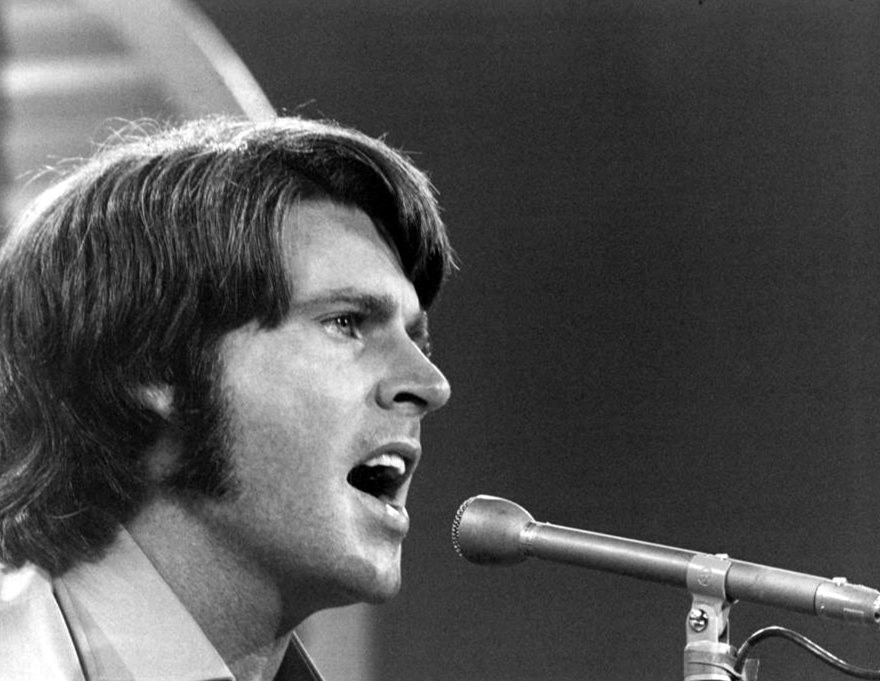

Rick Nelson performing on the CBS television program The Jim Nabors Show in 1970 (public domain)

By Scott Shea

In 1971, Americans realized they missed the 1950s. Having endured the breakneck speed of cultural trends during the 1960s, music fans longed for the simplicity and the innocence of those black and white days. The 1950s was the birth of rock and roll, and many of its legends were within reach. Most of the artists who provided the soundtrack were alive and well, sinking or swimming through the many musical changes that followed the arrival of the Beatles. The decade of the 1950s had become a soothing elixir that brought back clarity. Sure, it had its warts, but any struggles from those days gave way to memories of peace and prosperity and the movies and music of yesteryear served as a sort of time machine for so many.

One of the first people to seize on the ‘50s nostalgia trend was disk-jockey-turned-concert-promoter Richard Nader who in his 40-year career organized hundreds of rock and roll revival shows that featured superstars like Chuck Berry, Bill Haley & His Comets, the Coasters, the Shirelles and dozens of others. Nader went big by holding his inaugural show at the Felt Forum in New York City’s Madison Square Garden and the concerts grew larger and rowdier with each performance. By October 1971, he was on his seventh revival, and he was looking to diversify by bringing in different and bigger artists. A big one he coveted was Ricky Nelson, star of the ultimate 1950s family sitcom and performer of 32 Top 40 rock and roll hits from 1957 to 1963, including “Be Bop Baby,” “Hello Mary Lou” and “Travelin’ Man.” He was the next best thing to Elvis, and Nader had been chasing after him since he started this whole thing. To his surprise, Rick accepted, but, when it was all said and done, he wished he hadn’t. In the middle of his set, the crowd began booing, which sent the whole performance into a tailspin. Rick and his band finished their song and exited stage left, vowing never to take part in and oldies show again and surely asking himself, how did he get here?

America’s Favourite Rock & Roll Star

There was a time when the questions and the answers weren’t so difficult for the 31-year-old singer. Rick, or Ricky as many fans remember him, grew up in an entertainment family. His father Ozzie was a popular bandleader in the 1930s and 40s who scored numerous hits during that golden age, many of which included his wife Harriet as the featured vocalist. They married in 1935 and had two sons, David and Ricky. When the hits dried up, Ozzie refashioned his success into a family radio serial after three seasons of guest appearances on the Red Skelton Show. “The Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet,” aired on all three radio networks between 1944 and 1954 and found a permanent home on ABC in October 1949. After their successful 1952 feature film “Here Comes the Nelsons” gave Americans a cinematic view of the radio family, ABC debuted their television series that fall.

It ran for an incredible 14 seasons and featured silly, mundane plots like Ozzie’s quest for Tutti Frutti, Harriet preparing a soiree at her women’s club or either of the boys trying to impress a college coed. The humor was good natured and matched the tranquility of the decade and Ricky quickly became its breakout star. Billed as irrepressible, the youngster was a firecracker loaded with funny wisecracks, absurd hijinks and a classic ‘50s crew cut. In the middle of the fifth season, when Ricky was about to turn 17, rock and roll was the hottest thing in the nation, and he was all in on it. The bandleader’s son was the prime age for the music form recently kicked into the mainstream by Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Bill Haley and others. He would eagerly spend his allowance buying new releases at his local record store. Elvis’ Sun Records labelmate Carl Perkins was the one who touched him the most and, at age 15, he started tinkering around on the guitar. When a girlfriend laughed at him after he told her he was going to make a record, he accepted it as a challenge.

Of course, he had a big advantage. Not only was Ozzie the veteran star of “The Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet,” he was its producer, director and writer and was as connected as any entertainment executive could be. He was also a businessman and knew opportunity when he smelled it. He got on board quickly and shot a promotional film of Ricky singing Fats Domino’s “I’m Walkin’,” but the sell was harder than he’d envisioned. Only the jazz label Verve expressed interest and they threw Ozzie a bone by agreeing to a one-year deal, but their lack of faith turned out to be a blessing in disguise and displayed the naivety of the average middle-aged entertainment executive.

The show was never a consistent ratings bonanza, but it still got millions of viewers each week, and Ozzie knew this could give his show a boost and ignite his son’s singing career. And that it did! Ricky’s debut singing performance coincided with his Verve single debut of “I’m Walkin’” on April 10, 1957, which peaked at #17 in Billboard. The flip side, “A Teenager’s Romance” did even better, reaching #2. More importantly to Ricky, he was off and running. “I’m Walkin’” kicked off 18 Top 40 hits in a row, including the #1 hits “Poor Little Fool” and “Travelin’ Man.” In the beginning, his vocals were incredibly stiff, and the arrangements were safe and didn’t push his vocal range beyond its limit. But, over time, he developed a sweet, confident vocal and his weekly lip-synced performances were a highlight of the show that drew in younger viewers and inspired many a teenager to pick up a guitar and sing.

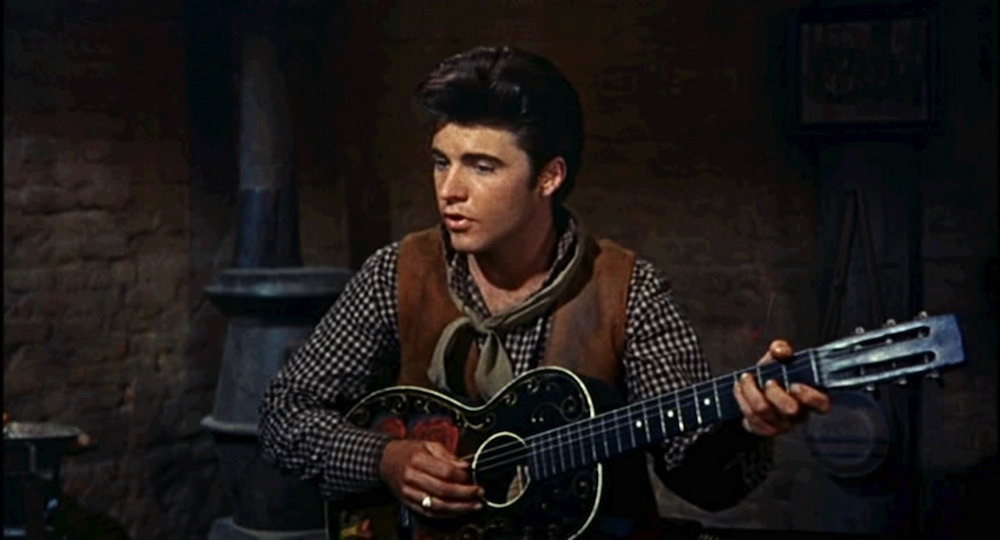

Because of the TV exposure and playing a series of sold-out state fairs, Ozzie was able to capitalize on his son’s initial burst of success by getting him out of his Verve deal prematurely after claiming Ricky was underage when he agreed to it. Ozzie was, after all, a graduate of Rutgers University School of Law and may have manufactured that loophole. In August, Ricky signed a five-year contract with the Hollywood-based independent Imperial label, the home of his hero Fats Domino, which was owned by industry veteran Lew Chudd. He sweetened the deal with a $50,000 advance and got the handsome teenager into the movies, starring alongside John Wayne and Dean Martin in the western opus “Rio Bravo” and Jack Lemmon in the comedy, “The Wackiest Ship in the Army.”

Over the period of his contract, Ricky built up a network of friends and collaborators who fashioned his unique sound, including songwriters Jerry Fuller, Baker Knight and Johnny and Dorsey Burnette, guitarist James Burton and arranger Jimmie Haskell. This incredible team made him a continuous chart presence from the late-1950s through the early-1960s. When his contract expired in 1962, a bidding war ensued, and Decca Records snagged him with a 20-year, $1 million deal. His first single, a dull slow ballad called “You Don’t Love Me Anymore (And I Can Tell),” only peaked at #47, and his follow-up, “String Along,” struggled to get to #25. The hits were stalling, and he wouldn’t hit the Top 10 again until his fourth Decca single, a cover of the 1930s Bing Crosby hit “For You” in early 1964. It would be his final trip there for eight years. The TV exposure at this point was moot and would become completely irrelevant following the arrival of the Beatles in February 1964. The once fresh-sounding punchy, up-tempo Jimmie Haskell arrangements, each filled with a compulsory James Burton guitar solo, now sounded formulaic and stale. His albums always included a gem or two, but, for the most part, were only a notch or two above an Elvis Presley soundtrack, and they all featured a predictable portrait of Rick on the cover that resembled a graduation picture.

Another Side of Rick

Overnight, Ricky, who now went by Rick, and most of his first-generation rock and roll companions were wiped off the charts completely by the Beatles and a cadre of British Invasion artists like the Dave Clark Five, the Rolling Stones, Gerry & the Pacemakers and Peter & Gordon. By 1967, “The Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet” was off the air and Rick’s career was in neutral. He attempted to change things up with consecutive country and western albums and even though they were a cut above what he’d been doing, they isolated many of his long-time fans and failed to endear him to the country music crowd. He followed those with two contemporary pop albums loaded songs from cutting edge songwriters like Randy Newman, Paul Simon, Tim Hardin and John Sebastian, but neither came close to charting. Producer John Boylan started writing with Rick and encouraged him to continue down this path and take advantage of the great resources around him in L.A. His 1967 album “Another Side of Rick” was his grasp at relevancy and created easy fodder for critics, but if listened to without prejudice, the soft, easy arrangements on songs like “Don’t Blame It on Your Wife” and “Promenade in Green” served as a roadmap for the direction Rick was heading.

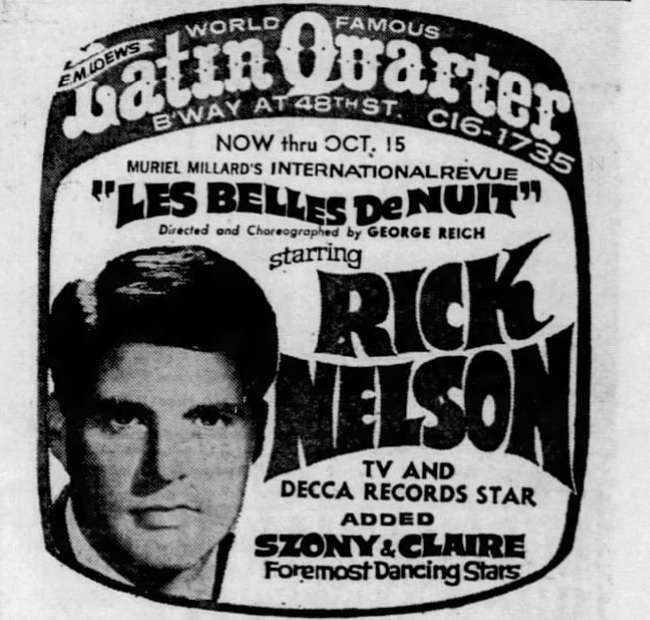

At the end of 1968, Rick made it back to L.A. after a tour of mostly unimpressive east coast venues like the Latin Quarter in NYC, the Three Rivers Inn in Syracuse and the Top Hat Supper Club in Windsor, Ontario supported by a trio of L.A. studio musicians. One thing was for certain, he didn’t want to continue this way. He needed change and fast. With a lot of extra time on his hands, he spent most days in his Malibu home working on songs, listening to Bob Dylan and taking in shows at Doug Weston’s Troubadour club in West Hollywood, which catered to country and folk acts. Taking in a Poco show one night in the spring of 1969, he was approached by their roadie Miles Thomas who recognized him underneath his fur parka and sunglasses.

“What’s it like being Ricky Nelson?” Miles asked him.

It didn’t initially endear himself to the chain-smoking ex-teen idol, but once they got to talking, bassist Randy Meisner’s name came up. When Miles informed Rick that Randy was leaving Poco, it piqued his interest. Not only was he one of the most talented young musicians in L.A., but he had a powerful vocal that stretched to the high notes with ease. Poco was one of the hottest acts in town and the group, formed by ex-Buffalo Springfield members Richie Furay and Jim Messina, was freshly signed to Epic and getting set to release their debut album. Rick was inspired by their blend of high harmony, delicate rock and country balance and the idea that they included a steel guitarist in a rock and roll band!

“Boy, I’d love to have a guy like that in my band,” Rick told him.

“I can do that for you,” Miles replied.

Meisner, who’d beaten out the talented Timothy B. Schmidt to land to Poco bassist spot, announced his departure after Furay wouldn’t allow him to sit on the album’s mixing sessions. Furay responded by wiping his contributions off the album completely. A few days later, producer John Boylan phoned Randy and asked him if he wanted to put a band together with Rick Nelson. It was a quick yes and he already had other players already in mind. From 1966 to 1968, he’d played with a group called the Poor who’d put out half a dozen singles with their final release being a one-off for Decca. He got in touch with guitarist Allen Kemp and drummer Pat Shanahan and made their way to Rick’s home to start working on songs and rehearsing. After several weeks of refinement, John Boylan talked Doug Weston into booking Rick Nelson and his new Stone Canyon Band, named after a road in the posh L.A. neighborhood of Bel Air, for a week’s worth of shows beginning on April 1st. Buddy Emmons sat in on steel guitar and, much to everyone’s surprise, they killed it. Shortly afterwards, Rick brought his new band into the studio and laid down several tracks, including a soft, countryfied version of Bob Dylan’s “She Belongs to Me,” which was released on August 25th. It was credited as Rick Nelson & the Stone Canyon Band and climbed up to #33. In Rick’s previous musical life, that would’ve been nothing to boast about, but in the competitive landscape of 1969, where he was still considered a relic, it was a feat.

Immediately after the sessions, Rick and the Stone Canyon Band set out on a five-gig intermittent tour of mostly smaller folk clubs. He was inspired by his positive reception at the Cellar Door in Washington D.C. on his 1968 tour and sought out venues that catered to music lovers. Beginning with over a week of shows at the Bitter End in New York’s Greenwich Village and ending with a couple of nights at JDs in Phoenix, Arizona in late October, Rick and his new band circumnavigated the country by station wagon. They wrapped it up with another weeklong gig at the Troubadour where this time they’d be joined on stage with new steel guitarist Tom Brumley who’d spent the last six years playing with Buck Owens. He’d worked himself sick for the country superstar and left the road to go into steel guitar manufacturing. He went into Rick’s Troubadour gig thinking it would be easy money for a week’s worth of shows and ended up playing with him for over a decade.

The Troubadour shows sold out and got great reviews. A new Rick Nelson had arrived, and the audience approved. His sets were filled with mostly new songs, but he incorporated new arrangements on some old favorites like “I’m Walkin’,” “Hello Mary Lou,” “Travelin’ Man,” “Poor Little Fool” and others. He was even joined on stage one night by fellow 1950s refugee Don Everly of the Everly Brothers who duetted on “Bye Bye Love.” Rick’s humor and self-deprecation were in full effect and endeared himself to his audience. Reminiscing about singing “I’m Walkin’” on “The Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet” back in 1957, he took light-hearted shots at the innocent age.

“It’s funny to me. I did it on the television show. I remember I had a tuxedo on, and I was in a gymnasium…you know, for a change,” he said through a chuckle to a giggling audience.

The stand couldn’t have been better, and it seemed like things were all at once new and back on track. But there was still more work to do. As a follow up, Rick released his most mature composition yet, “Easy to Be Free,” which he debuted on his short tour, but it only peaked at #48. Even a hippie-styled promotional video shot by his brother David couldn’t elevate into the Top 40, but it fully displayed his style shift. A 1970 release of his October Troubadour concert was his first album to chart since 1963’s “Rick Nelson Sings for You,” peaking at #54. Undeterred, he pressed on and release a string of quality albums that perfectly captured the L.A. sound of the early 1970s. “Rick Sings Nelson” came out in September and was exactly what the title suggested; 10 new songs composed by Rick himself. Billboard gave the album high praise, but it charted at a disappointing #196 and neither of the two singles cracked the Top 100.

Life on the road began taking its toll. After a grueling tour of military bases in Germany in the spring of 1970, where their long hair was easy fodder for servicemen, Randy Meisner quit and returned home to Nebraska to take a job as a parts man for a John Deere dealership. The tour was rough on everybody and the good vibes from a year earlier gave way to the realities of life on the road. But Randy’s retirement didn’t last. He was back by November. It brought a sense of relief to Rick as he was the heart of the band. Things ran harmoniously for the next eight months, and Rick and the Stone Canyon Band entered the studio again in April 1971 for their next album, “Rudy the Fifth,” named after the house brand champagne at nearby Rudy’s Liquor Store on Riverside Drive. This time around, it was a mixture of Nelson originals, a couple Bob Dylan covers and their funked-up version of the Rolling Stones’ 1969 #1 hit, “Honky Tonk Women.”

In June, near the end of the sessions, Randy accepted an offer to fill in for Linda Ronstadt’s bassist Mike Bowden at her gig at Chuck’s Cellar in Los Altos, California. Also supporting her that night were two other anonymous L.A. musicians, Glenn Frey on guitar and Don Henley on drums. Both had released albums with their respective bands, Longbranch Pennywhistle and Shiloh, on the Amos label but remained struggling musicians seeking their big break. Though they had no way of knowing it then, it was the very definition of kismet and the three bonded so well in such a short period of time that, by the time “Rudy the Fifth” overdubs were completed, Randy left to join his new friends and form the Eagles. Along with seasoned guitarist Bernie Leadon, they would go on to be one of the most successful rock bands of all time and Randy brought with him much of the country rock sensibilities he’d help develop with Rick. He didn’t leave his old boss empty handed though, recruiting friend Stephen Love who played in Randy’s band Gold Rush during his hiatus to take over on bass and backing vocals. The summer brought with it a lot of down time, but Rick and the band played a handful of dates at mostly local venues like Knott’s Berry Farm, Magic Mountain and the Festival in Santa Barbara, which served as a nice warmup for their fall tour in support of the new album. But, before they could do that, Rick had to confront his past.

The Garden Party

By 1971, the oldies revival was heating up and young and old alike were falling back in love with the music of the 1950s. But it never really left. On the West Coast, DJs like Art Laboe and Hunter Hancock kept the music alive through their “Oldies But Goodies” and “Cruisin’” LP compilations, which contained heavy doses of 1950s R&B, doo wop and rock and roll. The big three Los Angeles stations, KHJ, KRLA and KFWB, routinely dropped oldies in their playlists, as did Wolfman Jack on XERB whose show was broadcast halfway across the country from its 250,000-watt tower across the California border in Ciudad Acuna, Mexico. New York City, however, was the heartbeat of the oldies revival. Like its L.A. counterparts, WABC, WINS and WMCA dropped in the occasional oldie, but the much less powerful WADO exclusively played oldies at night on Alan Fredericks’ “Night Train” show. Much of his playlist was influenced by Slim Rose, owner of the Times Square Record Shop, which occupied a small, cramped storefront in a couple of different locations in the long chain of subway platforms underneath 6th Avenue and Broadway in Midtown Manhattan.

In early 1969, Columbia University graduate student George Leonard transformed the school’s longstanding a cappella group, the Columbia Kingsmen, into a commercial act renamed Sha Na Na who focused on 1950s doo-wop and teen ballads and dressed up like a gang of motley greasers. On August 18th, they were the penultimate performer for the Woodstock Festival in Bethel, New York, playing right before Jimi Hendrix who was a fan and got them on the bill. That same year, easy listening New York radio station WCBS-FM relaunched as a hipper, freeform format and brought in 26-year-old Gus Gossert to play doo-wop on Sunday nights. Much of his playlist featured the R&B harmony subgenre from the early part of the decade that has often been referred to by that name, which he has often be credited with as coining, but an acknowledgment he always rejected. One of his steadiest advertisers was Richard Nader, another twentysomething lover of oldies, who was making his fortune putting oldies concerts together.

Nader, a Long Island native, was an ex-disk jockey and a talent promoter who also loved music from the 1950s, bragging to Newsweek that he personally owned over 7,000 singles from first rock and roll era. Nader organized dances as a teenager and joined the Premier Talent Agency after his discharge from the Army in the mid-1960s where he booked artists like Herman’s Hermits, the Who and the Animals into New York venues. But he loved ‘50s music the best and was determined to bring it back. He was so passionate about his vision that he borrowed $35,000 to rent out the Felt Forum in Madison Square Garden to give these beloved performers the stage reminiscent of the Alan Freed concerts at the Paramount and Fox Theaters in Brooklyn back when the music was new. In two years, he staged six concerts that featured Chuck Berry, Bill Haley & His Comets, Bo Diddley, the Penguins, the Five Satins, Shep & the Limelites and many others.

For the latest installment at the 5,600-seat Felt Forum on October 15, 1971, Chuck Berry was again the headliner and Bo Diddley was there as well. Also on the bill were former Philadelphia teen idol Bobby Rydell, the Shirelles, the Coasters and Gary U.S. Bonds. Rick Nelson was a late addition and he only agreed to it on the condition that this show be billed as a “Rock and Roll Spectacular” rather than its usual “Revival” title. Rick had spent so much time removing himself from the shadow of his past that agreeing to this gig seemed out of character, but he justified it, telling journalist Todd Everett that “it would be good to be seen by that many people and that I could sneak in some new material.” The latter part of that rationalization would come back to bite him.

His set started off well enough, playing a slate of old hits like “Hello Mary Lou,” “Travelin’ Man,” “Poor Little Fool” and “Believe What You Say,” which had been regularly featured in their setlists since they first started playing live. For this occasion, however, they learned “Lonesome Town” and “Be Bop Baby,” which opened the set and got off to a rollicking start. Rick looked a lot different than he had on TV, with shoulder length hair and donning the styles of the day, including bellbottoms and a $2,000 purple velvet shirt. The change in style could be overlooked though. Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley had updated their look, as did most of the other acts, but there were most likely some unfriendly comments from a few alpha males in attendance that caught their ears. Minus the expensive shirt, Rick looked much like everybody else in 1971, but a far cry from the besuited, youthful, handsome singer in black and white from “Ozzie & Harriet,” with the clean-shaven face and perfectly quaffed pompadour. The arrangements of the old songs were contemporary, but most fans probably didn’t even notice. That’s not what did him in.

When all the old hits were done, Rick and the band launched into “She Belongs to Me,” his comeback hit from two years earlier. That’s when the low rumble began. The applause following his Bob Dylan cover was minimal. There was no place for the “voice of a new generation” at a 1950s revival. They followed that up with their arrangement of the Rolling Stones’ “Honky Tonk Women,” which they’d recorded for their upcoming “Rudy the Fifth” LP. Their version, however, featured Allen Kemp shredding his guitar throughout the song and sounding more like Edgar Winter than James Burton. In the middle of it, audible booing and heckling could be heard. It’s the most horrifying thing a performer of Rick and the band’s caliber could endure and an indictment of their performance. They got through it like professionals, bid the crowd good night and beat it off the stage as fast as they could with Rick muttering that he knew this was a mistake. Backstage, Rick and his bandmates were visibly upset as they went to pack up as quickly as they could and get the hell out of there. Some stagehands attempted to put them at ease by telling them that a couple of drunk audience members had gotten into a fight in the back rows during their set and the audience was booing the police who were pulling them out. It was after all the era of the counterculture and any police involvement was easily interpreted as brutality. But, although that might have been the genesis of the booing, it probably triggered other members to voice their disapproval of Rick’s new material and style. It would be a dozen years before he would ever play another oldies show.

Lemonade

The scrutiny was inescapable as the story was reported in just about every major newspaper. It looked as though all the hard work Rick had put into reinventing himself had blown up in a chorus of New York boos. How could he ever recover from this, and could he ever get beyond his musical past? But there’s an old saying that when life serves you lemons, you make lemonade, and, once the dust had settled several months later, Rick began the juicing process. Back home in Los Angeles, he got inspired in the middle of the night, ran downstairs to his piano and the music and lyrics began pouring out of him. Almost from the very beginning, it was called “Garden Party,” and it spoke of his experience that cold night in Madison Square Garden. Despite the poor sales of his recent albums, critics had praised his new self-sustained approach in the era of the singer/songwriter, but this new song was unlike anything he’d written, and it set the stage beautifully from the opening lines:

“I went to a garden party/to reminisce with my old friends. A chance to share old memories/And play our songs again.”

To the unknowing listener, it sounds like a Victorian outdoor party filled with music and gavotting gone horribly wrong, but it was an accurate portrayal of his Madison Square Garden disaster.

“I said hello to Mary Lou/She belongs to me. When I sang a song about a honky tonk/It was time to leave.”

Rick and the band recorded it in early May 1972 and gave it the ultimate soft country rock arrangement that sat comfortably next to anything put out recently by James Taylor or Glen Campbell, but the label didn’t pay it any mind at first. By 1972, Decca Records, which was in the process of changing its name to MCA, had seemingly forgotten that Rick Nelson was on their label even though, less than 10 years ago, they broke the bank signing him. Now, he was essentially an afterthought and farther down the ladder from breadwinners Elton John and Neil Diamond. But the incident at the Felt Forum got a lot of publicity and his cousin/manager Willy Nelson (not the country singer) met with top label executive Rick Frio to pitch the song as a redemption story. Frio bought into it and started making phone calls and, within hours, the MCA promotional team got fully behind it. The single was released in July and climbed up to #6 in Billboard and #3 in Cash Box by early fall, making it Rick’s highest charting single and album since “For You” back in 1964.

“Garden Party” marked the end of Rick’s Top 40 run, but not the end of his quality music. The success of the song opened him up to better gigs with higher booking fees, but the Stone Canyon Band wasn’t benefitting much from the residuals. When cousin Willy reneged on a promised pay increase, Allen Kemp, Pat Shanahan and Stephen Love walked out, hoping it would change hearts and minds, but it didn’t. They were promptly replaced, and Rick still had a rock in steel guitarist Tom Brumley. He and the second incarnation of the band kept up with the country rock sound until it started to get stale near the end of the decade and Rick gradually adopted the gentler rock sounds of the late-1970, which fit his vocal well. Songs like his covers of John Hiatt’s “It Hasn’t Happened Yet” and Bobby Darin’s “Dream Lover” should’ve been hits, but the marketplace was too timely and too apathetic to its veterans. There was precious little space for the old guard.

On December 31, 1985, while flying from Guntersville, Alabama to a New Year’s gig in Dallas, Texas, the plane Rick and his band were traveling in caught fire as it was in its final descent. The crew attempted to make an emergency landing in a field two miles short of the runway in De Kalb, Texas, but crashed after clipping some trees, killing Rick, his fiancé, Helen Blair, his band and sound engineer. Both pilots survived. Although never fully confirmed, the suspected cause was the plane’s faulty gasoline-powered cabin heater. Regardless, another 1950s music superstar died tragically and too young. Though he’s spent much of his last 16 years running away from his past, his initial achievements made him a shoo-in for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987, and although his hitmaking years were enough to qualify him, the second half of his career cannot be overlooked. It may not have been as hit-laden, but the hard work and determination of remaining a contemporary musical contributor was undeniable and his work ethic second to none. And the refrain from “Garden Party” has served as his epitaph.

“You see, you can’t please everyone, so you got to please yourself.”

I dig this auther. I always learn something more about an artist I thought i was already familiar with. I am now seeking out Rick’s later lp output. Scott always sparks the readers interest in the topics he writes out. Kudos to you…Mr. Scott Shea…I enjoyed the article.

The redemption of Ricky Nelson? It is so hard to get people to take Rick Nelson’s music seriously because that “little Ricky” image is impossible to shake. Fans at MSG in 1971 expected him to walk out with a crewcut, braces on, saying “I don’t mess around, boy”, it’s like if Beaver Cleaver had tried to be a rock and roll singer. People wanted him to be a boy forever, but like all of us – if we’re lucky, he grew up, grew his hair long, got serious about being a musician, and started writing his own songs. Forget “Be Bop Baby” and all those teenybop songs; Rick Nelson made some of the best pop/rock and roll records ever – “Hello Mary Lou”, “Believe What You Say”, “Lonesome Town”, “It’s Late”, “Just a Little Too Much”; even the songs on his albums were strong – his versions of “Shirley Lee”, “Milkcow Blues”, “My One Desire”. He had the best band and the best writers giving him material. And listen to those records with the Stone Canyon Band – “Easy to Be Free”, “She Belongs to Me”, “We’ve Got a Long Way to Go”, “Gypsy Pilot” – Frankie Avalon and Fabian never made records like those! The man deserves respect.