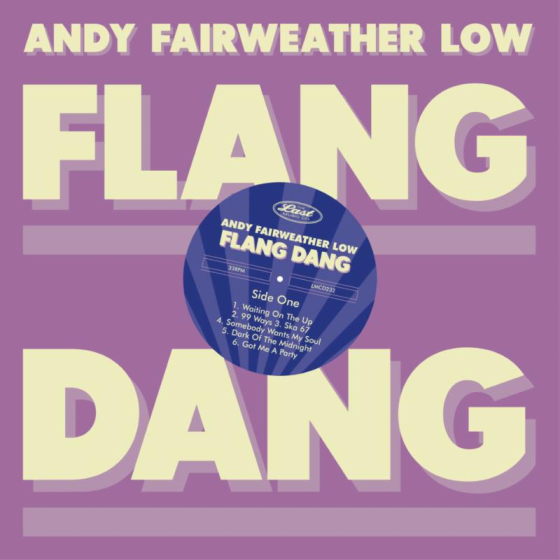

Andy Fairweather Low speaks to Jason Barnard about his new album Flang Dang, his first solo album in 17 years. He also covers his highlights from his time as lead singer of Amen Corner, solo hits and time playing with Roger Waters, George Harrison and Eric Clapton.

I’ve just been listening to Flang Dang over the past weekend. It’s a cracking album and I understand that you basically did everything except the drums?

Yes. I make demos at home. I’ve got a Boss [BR-]1180 eight-track machine and for years I make my demos at home. The recording quality is bad but I love them but the one thing I hate about them all is the drum machine because every track I do starts off like this [imitates sibilant hi-hats] and then we’re in. But it helps me record the track. I got offered a free week in Rockfield by Kingsley [Ward, co-founder of the famous recording studios based in Monmouthshire] in the lockdown. He said, “Just come down. I’ll give you the week for nothing. Be good to see you.” Because I went into Rockfield in 1965, right at the beginning when it was a potato plot, so I’ve got a bit of history there. I asked Paul [Beavis, drummer with the Low Riders] if he’d come and just replicate all those drum patterns so I didn’t have to tolerate that machine anymore. And [I played] everything else. I played bass with Roger Waters for 24 years. I love playing bass and a few other things for Roger as well but generally, in the beginning, my role was to play bass. Yes − the guitars and the harmonies. No keyboards − just guitars. I loved it. Eventually I had three weeks in Rockfield – the one for nothing and I paid for the other two weeks, even though Kingsley did offer me the other weeks for nothing and I went, “No. No. I’ve got to pay.” I took money out of my pension−

[Andy is interrupted in mid-flow by another call]

That actually was John David who was the bass player on La Booga Rooga [Andy’s second solo album, released in 1975] and [on] my stuff and in the band in the 70s when I worked on A&M. There you go. Funny old world.

And the lyrical theme as well. There’s just some great references there. ‘Waiting On The Up’ [the opening track on Flang Dang] is a great example. You’ve got that theme of grabbing the bull by the horns.

Oh yeah. Thank you, because I’m really pleased. Lyrically. I don’t know where− I mean, I spent a lot of time writing them and then, when I look back and I’m like Yes, kind of like that. So, yes, I’m really proud of the lyrics but it does take me a long time. It isn’t something that just− I have to put the time in. I have to waste tons of paper before I go, “That’s it. I like that.”

When was your last album of original material then?

Well, the last solo album, literally that was me, and not me and the Low Riders, was [around] 2007. I finished the Dark Side of the Moon tour with Roger and I released the album and I got a phone call from Roger saying, “We’re going to do The Wall. I’d like you to be on it.” And I said, “But there’s not much for me to do.” There wasn’t much for me to do on Dark Side of the Moon. For half the set I was sitting out at the back in big stadiums watching other people play and there was going to be even less for me to do and I went, “Rog. It’s not enough for me to do.” I’m not the guitar player in that setup. I’m sort of a utility player − a bit of this and a bit of that and I went, “I know my album’s coming out. If I’m going to want to be known as a guitar player I better get out there and do it.” And he said, “Well, we’ll find something for you to do.” And it was a fabulous offer but I just couldn’t do it. We’re still very, very good friends with Roger. Spoke to him the other day. That relationship is really strong − as my friendship with Eric [Clapton] and 99.5 of the people that I ever worked with.

‘Stand Up’, again, has got one of those overarching themes of the album.

Oh yes. I figure I’m just writing the same song over and over again and I just get a few details every now and again. It’s funny, I just got sent a clip of me on the Old Grey Whistle Test in 197− maybe 6 or something [October 22 1974] playing ‘Spider Jiving’ live with hair and an acoustic guitar and a real good band and, you know what? I loved it. It was all right. I’m proud. I can look back and go, “Yes. That was good.” And ‘Spider Jiving’ − I love the lyric of ‘Spider Jiving’ − I play that now. I’m going to hopefully keep on writing lyrics that make me go, “Yes. I like that.” It’s about what I like, in truth. It’s all about what I like.

‘The End of All the Roads’ as well. That’s a special song.

Funny enough, I can tell you this now, it’s the song I wish I’d never written but, seeing I’m in a situation now, I just wish I’d never written that song but, I also think, for me, it could be the best song I’ve ever written. That’s my judgment, looking subjectively. It was the last song we recorded on the album. It was about two o’clock in the morning − myself and Paul. The drum kit was set up. I got the acoustic guitar and I sat in front of the drums and I played it and I sang it. I then put the bass on and then put the harmonies on afterwards. What I would have loved is a big orchestra playing – big string section. But the truth is the album was meant to be just me playing. Obviously Paul was there. And to put strings on would have just taken away from the fact that I produced it. A lot of the noises that come out were the noises that I got from my demos. One thing − the engineer, Joe F Jones, was just phenomenal. I have a little Supro amp and I have an Ascot amp with an eight inch elliptical speaker and I’ve got my own amps and I love a dirty old sound and Joe said, “Well. I’ve got this tape recorder. Why don’t you plug into this Ferrograph?” And I did. Oh! What a sound. It’s on ‘Waiting On The Up’. And it’s on a lot of the tracks but that guitar sound comes from Joe’s tape recorder. Fabulous.

The album’s got a real classic sound that doesn’t date. You’ve got elements of blues and country but it’s one of those albums that you could listen to in 20 years time and it will just be timeless. Is that something that you aim for?

No, no. I don’t aim for it. That’s what I do. It’s like with me and my guitar. I plug in with a lead, straight. I never got through to that rack-mounted system that everyone got into and, for some reason, I never changed and now it’s coming back round to that. I have a verse and a chorus, a verse and chorus, a middle eight and a verse and a chorus and I never took a detour from that. That’s how I liked listening to songs and that’s how I’m writing songs and, unfortunately, it’s way out of kilter with what’s going on now but it’s like I said − I took my money out of the pension and I did it because I wanted to do it and, yes, I know it’s not really whatever’s being played on the radio now. In fact Zone-O-Tone, my last album with The Lowriders, was taken to the BBC and the guy − the head of BBC then for Radio 2 − said, “Don’t bother bringing me that. I’m not going to play this album.” Because, yeah, I’ve had my 15 minutes [of fame] maybe two or three times. So it’s the way of the world but it’s not stopping me from actually getting out and playing it. We finished now just about a month ago on the road and I played about four songs from the new album on that and they really work live. That was a real bonus for me.

For me, it’s just a sound that will constantly keep coming around even if it’s not the flavour of the month or the minute. There’s a bit of a thread; reading about your early inspirations of one of them was when you saw the Rolling Stones in 1964.

28th of February 1964 [Sophia Gardens Pavilion, Cardiff − part of the All Stars ’64 Tour organised by Robert Stigwood]. I know because Bill Wyman, the Rolling Stones coffee book that he wrote [Rolling With The Stones] − fabulous book, because I like pictures. I don’t like to read too much. And it had the setlist from that gig in Cardiff and they started− They weren’t top of the bill. Mike Sarne and Billie Davis I think were top of the bill. [They ended the first half. John Leyton was the headline act.] Jet Harris was on the bill. Bern Elliott and the Fenmen, The Leroys were on that bill and the Stones. I think they started the second half and the first song they played was ‘Talkin’ ’Bout You’ and which was confirmed by Bill’s setlist which was in his book [cf p101]. It got me like a virus and it still got me, thankfully.

And that ultimately led you to learning the guitar and then into Amen Corner?

Yeah. I played guitar before I formed Amen Corner and, when I formed Amen Corner, I split up two bands in Cardiff, one called The Dekkas − I took Neil [Jones] the guitar player and Clive [Taylor], bass from that band. Neil’s not with us anymore but he was my brother-in-law. And then Brother John and the Witnesses. I took Dennis [Bryon] and Blue [Derek Weaver] from that band. Dennis was the drummer. Blue was the keyboard player. Both ended up playing with the Bee Gees and, when I was at my lowest moment, both became tax exiles in America through ‘Saturday Night Fever’ and ‘Jive Talking’ and all of that. And I’d formed the band and then realised, well, there’s a guitar and a bass player and we’re playing soul music, basically. So it was Steve Cropper and “Duck” Dunn [members of Booker T. and the M.G.s] and there was no place for me who wanted to be Steve Cropper and a bit of Eric Clapton too. So I decided just to sing. I thought, that’s easy, because I didn’t have to worry about breaking a string or tuning the guitar. So I did that for a while and then it just wore me down being that I’m not a great singer. I’m just a guy who sings and we were only playing for about 20 minutes, a lot of the time, maybe 25. And a lot of people weren’t listening, which was part of the thing about being a successful pop group. You just get on there and people start screaming and you go Wow! this is really good and then, night after night, travelling all those miles and you’re going but nobody’s listening. Yeah, it’s a funny old deal, the pop music world.

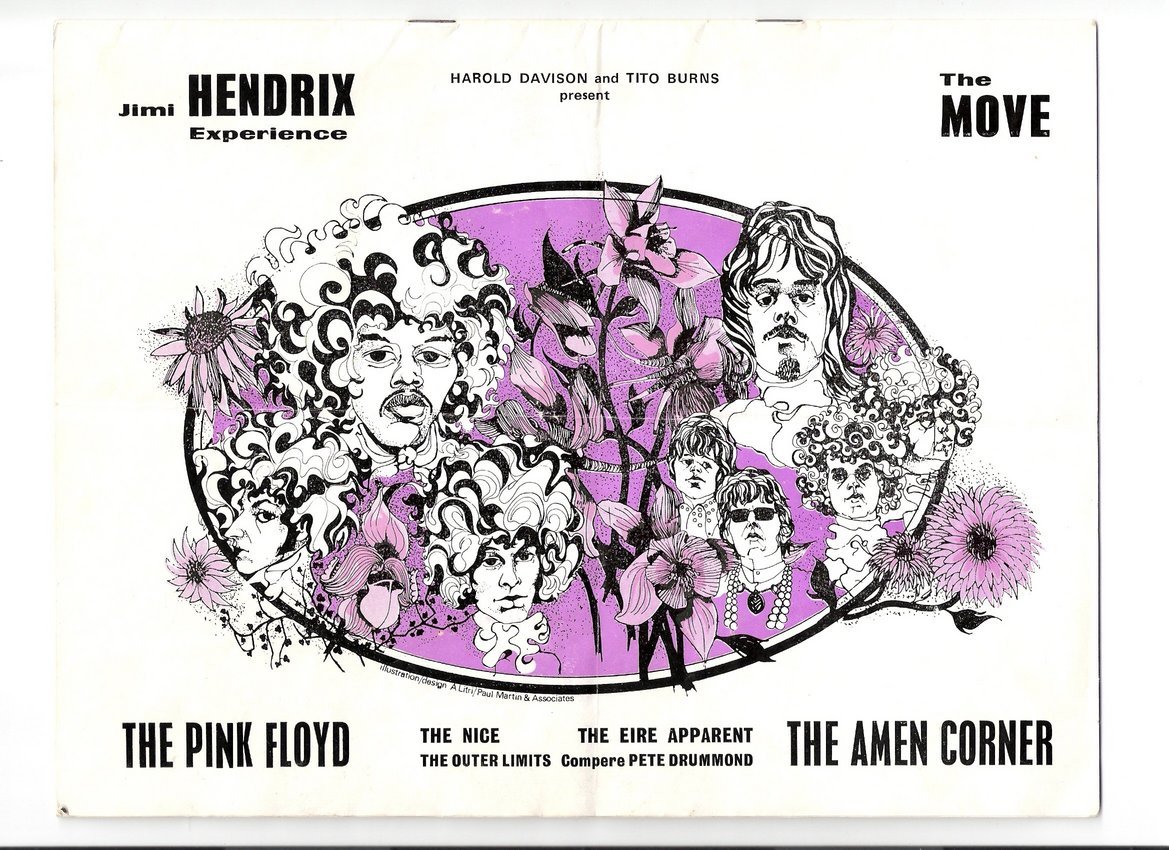

It is. I’ve previously spoken to Jeff Christie, who was in a group called The Outer Limits who were on that amazing 1967 [Jimi] Hendrix/[Pink] Floyd/Move tour that you were on as well. That must have been quite remarkable. All that talent in one place.

It was. It was really special. I mean, I can still see me up in the air looking down at the sound check at the Albert Hall when Hendrix was running through his sound check there and he got on the drums. I remember him sitting on the drums and I remember what he played. ‘Spanish Castle Magic’ was the song but he was just dabbling around on the drums. Yeah, we watched that. That was twice a night − not at the Albert Hall, it was just once − but all the other venues. And The Outer Limits, I remember them. Pete Drummond was the compère. Outer Limits would come on and play one song. And we had a few – about 15 minutes, I think. The Move had 15 minutes. Hendrix had 30 minutes. The Pink Floyd− It’s funny because, 1967 that was, and it was about ’84 that I get a phone call from Roger Waters. Never spoken or heard anything between ’67 and ’84 and I get a phone call and he says, “Would I [you] like to go up and come to his [my] studio and see if we get on?” And I did. And we did get on and we still get on. Yes. He’s really good to me. I was there for 23/24 years and if it wasn’t good, I’d have gone. It was fabulous.

A mix of styles with the Amen Corner. You’ve got things like ‘Gin House Blues’ [released in UK as ‘Gin House’ although the DJ/promo copies had the full title] and then you’ve got the more pop side like ‘Bend Me Shape Me’ where you were kind of pushed in a more commercial direction?

Yes. Absolutely. ‘Gin House’ was the first single. I saw Zoot Money & His Big Roll Band. You know, Georgie Fame, Herbie Goins & The Night-Timers, Alexis Korner would all come to Cardiff and play. Chris Farlowe & The Thunderbirds. And Paul Williams, the bass player with Zoot Money. His song in the set was ‘Gin House’ and I saw that and then we adopted that, Amen Corner. It was just three notes so we could all manage that and it did all right and then our second single was ‘The World of Broken Hearts’. I really like that song but that didn’t really do that well even though we tried to buy it into the charts− Not ‘we’ as in ‘I’.

But it’s common.

Yes. So we bought it in thinking it was going to go but, even buying it in, it got down to the lower 30s, I think, and then our manager suggested we have a look at this song ‘Bend Me Shape Me’ − which I did not like − by the American Breed. It was already a hit in America but he said, “Give it a go. What do you lose?” So I had a piano riff that I pinched off Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, ‘Live at the Whisky a Go Go’ I think it was called [the Robinson-penned ‘More, More, More Of Your Love’ − the final track on their 1966 LP Away We A Go-Go]. And the piano riff went− [mimics the opening bars of ‘Bend Me Shape Me’]. So it’s nothing original and I put that song to that piano riff which I pinched from Smokey Robinson and kept the chorus, obviously. I didn’t like the brass on it. We never had a trumpet player. The brass was put on when we were away and I didn’t like it at all. Reminded me of Herb Albert and the Tijuana Brass who I like, by the way, but that’s not the point. They did it when we weren’t there and I threatened to quit, “If you release that−” and all of that but it became successful and I liked that I like that so we started to follow that path but, up until then, ‘Gin House’ was the only blues number in the set. Every other song we played Amen Corner was a soul number, going on Stax/Atlantic − not so much Tamla [Motown]. We might have squeezed in a couple of those but, generally, we were a soul band and that was it.

I’ve had Blue Weaver on the pod before and he told me in great vivid detail. ‘(If Paradise Is) Half As Nice’ is a song that won’t go away. It’s got a bit more of a timeless, ballad feel. Was that number one as well?

Yes it was. I found− Well, I say I found− It was given. I think Alan Jones was the connection. He turned up one day in the house when we lived on Harrow on the Hill. La Regazza 77 [‘Il Paradiso Della Vita’] was the single and it was ‘Half as Nice’. And if you ever get hold of that copy and listen to it, it’s note for note what we did. We just copied that record except it had me singing on top. That was the only difference. And I still play that song now and I love it. I absolutely love it − [it’s] part of the set. I usually leave it to the end because a lot of people that come to see me basically want to hear that song and I figured, if I play it in the beginning, they’ll bugger off in the interval, so I leave it to the end. So they have to wait, you know. Because Amen Corner was only three years of my life. My solo career with A&M was only three years. Man, I’ve been playing guitar with people for 24-26 years and that’s what I do. That’s how I made a living. I didn’t make a living from Amen Corner or from A&M.

You were saying about living. I think you had management difficulties as well?

Oh God. Oh yes. They certainly− We’d gone in at a certain level and we were passed around at that level and then finally ended up we were sold to Andrew Oldham with Immediate and then he went into liquidation, put himself in as the biggest guy who’s owed the most money − and just a total mess. Split up Amen Corner and just got rid of it. Got rid of those people. Best thing we ever did. We never got the money but, had I got the money, I wouldn’t have done anything good with it. I wouldn’t have had anything sensible. I would have just had further to fall because I was definitely on my way down.

So Fair Weather, a big hit with ‘Natural Sinner’ as an example. That was a way of casting away that Amen Corner?

Well, basically, it was. We broke up Amen Corner because that was the name that was going to be sold on by Andrew Oldham to EMI when they went into liquidation. So, put an end to that. And RCA Neon [the brainchild of Olav Wyper who, a few years earlier, had also been involved with the formation of the Vertigo label; Olav knew Andy from Andy’s days as Rockfield’s house guitarist/studio engineer] were prepared to give us money to pay off our debts which is between £10-£15,000 in 1969. So we took the money, paid the debt off and ‘Natural Sinner’ was a hit [albeit released on RCA Victor in the summer of 1970, a few months before Neon was officially born with the release of the Fair Weather album Beginning From An End in March 1971]. I bring that in every now and again into the set. It’s not always in there. And that only lasted a couple of years, two at the most I think. And then I just went home back to Wales for a couple of years and then came back up to A&M in ’74 I think it was. I went off to San Francisco and then Nashville and recorded Spider Jiving. I really liked Spider Jiving and I love that album.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aDuyUJXz0QU

You played with some fantastic musicians for Spider Jiving didn’t you?

Ohhhh! Well that was Elliot Mazer [percussionist] right. I got introduced to Elliot Mazer at A&M. They were sending up people and ideas for me to have a producer and Elliot was one of them. We started talking and he said, “Would you come to San Francisco?” And I went − because The Streets of San Francisco were big then and I used to watch that, Michael Douglas and Karl Malden − and I thought Yes, San Francisco would be good because he had a studio that he used in San Francisco. So I said, “Yeah. Of course I will.” So I went there. I got up, landed for a day and I thought I was going into a studio and I had to wait while he was finishing off Gordon Lightfoot, and when he finished off Gordon Lightfoot he’d had− In America at that time there was this thing about biorhythms and he had his biorhythms done and he went, “It’s looking pretty bad for me now for the next three weeks. I think you should go back home.” And I went, “I’m not going back home. I’m staying here ’til we do this thing.” And eventually we went in the studio and we were nine days in San Francisco and three in Nashville. ’Cos Elliot had also worked on the Area Code 615 album, so we had them. We had the Memphis Horns, we had most of Area Code 615 on there. Fabulous musicians. It was a fantastic time. Unfortunately I still haven’t paid back what it cost, but there you go.

‘Reggae Tune’ [from Spider Jiving] was a big hit in that period wasn’t it?

Yes. Well it was a hit. It was a top 10 hit. And originally it was a country song. In fact when I play it live now I play it− I sometimes start the show with just me playing on acoustic guitar and picking that song. Denny Seiwell was the drummer in the band then. He had been on ‘Live and Let Die’ with Paul McCartney because he was in Paul McCartney’s band [Wings] and we started talking and I said I wasn’t really fond of the song but I love that reggae bit in it and we started playing ‘Reggae Tune’ and he started playing that reggae beat. When we finished the track, because the chorus was “OH Shana. OH Shana. Eh…” he just said, “That reggae tune” and that’s how it became ‘Reggae Tune’. It was written down as ‘that reggae tune’.

And the hits kept coming, I think, from your next LP. There was ‘Wide Eyed and Legless’.

Yeah. The hit kept coming. I had a lot of air play with ‘Booga Rooga’ − and ‘Champagne Melody’ was another one, but in truth, ‘Wide Eyed’ did well. It struggled at first. I think they released it in the summer and then released it again more sort of Christmas/November time/winter time and it took off. And I play that now too and I’m really glad I’ve got those kind of things in the arsenal, if you know what I mean, just sticking around.

You were working with Glyn Johns at that time weren’t you?

Yeah. Man. My career! The people that I’ve worked with− For me, it’s about who you know, and I happen to know Glyn Johns as a real good friend too. So, whether it was Eric [Clapton], whether it was Joe Satriani, whether it was The Who, whether it was Stevie Nicks, Linda Ronstadt − the list went on. He’d sort of say, if he was doing anything, “Oh. Let’s get Andy in.” The ARMS tour with Ronnie Lane, 1984. I was staying with Glyn, and Ronnie Lane had been on the phone to Glyn saying was there any chance he could put something together to raise some money for these Hyperbaric Units? Because Ronnie had MS and the Hyperbaric Units, if they put them in, it seemed to work for them. And Glyn went, “Yeah. All right then.” I was sitting by Glyn’s pool and he went, “You’ll do it, won’t you Andy?” and I went, because I wasn’t working by then, “Yeah, of course I will.” Next phone calls are with Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, Eric Clapton etc the full list. So, yeah, my connection with Glyn − apart from being the fantastic producer, and I love the sound that he gets − he came back for Sweet Soulful Music as well. Another real good friend and a fabulous producer.

And another artist that you’ve worked with is George Harrison and he tried to get you involved in some of the solo work in the 70s, didn’t he?

Not so much in the 70s, no. We knew each other because we’re both Ry Cooder fans. I’d seen him at a few Ry Cooder concerts, stuff like that, and it was in the 90s. I went to Japan. It basically was Eric Clapton’s band and I got sort of brought into that band at that time and we did a couple of months in Japan playing live with George. That was pretty special. Then he did a concert at the Albert Hall for the Natural Law party and I got called for that. Then he was guesting with Gary Moore at the Albert Hall for two nights and he just phoned me up and he said, “You fancy coming up and playing with me?” and I went, “Yeah. Why not?” And then, halfway through the conversation he said, “It’s a long way isn’t it?” and I said, “I’m coming.” So I went to Friar Park and we stayed the night, then we went and played for two nights. Oh man, I loved him. He was good. My pal, I think is what we say. My pal. He was my pal. Yeah he’s a lovely man. Very funny. A fabulous slide player too and what a song writer. Talk about in a category all of his own. Nobody wrote songs like George and that’s a fact.

The stuff that he did. Even songs that arguably are slightly lesser known like ‘Old Brown Shoe’ are just classics.

Yes, it’s funny. I did watch a little bit of that Get Back thing and the beginning −he’s sitting at the piano and he’s just going [mimics the opening bars of ‘Old Brown Shoe’] and you’re thinking, “Yeah. That’s how songs start.” That’s it. Fabulous. And I love playing that song it. I had to learn his solo on that too. Oh man, that was tricky. But I did manage it. It’s on the Live in Japan album and I play that back every now and again and go “Yeah − you did all right Andy, you did all right.” And ‘Give Me Love’, the slide solo on ‘Give Me Love’. I had my work cut out for me I’m telling you.

It must have been quite moving at The Concert for George as well?

Oh staggering. Actually the three weeks of rehearsal were really precious. The night was a particularly spectacular event. Keeping in mind that, if you buy the DVD and you watch that concert, there’s no overdubs. There’s a few things that maybe have been removed and, if you’ve got six guitar players or something, you can’t have them all up there in the mix. But there’s no overdubs. That is live. That’s what happened on the night. That’s so special that band was that Eric put together. And the guy who did the sound on it was Ryan Ulyate. He did a fantastic job − with Jeff Lynne as well. It was beyond special. Magical, beyond belief.

Another artist you’ve had a an even more strong association with playing is Eric Clapton. How is it playing with such a remarkable guitarist like Eric?

It’s fabulous. He’s a lovely gracious, giving man. It’s not like a competition. I’m a rhythm guitar player. There aren’t many rhythm guitar players out there. And, in a setup like that, you need a rhythm guitar player like you need a goalkeeper in a football team. And I fitted in. I was the round peg in the round hole. Plus I worked for him like I’d like someone to work for me. I mean, I’ve been out front. I’ve found being a guitar player with other people was a fairly easy ride, relatively, as opposed to being the turn, being the one who’s worried about selling tickets or whether his voice is intact. All I had to do was do my job properly and focus on it and not take it for granted and be grateful. I’ve got to tell you, I was very grateful. He gave us the opening slot just recently at the Albert Hall and I was meant to do Europe with him as well but he got Covid and then I couldn’t go back out again. We’d played on his I Still Do album which was in 2016. So I’m back and forth every now and again and it was great to be back in his company and then at the Albert Hall [May 2022] we did like a reprise of the unplugged thing where I’d go up and play in the acoustic set too − and that was magical. You’ve got Nathan [East (bass guitar)], you’ve got Doyle [Bramhall II (guitar)], you’ve got Katie [Kissoon (vocals)]. We opened that door and there we were again and it was so easy. It’s so beautiful, so effortless.

Was that material like ‘Layla’ for example the acoustic [version]?

Yes. We did ‘Layla’, ‘Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out’ and we did ‘Smile’. I’d keep on wanting to do ‘Smile’. Gary Brooker, another fabulous friend who just passed away, actually. Gary and Eric were working on a version of ‘Smile’ and then he asked me, “Should we do ‘Smile’?” I said, ‘Yes.’ So I got to sing it with him. I got to sing harmony on a beautiful song. That is a fabulous song. And I got to take the solo too. So that was a lovely moment. I’ve been lucky. I’ve been very lucky.

And you mentioned Roger Waters earlier. The scale, even from the first tour that you did on Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking, must have been just something else.

Staggering. So we’re rehearsing and we’re rehearsing without any other visuals and then, all of a sudden, we get to America and they set up the visuals. It’s three full-sized cinema screens, back-projected, and at one point at Radio City Music Hall [in New York] I went out and listened to us − it was a lot on tape − and watched this thing and it was in quad too, in the hall – jets taking off, rain, dogs barking- It was spectacular and then The Wall in 1990. Well, to this day, I watched that thing every now and again. Not the new one. The new one’s fabulous. It’s got better graphics and all of that but that show in Berlin 1990, with the East German Army driving over the front of the stage and real helicopters coming in, and the Berlin Symphony − might have been the East German Symphony Orchestra as well − and have those cranes… the most amount of those bloody cranes − with great big lumps of cement hanging over your head − that have ever been put in one place at one time. Yes, pretty memorable. And there’d be more too. I did two world tours with Roger and one with Eric.

And then back to your solo material, Sweet Soulful Music was a sort of return to your song writing and getting a new album out?

Yes. I’d had 20, certainly at least 23 years, with Roger and 13, most probably, with Eric, playing other people’s material and I got to around 60 and I realized if I wanted to play what I wanted to play, as opposed to what I should play with other people. The only way I was going to do that is if I made my own album and went out with a band. I had enough songs hanging about and I went in with Glyn, recorded it in Battersea [Sphere Studios] and that was it. I continued, and I’m still on the road now from that point on. And I’ve been back with Eric and I’ve visited Roger in America. He flew me out to see a couple of the shows there and in Europe as well, so it’s been a fabulous experience and I’ve definitely benefited as a guitar player by getting out there and doing it.

Because ‘Hymn 4 My Soul’ is a song from that period that, again, won’t go away and I think Joe Cocker also did his own version as well.

Yes. Joe got hold of that. The reason Joe got hold of that too was Ethan Johns, Glyn’s son, produced that album. There’s the connection for that. They like that song so much. His album was called Hymn For My Soul and his tour that he went out with was called the Hymn For My Soul Tour so, I mean, there you go. You know I should retire now and go, “Right that’s it. We’re done.” And I love Joe’s version of it too. There’s a couple of great songs on that album, but I would say that wouldn’t I?

And then to close, just to mention your new album as well − Flang Dang. There’s just so many songs that you can pick from that and, again, they’ve got that similar theme that we were discussing at the start. I mean ‘Ska 67’ has got that great line “I ain’t waiting for things to come my way.”

Oh yes. “I am waiting on for things to come my way.” Like I say, they don’t come easy, those things, but I do spend a lot of time− ‘Somebody Wants My Soul’. God. I mean the groove on that. And ‘Darker The Midnight’. I love that in fact, good grief, ‘Got Me a Party’. I made my demo of ‘Got Me a Party’− I filmed myself− A cousin of mine came in and in my front room I filmed a version of me with my demo. I played my guitar along with it. It’s hard writing a simple song and that’s a simple song. I like the lyric. I like the groove and I love the solo. The solo took me ages but it’s kind of got an op divider on it. Yeah, I’m proud of that album Flang Dang. And I like the title of the album. I love the album cover. I’m a happy budgie at the moment.

What was the inspiration for the title?

I was watching some blues documentary. A couple of old guys down the front and the one guy said, “Well, we don’t want any of that hoochie coochie, flang dang stuff.” I wasn’t going to do the hoochie coochie thing but the flang dang − I wrote it down straight away and I wrote it in big letters and then I coloured it in and I went, “I like that.” Just like Spider Jiving, La Booga Rooga, Be Bop ’N’ Holla, Mega-Shebang. You name it, something clicks and I go, “Yeah. Flang Dang. I like Flang Dang.” And it’s really good to be happy with what you’ve done because, no matter what happens, if nothing happens you go Well, I’m happy with it. If you do something and you think It’s not really up to what I want but I’m going to put it out and somebody knocks it for one thing and you go Well, I wasn’t happy with it anyway. Well, I’m happy with it, so, that’ll do. Whatever happens, I’m comfortable knowing there’s not a moment where I’m going, “I wish I’d done that.” Apart from the strings on ‘End of all the Roads’ but that couldn’t be, because that would take it away from the fact that I did everything myself except the drums. And, I’ve got to say, meeting up with Joe Jones, the engineer, was the perfect meeting for me. He was just absolutely fabulous. Keeping in mind, there is a lot of overdubs, there’s a lot of running back and forth, there’s a lot of just me, back and forth, and he was just phenomenal.

That’s great Andy. What a pleasure it is to speak with you and even greater pleasure to listen to your fantastic new album. I wish you all the best with that release and just to say thank you so much for your time today.

Jase, thank you. You know it’s been years since I’ve talked. Now, this album was done in 2019, and 2020 it was finished. So, yeah, I’m getting to talk and, like I say, I love it and thank you. Thank you for liking the album. I love it.

It’s a pleasure. Take care.

And you too. Thanks Jason.

Further information

Podcasts also available: Blue Weaver – Strawbs, Amen Corner and session years, Blue Weaver – The Bee Gees and Pet Shop Boys years, Phil Palmer − Eric Clapton guitarist

Acknowledgements

Transcript and extra research provided by Nigel Davis.

Copyright © Jason Barnard, 2023. All Rights Reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the author.