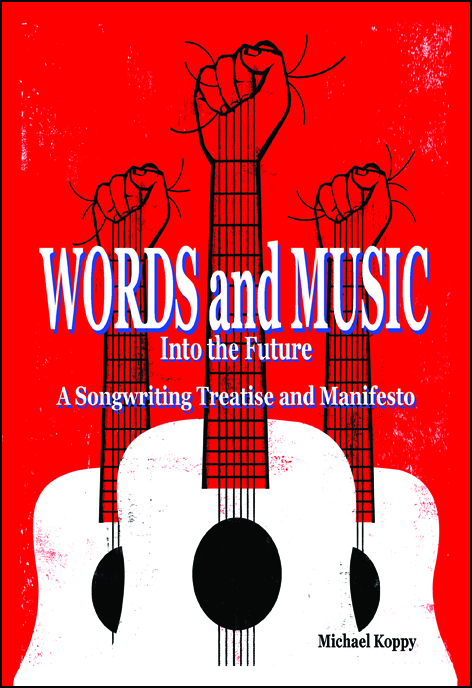

Michael Koppy’s new book ‘Words and Music Into the Future’ examines the state of popular songwriting. In it Michael presents the case that we have been force fed poor songwriting so Jason Barnard speaks to him to explore this viewpoint.

What drove you to write ‘Words and Music’?

Constant dismay at the poor quality of writing I’ve encountered—we all have encountered, whether fully aware of it or not—in popular songs. Standards are SO LOW that just about any nonsense, incompetence, or even downright gibberish can be not just tolerated, but lionized. (See the epigraph from Marika Lundeberg that introduces Chapter 18, on page 71. I think she speaks for all intelligent listeners in her apprehensions about what she’s hit with in pop songwriting.)

What do you think sets it apart from other musical critiques?

The views I present are certainly not unique, nor are they that radical, really—except insofar as one simply doesn’t see them martialed in organized manner. We have all been so ‘dumbed down’ by the crap we’re given that our abilities to even reject out-and-out stupidities and presumptions have been severely crippled. I point out that the emperors really AREN’T wearing anything, and do so (I think) fearlessly but evenly; without rancor—and often even with generosity. But I am unwavering in my determination to expose incompetence and industrial pollution—while similarly, absolutely determined to offer specific remedies and avenues for progression.

You dissect Don McLean‘s ‘American Pie’ in Chapter 1. Was it important to open with a song universally lauded?

Yes, indeed. As noted at the middle Page 30, it’s really important to discuss songs that most readers know and know well—that they’ve heard a zillion times. And, along with “American Pie”, in the first three chapters I also address four other songs that have been universally lauded: “Come Together”, “Forever Young”, Small Town”, and “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down”. See the first paragraph on Page 22 for more on that thinking. Anyone can dismiss a song most people think a failure. We need here to point out, to underscore, that even so many of the Most Revered Songs are in fact ultimately just rubbish, insults to our intelligence.

What other lyrically praised tracks do you feel don’t hold up and why?

This is a tough question; but a tough question because it’s such an easy question. One of the primary points of the whole book is that we are INUNDATED—inundated by and inured to—so much utterly abysmal writing in popular songs. While I do indeed cite the occasional first-rate piece (see those in analyzed in Chapter 41, for example) or song that is uneven but still noteworthy (see “These Days” and “Me and Bobby McGee in Chapter 40) we are dealing here with an artform in which ANYTHING goes. And so what most often ‘goes’ is anything that is insultingly inept, often simply idiotic. And—something also addressed throughout—rather than being summarily dismissed, the preposterously bad quality stuff is treated respectfully, often even reverentially, by critic and public. But—in defense of that public, if not of the critic—what alternatives are they/we given? More, what else are we allowed to even EXPECT?….

However do you agree with Jarvis Cocker who wrote about reading lyrics in isolation: “The ways in which you get to a final destination are really quite irrelevant; the important thing is when somebody puts something on the record player, what effect it has on them, and sometimes, actually knowing how something was done, can undermine that. I’ve always had that feeling, that’s kind of partly the reason for that thing that I always put on the lyric sheet, the ‘Don’t read the words whilst listening to the record’, because to me that makes it seem forced and the words are really kind of shoe horned into place.”

Yes, well, Mr. Cocker here advances solipsistic navel gazing as comprehension and communication. WORDS HAVE MEANINGS. That the ‘words are often shoe-horned into place’ is most certainly true—but that sure’s hell AIN’T NO DEFENSE of the character and use of those words. And, as I most clearly note in many, many places throughout the book, we each and all have our undeniable weaknesses via nostalgia, personal aspiration, need for comfort or validation, OR SIMPLY GETTING AN EARWORM STRUCK IN OUR UNGUARDED HEADS. All understandable—we’re all human, after all—but also all far, far, from providing any justifiable rationale for therefore jumping to a conclusion this or that song is therefore great or even good art.

Why don’t you like the term ‘artist’?

As (I think, no?) is rather clearly pointed out by Chapter 8, ‘artist’ is not just a descriptor but a magnifier—the term bestows an implied exaltation that actually DIMINISHES creative achievement (by mystifying it) concurrent with validating spectacular industrial affectations and tawdry presumptions. Really, this question is fully addressed there in Chapter 8, and it’s a quick read.

What do you feel are the best and worst examples of words and music, and why?

Let’s speak generally, because I point out so many specific worst cases and many best cases already. (Well, I do also already address the matters in general, and throughout, but nonetheless…) A ‘best case’ song delivers information that intelligently, deliberately makes us think or feel in a new way. Note the words ‘deliberately’ and ‘intelligently’. If we IMPUTE meaning where, in all reasonableness, it really doesn’t exist; if we ASCRIBE insight to wordage that first requires a kilo of marijuana to get us there, we’re NOT talking about a well-written song. We’re talking about our own wishes and desires for what we’d LIKE the song to deliver.

You’re especially critical of Bob Dylan – what are the most common misconceptions about his writing?

(I’m glad you restrict this to his writing, because when taken as a package—not just writing, but self-entitlement, dishonesty, contempt for women—I often characterize him as ‘“The Donald Trump of Popular Music” or “The Donald Trump of Songwriting”.) He’s simply a very poor writer. As I think is written in two places in the book, ‘one could never reasonably put the words “Bob Dylan” and “articulate” in the same sentence’. He evinces little command of language—just because one pours on MORE words is not a proof that one is doing so effectively or even coherently. Fairly, accurately addressing Dylan’s general incompetence is important because it exposes the entire rickety façade of industrial popular music. We are presently NOT in a good place!….

Are there any songwriters around today who you feel can improve its standard?

I assume you ask for specific names here—but I decline to burden him, her or them with what I might hope he, she or they might accomplish if properly disciplined and providentially inspired. I occasionally cite this or that professional—note I don’t say ‘artist’—in the book as doing some admirable work. But it is NOT the person, it is the WORK that matters. Naming names, facile an agency as that is, inexorably leads to fandom, and ultimately, to idol worship. We all do it, all the time, in print and conversation, of course, but in reality it’s a slippery dodge for precision. The paragraphs on Page 43 charitably address this matter at some length. I will sum up here by directing you to Chapter 58 (Page 299) for general thinking on how songwriters can begin improving their work—and Chapter 55, perhaps, (Page 267) to address specific examples of exalted ‘artists’ (Bowie, Neil Young, Cobain, Dylan, etc.) who pride themselves on NOT improving their work.

Thank you for your interest.

For more information see: michaelkoppy.com