By Brian R. Banks

It might surprise that a best-seller of EMI’s Harvest label, dedicated to alternative not mainstream music, was one of the English counterculture’s vanguard (Edgar Broughton Band, Hawkwind, Pink Fairies/Deviants) with songwriter Edgar seeing them as the more melodic of the three. When either a fearsome foursome or triathlon trio, their sound was always full-on sonic attack going further than the required distance taking no prisoners. It extended thought and rocking while never emasculated flower power but anarchic rebels against the establishment’s social and political injustices nearly a decade before Punk.

Their debut was also the label’s first single (Evil/Death Of An Electric Citizen) in 1969 (Europe only) soon followed by a first LP Wasa Wasa including both songs. Rob Broughton (who preferred to use his middle name Edgar) on guitar and vocals (often called a blend of Captain Beefheart meets Howlin’ Wolf, perhaps a smidgeon of Arthur Brown and Van Morrison minus brogue), brother Steve Broughton (1950-2022) on drums, Arthur Grant bass/vocals, plus Victor Unitt (Pretty Things) on rhythm guitar (only the first 4 songs without him), moved from sleepy Warwick to Notting Hill Gate around the corner from Blackhill Enterprises, most of whose roster (Roy Harper, Kevin Ayers, Pink Floyd) signed for Harvest and performed in their famous free concerts in Hyde Park. Edgar Broughton Band also did Glastonbury when it was akin to the historical Fayres with a Pyramid stage before the sharks took over. Blackhill’s Peter Jenner produced their first three albums at Abbey Road, interviewing them in his magazine Blackhill Bullshit.

Their very hip (“Don’t cut your hair you’ll spoil your image”), supportive parents Joyce and Dennis drove the fledgling blues band after gigs to the famed Blue Boar Café for another early version of networking, once having John Mayall crash at their home. John Peel said the senior Broughtons also roadyed and brewed tea backstage, the DJ liking Mrs. Broughton’s roadside soup! Blues were only part of their taste when the genre adorned their name at the outset, though Steve and Arthur were more into Soul. Combined with shared rock tastes, these melded into a distinctive signature sound fused in psychedelia heard on five studio LPs and six singles on Harvest then other labels up to the last 40 years ago.

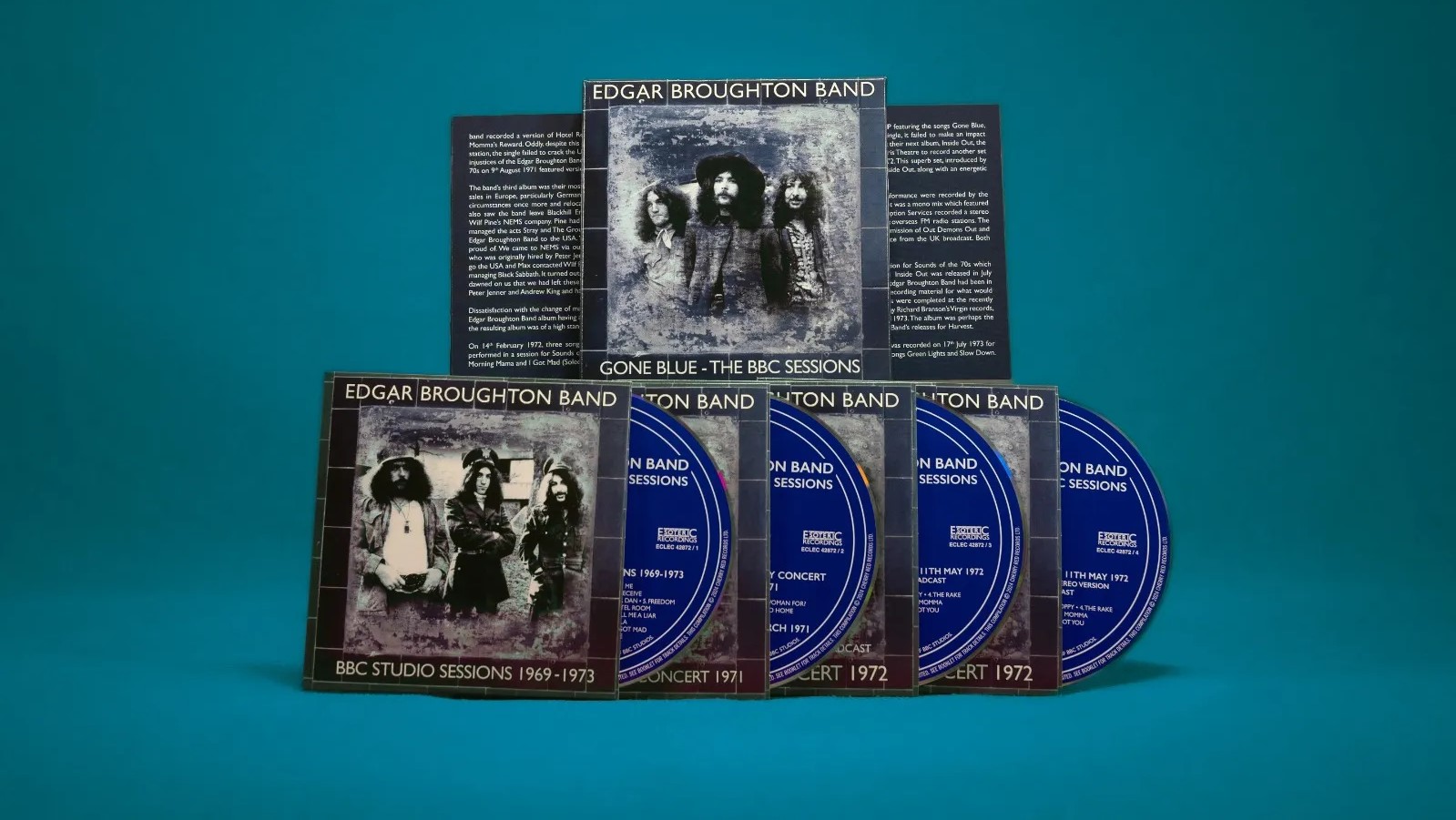

A new box from Cherry Red/Esoteric features tracks from all of their surviving BBC recordings from 1969-73, the Harvest years, mostly John Peel’s shows but also what sounds like Alan Freeman or the World Service that used transcription discs, fortunately because the BBC care as little for their wiped archives as for truth which they whitewash over as we all know. In the press Peel wrote warm comments about the band as rare in the business for keeping to their ethical ideals with socio-political songs and lifestyle. A recent Dutch press release, as a special guest of Focus, called Edgar a “fire and brimstone preacher”!

Coinciding with the month of first LP sessions in January ’69, their radio bow is here with a pair of acid-rockers: a slightly shortened Why Can’t Somebody Love Me plus an unreleased For What You Are About To Receive. At the year’s end they did a gig at Abbey Road studios, unreleased until the CD era except for a single of their Fugs-influenced chant Out Demons Out (here on the third CD’s In Concert) with Momma’s Reward (Keep Those Freaks A Rolling), reaching #39 (33 wrongly in the booklet) for 5 weeks. Probably the first ever mash-up 45 (early sequencing!), it befuddled BBC’s Juke Box Jury hosted by David Jacobs.

A couple of months later Up Yours! (string-arranged by David Bedford) satirised the General Election backed with Officer Dan featured with There’s No Vibration But Wait from the second album, Sing Brother Sing which reached the top 20 fuelled by tabloid press notice. Arrests, fines, witness defending, strike support etched their agit songs and lifestyle. A tabloid’s bigot said the band is popular in Germany so they should stay there and not return to where they’re unwanted. At the Aachen Open Air Festival, Edgar stopped the concert to point out police surveillance, the crowd then went there chanting Out Demons Out. Police left after ten minutes and stopped beating people. Once David Bowie joined them onstage to chant it, resulting in a lifetime ban from the venue (Dome, Brighton). Edgar recently said that EMI didn’t realize that the band were preparing the suits for those Sex Pistols who were truanting up the road.

Unitt returned from the Pretty Things’ Parachute for the Broughton Band’s September 1970 broadcast, the non-album Freedom (longest track on the first disc) and a buzzing version of The House Of Turnabout about places and people from their eponymous LP (also called the meat album due to its Hipgnosis cover) that hit #28 in two weeks of June ’71. Edgar later told Terrascope that the label was honest but mean, they paid small royalties but not advances (just as well as musicians spend years paying them back, like a bank). Another perverse gesture to EMI was the single Apache Dropout, a fusion of the Shadows and Captain Beefheart (an influence on Edgar) which still peaked during 5 weeks at #33, stymied by a postal strike when sales data from record shops weren’t sent. A rollicking cut is here In Concert with its Apache-fled live title Drop Out Boogie.

The LP was soon followed by a non-album double-A single Hotel Room / Call Me A Liar, which should be on every jukebox worth the name. It seems to flag the singer’s feeling about his place in life but can touch everybody: “Old man, young man, tired woman, raise your soul in the centre of life”. It was even home-spun Tony Blackburn’s daily record of the week while at pains to distance himself from their ideology. An Italian website likened it to “a dazed ballad worthy of Syd Barrett” but why not Lennon? Another called it almost “a theme from an imaginary modern western”. It could have been the era’s anthem.

It’s here in another memorable take with the pre-grunge Momma’s Reward (Top Gear July ’71). The album sold well in Europe, especially Germany, and they moved not there but to Devon while leaving Blackhill for NEMS (linked to WWA) who were literally gangsters connected to the infamous Kray Twins. Others who regretted the move included Medicine Head, Stray, Groundhogs and Black Sabbath who took them to court and won. Four songs here were written for fourth album Inside Out (1972) and span two Sounds Of The Seventies airings February-June 1972. Among others are a heavy as a bum rap Call Me A Liar directed at the judge, a hand-clapping warning about pollution and paranoia (Poppy), a plaintive live-fave Chilly Morning Mama (“…just say I live between both sides of the road”), an angry protest at not-guilty prisoners (I Got Mad) and a pair with the most ‘sexy’ Beefhearty lyrics they ever did (The Rake and title track, blues on magic mushrooms that was on a between-album EP).

The last two in July 1973 are from follow-up Oora the next year: the beautiful ballad Green Lights reminds a little of the songwriter’s taste for Pearls Before Swine (“I love Balaklava”), a classic freak folk album of 1968, while Slow Down is premature-by-years Punk fuzzed up with great bass and drum middle breaks. Some here are among their best-ever when all are good, no doubt because radio and live remove weaker songs though they were rare in their repertoire. I don’t agree with carpers about relevance: it is music from the time but (so far) for every time. Is blues only for sharecroppers, Beatles for screaming schoolgirls, Mozart for those in wigs? Music is music of course.

After the 17 track first disc is an early 1971 Paris Theatre show in Lower Regent Street for Sunday’s In Concert, which was wiped but survives from the overseas network. It excludes Poppy but that’s forensically retrieved incredibly from a very rare Top Of The Pops export version! There must have been no support as the concert is almost an hour and among their best. An 11-minute Freedom has extra lyrics than its B-side of Apache Dropout, which is also extended to over 13 minutes with underrated solos and audience response chanting. The Birth from the third album is alongside a 10-minute What Is A Woman For? dreamy mood.

Their last Harvest album Oora, started at Morgan in Willesden and finished at the newly opened Manor Studios near Oxford owned by Branson, was probably the most ambitious. Just prior was an In Concert (May ’72) compered by Andy Dunkley who often DJed at the Roundhouse including the famed Greasy Truckers Party with Hawkwind that I attended, but very amusing intros by Edgar render him almost redundant. Nine songs from the post-debut albums are on CD 3 in the UK mono version (bootlegged on vinyl back in the day but never this full and loud) of which Out Demons Out was excluded for the stereo overseas broadcast (CD4 here) with a different mix balance and run-out times, the last track cuts almost 5 minutes of audience frenzy starting Out Demons Out themselves before the band rejoins for the unaired encore. Both formats really cook showing their visceral live energy as one of the most charged bands ever at their peak.

Side By Side with prescient lyrics and 90s style guitar decades early, with an unlisted Sister Angela (a short epistle to a nun), opens for a swirling, stomping and indeed mesmerizing Call Me A Liar written after a free festival in Redcar where a fight broke out with the police. The studio version was on a famous budget sampler (the Harvest Bag 1971) but here with solos from them all sharp as a King-size Rizla a la Grateful Dead. Poppy is a sing-along about pollution and the plastic people out having a picnic, The Rake is adorned with a bit of acid slide, while a 15 minute It’s Not You is a truly thought-provoking hallucinogenic stomp (“Talk about the prisoner that’s everyone I know / Let’s all pray it isn’t you”). Out Demons Out is a literally thundering tribal exorcism in a voodoo beat that simply is the entire period ethos in a micro bottle or tab, taking you back to where people said hi and peace in the street to each other on a sunny or rainy day. A true rock and holler by a psychedelic powerhouse.

The last album’s failure to chart led to friction between label and management, so they left EMI and Victor Unitt left the band. Bandages (1975), Live Hits Harder (1978), Parlez Vous English (1979) and Superchip (1982) were their last until solo albums supplemented by numerous archive and live collections in recent years. In fact, on the one-time community youth worker’s current solo The Sound Don’t Come is about Mick Farren who died onstage not so long ago. Often charged back then with “civil disorder”, fights including vandalism (Keele University’s audience—namesake of the Ohio college where students were shot by the National Guard—were handed paint by the band which they used on the venue) and free benefit concerts for worthy causes held the torch for the Punk movement a few years later. Graffiti references still can be glimpsed around the country. Painting-like imagery, stories, anthems, slogans, apathy-attacks of advice, love ballads, maybe even prayer are bundled up in a musical incendiary device designed to shatter safety glass and concrete.

This boxset is superbly remastered original BBC tapes and claims 32 unreleased tracks of what was a people’s band sharing the interests and opinions of their audience. Career-spanning recordings (like their live shows) highlight complex issues encompassing that time and still influences today. Edgar Broughton’s view in the excellent booklet that his “little messages…may not have been articulate but were certainly passionate” sidesteps that their relevance is as appropriate today as then, and that is some legacy. There’s no hype here, no ego posturing, only a timeless communique for and from the people embracing their very DNA in legendary music of its own. Without it, (the) time would be poorer. Dare I say, humbly and realistically without exaggeration, that absence of these musicians in your collection is equivalent to a hole in the head or unaware trepanning?

Brian R. Banks