The Hollywood Stars are one of the great lost rock groups of the 70s. Fated for greatness with a sound that perfectly fused hard rock, glam and proto-punk, it was only misfortune that hindered the band living up to their name. With the release of Sound City – an unearthed album recorded in 1976, and a reactivated band, 2019 is proving why they are hailed as LA’s answer to The New York Dolls.

Jason Barnard speaks to Hollywood Stars drummer Terry Rae to hear why it’s taken over 40 years for the group to get the attention it deserves.

Hi Terry, firstly, congratulations on the release of Sound City. You must be delighted with the reception it is getting?

Thank you, Jason. Yes, we are quite happy to finally be getting a degree of recognition after all these years. Outside of Kim Fowley’s essay for Who Put the Bomp fanzine in 1975, precious little has been written about the Hollywood Stars. We were only remembered by those folks who came out to see our shows in the 1970s, and by a select group of “crate diggers” who would come across our vinyl LP over the years. The group is diligently working to turn that around now. Our singer, Scott Phares, has written a Wikipedia page that should post any day, and both Burger Records and our publicist are working hard to get our name out there.

Why has it taken so long for these recordings to be released?

The band broke up twice. First in 1974, then again in 1977. We recorded a pair of albums that were shelved at the time. We had major record deals with Columbia and Arista, neither of which turned out well. So, speaking with complete honesty, the story of the Hollywood Stars has had its share of rough patches. Audiences always loved us, so we naturally felt a great degree of loyalty to our fans. We didn’t want to disappoint them. But inevitably, disappointments did occur. Some were out of our control, but for others, we definitely deserved part of the blame.

At different points in time, the suggestion to reform the band had been posed by various band members, most often Ruben. Eventually, we finished licking our old wounds, got into the proper mindset, and decided to take another shot at reforming. Which meant exhuming old ghosts and a few difficult emotions.

We had been sitting on the tapes for what would eventually become the Shine Like a Radio: The Great Lost 1974 Album and Sound City for many decades. The process to release Shine Like a Radio began when I connected with reissue producer Robin Wills on a UK power pop blog. He was thrilled to learn we had the tapes for that previously-shelved Columbia album and he released it on his own label, Last Summer, and it was distributed by Light in the Attic in 2013. Our bass player, Michael Rummans, was the guy who started the momentum going for us to finally release Sound City.

Much of the material is anthemic like the opener ‘Sunrise On Sunset’ and ‘All the Kids On The Street’. Was this something you aimed for at the time?

Yes, the street anthem style was natural to us and, in general, to the 1970s rock scene. It provided a way to drive home a message with a strong chorus line.

What are your favourite tracks from Sound City and why?

I like them all for different reasons. “Sunrise on Sunset” resonates because it has a solid chorus line and it features our main songwriter, Mark Anthony, writing from a very personal place. It’s at least partly autobiographical. Like so many kids in Hollywood at the time, Mark was homeless. He lived in his VW bug and he initially earned pocket money by running errands for Kim Fowley. So, “Sunrise” brings back vivid memories of Mark. He played a huge role in this band. Mark co-authored our two most famous songs: “King of the Night Time World” (later covered by Kiss) and “Escape” (later covered by Alice Cooper).

“Habits” deals with the lethal 1970s drug scene which claimed so many of our friends and fans. “All the Kids on the Street” is a cool reflection on some of the basic truths we learned from living our rock ‘n’ roll lives. “Houdini of Rock ‘n’ Roll” has a really fun lyric and it reminds me of the magic tricks that Mark used to do on stage. Mark dabbled in magic and Houdini was one of his heroes. When Houdini was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, Mark made sure he attended. Mark passed away suddenly in 2002.

You joined the Hollywood Stars when you were 25 in 1973. What were the key groups you played in and your highlights before you joined the Hollywood Stars?

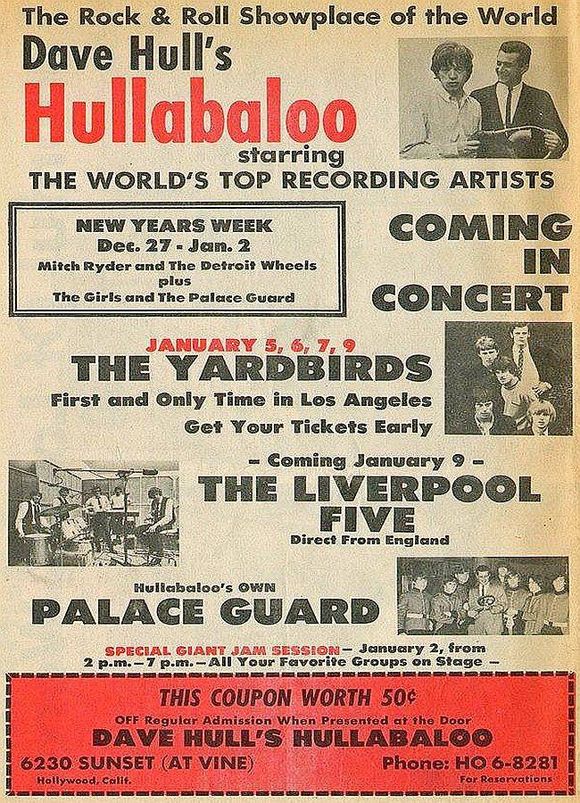

In 1965-’66, I was in a group called the Palace Guard which had a local hit called “Falling Sugar.” There’s actually footage of me playing that track on a show called “Where the Action Is.” You can find it on YouTube. When I joined the Palace Guard in 1965, I replaced Emitt Rhodes as the group’s drummer. We were one of the house bands at the famed Hullabaloo Club on Sunset, and playing every week molded me into a disciplined professional. It was during this period that I learned to sing while playing. During my time in the Palace Guard, we opened for local acts like the Union Gap, the Association, the Turtles, the Liverpool Five, and East Side Kids. Undoubtedly, the most legendary group we opened for was the Yardbirds with Jeff Beck.

In 1967, I was drumming for Sweet Wine. We were popular on the Hollywood scene and played standards by Cream, Bluesbreakers, Buffalo Springfield, and Moby Grape. I met Don Adey during this period which eventually led to my joining the Jamme. The Jamme recorded for Dunhill Records and were produced by “Papa” John Phillips. Lou Adler was also involved with the Jamme. Money was plentiful during this period. But that whole “Summer of Love” period ended when the Manson murders really shook the Hollywood scene to its core.

Just prior to the Hollywood Stars, I was briefly a member of the Flamin’ Groovies and recorded with them. I was on the original “Shake Some Action” and “When I Heard Your Name.” Those demos eventually surfaced on the Slow Death compilation.

How did you get to join the Hollywood Stars – was it through Kim Fowley?

Yes, I was approached by Kim Fowley. We had met at the Rainbow a year prior. We hung out at many of the same clubs. He had the inspiration to put a band together. He had already recruited our original vocalist, Scott Phares. I brought in our guitarist Ruben De Fuentes. Kim knew Mark Anthony and Gary Van Dyke. Gary was later replaced by Kevin Barnhill just prior to cutting the album for Columbia.

Kim had a reputation as a hard taskmaster. What was he like to work with – was he eccentric?

Kim was always a father figure for us. We all had playing experience so we understood when he would explain what he wanted to hear musically. Kim would say “Play it something like David Bowie but on a Keith Richards level.” I suppose it was a strange way to work, but it was a lot of fun. Once we had assembled a strong set, Kim demanded that we rehearse it over and over again. Contrary to all the stories you’ve heard, Kim wasn’t a cruel taskmaster. At least not with us. Don’t get me wrong — he would say crazy, off the wall remarks, but I suppose since there were five of us, we had strength in numbers.

You mentioned the ‘Shine Like a Radio’ album earlier. Why wasn’t it released by Columbia back in 1974?

The Columbia tracks were never completed. The plug was pulled before that happened. At the time, we were advised that there was some problem in regards to billing for studio time. It didn’t help matters that the producer Columbia had assigned to us was actually spending all of his time producing another act. We were left with the engineer to oversee our sessions. Later, Scott learned that Columbia’s East Coast staff had staged a bloody coup on the West Coast A&R staff. As a result, nearly all of the West Coast acts were dropped.

How did you choose the material for the album and what was the songwriting process for the original material?

Kim and Mark had been writing together. Kim had arranged for Mars Bonfire to write for us. Mars is most famous for having written “Born to be Wild” for Steppenwolf. And, if our other group members had ideas to pitch, Kim would listen. Scott, Kim and I came up with “Modern Romance.” Ruben and Scott wrote “It’s Got to be Today.” Kim liked the idea of us covering Danny Hutton’s “Roses and Rainbows.”

Why did the band split and eventually regroup in 1976? How did the line-up differ?

When the Columbia deal ended we were thrown into a very difficult situation. The management team didn’t know what to do with us — they didn’t want to keep paying our salaries. Kim was already looking for his next project.

The band couldn’t continue. Because the songs were now on tape, Kim could begin shopping them to major artists. After Kiss and Alice Cooper recorded two of our songs, we felt a degree of vindication and reformed a year later — without Kim. Scott had already joined Hero by that point, so Mark assumed the role of singer/songwriter/second guitarist. We added Michael Rummans on bass and second drummer Bobby Drier. That was the lineup for the new Sound City album, and the lineup which recorded what would become our self-titled debut LP for Arista in 1977. In tandem with the Arista album, we toured the West Coast and Canada with the Kinks. It was during the period for their Sleepwalker album. We all loved the Kinks and they sounded great. Each audience was different, but in general, it was tough being an opening act. Having precious little time to soundcheck and hardly any room on the stage for us and our gear. I remember the crowd in Vancouver being very receptive and the most open to hearing our songs.

What were the sessions for Sound City like?

Recording with Neil Merryweather was great. He was a good match for us. He was into great guitar sounds and he recreated a true live sound for the bass and drums. The demos we cut with Neil led to us getting the Arista deal. For better or worse. Arista made us re-record the album with their own staff producer and the Sound City tapes stayed in Neil’s hands until earlier this year.

The band broke up soon after the Kinks tour was over in 1977. What did you do afterwards?

Ruben started playing with Steppenwolf in 1979. Scott had left earlier in 1974 and was lead vocalist for a local rock act called Hero. Michael joined the Kingbees, Kevin joined Bandit, and I started playing with Jeff Rollings and Mike Anderson as the King St. Dukes. After the Stars, I also worked security at the Whisky A Go Go, which eventually led to me having a career as a security professional in Hollywood.

When and why did you reform last year? Who’s in the band?

The new lineup includes myself, Scott, and Ruben from the original ’74 lineup. On bass is Mike Rummans from the Sound City and Arista era. Plus, we now have a new 21st century recruit, Chezz Monroe on second guitar and backing vocals. So far, we’ve played three concerts with this lineup, most recently the Whisky A Go Go last month.

What was it like headlining the Whiskey for your first headlining show in 42 years?

Playing anywhere at this point in our history is great! The Whisky was our home base in the ‘70s so that venue has some very special memories for us, and the turnout was great. All in all, a highly memorable night. We’ll be releasing some live footage from the Whisky show soon, so be on the lookout for that.

Hollywood Stars in 2019, Terry (second from right) (photo by Harmony Gerber)

Can you describe your new material – has it been recorded yet?

No, it hasn’t been recorded yet. But we have plenty of material — both old and new — to draw from. We should be booking studio time in the not too distant future.

More information

Sound City archival release arrives on CD and digital download via Burger Records on 23 August 2019.

See also thehollywoodstarsband.com

Photos used with kind permission. No part of this article may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the author.