Al Kooper has been a legendary songwriter, record producer and musician for over six decades. Highlights include his work with Blood, Sweat & Tears, playing organ on Bob Dylan’s ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ and collaborating with countless artists. He has also written an autobiography, Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards, one of Bob Dylan’s 40 favorite books.

In this interview undertaken in June 2020 which is published for the first time, Canadian writer Mark Campbell talks to Al about his early days, experiences with Dylan, insights into songwriting and producing, and current projects. Al shares his stories with humor and honesty, revealing why he is one of the most respected figures in rock history.

How is it that you’ve managed to be there at the dawn of so many different things? Be it the first big rock band, urban blues, the festival concert as we know it, what is it about you that you were able to either put yourself there or jump into those situations and be part of that?

Well, at a very young age, I went radio crazy. And, so I listened to the new music, which was rock and roll, on the radio. But even before that, my mother played the Top 40 every week. It was a show that had the top 40 songs going from 40 backwards to 1. And I would always listen to that, and that was even pre-rock and roll.

And then, when people like Alan Freed came on, I jumped on that. And one of the best stories is when I went to buy my first record, obviously a 45, and—boy. Can I remember these titles? [pause] Oh. [laughter] I don’t know if I can. But I had a choice of getting a full-on R&B song, and the other one was an instrumental that was not particularly rock and roll. But I just liked it because it had a piano lead. And so I went to the store, and I had my one dollar, and had the two 45s in front of me. I had already listened to them, and I’m going, “I can’t decide what to get.” And I looked at the instrumental record, which was on Kapp records.

And then I looked at [laughter] the other one that was a pure doo wop record, and it was on the Whirlin Disc label. And I said, “Well, there’s no contest here which one I’m walking out with.” And so I bought the Whirlin Disc one. And that was the first 45 I ever bought. However, two days later, I bought the other one.

[laughter] So those two 45s kind of explain or give some sense as to your early musical taste or your influences or help you define your sound?

Well, my early musical influences were the radio. And being an only child, I was able to sneak one of the transistor radios, at the time which were brand new technology, and sneak it into my bed. And in the middle of the night when I would wake up, I would get under the covers and listen to it. I tell you, until my father bought a portable one and that was much easier. And that had a headphone jack, mind you, one headphone. And that was even better because I played it really loud, and my parents wouldn’t hear it. That, I think, is the key to my obsession.

So, in the words of Lou Reed, your life was saved by rock and roll?

Yeah. Totally.

I did have a chance to look at some of your biography, and I noted that when you were six, your parents would go to their friend’s homes. And you went on one occasion, and learned, within an hour, to bang out Tennessee Waltz on the piano?

It was Tennessee Waltz, yes.

Was that the first instrument that you gravitated toward?

Yes. There was no other instrument to gravitate to, as universal as a piano.

Right. Was there something about the piano that resonated with you? The sound of it or the keys and what they could do in terms of—

No. Just that it was an instrument I could touch and try and make noise with that was me being allowed to do that. And so I would do that. My parents would say, “We’re going over to so and so’s, do you want to come?” I said, “Do they have a piano?”

[laughter] And if they did, you’d go.

That was exactly the conversation. And, fortunately, a lot of their friends had pianos, so I would go. I don’t know how much this screwed up their visit, but finally, they got a spinet for me, maybe about six years later. And then, of course, I learned how to play the guitar. And, so now, I wanted a guitar. But I didn’t just want a guitar, I wanted one in the Sears Roebuck catalogue that was a solid body and was $40. Much more expensive than the piano my poor parents bought. [pause] As soon as I got the Sears Roebuck guitar, that was pretty much the end of the piano.

What was it about the guitar that appealed to you? Was it seeing someone like Elvis there, standing on the stage—

Well, there was that. Plus it was great looking. It was a solid body, black guitar with silver trimmings. And it was very thin because it was a solid body. It was just amazing looking.

And unlike a piano, I guess you could take that anywhere, and you’d have music at the ready.

Yes, which led to the formation of my first band, the Aristocats.

How old were you when you started the Aristocats?

Oh, probably, 13.

So almost like a pre-generative boy band, in a way? [laughter]

[laughter] Yeah. And then we rehearsed in, I think, the drummer’s basement. And we started playing temples and churches and stuff like that. And we got $40. So we each made $10. And that was something. And at the same time, through someone I went to summer camp with, they had a connection to one of the buildings in Manhattan where all the music companies were. And there were three buildings. There was the famous Brill Building which was 1619 Broadway. And then, there was one that was trying to imitate 1619 called 1650 Broadway. And then, there was a really old building that music people ripped it out a lot of the offices, and that was 1674 Broadway. And those were pretty much where most of the New York upstarts were at, those three buildings.

For instance, Leiber and Stoller were at 1619, [pause] later on at the company called Aldon. Al Nevins and Don Kirshner. Which became the company that had the most songs in the Top 10 on a continuous basis because they hired incredible song writers like, Gerry Goffin, Carole King, and people like that. And in the third building were people that I was soon to meet, the group called The Tokens. And they had hit records, but they also started producing records. And the records that they produced became even bigger hits than The Token records. So these are my surroundings, and I usually could only go on the weekends. But, thank god, there were things going on in these places on the weekends.

And so little by little, I wormed my way into some offices where they would listen to songs that I wrote or would have me play on stuff. And one day at 1650, they had a band that had just had a number one record which was The Royal Teens who had “Short Shorts.” And the guitar player was going to leave the group for some reason, and so they asked me if I would be in the group. I said, “Well, I can’t play every gig because I could work weekends, but that’s all I can work.” And so they did that, and when on Christmas vacation and Easter vacation and stuff like that, I was able to get more extensive work with them. But they still were juggling guitar players. And then, at first my parents didn’t know. I didn’t tell them the truth. [laughter] But then, they found out.

How did they take it?

They did not like it. [laughter] And that was the end of my Royal Teen-age.

Did that experience with The Royal Teens, was there something about that where you thought, “This is exactly what I want to do with my life?” Was it the fact that maybe—

Well, we played—one Easter vacation, we played an Alan Freed show at the Brooklyn Paramount for, I think, seven or eight days. You know, five shows a day. [laughter] And that was definitely—because all these famous people were on the bill, and there I was with all these famous people and it was fantastic. And I also need to point out that the leader of The Royal Teens was a guy named Bob Gaudio. And then he went on—what was that second group? It was gigantic.

The Four Seasons.

Yes. He went on with The Four Seasons, and that’s where I met Charlie Calello, who became my right-hand guy for much of my recording career. He was playing days with them and also writing arrangements on a lot of hit records. And he became a big part of my solo albums because we worked together very well. This is the formation of what would end up being my whole life.

But do you recall in that formation when you made a switch from being a pure musician to starting to write music, do you remember the genesis of that?

Well, I was writing songs, but they weren’t good enough to show around.

Little by little, they got a little better. And I found a place in 1650 where they would let me work and do the songs. At first, I worked at a recording studio in 1650, and I was just an assistant engineer. So I was learning that stuff which was really valuable. And then, somebody, one of the bigger places, publishing companies, liked a couple of my songs and so, they took me there. And then they put me with these two other guys that just wrote words.

Right. Were you at this point writing self-contained songs, or were you writing melodies?

I definitely wrote self-contained songs. They just were not so fabulous.

You told Terry Gross in your one interview, that I think the words that you used were “Lyrically deficient.” [laughter]

[laughter] There you go. But still I wrote songs. These guys were better, and I actually learned so much from working with them. So we became a team, and another company signed us to a weekly stipend. By this time, I had gone to college for one year and left. And now, I had a job right away.

And this team, the three of you, was the team that wrote “This Diamond Ring,” correct?

That is correct.

And that was—was it Irwin Levine?

Irwin Levine and Bob Brass. And, as I said, they wrote just the lyrics.

And so when we talk about “This Diamond Ring,” that music is yours.

Yes.

So do you remember how that song came about?

Well, as songs start getting recorded, albeit not hits, we saw that we could reach other people. And in my collection were some really good records that just weren’t hits. And when we wrote “This Diamond Ring,” we wrote it for The Drifters. It was actually an R&B song. And The Drifters didn’t do, but some other guy did. And he imitated on a demo. And so, it was originally an R&B song.

Sammy Ambrose did the first—

Yes. Sammy Ambrose is the record I’m talking about it. But if anybody knows their records because their last name is Ambrose or because they know my story. It was as far from a hit as it could have been. But he followed the demo pretty much. But, then, our boss gave it to the guy who produced the Gary Lewis record. And I remember coming to work one day, and my boss and I were in the elevator and he said, “I have a record that I just got in the mail here that so and so produced of “This Diamond Ring.”” I said, “Oh. Who did it?” And he said, “Jerry Lewis’ son.” [laughter] I said, “That’s a joke, right?” And he said, “No.” He said, “It’s not them. I’ll play it for you.” So we went upstairs, and he played it for me. And I hated it. Mostly because it was so white. Not to mention that so was I. And so, then it became number one in about two months. And they played it on, the group played it on The Ed Sullivan Show the week that it came out. That didn’t hurt.

Well, it must be odd to be associated with a song that you don’t like. Or, at least, a version of it that you don’t like that opens doors for you.

That’s better. I was just going to say that.

Yeah. Would you tell people that, “That’s my song. That’s not quite how I envisioned it?”

Only when it was number one.

Right. So until it was number one, you kept, maybe, a discreet distance from it. [laughter]

Yeah. That was the first time anything I had been connected with was number one. I also left out that when I worked with Aaron Schroeder which is where I went back to after we left the place where, I think, “This Diamond Ring” was. I don’t know. Aaron Schroeder had “This Diamond Ring,” so it was later in our life as a trio, the writers, Bob and Irwin and myself.

So we didn’t do that well when we were with the first publisher, but when we went with Aaron—at the same time that he signed us, he signed this kid, and I happened to be there for the kid’s audition. And Aaron asked me if I would stay and tell him what I thought. And so this kid with the long hair from Connecticut, white boy, came in and played the piano and sang these songs he wrote. And I thought he was great. I thought he was a great singer and a great writer. And so, when he left the room, Aaron asked me what I thought. So I told him that, and he said, “I agree with you. I’m going to sign him.” And that was Gene Pitney. So we began at Schroeder’s together and I was amazed when he recorded some of our songs.

And you had a hit with one of them, a Top 40 hit with one of them.

Yeah. Well, “I Must Be Seeing Things” was the biggest thing we had with him. But we had, also, probably about five or six other songs that were on various albums of his.

I know you’ve told this story many times, but not long after you had your first number one through “This Diamond Ring,” you wound up in the studio with Bob Dylan.

Yes, I did. This was because of my friendship with the guy that produced him.

Tom Wilson.

Yes. We became very good friends. And one of the places that I would go because you could see so many A&R guys was Columbia Records. Because they had a floor and all the producers were on that floor. And so that was something. And that’s pretty much how Dylan got discovered. And John Hammond Sr. discovered him, but he also discovered an incredible amount of people. Jazz people, as well as, rock and roll people.

And so, he’s probably the most erudite producer I’ve ever met. And our offices, when I went to work at Columbia, our offices were right next door to each other, so we spent a lot of time together. And he was an incredible person. So that didn’t hurt me either.

So how did it come about? Would he just invite you to sessions like this that he was doing, and it just so happened that he was Dylan’s session, said, “Hey, come on in?”

Of course, not. [laughter] Well, [pause] so I started spending a lot of time at Tom Wilson’s office, and I played him some folk songs I had written. And so he went in and did a demo of me, playing and singing the folk songs that I wrote.

And what was his opinion of them? Do you recall what [laughter] his opinion was of your folk songs?

Fortunately, no.

[laughter]

But hanging out in his office was very helpful to me, in that I could take some Dylan demos and abscond with them overnight and then, put them back the next day which I never got caught doing, luckily. So one day, Tom Wilson invited me to a Bob Dylan recording session. He said, “But you just have to sit in the booth. [pause] You can’t do anything.” I said, “That would be great.”

But you weren’t about to do that, right? You really wanted to get down there where the action was.

Yeah. Well, as I said, at the time I was mostly a guitar player. So I brought my electric guitar to the studio, and I was going to say to Tom Wilson, “Oh, I thought you invited me to play.” Like that. This is a 21-year-old at this point. So it started out, I was in the booth. I got the—the session was called for one o’clock, and I got there at noon. And I took out my guitar, plugged it in, and I was just going to say to Tom Wilson, “Oh, I thought he wanted me to play on it. I misunderstood you.” [laughter] But Tom Wilson had not got there yet. So about 10 minutes after I plugged the guitar in, in comes Dylan with another guy with similar hair. [laughter]

And the other guy is carrying a Stratocaster and it was in February, and he had no case for it, and it was snowing out. So there was snow on the guitar. So he came in and he said, “Is that your towel over there?” I said, “No.” He said, “Good.” And he took it and wiped off the guitar, and sat down and plugged in. And as far as he knew, I was on the session as well. And he started playing, and I went, “Oh my god. I can’t possibly pull this off.”

And that was your first encounter with Mike Bloomfield.

Yeah. So I packed up my guitar, left it in the studio, and went in the control room where I belonged. And about—now, the other musicians were all studio musicians. So Dylan and Bloomfield were the only people that were in my age range, really. Everybody else were old guys that played sessions all the time. So about halfway through the session, they moved the organ player over to piano. And I thought, “Hum. How can I get out there?” And, also, it was very important that he left the organ turned on [laughter] because it’s very difficult to start a Hammond organ. It’s a three-move situation, and I don’t know how to do it which I did not know. Although I had played organ before on sessions, but I didn’t know how to turn it on.

Do you know now?

Yeah. [laughter] Very well. So they took a break, and I walked out into the studio. And I looked at the organ, and I hit a note on it. And it was still plugged in and turned on. So I said, “This is good.” So I sat down at the organ, and I said, “What’s going on? I don’t even know if he can see me from here.” But a guy comes in and says, “It’s actually on the album, this lick.” And he says, “All right. This is song number blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. And hey, what are you doing out there?”

And all the other musicians start laughing because they kind of know me. Then Tom Wilson starts laughing, and he decides to let it go. So there I am at the organ, and I go, “Okay. Take one. What’s the name of this? “Like a Rolling Stone.” And so, three incomplete takes go by, and then they get one that we, actually, played all the way through. And it’s, like, six minutes long or something.

And you had never heard this song before you sat down—

No, fortunately there’s only four or five chords in it. And my ears are very good. So I can pick up something if I can hear it, and so that’s what I did, and I had already heard three incomplete takes in the booth. So the actual change in my life is that they moved the organ player to piano.

So at the end of the take they, Bob and Bloomfield, go into the control room to listen to it back. And Tom Wilson says, “If anybody wants to come listen, they’re going to play that back.” So I said, “Okay. I’m anyone.” So I go in the booth and I sit down, and they start playing it back. And after the second verse, Dylan leans over to Tom Wilson—and this is all where I could touch any of these people. Very small circle. And Dylan says, “Can you turn the organ up?” And Tom Wilson laughed and he says, “That guy’s not an organ player.” He said, “I don’t care, could you make the organ louder?” And so, he says, “Yeah.” And he turned up the organ, and that was the moment where I became an organ player.

It’s funny how many people, in the wake of you doing “Like a Rolling Stone,” sampled or copied your sound. The multi-vibrato variants.

That was incredibly humorous to me because it was based on ignorance.

[laughter] But it’s such a unique sound. I think, maybe, anyone else could never have gotten that. I think that in some ways, not really knowing something probably played to your benefit. You are a bit freer to explore a particular sound without being locked into what it should be.

Well, I mean, in retrospect—recently I got a copy of the multitrack of it. And I put it on the computer so that I could raise Bloomfield up and raise the organ up and stuff like that. I also have a recording of Tom Wilson saying, “Hey, what are you doing out there?” [laughter] And everybody is laughing. [laughter] So, I mean, to have that forever is a wonderful thing.

I know that you had talked about, I think, it was Maynard Ferguson’s band, and how it would just put a dent in your shirt. And you wanted a rock band that was capable of doing that. What was it about what he did or what his band did that set you on this road of creating Blood, Sweat & Tears?

Well, now, I have to bring up something else that I used to do which was—one of the great things about the club, Birdland, in New York was that if you were underage, you could go in there. And they didn’t put you in the back; they put you on the side of the stage where you could actually touch a musician in you were of that bend. [laughter] And so, there were hundreds of times that I went to Birdland before I was 18. And my favorite group was Maynard Ferguson’s band, in that time period.

After the club closed, when the musicians were packing up, I would hang out and meet the musicians. But Maynard was extremely elusive. But there were other guys that were really nice to me. So I would go someplace else they were playing, and I would go after the show and they’d say, “Hey, Al. You came to this one.” You know, or something like that. And I’m telling you, I was like 16 or 17. And I just said, “God, I would love to have”—to myself. “I’d love to have a band like this, but that’s never going to happen.” Because this was a 16-piece band. So I tried to do it with an eight-piece band. And that’s what I was trying to do. Except I was trying to make a rock and roll band not a jazz band.

But it’s funny, when I listen to that first album, it’s rock, but it’s not rock. It’s also gospel, there’s blues, there’s R&B, there’s jazz, there’s classical. It just sounds like all of your influences coming together, like crystalized in this one—

Well, also, I had the perfect collaborator, which was the producer, which I picked. Which was John Simon. And he had produced a friend of mine who was a songwriter for The Tokens. So that’s where we were able to meet each other. And he was a really nice guy, and we became friends. I had Fred [inaudible – may be Lipsius] who wrote the arrangements which were fantastic. It was exactly what I was looking for. And Bobby Colomby who was an incredible drummer. And Jim Fielder, I think he was playing with the Buffalo Springfield for a while, and we became friends. And then, when I was able to put this band together, I called him, and he came right away from California to New York.

And you had Randy Brecker, right?

Oh. Randy. Randy Brecker, yes. Well, that was because of Colomby, he knew Randy Brecker. So everybody had a friend, and we were able to do that.

It did feel like, listening to it, it was the crystallization of all of your influences. It was an all-encompassing work, and not just in terms of taking in some of the great emerging songwriters of the time, such as Tim Buckley and Harry Nilsson, but also it really seemed to showcase coming into your own as a songwriter.

Well, there were a few—maybe three or four songs of the Blues Project where I was getting better. “Fly Away” was a Blues Project song. And of course “Flute Thing”.

And that’s another song I wanted to talk to you about was “Flute Thing” because, again, here’s another example of a song that, I guess in some ways, paved the way for Blood, Sweat & Tears. You can kind of hear the genesis of that in that song, in terms of the classical motif and the fact that it has that kind of groove to it. Did it surprise you years later when it got discovered and sampled and—

“Flute Thing”?

Yeah.

Yeah. Any time I got sampled, it shocked the hell out of me.

How does it feel when someone takes a work like that and repurposes it, in a way? Are you comfortable with it? Does it [laughter] or is it—

Once I got to the bank.

[laughter]

There’s one, I can’t remember the guy, but a big R&B guy, sampled it, and [pause] I called him, and he said something like, “I’m paying 60G flat for that. If it sells for more, tough shit. That’s the deal, you don’t like the deal fuck off.”

[laughter]

I said to myself, “I love that deal.”

[laughter] So there weren’t any lawsuits or anything with it?

No. And that song really got covered a lot.

It did. In fact, what was it? Seatrain did it as well; did they not?

Well, yeah. And also, Andy Kulberg played flute on it [pause] on the Blues Project. So he wanted to do it with the next band he was in.

So it’s basically had a little life of its own over the years.

I really wrote—I did that so he could have a song he could play the flute on and be featured. That’s the whole reason that that came about.

But it must be strange to see a song like that endure the way it has. Did you give any thought to its longevity?

Well, when you’re writing a song, you don’t really think that way. You just try to do the best you can, and then you go. I’ve had other songs, on other records, that should’ve been much bigger that nobody ever heard of.

I was wondering with a song like “I Love You More Than You’ll Ever Know” which has been recorded several times, when you were writing that what was the genesis for that song? Was there anything that you had in mind when you sat down to work on that? Was there anything that was, I don’t know—was it divine inspiration? How did you come to write that song?

“It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World” by James Brown. I mean, personally, I love that record. That was one of the biggest records of my life. And I remember writing it. I remember when I lived on, whatever the name of that street was. I lived in the Village. I wrote it in about 2 and a half hours.

When you recorded it, do you remember anything about that experience? Like bringing it in and working through it with the band?

No. I think the real original part of it is the bridge. “I’m not trying to be any kind of man,” that part. That there was really no precedence for.

It’s funny, I remember the liner notes for that, giving a little nod to Janis Joplin.

Yes. We could’ve done a great job with her. And then you add Amy Winehouse.

Did you have any clue that it was going to be covered to the degree that it would be? When did you get a sense that it was going to become that kind of standard?

Well, [pause] I’ll tell you a story. I don’t know if I’ve told it before. But actually I told it on stage. Jerry Wexler, world famous Atlantic producer, called me. About a year after I left Blood, Sweat & Tears. And he said, I’m cutting one of your songs with Donny Hathaway. And I thought, “Oh my god, this is going to be my dream come true.” I said, “Which one are you doing?” He said, “Something Going On.” [laughter] I said, “Jerry, [laughter] you picked the wrong song.” [laughter] He said, “What do you mean? He loves it.” I said, “Play him “I Love You More Than You’ll Ever Know.”” So he said, “All right.” And he hung up.

And he called me back two days later. He said, “you were right.” [laughter] I said, “So you’re going to do both songs with him?” He said, “Don’t be so Jewish. We’re doing “I Love You More Than You’ll Ever Know.”” [laughter] So I said, “I’ll take that.” So then, about two weeks later, he called me, and he said, “We’re going to do it tomorrow.” He said, “You’re going to love it.” I said, “Okay.” So he sent it to me, you know, a demo.

So I couldn’t wait to put this on the machine, and it started and just went like… And the way he sang the first line, it killed me. “If I ever leave you baby.” You know, like that? I said, “This is great.” And then, they changed the words in the bridge. Not only did they change the words, but they made them stupid and then, I lost my temper. I didn’t even make it to the end of the playback. [laughter] I called him up. I called Jerry Wexler. [pause] And I said, “Why did you change the words to the song?” He said, “What are you talking about?” I said, “I can be president of General Motors.”

He said, “Al. A black person could never be president of General Motors.” [laughter] And I said, “You’re so fucking stupid.” And I hung the phone up. And I never heard—we never spoke for about eight years.

It’s funny because I know that I’ve heard other versions where people have sung, “I can be president. I can be queen.” And we’ve actually seen that we can, actually, have [laughter] Barack Obama as president. So it always struck me as strange as nobody kept as “I can be president of General Motors” because it just seemed like an odd and interesting lyrical choice on your part. Such a specific thing where people are usually, “I can be the king of anything. I can be the queen of anything.” But you went with that very specific thing. What motivated you to write that one for the song?

Well, I just thought what Jerry Wexler said. [laughter] A black person could never be president of General Motors. [laughter] But he didn’t understand those lyrics, god dammit.

[laughter] So my question to you is, when you hear someone, even if it is an altered version of a song of yours, do one of your songs. Does that have more cachet for you than hearing you do a song of yours on the radio or holding an album of your own in your hands?

As terrible as that lyric is, that he replaced it with, [pause] I wanted to say to him, but I had already hung up the phone, “Oh, I’m sorry. He couldn’t be president of General Motors, but he could be king of everything?” [laughter] It’s just a terrible lyric, in my humble opinion. [pause] And so I tell that story, or I told that story every time I played this song after that.

Is there a particular version of that song that you like? Or do you feel yours stands as the definitive version?

Well, I love [laughter] Donny Hathaway version, and I love the Amy Winehouse version until they get to that part. I wish I had met Amy Winehouse so I could have told her the correct lyric because she, obviously, didn’t hear it from the Blood, Sweat & Tears record. But they were dealing with different markets. So I understand why that happened. I’m sure Jerry Wexler wrote the line, “I can be king of everything” because no good lyricist would write that, boy. [laughter]

You also have an ear for a great song. And that’s, certainly, proven in terms of something along the lines of your interest in, for example, The Zombies. The fact that you advocated for them while you were at Columbia. The fact that you discovered Lynyrd Skynyrd. For you, what is it about a song that resonates? What is it that you find in a particular artist, approach, or style—

Somehow, I don’t think of it as an ability. I think of it as, everybody’s got taste of some sort. And, fortunately, my taste in music is extremely wide-ranging. I like a lot of white music, and I like a lot of black music. And so that’s what I do.

I think it was around 1970 that you did the score for The Landlord. That would’ve been, what, one of the first instances of someone with a rock and roll background getting into scoring for film. So the strange part was that it was Hal Ashby’s first film.

He had never done a film before. And Norman Jewison was the producer, and he didn’t particularly want me to do it.

[laughter] So how did you overcome that barrier?

Well, he gave Hal his head. He let Hal do what he wanted to do. But, I mean, he interviewed me; it was like a scene from a movie. It was hilarious. [laughter]

So what was it about you that he thought, “You’re the one?” What gave him that kind of confidence?

I wish I knew. But he was a fan, so that had a contribution. Being that it was his first film, I couldn’t really judge him from anything, but I spent a lot of time with him. And he was a very unusual guy. [laughter] And I enjoyed the time I spent with him. And I hoped that he liked the score. He put it out was an album which I didn’t think was a great idea.

Why was that?

Because I didn’t know how to sequence it or how to mix it really. I had no experience with that. And I don’t have a copy of it.

Did you watch rushes of the film?

Oh, I spent an incredible amount of time with him. And everybody really got along well, so that helped.

So you had basically, what, the scenes, the mode, those things that you were able to draw on to try and start to pull together the music?

Well, you have to—[laughter] Now, if you want to talk about that, the thing I did next was much more difficult. When there’s a show on every week.

Oh, The Crime Story.

Yeah. So you have a week to write it, record it, and there you go. That’s hard.

How much music do you figure you created each week for it? How many minutes? Do you know?

Well, it was different every week, of course. But I would say an average of between 35 and 40 minutes.

Was that the first scoring project you took on since The Landlord? I don’t remember if you had any credits between the two in terms of scoring for TV or film.

Well, I did some stupid films that I don’t even remember their names.

What was it about Crime Story that made you think, “Well, I’ll take this on, and then, see how it works.”

Well, that guy was a famous guy for films and TV. So I was—and he came to me, so I was flattered. [pause] And I think that, if my memory serves me well, he wanted Todd Rundgren to do it. And I think Todd Rundgren did two shows and didn’t want to do it. I did two years of that, and I did for two years. And that’s as long as the show lasted. But I loved doing it, and I worked with Charlie Calello, again. [laughter] And we had a great time. I worked from 7 at night to roughly 5 in the morning. And then, he came in and worked from 9 to 5. And we divided each show up. And he wrote half the cues, and I wrote half the cues. And then, I mixed everything.

Would you have kept with it if it had gone a third season? Or [laughter] were you pretty much burned out by the end of the second season?

Well, we knew it was over a couple of episodes before the end. But while we were doing it—it was really hard work. Probably the hardest work I’ve ever done.

Speaking of your demos, I think you sent us one called “A Frozen Heart”. When did you write that?

Probably about 20 years ago.

When I listen to it, it sounded like a very sarcastic Christmas song. Like a holiday season song.

Well, when I first moved into this house that I live in now, [pause] after I moved in, I found out that the house to the left of me on the block was a place for mental people. Like a recovery place.

So I got my first keyboard to put in the house, and I put it right underneath the front window that faces out to the front of the house, and it was wintertime. And I pulled the shade up, and there were people from that house having a snowball fight in front of the house. So I sat down, and I went, “Mental patients throwing snowballs live right up my street. They have got me trapped inside those ancestors of creep.” [laughter] And I said, “I love that.” And I listened to it again, and I said, “You’ve just stolen the melody of another song.” [laughter] [pause] And I said, “Bus stop, wet day, da, da, da, da, da, I don’t know.” It was a complete steal. [laughter] And I said, “Damn, I love the lyric.” I said, “Well, that’s bus stop, wet day—that’s going up. What you did it and went down with the melody like—mental patients throwing snowballs live right on my street.” [laughter] And I changed it to that, and I kept the song.

Do most songs just kind of come to you like that in terms of you observe something and it’s instantaneous thing or—

It really comes from whatever. That’s a great example of—I happen to love that couplet lyrically. So, I mean, I didn’t know where the song was going to go after that. But I kept writing it, and I wrote it rather quickly. But when I did the demo in the basement, it got much better.

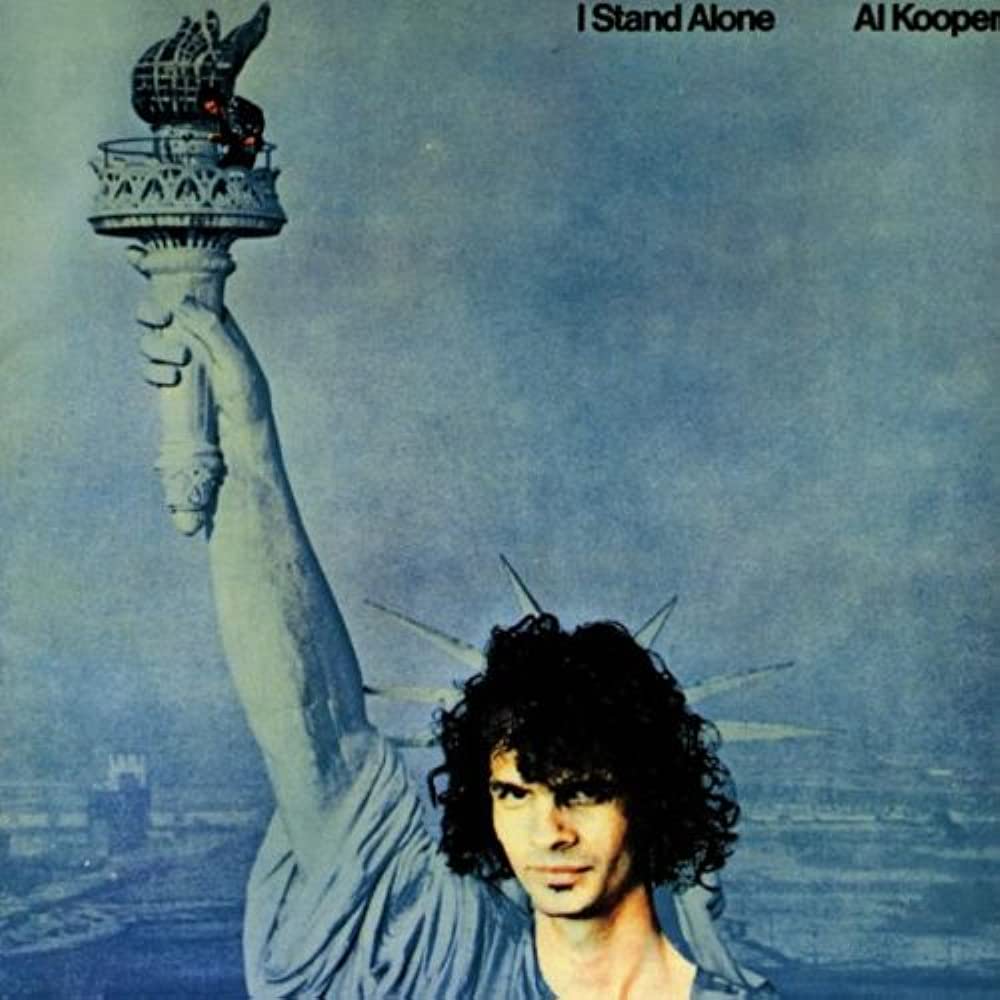

It seems like you have a very good sense of humor about yourself, about your music, just based on your album covers. like Act Like Nothing’s Wrong and I Stand Alone. Even, as I said, some of your lyrics have a kind of a wink in them. Is that something—is that kind of part of your musical language, that sense of humor? Do you find that it comes through a bit? Even in “A Frozen Heart”, I find that there’s that element there too.

Well, I mean, I love that Columbia Records, no matter what I asked for, they let me do it. [pause] I got a chance to work with unbelievable people. Photographers, illustrators, Norman, fucking, Rockwell.

Yes. That is one of those things that we need to talk about. [laughter]

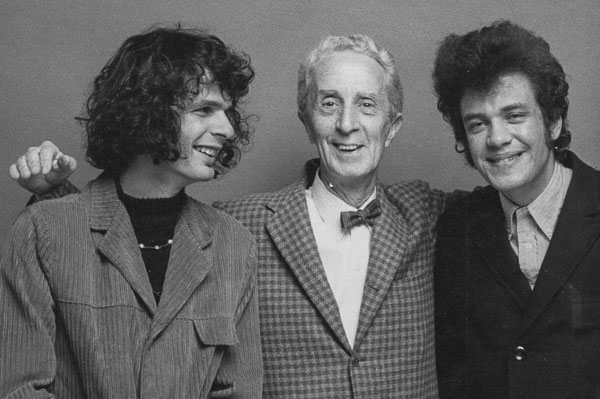

I didn’t know. I’ll tell you what made me think of it was we were having trouble coming up with a cover. [laughter] So the last complete thought we had was we were going to shoot a doctor picture of me and Bloomfield stepping off the Golden Gate Bridge. [laughter] That was what we had at the time. That’s what we were up to. So it was Sunday afternoon in late fall, and I was sitting and watching the Sunday football game. You know, the pro game?

Yes.

On TV. And I said, to myself, “Here I am. Look what I’ve done. Look what I could do. And, where am I? I’m sitting at home like everybody else, watching the fucking football game [laughter] because it’s the thing to fucking do on Sunday. It’s really entertaining, and it’s American.” I say, “It’s just like Norman Rockwell.” And I went, “Oh. Oh.” So I got on the phone and I called up the art director at home, and I said, “Let’s get Norman Rockwell to paint me and Bloomfield for the cover.” That’s the story of how I got to that. I said, “Can you get Norman Rockwell?” He said, “I can.” I said, “Let’s do it. It’s 10 gloms now.” And that’s how that happened.

How does it feel to know that he, apparently, said you were one of the most interesting people he had ever painted? [laughter]

Well, I bet we were. [laughter]

So he came and took your photograph.

Yeah. And, of course, at that point, nobody objects. And I had a photographer there, I forget who it was, but a big-time photographer. And so that photographer shot us as well. But, then, I discussed it with the art director, I said, “Well, he took every one of those paintings he did. Why should we stop him now?”

Oh, and then he invited me to one of his openings which was somewhere around Radio City Music Hall. So my wife, at the time, and myself went. And people would look at us really weird because we were dressed for rock stars at the time. And then he came in, and he saw me, and he said, “Come. Come sit with us.” So I said, “Sure.” All these people were going, “Who’s that?” [laughter] And then we went downstairs, and he took off his coat and hung it up and he said, “I just really wanted to see you again.” And he said, “I hate these things—

The galas?

Yeah. I said, “Geez, I don’t blame you.” [laughter] And that’s why I loved him. He spoke the truth and he painted the truth with style and grace.

I would say the same of you though in terms of your musical career and your thoughts about people that you’ve encountered. There does seem to be that same kind of mindset about you.

Obviously, I can’t think like that. But I think—I mean, I’m very happy with my biography because I wanted to do so many things, and I did as many of them as I could.

But your muse is still active, correct? You still get little flashes that become songs. You’re still doing demos.

No, that’s why I really want to get that box set out because it’s really something. I do have this one song that I co-wrote with Felix Cavaliere.

From The Rascals.

And he sang the demo. I did all the music, and he came in and put the vocal on. And it’s fantastic. [pause] And it belongs there, and that’s what I think about those, I call them 99 songs, I don’t know how many there are. But there are certainly less than 99.

Well, certainly, you’ve created some songs that have endured. You’ve created songs that, I think, are on par with any great songs that I could name. And I think it’s a really strong body of work that you should be really proud of. And I think, just hearing various vocalists, and even your own versions are superlative, but just seeing how those have endured and have been covered, people have gone back to that well that you created of songs.

Well, I’ll tell you a funny story. Every six months, I get a statement from the publishing company, and it’s about a quarter of the size of a phone book. It’s extremely thick. And I don’t think that I’ve ever been able to go all the way through it. Of course, I just look at the first page, it tells you how much money they’re sending you. And it’s a beautiful thing. [laughter]

So I just found that this is a very crucial time in the life of a songwriter. If they’ve had the songs for, the period of a contract is 50 years, and now they become entirely yours. And you can make deals that are—of course, I don’t stand there with the astronomical songwriters, you know what I mean? Like Leiber and Stoller.

Yeah.

And Lennon and McCartney. But I stand with [laughter] someone who’s going to get enough money every year to not have to think about it. And then, when I pass on, that lovely sum goes to my son.

That must be a nice legacy to leave him.

It’s a beautiful thing.

Is there anything that we didn’t cover that you want to add?

Yes. But it’s not musical, but it’s helpful to this conversation. I think if you’re going to listen to this whole conversation, one should read the book. I think that’s even more important in some ways because I said everything in the book. And I didn’t say near everything here.

Further information

Mark Campbell is an independent writer and entertainment editor. This interview was undertaken for an unreleased podcast called “Words & Music By…” which was also co-hosted and co-produced by Michael Maupin, former magazine editor and screenwriter, currently working on a TV serial drama about record producer Guy Stevens and writing posts to Substack. With thanks to Mike for his additional assistance; editing by Jason Barnard.

Copyright © Mark Campbell and Michael Maupin, 2023. All Rights Reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the author.