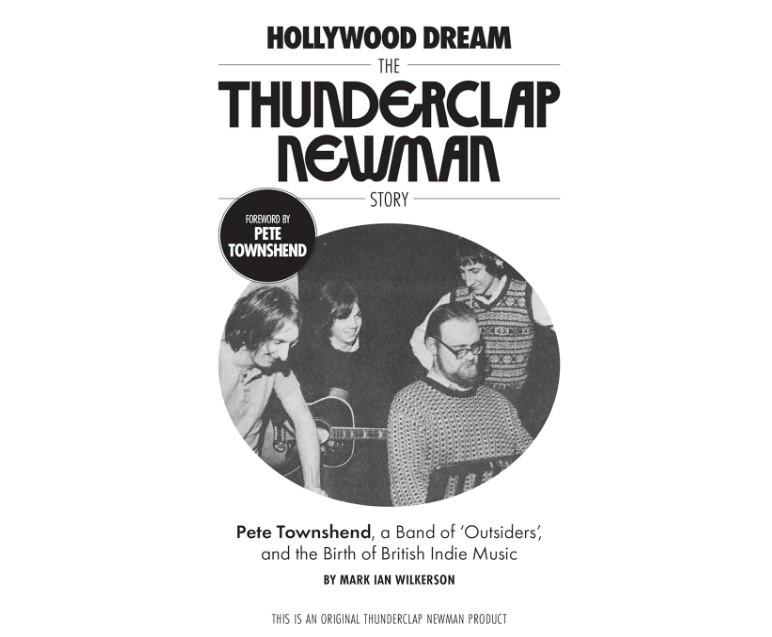

Mark Wilkerson, author of ‘Hollywood Dream: The Thunderclap Newman Story’, shares the journey behind the creation of the book. It examines one of the most surprising collaborations in the history of popular music, featuring four very different personalities: Pete Townshend, the main songwriter and guitarist for The Who; his close friend and driver, John ‘Speedy’ Keen, who was also a singer, songwriter, and drummer; a 15-year-old guitar prodigy named Jimmy McCulloch; and an enigmatic telephone engineer with a talent for improvisational jazz piano, Andy ‘Thunderclap’ Newman.

My first book, ‘Who Are You: The life of Pete Townshend’, was published by Omnibus Press in 2008. Clearly, I didn’t want to stop interviewing people who knew Pete, and carried on doing just that. In 2009, I interviewed Roger Ruskin Spear, who had attended art school with Townshend, and Arthur Brown, who Townshend had recruited and signed to the Who’s record label, Track Records. Spear recalled his first impression of Townshend: “I was aware of this bloke with a huge nose and a spotty bow tie and a yellow shirt and a blue jacket, and he’d be sort of grooving, and I thought, ‘Well there’s a guy who’s obviously enjoying being in art school!’” Brown, meanwhile, recalled Townshend’s attempts to woo him to Track: “He invited me to Soho and took me for a drive in the first car I’d ever gone in that had electric windows. It was big and American, and pretty impressive.”

That summer, I interviewed Andy ‘Thunderclap’ Newman, who wowed me with his encyclopedic knowledge of all manner of things, particularly multi-track recording and American jazz of the 1920s and ‘30s. I wowed him, too, when I relayed a couple of accounts of how highly Pete Townshend regarded him, starting in 1963 when Townshend saw Newman perform for the very first time. Townshend was reportedly “obsessed” with Newman for a time after witnessing the pianist’s odd interpretations of various tunes on piano and kazoo. The normally talkative Newman was temporarily silent, amazed that he hadn’t known any of this over the intervening five decades. “Well, well, well,” he finally said. “You’ve taken my breath away there.”

It was great stuff, but in truth I had nothing to actually do with these interviews; no articles or book to write. I told myself that they were for an update my Townshend biography – a 600+ page book that had just been published the previous year. Here we are, sixteen years later, and that update still hasn’t happened.

Soon, I had other books to write. Eddie Vedder (who had written the foreword to my Townshend biography) asked me to help write Pearl Jam’s 20th anniversary retrospective ‘PJ20’. A few years after that, I got to know a paralyzed American soldier and peace activist, Tomas Young, and I wrote a book about him. These were surreal, life-changing experiences.

Still, that interview with Andy Newman stayed with me. I had never forgotten sitting at my kitchen table that July day in 2009 and speaking on the phone with the enigmatic pianist, our conversation veering off in all manner of directions: Bix Beiderbecke, Muhammad Ali, rugby, cricket… Nor had I forgotten the letter he sent me soon after, accompanying a CD he had recorded of a BBC radio program, ‘Baroque and Roll’, about the influence of Baroque composer Henry Purcell on Pete Townshend’s songwriting. About a year into the pandemic, I began to think that perhaps there was a book about Thunderclap Newman waiting to be written.

I approached Pete to see if he’d be willing to provide input for such a book, and he immediately replied – yes. The degree of Townshend’s fondness for the group took me aback. Here’s a sample quote: “Thunderclap Newman were my invention and my most enjoyable recording session, better than any Who session for me, and as far as I know my only genuine Number One in any role at all in the business.”

Thunderclap Newman alone was a fascinating subject to research and write about. Speedy Keen was a hippie drummer from Ealing who wrote fragments of songs but couldn’t figure out how to finish them. In 1966, he started work as Pete Townshend’s driver. Andy Newman was a telephone engineer for the GPO and a brilliant improvisational jazz pianist who had recorded some film music for Townshend. Jimmy McCulloch was a 14-year-old wunderkind guitarist when he walked into Track’s offices in 1968, holding his mum’s hand, looking for work. The three of them had precisely nothing in common, but a series of happenstance events meant that by late 1968 they gathered in a tiny room in Pete Townshend’s home for their first rehearsal. For some reason, they clicked. Both Townshend and Keen recalled that occasion as “magical”.

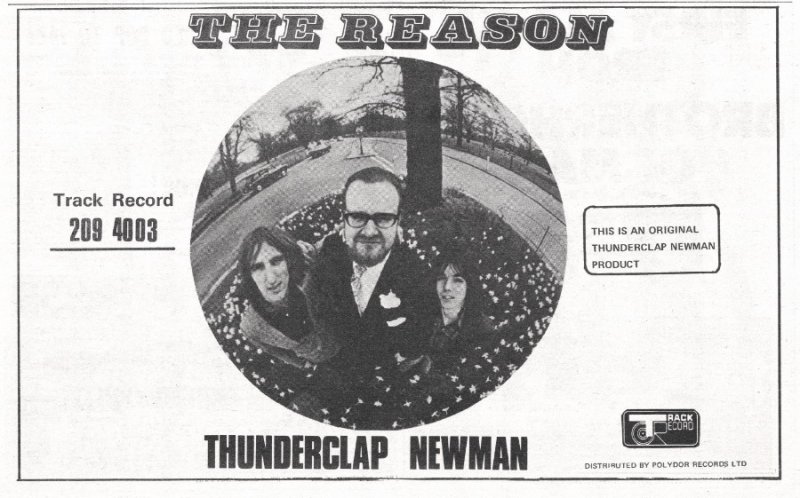

On May 23 1969, Track Records released the Who’s Tommy album in the U.K. On precisely the same day, they released the debut single by Thunderclap Newman, ‘Something In The Air’. Pete Townshend, the group’s mentor, producer, bassist and disciplinarian, immediately departed to the U.S. to tour and promote Tommy. Meanwhile, ‘Something In The Air’ took off, rocketing up the charts and displacing the Beatles from the top spot. Thoroughly unprepared and without their leader, Thunderclap Newman were pushed out onto the road, and in quite short order they fell apart. It was a rapid ascent, followed by an equally rapid decline. There were no other hit singles. A single album, the inimitable Hollywood Dream, was released in 1970, the majority of its tracks recorded in Townshend’s tiny home studio.

There aren’t a great deal of extant written accounts of Thunderclap Newman, with the exception of the U.K. music weeklies during the summer of 1969 when the group were at the top of the charts, and had the likes of Chris Welch visiting them and writing features for Melody Maker. They weren’t around for very long after that before disintegrating. Jimmy McCulloch, of course, famously went on to join Wings, so there’s a fair amount of information about him in the weeklies and magazines of the early to mid ‘70s before he passed away at the tragically young age of 26.

But Speedy Keen and Andy Newman, both of whom are now sadly gone, were a different story. Speedy practically vanished in the late ‘70s after popping up in various odd places – doing a couple of solo albums before producing records by Motorhead and Johnny Thunders’ Heartbreakers. Andy recorded his own solo album in the early ‘70s before working with artists such as Roger Spear and Angie Bowie. Soon souring on the music business, he returned to working as an electrician and helping run the housing cooperative he’d joined in Clapham. Aside from a few reviews of Speedy’s solo efforts, there’s very little documentation of what they got up to after the Thunderclap years. There was a lot to be learned.

By the time I completed research for this book, I had spent endless hours reading through old copies of the NME, Record Mirror and Melody Maker, and had conducted about fifty interviews. I contacted Speedy’s daughter, who graciously allowed me to use her dad’s fragmented and unpublished memoirs, a fascinating window into his endearing personality and his funny and insightful storytelling. I tracked down Andy Newman’s brother and a host of Pete’s old friends from art school, including Richard Barnes, who wrote the 1982 book about the Who ‘Maximum R&B’, which I read so many times as a teenager the binding fell apart. The pages of that then-disintegrated book adorned the walls of my bedroom for years. I spent a surreal afternoon with Barnes in Ealing as he gave me a tour of he and Pete’s past. We found the old Bijou Guest House, a place he and Pete would pass when walking to Ealing Tech, and the source for Townshend’s nom de plume with Thunderclap: Bijou Drains. Barnes also remembered Keen driving past one day, spotting Barnes walking down the road, pulling over and singing him a new song he’d just written: ‘Something In The Air’.

The book is filled with wonderful anecdotes from band members, friends and family and tells not only the complete story of Thunderclap Newman, but of the fascinating lives of these individuals both before and after their time together. Andy’s brother recounts his younger sibling’s destruction of the family piano, a fragile heirloom which had resided, unmolested, in their front room for generations before the heavy-handed ‘Thunderclap’ came along. Jimmy’s bandmate from the early days, Norrie Gilliland, recalled Jimmy’s dad’s quip “I’ll shoot the boots off you!”, a lighthearted reprimand if the boys slacked off during practice. Speedy’s memoirs recount his love for his grandmother, who used to tell him stories. “We used to sit in front of the stove, and she would give me a puff of her cigarette, which was heavy going for a six-year-old. I loved her and I still think I loved her more than anyone else.”

Further information

‘Hollywood Dream: The Thunderclap Newman Story’, published by Third Man Books, will be available on October 1st (US) and November 14th (UK). Details and pre-order links to both the standard edition and a special limited edition will be available on August 30th.