In The Endless Refrain, veteran music journalist David Rowell presents a thought-provoking analysis of the modern music industry, focusing on how the rise of streaming services, the consolidation of digital platforms, and the increasing nostalgia for past music have drastically altered the cultural landscape. Through a blend of memoir, reportage, and cultural criticism, Rowell dissects the forces driving today’s musical homogenisation and the challenges faced by emerging artists in an age where algorithms shape our listening habits.

Was there a specific moment or event that triggered your decision to write The Endless Refrain?

About eight years ago, for the last chapter of my last book, I spent a week shadowing one of my closest friends, Bob Funck, who had managed to line up a string of performances at cafés and bars in the Northeast. You couldn’t quite call it a “tour” because no one knew who Bob was, and no one would be turning up at the venue in question because he was performing there. He’d put out one CD that he financed, but he was also armed with a stash of great—musically, lyrically—original songs. Each night he played to absolutely indifferent handfuls of people—sometimes it was two, 15 or 20 at the most—who sometimes talked louder than he sang. One night at a pub in Portland, Maine, Bob was booked to play three hours, but he didn’t have enough material to fill that time, so he threw in a Tom Petty cover just to extend himself. And as soon he began, everyone in the place suddenly stopped what he or she was doing and began listening so intently. And they were so rapt because here was a song they knew. The relief! It wasn’t even a particularly interesting cover, but what this brief burst of attention showed me was that on one level they had been listening just carefully enough to know that these weren’t familiar songs, so they’d tuned out. As soon as Bob finished the Tom Petty song and went back to his own music, it was like those four minutes had never happened at all.

So there at the bar I wrote for the first time, “Do we even want new music anymore?” And once that question was in my head, I couldn’t shake it. And the reason for that is because I felt like I knew the answer, and I couldn’t get over the shock of that. So the book explores all that and tries to reconcile how we got to this point—while taking measure of what it means for the future of music.

Can you elaborate on how platforms like Spotify have demonetized artist revenue and what that means for the future of music?

The basic foundation of Spotify’s arrangement is: Spotify’s payments to artists are broken down between recording royalties and publishing royalties. That means money goes to whomever holds the rights to the recording or the owner of the recording, which is usually the label or a separate distributor; similarly, money is paid to the songwriter or songwriters of the song or the owner of the composition, typically through some third-party agency such as a music publisher. Based on Spotify’s payment model, artists can reportedly expect to receive between $0.003 to $0.005 per song streamed. And for a great many musicians on Spotify that amounts to extraordinarily little money. A lot of artists have been really vocal about this, but not the artists who get streams in the hundreds of millions, or even billions—like Drake or Bad Bunny or Ariana Grande.

In late 2023, Spotify changed its payment policy, and for lesser-known artists it only got worse. In a lot of ways Spotify is the world of music’s haves and have-nots, and if the have-nots don’t make any money from the world’s largest streaming service, then it becomes that much harder to sustain their musical careers.

You argue that algorithmically driven streaming services lead to homogenization rather than expansion of taste. Could you explain how this process works and its implications?

I do believe that if we let streaming services make all the decisions for us, that can keep us in a place of musical sameness. That can go well beyond to just listening to the same genre all the time, but very often within that genre you can get the same kind of mood, the same tempo, the same kind of vibe. And, you know, we should get more from music than sameness. The algorithm figures out what you like, and Spotify definitely wants to keep you where it finds you, without disruption. It wants to keep you in a trance state and keep the streaming numbers racking up. And no streaming numbers matter more than Spotify’s. It’s all about retention and revenue.

The process is built around a very highly specialized way of tracking—much of which Spotify works hard to keep private—but in general the AI and software analyze the metadata in the track itself, which includes, beyond the basic information of the artist and the producer, say, or the composer, but tags labeling the instruments used on the song, the lyrical content, etc. And once it’s created the dissection of that song you’re listening to, the software finds other songs that closely resemble what you just heard. All of this happens in an exceptionally little amount of time, of course, but the consequences of that can be very long-lasting if you’re not careful. The more we keep gravitating toward only one kind of music, one kind of song, one kind of artist, the more musical conformity we get—and the harder it becomes to find something at all different.

Why do you think there’s such a strong tendency to look to the past in popular music? How does this affect the production and reception of new music?

I think there’s no other art form with which we create such an intense bond, emotionally speaking, than music. And this has its most intense peak when we’re young, when we’re still trying to figure out who we are and the world around us. The songs we’re listening to when we’re young give us a sense of not being alone during that often-confusing period, and like good friends, they can really comfort us when everything feels so dramatic—grades, relationship stuff, how we perform on sports teams, what we’re planning for life after high school.

Years later we realize that those same songs have become vessels for those memories. For a lot of people it feels good to slip back into those memories, especially when life has become much complicated in new ways—family issues, career issues, the complexities of adult life. And we just don’t make the same emotional connection with new songs as we get older. We can enjoy new music, but it tends to ultimately mean less to us. It stops feeling important. And so we inevitably seek it out less. This isn’t true for everyone, of course, but in the years of my reporting I found that it to be pretty true for the majority of folks.

What are your thoughts on the rise of tribute acts and dead/retired artists touring/playing shows via hologram? Do you see this as a symptom of the issues you discuss, or a separate phenomenon?

When it comes to live music it’s all about what’s most important to you. The hologram show is a really different experience than the tribute act, but it’s also tapping into the same deep hold nostalgia has on us. The consideration there can come down to which you think is better: seeing someone in a Roy Orbison wig who sounds a lot like Roy Orbison, or a digital creation of Roy Orbison that has Roy Orbison’s actual voice?

Tribute acts are an easier idea for a lot of people than a hologram show. The tickets aren’t that expensive, parking is no hassle. Plus, there are so many tribute acts around these days that it can be harder to find a Pizza Hut than a band that dresses and sounds like Queen or the Beatles.

If you want to see the Eagles because you love the Eagles, does it matter to you that there are more musicians on stage who didn’t play on those great Eagles albums than didn’t? In the book I write about a Journey tribute band called Never Stop Believin’, and they have exactly one less original member than the current lineup of Journey. Do you care who’s on bass, who’s on drums? Did that ever matter to you? These are the kinds of issues some people sort through. The Eagles’ shows are sold out through this year, so I think one thing that says is, people want to say they saw the Eagles for the first time or the last time while they are still officially the Eagles. When you’re taking that selfie at the show—is it important to tell your friends you’re seeing the Eagles, or it is just as cool to say you’re seeing a band called Tequila Sunrise that plays Eagles music?

I tend to be hardcore about certain things in music, and that just comes out of the particular way I love it and the acts that have meant the most to me. But I also discovered during the reporting of the book that there is a way to overthink all of this, sometimes, too. To me, music is everything, but there is also room to be a little more forgiving and just have a good time.

Given the current trends, what do you believe the future holds for the music industry? Is there a path forward that can revitalize the cultural landscape?

I can’t underscore enough that I think there’s a lot of new great music being created all the time. The future of music should be entirely limitless, but I don’t actually feel like that’s true right now because we have convinced ourselves that the best music we can hear is the music that was created a long time ago. And even if that is true, there are still so many great discoveries you can make in new music.

One thing that I think is really important is for artists to feel bolder about playing new music in concert vs. the ubiquitous one song off the new album and then delivering the same old hits. I went to see a band recently who has been around for decades, and they had a new album the singer told the crowd that they were really proud of. But she was so sheepish in announcing that they planned to play a few songs from it. She was practically apologizing about the situation. It was all I could do to not stand up and say, “Play your new music!” I think musicians and artists have to not just always give us what they think we want. Yes, fans tend to just want the hits, but to artists I say, if you really believe in your new music, then play it and see what happens.

I do worry that this deep nostalgia stronghold we’re currently in, as it relates to new music, is going to be hard to reverse as music catalogs keep getting sold for tens or hundreds of millions, and we’re going to keep hearing that same music in all kinds of ways—ways we haven’t even encountered yet. Whatever the path forward might be, it doesn’t have to about ignoring all the great music from the past. But it does have to really be about at least trying to embrace what’s happening now, in this moment.

Further information

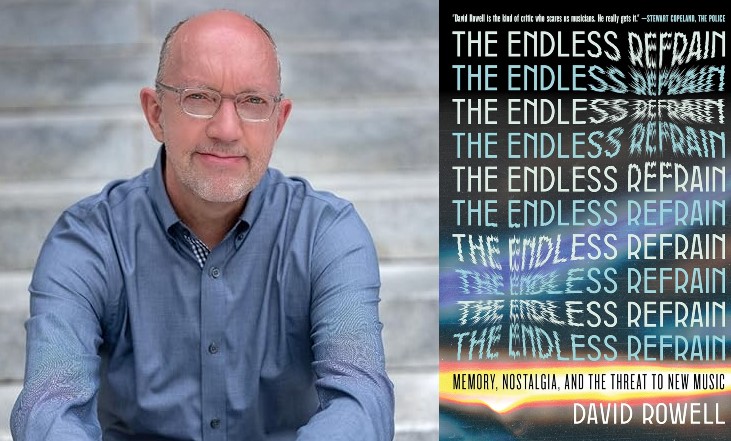

The Endless Refrain: Memory, Nostalgia, and the Threat to New Music by David Rowell

The Rolling Stones saw this coming very early

And made the hugely lucrative decision to turn themselves into the best Rolling Stones tribute band

Mick Jagger the 81 year old ‘Street Fighting Man’

The reflection on how streaming services and nostalgia-driven trends dominate the music industry is both compelling and thought-provoking. It highlights the tension between commercialization and creativity, suggesting that true innovation in music may be slipping through the cracks as listeners and platforms cling to the familiar. A stark, yet relevant commentary on today’s musical landscape.