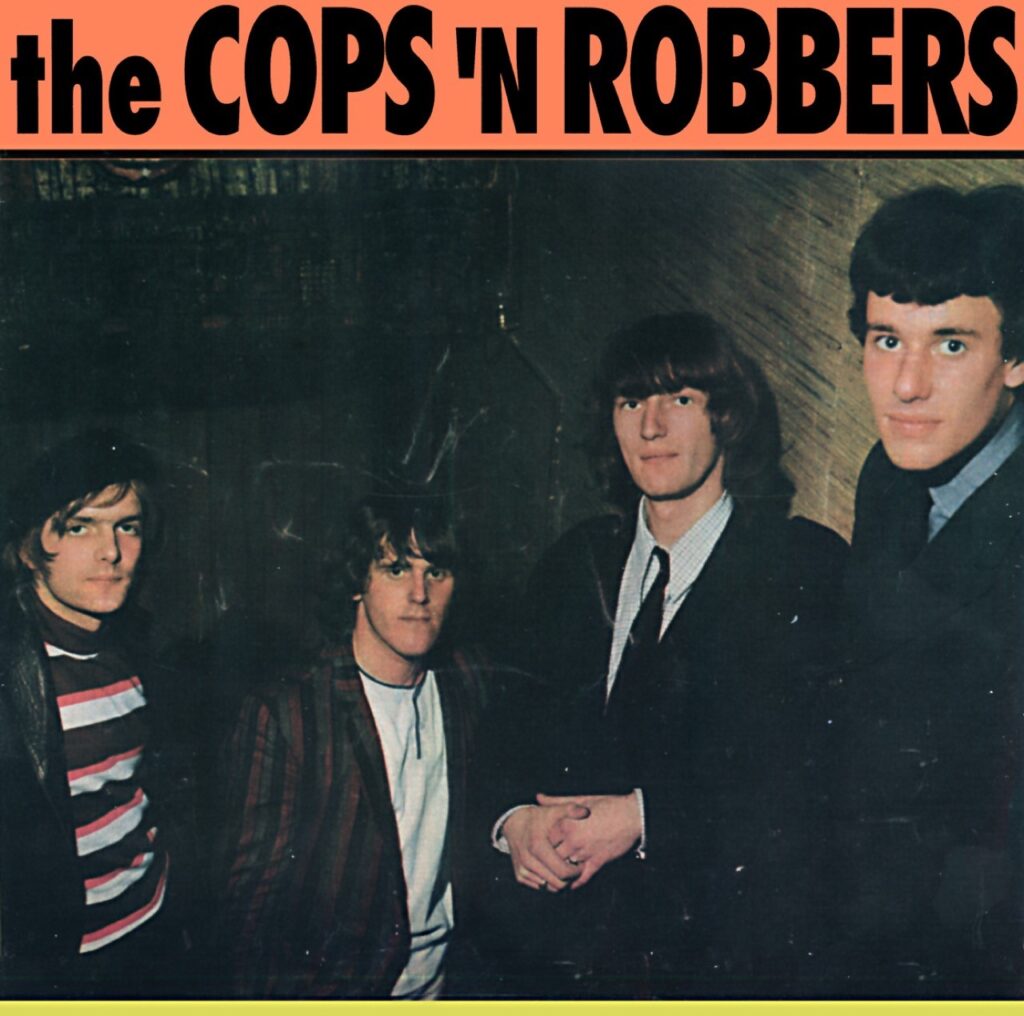

Cops n Robbers was a six-piece when I joined in June 1964: Brian ‘Smudger’ Smith (vocals), Keith Canadine (mouth harp/backing vocals), Brian Raines (lead guitar), Steve Smith (bass guitar/backing vocals), Henri Harrison (drums) and yours truly (piano). It became a four piece for economic reasons in July 1965.

You were quite unusual in that you didn’t have a lead guitarist in the band for quite a while. Was that a conscious decision as your band’s line-up and size changed throughout its existence?

Terry: Our lead guitarist, Brian Raines, left shortly after we signed our management contract in September 1964. He’d landed the office job he’d hankered after, and jacked in playing music for a living to take it up.

We were suddenly without a guitarist and had gigs to do. Smudger volunteered to play rhythm guitar as a stop gap. Life being what happens while you’re making other plans; he stayed on rhythm guitar until he left in October 1965. We became a five-piece again when Dougie Ord joined from The Fairies in 1966.

What are your early memories of Cops n Robbers’ first gigs in 1964 as a six piece and the reception you received?

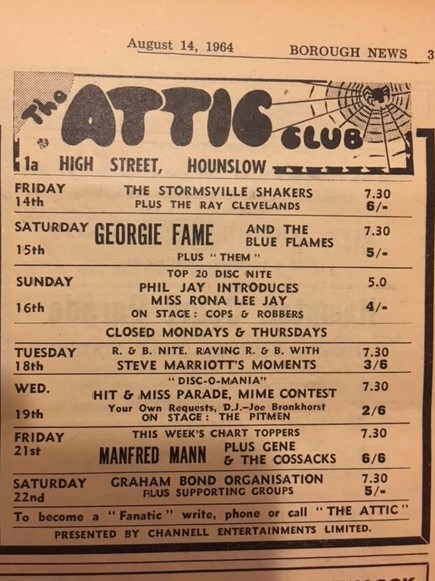

Terry: The huge numbers of girls in the crowd compared with trad jazz gigs, and not being able to hear myself play. The group was mega loud for its time and totally anarchic. Britain was Chicago blues crazy. The Watford mods, beats, and ravers – ‘sharp guys and chicks’ in the parlance of the time – made as much noise as the group. Watford gigs were bedlam. When I played my first gig at Cops n Robbers’ manager Rodney Saxon’s club, the Studio Club, Westcliff on Sea in Essex, the local paper described Cops as “the Group That Has Hit Southend Like a Bomb”.

It was exciting, but I do recall feeling jarred off because we were playing fewer blues numbers than Henri had promised me; more Chuck Berry than Muddy Waters. But the success of it was a thrill. Smudger Smith was a rocker really, an amazing singer, and second only to James Brown and PJ Proby at working an audience. [He was] second only to them because we played on smaller stages.

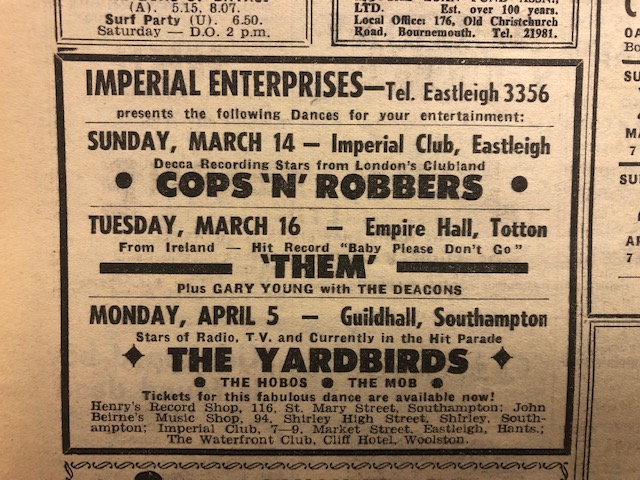

You signed with Decca Records in 1964 and cut your debut single, which comprised two non-originals, a cover of ‘St James’ Infirmary’ backed by ‘There’s Gotta Be a Reason’. How did the deal come about and what do you recall about recording the tracks? The single, released in November that year, turned out to be a one-off for the label as you moved on to Pye afterwards.

Terry: Our first Cops n Robbers recording session was a six-track demonstration record cut at Jackson’s Studios in Maple Cross. It was paid for by our manager Rodney Saxon and co-produced by the Jackson brothers and our co-manager Peter Eden. That got us a five-year contract with Decca. Pete Eden’s friend, a song-writer and producer called Geoff Stephens, who was a friend of Mike Leander (aka Micky Farr), an up-and-coming young producer at Decca, negotiated our contract.

Groups were told what to record in those days. Mike Leander got it in his head that the time was right for ‘St James Infirmary’ to make the charts. The song’s similarity to The Animals ‘House of the Rising Sun’ won’t pass unnoticed. Smudger and I had written a couple of songs then and were expecting to have the B-side. We were told our songs were “too good for B-sides” and, surprise, surprise, we did ‘There’s Gotta Be a Reason’ – a Stephens/Farr composition! It is useful to remember the B-sides of singles generated the same money as A-sides. Donovan was there, sitting in a corner watching. We cut both sides in three hours. Our time was up at midnight. As we left Lulu and The Luvvers were coming in for their session.

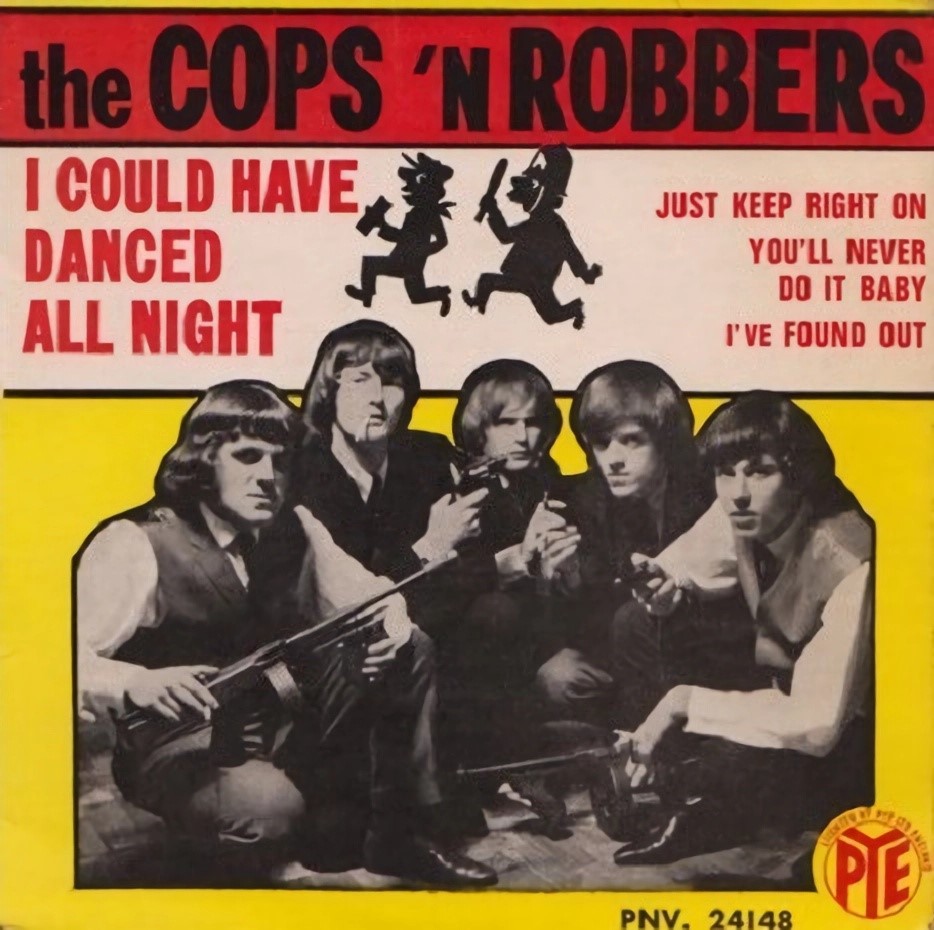

There was a bit of gap before your debut single for Pye – a cover of ‘I Could Have Danced All Night’ backed by ‘Just Keep Right On’, which I understand was one of the first fruits of your song-writing partnership with Brian ‘Smudger’ Smith – came out in June 1965. What’s the story behind this session?

Terry: Ha. Mike Leander was convinced ‘St James’ would be a hit. It wasn’t, but it did enough for Decca to want to get another single out. We recorded some tracks, but were moved across to Pye without them being released.

‘I Could Have Danced All Night’. Whoah! It’s a shocker, isn’t it?! I played alto sax on that. I’d only had it a few weeks. Smudger played the trumpet as well as singing. It was Pete Eden’s idea to record this song. Pete was always one for novelty, the surprise element. He knew Smudger liked Ben E King who had recorded this song on an album. I was so scornful of it I didn’t bother to listen to the King version. Stupid of me as it turned out because there’s some great boogie piano on it that would have perhaps redeemed it for me. We did Ready Steady Go! with that song, halfway through touring with the world’s greatest blues man. What a contrast.

We went to Pye because Geoff Stephens and Peter Eden had got a contract with them to produce Donovan and they pulled us across because Pete wanted to produce us as well. I would have stayed with Decca. Mike Leander had got a lot of edge as a producer, and I liked that. He was the only bloke other than George Martin to arrange a song for the Beatles – ‘She’s Leaving Home’.

Having said that, I love Pete. We got back in touch after 50 years. He’s a great rarity in the music business, a man of faith, as honest as the day is long. He masterminded Donovan’s success, introduced Don to jazz and produced some wonderful records for Don, and became a great jazz and folk producer.

But when he was recording Cops n Robbers, Pete was new to the game of recording groups, learning the business, and there wasn’t a budget for retakes, etc. We were all making it up as we went along in those days. [We were] setting the precedents that other groups were to follow.

Regarding song writing: Pete Eden sent me and Smudger to meet Ashley Kozak for some show biz advice. Kozak was good musician (a bass player) and was working, or had worked, for NEMS, Brian Epstein’s outfit. Kozak said, “You gotta write your own songs. That’s where the big bucks are”.

It had not occurred to us before. Not on our horizon. My thing was blues, what you did with and within the song, and there were enough blues songs to last me a lifetime already written. But we went straight back from meeting Kozak to the piano at my parents’ gaff to give it a go. We wrote two songs in about twenty minutes: ‘You’ll Never Do It Baby’ and ‘I’ve Found Out’. Henri loved them and they immediately became part of our play list.

Me and Smudger thought little of it. It didn’t inspire us to write loads of songs which we could have done. I can’t explain it really. I think I found it beside the point and a bit embarrassing.

Biographers sometimes cite the similarity in your ‘wild’ R&B approach to that of The Pretty Things who cut the Smith-Fox collaboration, ‘You’ll Never Do It Baby’. How did they come to cut the track and why didn’t you release your own version in the UK when it appeared on a French only EP in August 1965?

Terry: We were wilder than the Things onstage when Smudge was with us – apart from Viv Prince, that is. Our songs were signed to Geoff Stephens’ publishing company, and he would plug them to other groups. The Pretty Things were going to do ‘You’ll Never’ as a single. I don’t know what happened there, but it came out the following year on an album. It’s become a bit of a garage classic since then, played by groups across the world.

As to why we didn’t do it, there was never a grand plan for Cops n Robbers. We were on the road forever gigging and didn’t really notice how random it all was.

The French release is interesting and suggests that there was a bit of a fan base there. Did you ever get to play in France or anywhere else on the continent?

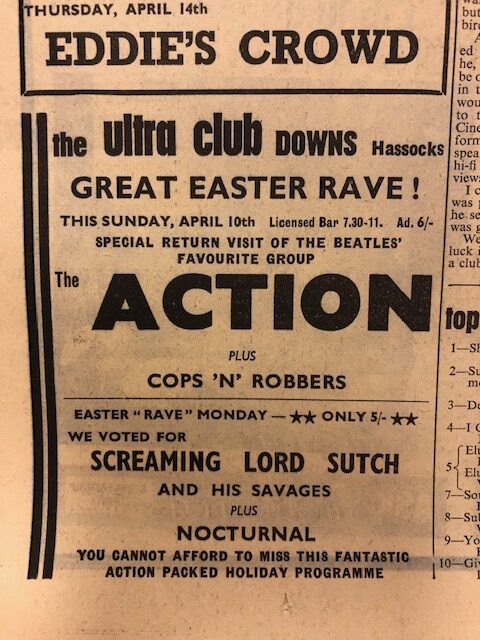

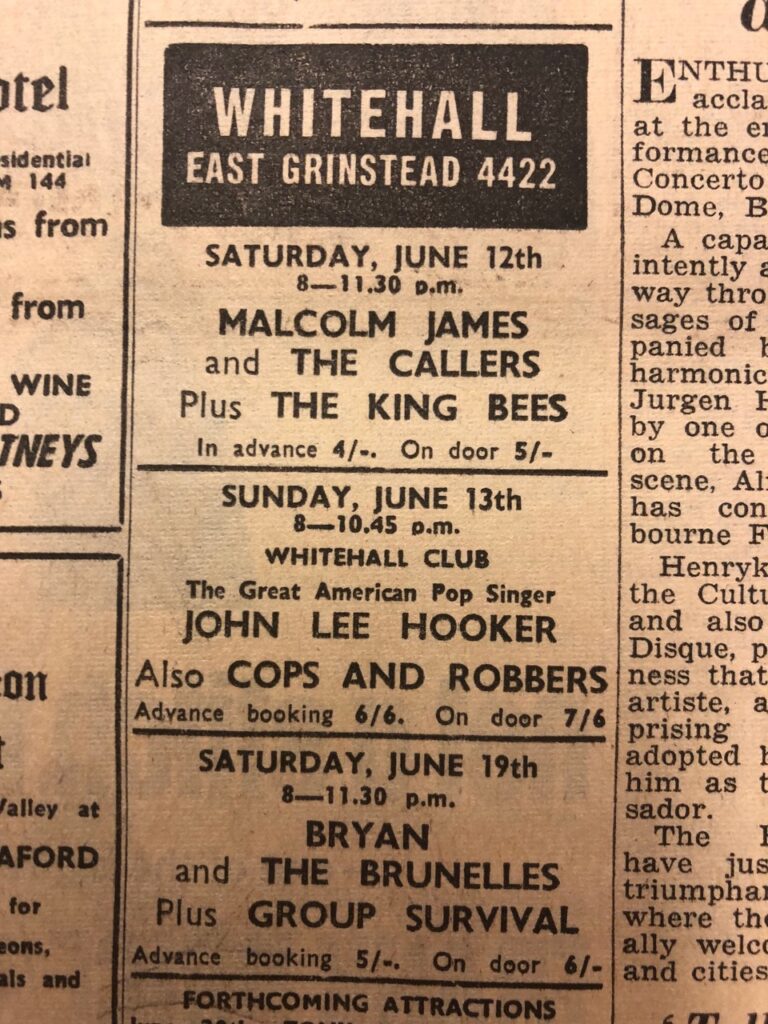

Terry: Cops n Robbers management not capitalising on any of our successes was a mystery that took my writing of When Henri Had the Blues to solve. It wasn’t just them not following up on our success in France either. When we played the Paris Olympia, I hit into the organ intro of ‘St James Infirmary’ and a huge cheer of recognition went up from the French audience. It hadn’t been released in France, but they knew it. Mick Jagger and Brian Jones dug Cops n Robbers. This was never followed up. We were one of the first Brit groups to back Buddy Guy. Nothing. Our huge artistic success backing John Lee Hooker for his ’65 tour has been written out of history. And so on, and so forth.

The answer turned out to be not just that we had inexperienced management, although that was an element, but because we had not been signed up to be made famous. Our advantage to our management was to play in a small orbit around our manager’s club to be available to fill any gaps in his club bookings. They wanted us to be well-known, but not famous enough to be taken away from them. It’s funny really. [It was] something that was hidden in plain sight.

You played a couple of gigs opening for The Who and became good friends with them. What do you recall about these gigs?

Terry: The Who were a fab group to work with. Fantastic. Wonderful musicians. Wonderful songs, and lovely, friendly, grounded geezers. The first gig we opened for them, at Bishops Stortford in 1965, the stage was too small for two bands’ worth of gear. Keith Moon lent Henri his kit. Moonie loved our lead singer Smudger Smith. “I love you, man,” he told him. “You loon about like I do.”

The second gig we opened for The Who was at Basildon in 1966. Me and Henri went for a Chinese with Pete and Roger afterwards. I am so pleased that The Who got as big as they did. No group has deserved it more.

Can you tell us a bit more about how you developed your song-writing partnership with Smudger?

Terry: As I suggested earlier, we didn’t take it seriously, so it didn’t really develop. We wrote a few together and a few separately. Our ‘Oh My Love’ was recorded by The Artwoods – Ronnie Wood’s big brother Art singing, and John Lord (he still had his aitch then) on keyboards. The track showed up fifty years later on the soundtrack of a French film Marguerite et Julien. You can YouTube the trailer for the film. They’ve used it really well.

When Smudger left Cops, I stopped bothering. I could kick myself now. I could have made my family better off. Not that I had one then. I’ve written dozens of songs since. Good songs. I’ve played them live but never recorded them. At the time I just saw myself as a bluesician. That’s all I wanted to be. That’s enough, isn’t it?

In August 1965 Pye shipped your third and final UK single, a cover of Bob Dylan’s ‘It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue’, backed by yet another superb Smith-Fox number, ‘I Found Out’. Can you tell us about this session and why the Dylan number was chosen over your original material?

Terry: Pete Eden’s idea and production. I love Smudger’s singing of that great Dylan song. Not even Van Morrison made as good a job of it. I wasn’t happy about my one-take organ solo. I just laid it down to check the sound out, but Pete said, “No. no. Leave it. It’s great.”

You did record some more material that wasn’t released at the time, but was later picked up by Distortions Records in the US and included in a comprehensive compilation in 1997. Did this pull together everything you recorded or are there any other gems still out there? What about TV work?

Terry: The previously unreleased Distortions stuff was those Jackson demos I told you about. Decca has, if I recall it correctly, three or four unreleased songs. I have a home recorded demo of Cops n Robbers when Dougie Ord joined. It’s on a 7-inch acetate and I think too knackered to be played now.

You’ve shown me your gig listing and like others from that period you were constantly on the road. Do any particular gigs stand out?

Terry: The gigs we did with The Who are fondly remembered. The gigs we played with the Graham Bond Organisation are stand outs. Every single minute of every gig, rehearsal, jam and conversation we had with John Lee Hooker are precious memories. A gig we played at The Place in Stoke on Trent where I met Lynda who I later married is naturally a significant memory.

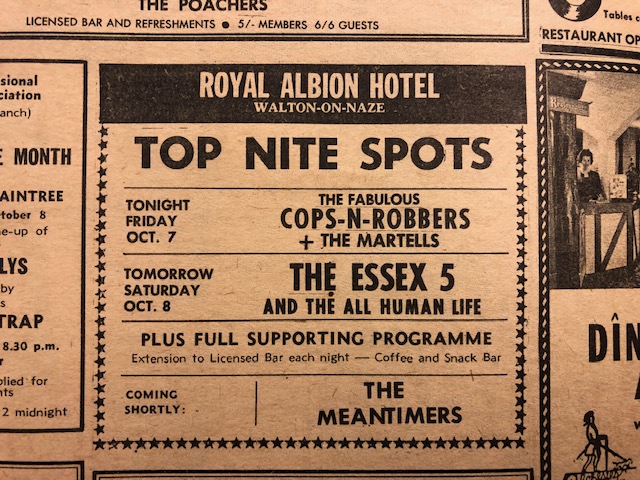

Although you were from Watford, the band played a lot in the Southend area during 1965-1966. What’s the story there?

Terry: Our manager Rodney Saxon owned the Studio Coffee bar and live music venue in Station Road, Westcliff on Sea.

Is it true that the late Wilko Johnson, guitarist with Dr Feelgood, saw singer Smudger Smith while you were playing in the Southend area and was inspired by his ‘leer’ and later based his stage persona on him?

Terry: Absolutely true. I heard a radio interview a couple of years ago between Bob Harris and Wilko when he told him he used to see Cops n Robbers at the Studio Club. He said when Smudger took a solo, “He looked so angry.” Smudger was not a lead guitarist, but he would play the occasional solo, strutting around the stage, scowling with his dark, staring eyes. If you’d seen them both, you’d see the connection immediately.

Not many people know that Donovan played some gigs with you and I understand that without this profile, it is unlikely he would have been known outside the British folk circuit.

Terry: Yes. True. The British Bob Dylan. We put him forward for it. Ha. It’s all in my book. It’s not quite how Don tells it!

The B-side of your debut single on Decca had been co-written by Geoff Stephens who also co-produced some of your singles. He would subsequently form The New Vaudeville Band, a group that Henry Harrison would join in late 1966. What prompted him to move from such a highly revered R&B band to what many have considered a novelty act?

Terry: Good question. I have a chapter on the Vauds in When Henri Had the Blues. Geoff Stephens approached me to set up the band for him. I was to be the singer, would you believe? I thought it was such a pile of shite, I couldn’t do it. I messed Geoff around badly. Henri had left Cops n Robbers by this time and was looking for work. I passed it on to him. He linked up with our mate Bob Kerr of subsequent Whoopee Band fame, who was with The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band at the time. Me, Henri, and Pops (Bob Kerr) used to play a lot of trad jazz together around St Albans ‘63/’64. Might have even been ’62.

Alan Whitehead from The Loose Ends stepped in briefly. He then spent an equally short time with The Attack before occupying the drum stool with Marmalade. Tell me about the comings and goings at the end and why Cops n Robbers were essentially ‘put to bed’ in December 1966?

Terry: Henri left and we got Alan in. The line-up of Cops n Robbers’ final six months incarnation was: Dougie Ord (aka Dane Stephens) (lead vocals), Colin Strange (lead guitar/backing vocals), me (Hammond organ/alto sax), Steve Smith (bass guitar), Alan Whitehead (drums).

Alan was a fantastic drummer. He is a hugely nice bloke, a great laugh to be around. I can’t speak highly enough of his drumming. He doesn’t just lay down a beat, he plays the song. He brings new life to everything he plays.

It was me dropping out of Cops n Robbers with exhaustion and chronic anxiety syndrome brought about by lack of sleep, greasy spoon café food, boredom (remember the Charlie Watts quote about five years rock and roll and twenty years hanging about?), exacerbated, no doubt, by smoking draw and popping pills. The group played two or three gigs without me then packed it in.

What did you end up doing after the band’s demise? It seems incredible that a musician – and a song-writer – of your talents would abandon a career in music.

Terry: Thank you, though I suspect you over praise me. First, I did nothing but sleep. Then I did some factory work before moving up to Stoke-on-Trent to be with Lynda. I played some blues for a while with a wonderful singer/guitarist called Dick Wardell. When he left for a life in Scotland, there was no one up here of his standard to play blues with and my piano playing fell into disuse.

In recent years, you’ve been working on a book that covers the band’s career. Can you tell us more about what prompted you to write about Cops n Robbers? I understand that one of the reasons was that the band backed John Lee Hooker on a UK tour, but it has erroneously been credited to John Lee’s Groundhogs who recorded an album with him in 1964 that was released in 1965..

Terry: Yeah, pretty much. I was idly googling Cops n Robbers one day and realised the group had largely been written out of history. John Mayall backed John Lee Hooker in 1964. When the tour was extended The Groundhogs took over. Cops n Robbers were chosen to back Hooker in mid-1965.

I was pissed off to discover that in a sloppy piece of journalism, Charles Shaar Murray in his book about Hooker, Boogie Man, he refers to us as “Newport’s own brand of codswallop”. Murray had passed on that libellous inaccuracy from a clown called Tony Lennane who claimed to have been at the gig and had this special relationship with John. No photos, mind, and Lennane’s a photographer.

But more than that negative stuff, I came across a post by ‘anonymous’ on the Psychedelic Rock ‘n’ Roll website: “Pete Townshend in a talk he was giving at a theatre in Ealing in 2014 was raving about this band . . . He wanted to know what happened to them.”

I began writing in earnest in January last year. I have previously toyed with the idea and even attempted bits of writing, but nothing came of it until now.

What’s the latest with the book? Are you looking for a publisher?

Terry: Yes, the right publisher would be great. One with good distribution. I’m more or less done writing it. You can carry on writing a book forever, can’t you? There is always more to say. It’s just structural things now and final edits.

Terry, thanks so much for sharing your memories about the band and good luck with the book.

Terry: My pleasure. Thank you, Nick. Thank you also for all you have contributed to the Cops n Robbers’ gig list. I hope people realise what a talented music journalist and historian you are.