By Scott Shea

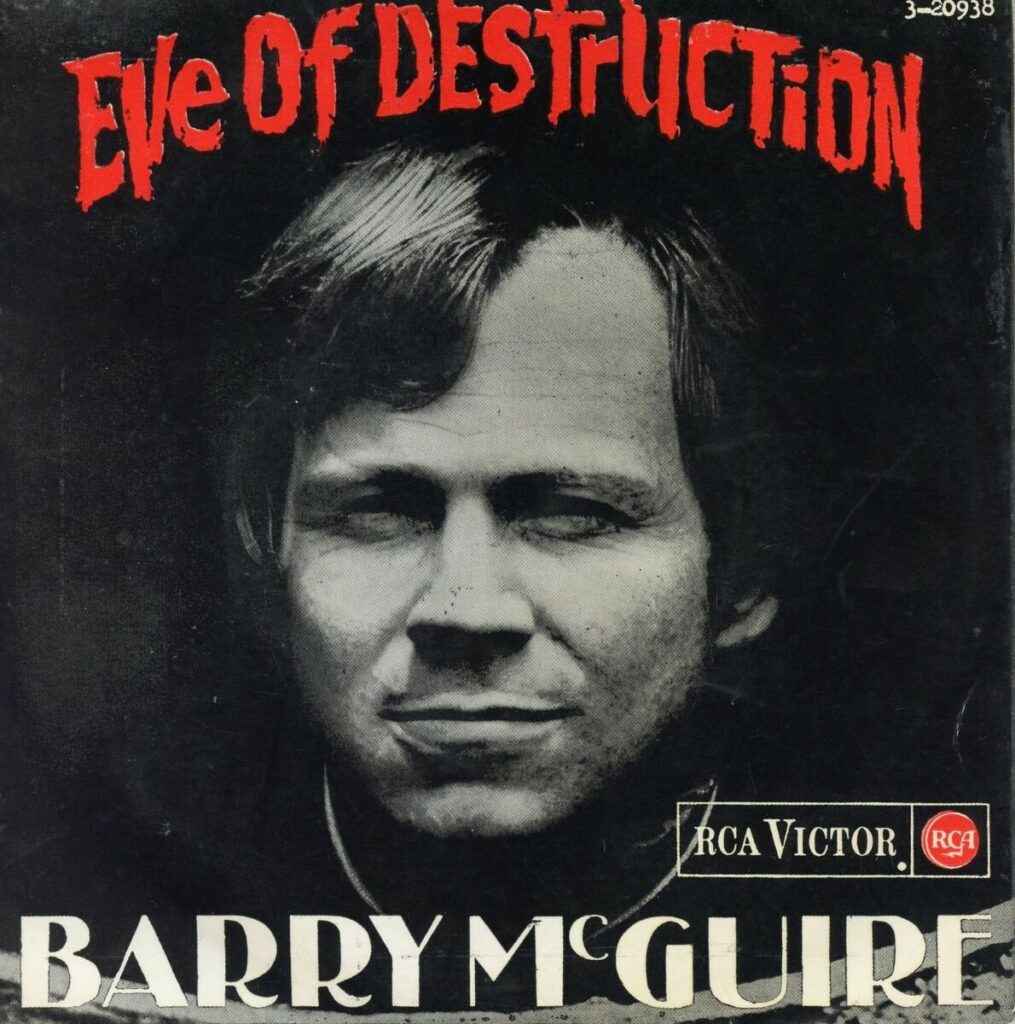

On September 26, 1965, Barry McGuire’s antiwar, topical anthem “Eve of Destruction” hit #1 on both the Billboard and Cash Box Top 100 charts. The sonic wrecking ball had one of the most seismic runs to the top of the charts in music history, but, more importantly, was the first real topical song to be released as a pop single, let alone hit #1, and gave a thumb to the eye of the unsuspecting establishment. It ran the gamut of hot-button issues, from the informal war in Vietnam, the growing Civil Rights Movement, the military draft and the overall political and social frustration being felt by many young Americans. The song stayed at the top position for only one week but it ignited a national conversation and invoked the ire of many a music industry executive. Topical and “anti-American” songs were supposed to be relegated to dingy folk clubs in Greenwich Village and on scratchy old 78s by outdated artists like Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger, not on a pop single with a beat. It came from out of the sky and hit the American veneer like red paint splatter on an original Norman Rockwell painting.

L.A. 1965

If you were tuning into your local Top 40 station in September 1965, you were fortunate enough to hear in real time one of the richest and most musically fertile periods in pop music history. We were a year-and-a-half into the British Invasion and nearly six months into folk-rock, its American response. Radios and record players were littered with new artists like the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Byrds and the Lovin’ Spoonful. Motown had further lifted black music out of the far ends of the radio dial and fervently into the mainstream where it would stay forever. The sounds coming out of car stereos and transistor radios were fresh and magical. And speaking of radio, that too had become a fine-tuned machine thanks in part to programming pioneers Bill Drake and Gene Chenault’s West Coast “Boss Radio” and Rick Sklar’s East Coast Top 40 formats that moved radio along like mass transit with strong personalities, minimal dialogue, catchy jingles and plenty of rock and roll. The money rolled in by the truckload and a booming industry was born. A streamlined system was in place, and everyone was on board, from the record companies to the promotors to the program managers to the jocks. Nothing could get past them…right? Not so fast, my friend.

In Los Angeles, KFWB and KRLA dominated the Top 40 scene for several years, but a new challenger emerged when the perennially poor performer KHJ became Bill Drake’s first major market Boss Radio station. The competition became fierce, and each looked for an edge to get a leg up on their competitors and the biggest key to that was breaking the next big hit. Around town, there were plenty of providers. The rise of rock and roll gave way to its corporatization, and, in its very short life, Los Angeles became its recording capital. Capitol Records and Warner Bros. were both headquartered there, and all the other major labels had significant presences. Independent record labels were popping up all over the place and even though A&M, Liberty and Imperial provided the stiffest competition, it was tiny little Dunhill Records in Beverly Hills that turned this flawless, sophisticated system on its ear in late summer 1965.

A New Challenger

Dunhill started out as the production arm of Trousdale Publishing, which was formed by business partners Pierre Cossette, Bobby Roberts and Lou Adler in 1964, and they immediately hit paydirt producing hit records by Johnny Rivers. Cossette was a TV executive with no real musical acumen. Roberts was a talent agent who made his way into the music business as part of the Dunhill Trio, a dance team who broke into the business 20 years earlier touring with Danny Kaye. They went by several different names and were featured on just about every early television variety show and MGM movie musical, but the word “Dunhill” was always in there. They took it from the high-end manufacturing company of the same name that specialized in sterling silver, which gave them an air of class, and Roberts recycled it for his new musical venture. Lou Adler was the partner tasked with steering this ship. It made perfect sense. He’d had the most practical record industry experience, having entered it 10 years earlier with friend Herb Alpert and turned a Hollywood High duo, Jan & Dean, into a Top 40 stalwart. He also was masterful at forging relationships and brought Don Kirshner and his hitmaking NYC-based Aldon Music songwriting teams to West Coast artists and A&R reps.

Adler was the most hands-on and ran Dunhill’s day-to-day, from managing the staff to signing the talent to producing the records and handling the distribution and sales. He got the latter taken off his plate when Bobby Roberts’ brother-in-law, veteran music promoter Jay Lasker was brought in as a partner. Lasker was cutthroat and made his bones in the East Coast rock and roll scene of the 1950s, starting with Decca and Kapp Records before making his way to Chicago and overseeing Vee-Jay’s distribution. Both cities’ music scenes had a seedy underside rife with mob connections and Lasker managed to swim with the sharks, so Adler and Roberts knew what they were getting with him. For Adler, the presence of Lasker allowed him to focus more on the music and, in this new, competitive musical climate, he set out to load his roster with hitmakers. Phil Sloan and Steve Barri, two Dunhill Productions songwriters, were brought in to write hits and produce the records. Veteran music executive and long-time Barbra Streisand producer Jay Landers, the son of literary agent Hal Landers whose office was just down the hall, remembers the Dunhill crew and artists who came in and out of that office on South Beverly Drive.

“I was nine years old, but I would go every single day to my father’s office just to hang around these crazy people,” he told me.

It’s no wonder that things started out kind of shaky. One of the first additions was Adler’s bride of less than a year, 20-year-old actress Shelley Fabares, who topped the charts in 1962 with “Johnny Angel,” but only had one Top 40 follow-up. Her version of “My Prayer” was the label’s third single. The rest of his roster was a veritable who’s who of unknowns, including Willie & the Wheels, teenage Canadian star Terry Black, Ritchie Weems & the Continental Five and the Ginger-Snaps. And most were one-and-done. Fortune smiled upon Adler in early summer 1965 during a trip to Ciro’s le Disc, a hip L.A. strip nightclub that had been hosting the hottest American group, the Byrds, since their launch in March. Each night was a party and Ciro’s served as a precursor of the L.A. mondo hippie-go-go combination that would dominate the culture in two short years. Leading a conga line that particular night was a blonde-haired, athletic young man with a Renaissance haircut named Barry McGuire who looked like a poetic roustabout in the spirit of Neal Cassady. Adler recognized him right away as a former New Christy Minstrel and the writer and singer of their first hit, “Green, Green.” He followed the industry closely and knew that Barry had recently left the processed folk group. He invited him to sit at his table and after some small talk, Adler told him to come on down to the office to listen to do some demos and maybe join the label. He did just that.

Adler teamed him up with house producer and staff writer Phil Sloan, a talented and pugnacious 19-year-old singer/songwriter with a Bob Dylan obsession. He dressed like him, sang like him and aspired to be like him, but was writing minor pop hits like “Summer Means Fun” for the Fantastic Baggys and Jan & Dean’s “I Found a Girl.” Jay Landers remembers the inscrutable singer/songwriter well.

“Phil was an interesting guy because, even though he had made his mark as a kind of a West Coast version of the Brill Building, in his heart of hearts, he really wanted to be a Dylan-esque poet,” he said.

He was nearly as prolific as his hero, and he inundated Barry with his original songs. The folk refugee was skeptical and rejected nearly everything he heard except for one called “What Exactly’s the Matter with Me.” Barry and Adler came to terms and Phil set up a session where they’d attempt to bang out three songs in a three-hour period and Phil brought two other songs that Barry was warm on, including one called “Eve of Destruction.”

Divine Inspiration All Over The Place

Composed by Phil a year earlier, following the Gulf of Tonkin incident, which led to the U.S. military’s involvement in Vietnam, the song profoundly expressed much of the anxiety, anger and frustration being felt by so many young Americans in the wake of the JFK assassination. Phil, who later recorded under the name “P.F. Sloan,” told anyone who listened told him that the song came to him through a “spiritual inner locution,” or, in other words, from God. One person who wasn’t a believer was Lou Adler. After Phil played it for him, he was unmoved, telling him the song was unrecordable. It wasn’t that Lou took the song personally. It was simply that, 1964, nobody in his right mind would record it and anyone who released it would be even crazier. It was divisive and there was an unwritten rule within the pop industry not to release topical songs.

But the air was changing in western culture by mid-1965. The Vietnam War was escalating and unrest among U.S. was tracking right alongside of it, especially on university campuses. Folk artists were more open to songs with this kind of indictment on the establishment and that’s why Barry gave a thumbs-sideways to the song. Surprisingly, Adler gave permission to record it as a possible b-side or album filler so Phil brought the music along to the Thursday, July 15th session with the hopes that maybe they could get a take or two in and a guide vocal for Barry to take home and practice. With time winding down in the session, that’s indeed all they were able to do. The small group of session musicians on hand, including Phil on acoustic guitar, Steve Barri on percussion, Hal Blaine on drums, Larry Knechtel on bass and Tommy Tedesco on electric guitar, ran through the sheet music a couple of times and had time enough to do one vocal run-through with Barry. He grabbed lyrics, handwritten by Phil on a piece of paper, which had been sitting on a table in the control and was now stained with fried chicken grease. He let loose, singing it in a low growl that gradually built and made the blistering lyrics standout. It had a profound effect on the song, capturing perfectly Phil’s original sentiment of frustration.

Perhaps the biggest mistake that turned into gold came after the part in the song where Phil rhymes “coagulating” with “contemplating.” Because of the grease smudges, Barry lost his place and his frantic search on the paper resulted in a quick “uhhh-ahhh-I-can’t twist the truth…” that accidentally captured the angst felt by someone going through this existential meltdown in private and belting it out from his heart. But, for the time being, nobody really thought much about it. When they were done, the session wrapped up and all the musicians went home. Steve Barri made a dub for Barry and put the master in his office. When he came in on Monday morning around 9:00 am, he gave it another listen. Jay Lasker popped in his office, asked for the tape and took it to his office so he could listen to it again and, over the course of the next three hours, history was made.

“I hear screaming and yelling going on and pounding on the walls in Lasker’s office, and I’m called in,” Steve Barri said in the 2008 “Wrecking Crew” documentary.

Pressing his young producer, Adler asked him what he did with the tape of “Eve of Destruction.” Steve told him that the only tape he had he gave to Jay Lasker.

“There has to be another one,” Adler replied. “Because I just heard it on the radio driving in this morning!”

Somehow a copy of “Eve of Destruction” made its way six miles northeast to KFWB disk jockey Wink Martindale who put it into the rotation of his morning drive show. It quickly became his celebrated “Pick Hit of the Week,” and while there was a sense of excitement emanating from the KFWB studios at the foot of the Hollywood Hills for breaking a new hit, over at Dunhill, there was anger and frustration among the partners. First, how could a song of this nature get recorded and, more importantly, make its way to a popular Top 40 station in a major market? Adler had no choice but to take responsibility for the initial one. He made his feelings known to Phil months earlier when he played it for him but allowed Barry to record it at his debut session. Because of the controversial lyrics, his ingratiation to his new artist came back to bite him.

Of more concern to Adler was that a raw mix of the song was being played. Since beginning as a producer at Keen Records back in the late-1950s, quality sound was paramount, and this new record would have his name on it. The problem was that the song was hot and taking off, so how do you fix what isn’t broken? KFWB’s phone lines were exploding for requests to play it again and teenagers were swarming record shops looking for the single, but none existed. Adler’s pleas to KFWB’s vice president and program director Jim Hawthorne to pull the record until they could provide a suitable mix were denied. Instead, a compromise was reached. They’d continue playing the recording they had but would replace it with whatever mix Dunhill gave them as long as it didn’t differentiate too much from what they had. In a very short period, Adler overdubbed soft background singers that sounded like a distant heavenly choir and a harmonica between verses. Fortunately, time prevented him from re-recording Barry’s impassioned, original vocal and the switch was made. Immediately, promo copies were pressed for radio stations and stock copies hit record stores by mid-August. It hit #1 in both Billboard and Cash Box on September 26th and stayed there for one week. It should’ve been a triumph, and it was to a great extent, but it was also a curse.

“Eve of Destruction” brought the youth voice over the Vietnam War and segregation into the public square and laid it at the feet of the Silent Generation. With its rapid rise to the top of the charts, it opened up a national conversation seemingly overnight.

The song brought Adler and his partners unwanted attention from conservative groups and record industry publications Billboard, Cash Box and Record World lost advertisers for merely charting the record. Hundreds of record stations across the country refused to play it, even though it was the #1 hit in the country. A makeshift studio band who called themselves the Spokesmen released a response song with a copycat melody called “The Dawn of Correction” on August 28th and CBS newsman Mike Wallace dedicated an entire episode of his radio show “Mike Wallace at Large” to analyze both songs and tackle the subject of foreign policy through song. Big market radio programmers were doubly pissed because not only did they have to endure angry phone calls from listeners’ parents, but “Eve of Destruction” reached the top spot without payola by committing the cardinal sin by being a topical song with a melody. Inside the Dunhill offices, some of Adler’s business partners, a couple of whom were World War II vets, were equally perturbed by the song although they were happy with its financial returns. The song’s writer, Phil Sloan, felt completely singled out by Adler and Lasker and believes it held him back as an artist. Even though he would go on to co-write many hits for Trousdale Publishing, including “Secret Agent Man,” “A Must to Avoid” and “You Baby,” he still felt detested by his bosses, which most likely stemmed from his own paranoia.

But, if Adler was conflicted by the song, he didn’t let it show as he’d often send nine-year-old Jay Landers next door to Alpha Beta Grocery Store to purchase the latest copy of Billboard so he could track its progress on the charts. He did understand, however, that Barry would have a difficult time duplicating “Eve of Destruction’s” success as he was a marked man in many markets and his follow-up single would most likely be dead on arrival. But, when you’re on roll, fortune tends to smile on you and that’s exactly what happened to Lou Adler a couple weeks after the official release of “Eve of Destruction” when Barry McGuire walked into Western Recorders with John Phillips, his wife Michelle, Denny Doherty and Cass Elliot to audition for him. Their scraggily appearance belied their exquisite harmony, and Adler would find that out when he tried them out in a vacant studio. The idea was for John to write Barry’s follow up single, which was supposed to be John and Michelle’s hippie clarion call, “California Dreamin’,” but their version was too good to hold back. After naming themselves the Mamas & the Papas, Dunhill released it as their debut single in November, which peaked at #4 in the early months of 1966. But a new set of problems emerged with Adler’s new group. John and Michelle’s marriage was rocky, and the Mamas & the Papas came close to breaking up mere weeks after signing to Dunhill when John learned that Michelle and Denny had had an affair. Adler spent a lot of time trying to keep his new hitmakers together and out on tour.

Aftermath

Notable changes started taking place at Dunhill around the same time. Pierre Cossette wanted out. He lost faith in the whole record label thing and, with the Mamas & the Papas seemingly on the verge of breaking up, asked for a buyout. Bobby Roberts, who never liked Cossette, was happy to oblige, getting office neighbor and literary agent Hal Landers to buy him out for $25,000. But Cossette’s panic would be his folly. Like him, all the partners understood that the Mamas & the Papas could blow up at any moment and Landers convinced the others to sell now before they finally break up and destroy Dunhill’s value. From the beginning, ABC-Paramount was their American distributor and, when they saw what was going on at the growing little record company with Barry McGuire and the Mamas & the Papas, they began to salivate and offered the five partners $3 million for the label and Trousdale Publishing. Adler was retained as the producer of the Mamas & the Papas and Lasker was promoted to president.

“They all thought that they had pulled off the deal of the century, selling ABC – a label built around one group that was breaking up,” Jay Landers said.

“Eve of Destuction” turned out to be the goose that laid the golden egg, but things didn’t end as rosy for Barry McGuire as it did for his bosses. He never repeated the success he had with his Dunhill debut. He was indeed a marked man by radio programmers and industry execs. The closest he came to the Top 40 was with his summer 1966 single, “Cloudy Summer Afternoon,” which peaked at #62. He was summarily released by the label a little over a year later, which was a shame because he was an incredible talent. He was a complete product of an incredibly rich and creative musical era in both style and substance and cut some killer stuff during his short time at Dunhill. Check out “Inner Manipulations,” the b-side of his penultimate Dunhill single. It’s all at once psychedelic, folky and a harbinger of what was to come at the end of the decade. He moved back to New York in 1968 and starred in the Broadway hippie musical “Hair” for a season and ended up returning to L.A. to record for Lou Adler’s Ode label, which only resulted in one single and an album with Eric Hord. After a meeting with traveling evangelical Christian preacher Arthur Blessitt in 1970, he became a born-again Christian and spent the rest of the decade and-a-half recording contemporary Christian albums before moving to New Zealand for several years. He eventually made his way back to the States and continued to record, tour and talk about that crazy music scene his was a big part of back in the 1960s.

“Eve of Destruction” remains a go-to protest song whenever war or fighting breaks out or there’s palpable political strife. It spurred the subgenre of protest rock, which empowered many a young artist to express his or her political feelings of the day in song and gave us songs like Country Joe & the Fish’s “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag,” Dion’s “Abraham, Martin & John,” John Lennon’s “Give Peace a Chance” and Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On,” among others. As with bold statements, “Eve of Destruction” was a double-edged sword. It was a message that we needed to hear, as it masterfully points out many hypocrisies present in Western culture, which, quite honestly, weren’t unprecedented and understandably rankled many people over age 30 – you know, the people you’re not supposed to trust when you’re young and ignorant. And who among us who eventually graduated to old age can truthfully say they weren’t part of those hypocrisies at one time or another? And although there are many things we can learn from the song, it has one big problem. It offers no answers, only an accusatory litany of grievances. But the irony of sending 18-year-olds off to war when they couldn’t vote until they were 21 did etch a place for the song in American political history when the 26th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which lowered the voting age to 18, was ratified on July 1, 1971. The genesis can be pointed right back to “Eve of Destruction.” But it also serves as landmark to the political divisiveness that has permeated our culture in its subsequent years. It certainly wasn’t the cause of it all, as the tension had been bubbling under the surface for years. It just released it, for better or worse, and we’re still struggling with loving our next-door neighbor and saying grace, but truth be told, we probably always have. Still, it’s a cool, iconic song that occasionally pops its head out and makes us think about how we treat our fellow man while snapping our fingers and tapping our toes at the same time. In my humble opinion, the biggest unanswered question in this song’s story is, how did KFWB get a copy of the tape?

Another Great article by Mr. Scott Shea. I enjoy everything he writes. The in depth details are refreshing. I always learn something.