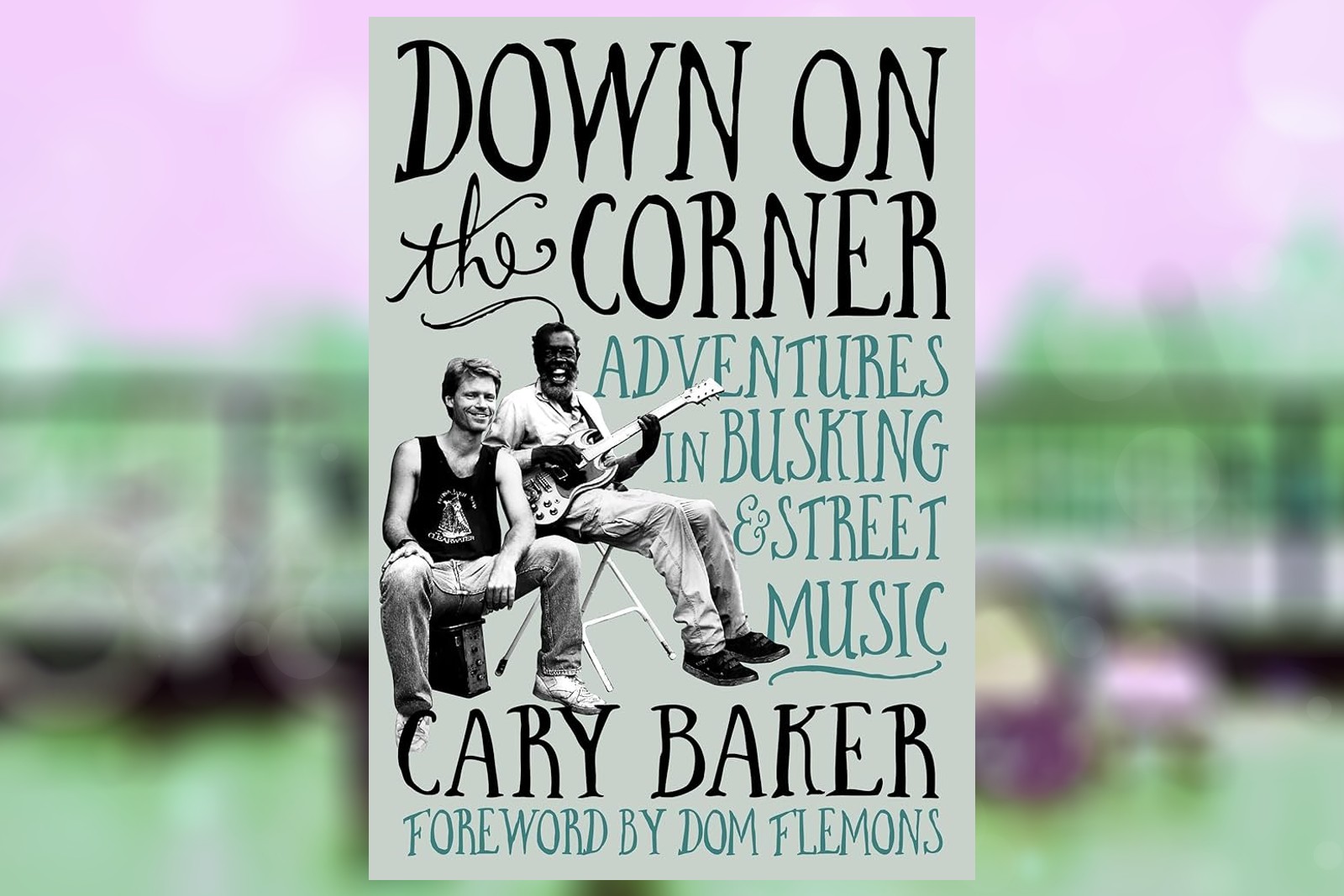

In Down On The Corner: Adventures In Busking & Street Music, music industry veteran Cary Baker uncovers the untold stories of street musicians who shaped genres from blues to rock, folk to jazz. Through interviews with Billy Bragg, Lucinda Williams, and The Violent Femmes, as well as lesser-known but equally captivating performers, Baker explores the evolution of street music from its roots in ancient times to today’s digital era. His personal journey with busking began on Chicago’s Maxwell Street, sparking a lifelong fascination with the spontaneity, resilience, and raw artistry that define this often-overlooked subculture. In this interview with Jason Barnard, Baker offers a compelling glimpse into the lives of musicians who have turned the streets into their stage.

You trace the origins of busking back to ancient Greece and Rome. How do you think busking has evolved in terms of its social and cultural roles since then?

From what I’ve read, music was only mere portion of what the earliest buskers brought to the community. They were carriers of news long before newspapers. American founding father/inventor/philosopher Benjamin Franklin wasn’t really musician by definition, but his town-square orations combined a role as a news tribunal with that of poet and even, according to his biography alludes to sailor songs, adding: “they were wretched stuff, in the grub-street ballad style.” Hard to know exactly what he meant. With the advent of newspapers and electronic media, buskers eventually became able to stick to the music – leaving the news to journalists.

Your first exposure to busking was through Blind Arvella Gray in Chicago. What struck you most about that moment, and how did it shape your lifelong connection to street music?

I was 16 years old, growing up in Chicago, when my father told me he wanted to take me to the city’s Maxwell Street Market where his Eastern European immigrant parents used to take him shopping in the early ‘40s. By the late ‘40s and into the ‘50s and beyond, Maxwell Street Market had turned to a predominantly Black clientele, and it wasn’t uncommon in around 1948 to see later legends like Muddy Waters, Little Walter and even Chuck Berry playing on the street. So when I got my first glimpse of the area in 1971 or so, I was a 16-year-old somewhat sheltered suburban teenager – who did like blues – so the sight and sound of Blind Arvella Gray and his slide resonator guitar blew my mind. We walked around the Market some more and saw other artists that same day: Maxwell Street Jimmy Davis, who had one Elektra LP; Jim Brewer; Little Pat Rushing; and Granny Littricebey (Granny was Arvella’s sister, it turned out). I felt the urge to communicate my “discovery,” and sent an on-spec article to the then-neophytic Chicago Reader, which ran the story. In a sense that launched my writing career at age 16 – and I’m reclaiming that career at age 68! Arvella and I became friends of a sort, although we’d stepped out of touch prior to his 1980 passing. I never looked at street singers the same way. And I began to see others: Several buskers out in New Orleans’ Jackson Square over my many visit to the Crescent City; The Violent Femmes in Milwaukee in 1983, Ted Hawkins and Harry Perry on Venice Boardwalk when I moved to Los Angeles in 1984; and several buskers during South by Southwest (SXSW) like Mary Lou Lord – who played outside because she couldn’t get an official indoor SXSW showcase.

Why do you think busking has such a strong connection with disabled musicians, such as Blind Lemon Jefferson and Reverend Gary Davis?

Disabled musicians – most of whom had the disability of blindness in common – played blues and played on the streets…and all over the country as well. You had Blind Lemon Jefferson in Dallas; Rev. Gary Davis in Durham, N.C. and later New York; Pearly Brown in Macon, Ga,; Blind Arvella Gray and one of his blind peers, Jim Brewer, of course in Chicago; and later Cortelia Clark in Nashville; and Oliver Smith in Midtown Manhattan. Alec Jefferson, brother of Blind Lemon Jefferson, recalled how rough it could be: “Men were hustling women and selling bootleg, and Lemon was singing for them all night.”

And those are the ones we’ve heard of – imagine those who played on the streets and weren’t “discovered” and asked to make records. Why, you ask, do disabled artists tend to busk? Well, there was likely a thread of resigned begging among impoverished disabled individuals. The artists I named here developed a skill, a trade. Of the aforementioned, I only knew Arvella Gray personally. But I’m happy to say that busking three days a week (Maxwell Street, Jazz Record Mart and the Englewood El train stop on Chicago’s South Side, he lived comfortably in a walk-up flat on Chicago’s South Side. It wasn’t lavish but it was comfortable enough. I visited a couple of times, when interviewing him, and when picking him up for the recording session we did with him.

You mention the informality and spontaneity of busking. How do you think these aspects contribute to the unique appeal of street music compared to more formal performances?

Several artists I interviewed, ranging from the Violent Femmes to Mary Lou Lord to Eilen Jewell ro Old Crow Medicine Show and Poi Dog Pondering talked about keeping the busker spirit alive, even as their careers have advanced to higher levels. One of the most intriguing stories I heard was from the artist today known as Fantastic Negrito. But as Xavier Amin Dphrepaulezz – his stage name simply Xavier – he’d been signed to Interscope Records. That didn’t mean his career arc had the trajectory of Interscope label-mates like Snoop Dogg, Dr. Dre or Eminem. His album failed by Interscope standards, and he left the label. Only after the Interscope did Xavier find his inner Fantastic Negrito by playing on the streets and, as he puts it, “not caring.” The street performances were for his sense of purpose and staying well-practiced, but they took on their own life. Today he has a Grammy Award as Fantastic Negrito.

Some of the musicians you cover, like Billy Bragg and Lucinda Williams, went on to achieve mainstream success. In what ways do you think their busking roots shaped their careers?

In my book, Billy Bragg probably put it best: “The artists that I admire are the ones who are tuned into what’s happening around them, and are able to adapt to that, respond to it, and make it part of the show.” That’s busking to me. That’s why I think of as busking. The skills that I learned on the street still inform how I perform. In certain circumstances, I fall back on that experience, I’m not fazed by it. Because I have something to fall back on and say, yeah, I’ve been in this situation before, right? Then there was only, you know, maybe a dozen people every five minutes. Now [playing festivals] there’s 12,000 people but it’s still the same mindset I need is not to be intimidated, suss them out, see how they react, and if they’re reacting positively, they can probably hear me they’re probably enjoying it. Trust your sound person and just do a gig – and come on stage and everyone’s happy. When everyone’s smiling, I’m good. That’s money in the hat for me…I like a bit of that spontaneity. I like a bit of devilment, really.”

You speak about the unwritten rules of busking. Could you share any particularly memorable moments between buskers navigating these unspoken codes?

In New Orleans, Ethan Ellestad, executive director of the musician advocacy group MaCCNO, publishes a “New Orleans Street Performers Code of Etiquette” for buskers, including the following guidelines, among others: “You have an obligation to preserve the heritage of New Orleans music and culture”; “Do not block doorways of any businesses or residence and audience should do the same”; “No one ‘owns’ a spot, it is however acceptable to ask another performer how long they plan on staying at a spot, without being demanding or rude.”; “Pedestrian traffic should not be obstructed in any way”; “Welcome new performers and teach them the rules.”

While some buskers like New Orleans’ David & Roselyn spoke of waking up in the wee hours to claim the best and highest-trafficked “squats” at 3 a.m. prior to reserve for when dawn breaks and people are out on the sidewalks at 8 a.m., there’s an unwritten code that certain corners or other spots along the street or park belong to performers who have shown up there for months and years.

The role of women in busking is an interesting one, with figures like Mary Lou Lord making their mark. How do you think the experience of female buskers compares to that of their male counterparts?

Oddly, I didn’t sense much differentiation between male and female buskers. I looked back at the book just now to make certain I wasn’t missing something major. Mary Lou Lord describes one scenario: “This dude came down, and he had one arm, right? And he was huffing, like he had this big black ring around his mouth. And I swear to God, he had a dog with three legs—this little tripod dog—and he’s got one arm. So he sits down next to me, and I’m like, Oh, jeez, and we looked like a pathetic little gypsy family. Eventually they fell asleep—the dog and the man—and I’m still playing. And probably about an hour or two later, he wakes up and he stands up and the dog stands up and shakes, and he stretches his one arm out and turns toward me and I’m like, What the fuck is he doing? He’s standing right in front of me. I’m like, What are you doing? He whipped out his dick and he pissed all over the fucking money. And I’m like, What the fuck?” One can only conjecture whether or not this would happen to a male busker.

Overall I sensed an air of acceptance for female buskers. Jazz singer Madeleine Peyroux spoke of living in France with her bohemian mother and teaming up as a teenager with Danny Fitzgerald, who’d had history with Bob Dylan and was one of the few buskers to own a Mercedes Benz and boat. He took teenage Madeleine underwing with no reports of taking advantage. While young, she was considered part of the band, and that seemed to be that.

You’ve spoken with many buskers about the impact of social media today. Do you think platforms like YouTube and Instagram have fundamentally changed what it means to be a street performer?

Harmonica player Adam Gussow, who teamed several decades ago with Harlem blues singer Sterling “Satan” Magee (and is now an author and English lit professor at University of Mississippi), talks about technological advances: “If you have a cash app, it’s all legit. Every cent you make, it’s all on the table, right? Somebody out there is collecting data on how much money you’re getting through that cash app. Five dollars now would be more like the dollar people used to give. A dollar now doesn’t seem like very much, although it did add up back in the day. I would be very interested to know—from the standpoint of longtime buskers who’s been doing this for a while—how the cashless economy has gotten them adapting. Here’s the other thing. If you have a cash app, it’s all legit. Every cent you make, it’s all on the table, right? Somebody out there is collecting data on how much money you’re getting through that cash app. Five dollars now would be more like the dollar people used to give. A dollar now doesn’t seem like very much, although it did add up back in the day. I would be very interested to know—from the standpoint of longtime buskers who’s been doing this for a while—how the cashless economy has gotten them adapting.”

Mary Lou Lord has a daughter, Annabelle Lord-Patey, who has busked. Lord proud of spawning a second generation of street singers. She says she showed her daughter the ropes I told her, “Work smarter, not harder.” In fact, in certain ways the daughter has become mentor to the mother. Lord said: “The tradition continues… I’m glad she knows this skill because (a) Annabelle will always have a friend and (b) she’ll always have a job. Be your own boss and play when you want and put in the time as much time as you want. It’s a great, great thing to have that skill. She even told me, ‘Mom, you gotta get a Venmo and a QR Code!’”

Which isn’t to speak of the ability to alert fans to street shows with social media. A simple post on Facebook of Instagram draws fans. I frequently see New England busker Ilana Katz Katz (that’s right, Katz Katz) publicizing street appearances on Facebook. She’s one I wish I’d gotten into the book. (A Volume 2 is not out of the question!)

From your research, is there a specific busker you came across who you felt deserved more recognition for their contributions to music?

Admittedly everyone I featured in the book – whether I spoke with them, or, especially if deceased, I did not – attained some measure of success. But every town has buskers who will never receive their lucky break – like a Geffen A&R man who’d also signed Beck to the label chancing upon Venice Boardwalk busker Ted Hawkins in the ‘90s.

For every Hawkins, there are street musicians who subsist spartanly from guitar case spare change yield to guitar case spare change yield. Eilen Jewell spoke of success meaning being able to afford an avocado to go with her beans and rice. Poi Dog Pondering’s Frank Orrall’s eyes glistened as he described the day his band could afford ingredients for pasta and sauce. Not everyone will become a Glen Hansard, a Lucinda Williams, or a Tracy Chapman. But hopefully they can put a comfortable roof over their head like Blind Arvella Gray. And one and a million, like Cortelia Clark, might win a Grammy.

I hope the book will bring some awareness and support of buskers everywhere. And to stop and listen for a moment – after all, the next busker they hear may become as famous as Jewel or Lucinda Williams.

Further information

Down on the Corner: Adventures in Busking and Street Music is available for pre-order at Amazon