Jason Barnard talks extensively to Tom Newman and Peter Cook of July about the band, past and present.

July – Tom Newman and Peter Cook

British psych band July burned briefly back in the late 60s. After this initial phase for the group, they thought they were forgotten with the band consigned to history. However July’s profile has steadily risen over the years, their album and single My Clown / Dandelion Seeds (in particular) have met escalating record prices, cover versions and name checked by influential musicians.

I last spoke to Tom Newman, singer of July, and Peter Cook, lead guitarist for July, about six years ago now and there’s been lots of things going on in the world of July. The interesting thing, Tom and Peter, is that the song writing partnership that you had back in the ’60s has been resurrected in recent years.

Tom: Yeah. I can’t remember whose idea it was. Was it yours, Pete? I can’t remember.

Pete: Well, yeah. It all came about when the guys, Los Tomcats, came back from Spain. Tom and John come and knocked me up and said, “Are you still playing guitar?” After the original Tomcats split up I’d sold my Strat and everything else and had bought a crappy old Levin 12-string, so I said, “Well, what do you think, I’ve got a crappy Levin 12-string now” but it got my interest going again and so I started working with Tom. I know Tom doesn’t remember this ’cause I’ve spoken to him about it before, but we got a band together, with a guy called Jim Avery playing on bass, who later went on to become the bass player with Thunderclap Newman and we were writing some stuff which people were likening to Pink Floyd. Actually I’d never heard of Pink Floyd so I didn’t know what the shit they were talking about but we nearly got a recording contract but true to form it fell through at the last minute. However, Tom and I did get a song-writing contract with Chappells. We thought we were gonna make our fortune as writers and we wrote some great songs one of which was for some guy who was a Stanley Unwin wannabe. I don’t know if you remember Stanley Unwin but he mixed up all his words so we had to write a song that had words it like “I like to liss your kips” so that shows you the level we kind of got to, but it was the genesis, if you like, of the songs that eventually landed up on the July album.

The Tomcats – Madrid 1966

Tom: You know Ned, I can kind of remember bits of that but I can’t remember any of the songs we wrote. I mean like, “I like to liss your kips”, although it kind of rings a bell. Have you got them at all on DAT, on tape or anything?

Pete: No. No. It was a difficult time Ned. If you remember it was at the time of Sue-Sue. I know you probably don’t want to say much about that but that that’s when it was all going on.

Tom: Oh. Yeah. Yeah. Maybe that’s why, I’ve got a kind of a blank spot there, you know, over that whole period.

Pete: Yeah.

Tom: I can remember little bits but I can’t remember much about what was actually happening, you know.

Pete: Yes. I must admit, it’s all a bit vague for me too although having to think about for some of the interviews we’ve done, I kind of feel I’ve worked out where it all fits together now, particularly the band with Jim Avery, I remember we waited all in my front room for a call from someone who was gonna say, “Yeah, we’ve got this fabulous deal” but that’s not how it played out and it all fell through at the last minute, which is par for the course. It’s kind of repeated itself ad infinitum throughout our lifetime, we’ve always been waiting for the gear to arrive.

Tom: (laughing) Yeah. We’ve got this thing, Jason, where we say… Oh it was Taylor wasn’t it?

Pete: Yeah.

Tom: What was her name?

Pete: Eve Taylor, Sandie Shaw’s manager.

Tom: Yeah. Sandie Shaw’s manager. She was quite a powerful force in the time of pre-Beatles. Well it wasn’t really pre-Beatles but that very early kind of sixties rock ’n’ roll thing and she managed various people and she kind of took us up for a while, didn’t she?

Pete: Yeah.

Tom: We were always expecting great things, as you do, there was a contract, photo sessions and recordings on offer.

Pete: Well, she wanted us to be Sandie Shaw’s backing band but we said, “No! We’re the Tomcats and we ain’t no-one’s backing band.” ’Cause we’re very smart business people! And we always made the right decisions. (Laughs).

Tom: Yeah. We always said the right thing at the right moment.

Pete: Yeah. Yeah. It’s a matter of principle, you know. (Both laugh)

Tom: Oh dear! Well, actually Ned, I’ve gotta say I’m very glad we did that. I would have hated to have ended up just being known as Sandie Shaw’s backing band, you know. I probably would have had a nice house, a pension and a nice car, but… I don’t know.

Pete: …other than that, who wants it? (Both Tom and Pete giggle)

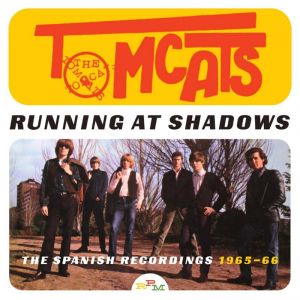

You mentioned Los Tomcats, Tom. A Tu Vera is one of the picks from the new RPM ’Running At Shadows’ album.

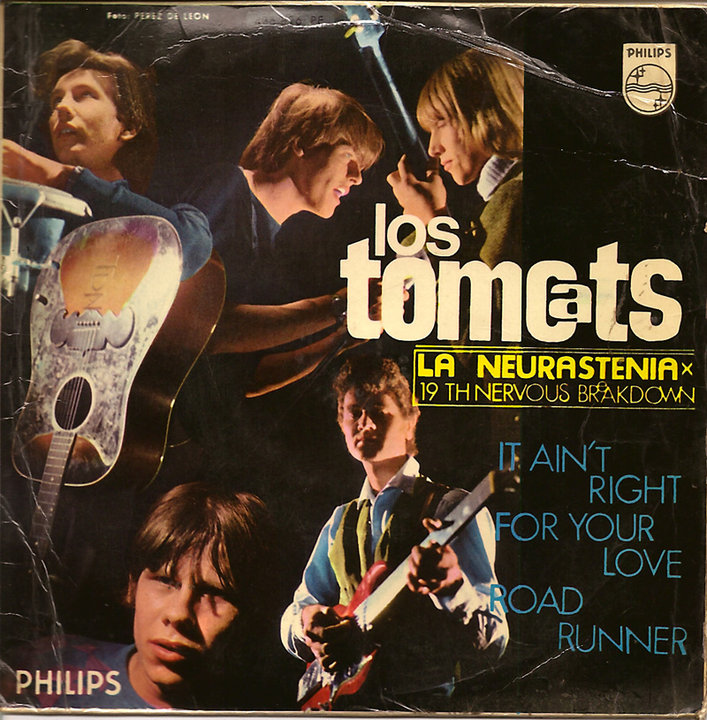

Tom: I know. That’s funny innit? That whole thing was just a bit of a surprise. I thought those tracks were lost in the mists of time really. I think we did about four – three or four EPs when we were in Spain. We went out to Spain because Tony Duhig – he was the lead guitarist in the July band who at that time was in a band in Ealing called The Second Thoughts along with Jon Field, said it would be great opportunity. Originally it was just me from The Tomcats after we had split up because, we’d been working in Beat City and that all went wrong. Do you remember that, Ned?

Pete: Yeah. Yeah.

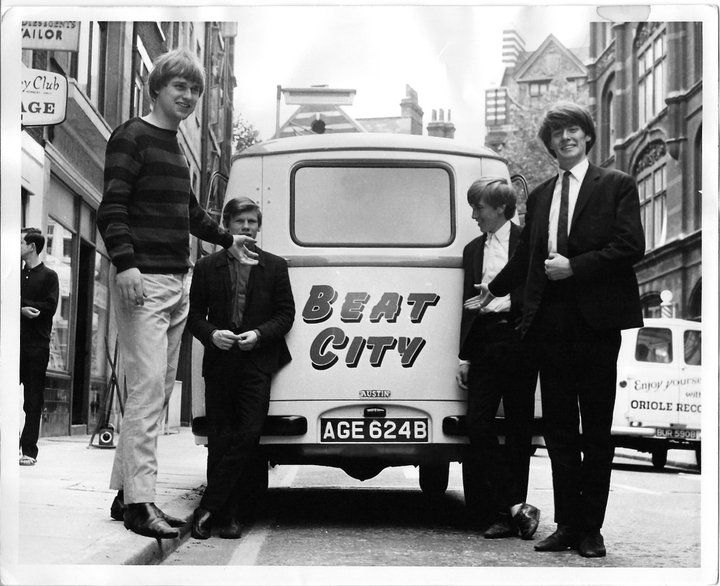

The Tomcats 1964, Tin Pan Alley, Denmark Street, London (Peter Cook far left, Tom Newman far right)

Tom: The whole Beat City thing. We had a whole raft of new equipment: Vox, a whole complete set of lovely Vox AC30s and AC50s and PAs and everything else and we were the resident band in a place called Beat City in Oxford Street, which was a kind of underground night club, and the guy that ran it, and owned it I suppose, a guy called Alex Herbage, he was jailed for some kind of international monetary fraudulent goings-on. So all of our gear got snatched back and the club was closed down, it was one of the instances when it all fell apart. And then Tony, from The Second Thoughts, asked me to join a band that he wanted to take to Spain, ’cause he’d been to Spain in a backing band for someone else and he said it was wide open. This was Spain, still in the period of General Franco, you know, the dictatorship. And so not much was heard of Spain really. It wasn’t like the holiday resort that it became after Franco died. It was still kind of fairly dark really, Spain, ’cause it was the only bit of Europe that remained fascist in the kind of Hitler sense of the word. So we ended up going out there for a month, it was supposed to be, and we stayed there for I think it was about 18 months eventually and we did these three or four EPs for Philips I think it was – Philips/Phonogram or something like that. And we had a couple of hit records out of it in the Spanish charts, you know, but only as covers and I think there was about three or four original songs on there but I can’t remember now. And now all of a sudden it came… I don’t know how they got hold of it but somebody, was it Cherry Red? I can’t remember.

Yeah. Cherry Red/RPM.

Tom: Yeah. They contacted me and asked me if I had the masters or knew who did, I didn’t have the foggiest. I haven’t even got one of the records, let alone know what happened to the masters. Anyway, they’ve got a little deal going with someone. I don’t know how they got the masters or what they cut them from but they’re out now, which is quite amazing really. I don’t even know what’s on it. Is it an album or is it just a…?

Yeah. It’s a pretty comprehensive comp. I’ve got it in front of me.

Tom: On a compact disc, that’s right. It’s not on vinyl is it?

23 tracks, although they’ve got a few from The Second Thoughts on it.

Tom: Oh yeah. That’s right. The Second Thoughts.

So Peter, you’d left the group by then?

Pete: Yeah. After the collapse and the disappointment after Beat City, I got disillusioned and went off and done other things. Obviously Tom didn’t get as disillusioned as I did and carried on with Chris who joined Los Tomcats as well and they sodded off to Spain without me, they forgot me and left me in the wilderness… the rock ’n’ roll wilderness. (All chuckle)

Tom: Chris didn’t come originally, did he…

Pete: He did, it was Alan (James) who joined later when you were over there.

Tom: Yeah. That’s right. Actually, the band that was supposed to go to Spain had Speedy Keen from Thunderclap Newman….

Pete: Right.

Tom: …as the drummer and we did a gig at Ealing Town Hall to pay for the road trip to Spain, ’cause there was no flying. We took the van, you know an old J2 van with us. And we were supposed to leave at the end of the month. We did this gig – I can’t remember what month it was – and for some bizarre reason Speedy had looked after the money; but Speedy wasn’t the kind of guy that you could actually trust looking after your money (laughs) and Speedy pissed it all against the wall and so, about two weeks later, when we found out that we didn’t have enough money to get there and back – because the idea was we would go there but make sure we had enough money to come back just in case it all went tits up – as Speedy had spent the money, or most of it anyway, we had to do another departure gig. It had been all set up at Ealing “The Departure Of The Tomcats Off To Spain” and then we had to do it again to get enough money to come back. It was a real farce. It’s the sort of thing that could have actually been done as a kind of Spinal Tap thing and it would have been quite funny I think (ha ha ha). So, as soon as Speedy revealed himself as being thoroughly untrustworthy, we sacked him and got Chris Jackson in. So it was me and Chris Jackson, from the Tomcats that went to start with and then the bass player we had was Mickey Holmes from The Second Thoughts and, I can’t remember how he departed but we got fed up with him or he got fed up with us it might have been – I can’t remember. He wasn’t very good at certain sorts of rock ’n’ roll that we were doing at the time, I think, and they were the kind of things that Alan was very, very good at – kind of sort of boogie riffs and stuff like that – so we got Alan out and that was the Spanish band.

Another favourite of mine from the Tomcats’ compilation is the title song, Running At Shadows. Is that written by you, Tom?

Tom: Yeah. That was the first song I ever wrote and, actually, I’d completely forgotten it until Cherry Red reminded me about all that period and, when I saw the track list that they wanted to put out I thought “That rings a bell” and I actually haven’t heard the re-mastered version of it and somewhere I’ve got the original bit of paper I wrote it on. Yeah, that was the very first song I ever wrote, very angst ridden. You know I was about 14 or 15, I think, when I wrote that. I’ve got a feeling it was over being dumped. I got dumped by a girl called Gloria Bucknall who lived two doors away from me in Perivale and she dumped me because I – I had long hair, like the Everly Brothers, ’cause I wanted to look like an Everly Brother, but then the headmaster at the school, he stamped down on the whole long hair stuff. It was frightening him, so he sent everyone with hair that went over their ears round to the barbers in Ealing – this was Ealing Grammar School – to the barbers in Bond Street in Ealing and we were all given compulsory crew cuts. So, when I went to meet Gloria coming out of her school, ’cause she went to Ealing Grammar School For Girls, I went to meet her on my bike after school and she took one look at me and dumped me on the spot and that was that. It was my first real, you know, recognition of just how brutal girls can be when they don’t get what they want. Sorry Jennifer, I’m not talking about us.

Pete (chuckling): He’s never got over it. He’s never ever got over it. He screams it out in his sleep.

The Tomcats, 1963, Ealing Town Hall West London (Tom Newman far left, Peter Cook far right)

Tom: It was a hard lesson (laughing). I still can’t remember how we got back together when we got back from Spain, I can’t remember how the band ended up doing the July album, really. There’s a whole blank period in there. Pete wrote all the songs, well nearly all the songs. I only wrote about three or four songs on the July album and I can’t remember how all that happened. I’ve got no recollection of how we rehearsed them, how they arrived in the repertoire. I’ve got one recollection of the actual recording session because, although we’d been in recording studios before, this was the first big time studio we’d been in with a real record producer, a guy called Tommy Scot, a Scottish guy. He was Scots as well as being called Scot and it was CBS Studios in Warner Street, it was the first big time studio I’d seen, they had great big 4-track Studers. It was the same kind of setup as The Beatles. We recorded on two 4-track Studers, bouncing between one and the other to get all the bits and pieces on. So, it was a very exciting – and that’s probably why I remember it although I had terrible flu at the time so I sang like a wanker and I hated the album. The final mixes, I actually bloody hated them and in fact I hated the whole album for many, many, many years right up until I think it might have been Pete phoned me and said, “You know that album’s worth a thousand quid now” and I couldn’t believe it. I still hated the sound of the album but then there’s a great Spanish record company called Guerssen – they actually re-issued a re-mastered album and they remastered it amazing well.

Pete: It was Cherry Red that did it first on CD and then Guerssen took it to vinyl.

Tom: I didn’t think the Cherry Red one was re-mastered.

Pete: Yeah. Cherry Red re-mastered it. I can’t think of the guy’s name now who done it.

Tom: Oh, really?

Pete: Yeah. Yeah.

Tom: So the job that you hear on the Guerssen album is actually done by Cherry Red?

Pete: Yeah. Yeah.

Tom: Oh wow! I didn’t know that.

Pete: Yeah. But the July thing. We’ve often talked about the bits that you don’t remember when we hooked up again after Los Tomcats, like having a band with Jim, writing songs and the writing contract with Chappels. Then, Sgt Pepper come out and we were so knocked out with it that you, me and Jon Field started to meet at Jon Field’s house to listen to the Beatles stuff and we toyed with the idea of getting a band together and that’s when all the material started coming forward from us, what I didn’t know and I don’t think you knew at the time, was that John was still playing in a band with Tony and Alan….

Tom: Yeah. I didn’t know that.

Pete: …and Jon cut me out, you know I’ve sorted it out with him since, we’re OK with it now but we’re both strong personalities and I must admit that I was a bolshy shit at the time, well I guess I still am basically…

Tom: I know.

Pete: Jon didn’t like the fact that I had strong ideas and I was, kind of like more rocky and he was slightly more, kind of, weird – which is why July worked – and suddenly I was dumped off the scene and Los Tomcats re-emerged as July. I know they were recording stuff at the organ shop in Ealing but I was banned from the sessions because obviously they, they being Jon, thought I would start interfering and giving my views, so it kind of ended up – it wasn’t a very nice period of time. I was a bit bitter but that’s rock ’n’ roll innit – that’s rock ’n’ roll, water under the bridge.

July in the middle of the road on Horsenden Hill, Perivale, Middlesex. England.

So who wrote Dandelion Seeds and what was the genesis?

Pete: The maestro wrote that one.

Tom: Did I write that?

Pete: Yeah.

Tom: Oh, Dandelion Seeds. I haven’t the foggiest idea where that came from. The only thing I remember about it was the rhythm guitar part, I’d started to listen to John Lee Hooker and I was very affected by his kind of pushy, very simple E-minor sort of ’jomp d-jomp d-womp d-wat d-wat d-womp’ sort of rhythm that he hacks through, you know, on several of his songs, that was the way I saw Dandelion Seeds and my recollection is that it got picked up by Jon and Tony and kind of fiddled with.

Pete: They done a brilliant job in fiddling with it I’ve got to say.

Tom: Well, I don’t know. I’ve tried to remember exactly what happened but I can’t genuinely… I can’t say that I really remember much of it but I didn’t like… I hated that whole dreary middle bit where it sinks into something else. That was, I’m almost sure Jon’s idea.

Pete: Yeah. That’s got to be Jon. That is Jon. It’s got Jon written all over it, hasn’t it?

Tom: It’s got that kind of mark on it hasn’t it?

Pete: Yeah.

Tom: And I hated that at the time and even now it’s very difficult to do live. You know, the couple of gigs we did this year – when we first started to do live stuff, you know when the band reformed – must have been three of four years ago now – we spent quite a lot of time trying to recreate what was on the record but it’s ever so difficult. And the last couple of gigs that we did, which I really enjoyed, were the gigs where we said, “Ah fuck it. Let’s not fuck about trying to get it like the record. Let’s just treat it like a jam and let it take its own course, and see” because the band we now use, our little backing band is the Sonic Jewels, they’re young lads and it’s very difficult to get young lads to focus on a proper arrangement, straight off a record. You know, they can kind of do it in rehearsals but then, when you put them on stage, all that goes out the window, they forget about all that because they get excited by the occasion and the audience and all that and any arrangements that had been. Pete’s the sergeant major when it comes to July rehearsals and he makes us go through the set time after time and he hacks the arrangements up and he makes sure that we all know exactly where we’re supposed to do what and he’s very meticulous. It drives me mad, and it drives the band mad, but it’s the right thing to do, of course it is but, when you’re 72, it’s hard to know what the bloody hell is going on. So, with all of that rehearsal time, when we actually get on stage (chuckles) only about 10 per cent of it gets through, so we’re winging it.

You know, when July go on stage – amazingly it always works. Every gig. We’ve never had a bad gig and they’ve always been packed out and they always rock away. I love the gigs. I really, really enjoy the gigs and, what amazes me even more is that all down the front, there’s 60 or 70 people down the front, all of them young enough to be my grandchildren and they know the words better than I do. They’re singing along with us. The other thing about the gigs, of course, is that the words for my songs are relatively easy ’cause I was never a great wordsmith but Pete, he picked up this amazing ability to kind of home in on the whole of that psychedelic period incredibly well, lyrically. So, even on the July album, the songs that Pete wrote, are packed with very complicated, really bizarre, surreal bunches of words that I’ve finally kind of got my head around, now I can remember about 99 per cent of the words of Pete’s songs, which I never expected I’d ever be able to do but the little girls and boys down the front of the July gig, they know ’em all. They actually tell me off if I get ’em wrong. Afterwards I’ve been approached by the odd kid who says, “You got the second verse of A Bird Lived the wrong way round and you put Peg Leg’s Sears where Dumpling Joe should be” and it’s very bizarre.

Pete: Well you know all the words, Ned, but not necessarily in the right order.

Tom: Exactly. Yeah. (Chuckles)

Pete: You remember the gig we did in Gijon where the air conditioning blew all the fuses during My Clown?

Tom: Oh yeah.

Pete: …and everything went off and all the crowd there just carried on singing it through. That was kind of amazing.

Tom: Yeah. So we did kind of half of My Clown with just me playing acoustic guitar and the crowd singing the song. It was brilliant. Actually… it’s amazingly… When you’ve spent a whole life trying to be a rock star and completely failed every single time and then, all of a sudden, you reach the age of 70 and you play in front of an audience in Spain who you never expected to have ever heard of you, let alone your songs and the band and the album and all that and all of a sudden you find yourself playing in a psychedelic festival in Spain to people who not only know the songs, they actually know them better than you do (Pete chuckles) and you go down well. It’s fantastically rewarding. I mean it’s like dying and going to heaven ’cause you think, “I still haven’t got any money. I don’t own a house. I haven’t got a new Harley.” But, nevertheless, it all kind of works out OK, you know. It’s a very strangely, I don’t know, there’s something fiendish about it. It’s like being kicked in the teeth and patted on the head at the same time.

(Both Pete and Tom crease up laughing)

Tom, what’s this about you being on the roof when The Beatles were doing their rooftop concert? Didn’t your painting have a starring role?

Tom: That was a funny situation. That was just after a terrible thing that happened to me as Pete referred to earlier. I had a girlfriend who died of an ectopic pregnancy and it really set me back psychologically and emotionally for several years and I, out of that, had started painting. I’d kind of given up the idea of writing music or being involved in the music business completely. I was doing these paintings that were kind of science fiction, Star Warsy sort of planets – planets with lots of moons. Odd stuff like that. I was living in a weird fantasy world at the time and I had this idea of just trying to just make a living really and, of course, I was still incredibly a fan of The Beatles and everything that they did and I decided, one morning, to take a couple of paintings up to London and see if I could get into the Apple headquarters in Savile Row. I was kind of mincing up and down the road with these paintings under my arm trying to see if I had the balls to actually go up the steps and bang on the door, a van was parked outside unloading equipment and I just walked by this guy got out of the van and said, “Tom. What are you doing here?”, it was a guy called Adrian Woolf who lived in our street where I lived in Perivale. Do you remember Adrian Woolf, Ned?

Pete: Yeah. Yeah. Went to school with him.

Ned: Oh well, there you are. See. Anyway, I said, “Adrian, what are you doing here?” He said, “We’re filming the Beatles, they are gonna play on the roof.” I said, “Fuck me. You’re kidding” and he said, “No. No. Here.” and he gave me this little tiny flight case with some lenses or whatever it was in it and he said, “Here you are. Grab hold of that and come in and I’ll get you in.” And I was shitting myself, of course, but I just followed him so I became Adrian Woolf’s roadie for about half an hour, taking crap into Apple and going up the stairs about four or five times right up to the roof. There wasn’t a lift so we had to use the stairs and I couldn’t believe it, it was like walking into the Magical Mystery Tour, there were all these little dolly birds and geezers with trendy flairs on (chuckles), straight out of Carnaby Street and, amongst them, there’s the Beatles wandering about. So I helped Adrian up with all this equipment and Ringo’s drum kit was set up there so I put this painting that I wanted to see if I could sell, this kind of space-age thing, behind Ringo’s drum kit and I just hid on the roof ’cause I thought I’d get chucked out by Mal Evans who was wandering about with Neil (Aspinall) if they didn’t recognise me. But I suppose I looked fairly groovy ’cause I had Beatles haircut like we all had anyway, so I could have passed for any groover (chuckles) and everyone in Apple all looked similar so maybe it was just that I never got picked on.

Anyway they came on and it was an amazing, amazing gig. I’d never seen them live before – ever – so I was amazed at just how much like The Beatles they sounded. You know, I mean, but not just like The Beatles, it was spot on, there was no mistakes, it was absolutely perfect. They played Get Back and, in fact, they were recording it as well, I didn’t know that at the time but they were recording it in the basement. Actually, I used their basement studio a few years after that to record Paul’s brother, Mike McCartney. The version that came out on record of Get Back is the one they did on the roof, as far as I can make out. I haven’t checked it note for note but it’s got all the nuance of the live version and they were just playing through little tiny Fender, you know, little baby Fender amp and a Fender PA system and they were just miked up with half a dozen mikes and it was the best fucking rock ’n’ roll sound I’ve ever heard really. The cops came out and complained because of the noise but actually it wasn’t really very loud, it was just that they were scared that it was kind of revolutionary what they were doing and, at the time of course, there hadn’t been a revolution yet. But it was an incredible experience, it really was amazing, and bizarrely I sold the painting. I got 25 quid for the painting from Neil Aspinall who, bless him is dead now, but 25 quid in 1969, or whenever it was, ’70 was a lot of money, it was more than I’d ever had in one go anyway (chuckles). So that was that.

Talk about right place, right time.

Tom: Yeah. Oh absolutely. Yeah. That was the only one, the only time I suppose I’ve ever been in the right place at the right time. (laughing) Oh dear.

I was talking, Tom, about right place, right time as well. Your link up with Mike Oldfield seems very much the same sort of scenario where, was it, Mike took some demos to you?

Tom: Yeah. Yeah. Somehow that hasn’t quite got the same importance to me. That’s not to play it down, I know a lot came out of the whole of that Tubular Bells thing ,but it wasn’t as much fun as going on the roof and The Beatles playing…

Pete: …sorry Michael, but you know…

Tom: I think the reason that it didn’t impress me at the time was because it was all new, I was expecting it to fail rather than succeed and really, even though I loved what Michael was doing and I pushed like mad for Virgin to release it, I didn’t expect it. I was 30 when I did Mike Oldfield and I’d spent the majority of my youth failing (laughs raucously) and, all of a sudden and through no fault of mine really, the Mike Oldfield thing took off. It was definitely because of me up to a point because he wouldn’t have got the deal had I not plugged the record, the demo that he played me. It was Richard Branson that made that happen because of the amount he put into promoting something that, bless him, he had no idea what it was. Richard wasn’t into music at all, so, he was promoting something that he had absolutely no concept of, so that really took a determination to succeed which I was staggered by really. I’ve got all the praise for Richard for making that all happen. Yeah. That was cool as well but not as cool as being on the roof with The Beatles. (chuckles)

How long did it take to record the album ’cause there’s all the talk about the number of overdubs et cetera?

Tom: Oh that’s a load of bollocks, the number of overdubs got inflated by Richard almost immediately. He was talking about 2,000 overdubs, it was nowhere near it. I don’t know how many overdubs can you get onto a 16-track tape? I suppose the most we ever did over one section would have been probably, oh maybe, 25 to 30. It depends how you count it. If you look at the whole album and look at everything that got recorded as an overdub, because there was only two bits of it that were actually live and that was the Cave Man song and, well, that’s about it really. The rest of it was all stitched together from two or three overdubs and then built up over that so I’d be surprised if we did any more than 100 overdubs really. Richard made all sorts of outrageous claims, that’s what the music business was about, you talked bullshit and people believed it but thankfully I never had to do that, I couldn’t have done that, I just wasn’t into that kind of stuff, I haven’t got that kind of persona to be able to big something up in a blatant sort of music biz way. So, no, that’s a load of crap. It was good, I enjoyed doing it and I’m ever so glad it went where it went.

I got a lovely letter from Richard not that long ago – last couple or three weeks ago and I can’t remember what it was about now but I’d talked with him over something or other and he said, “Well if it wasn’t for you I wouldn’t have the responsibility of feeding 80,000 people right now!” He’s got 80,000 people on his payroll, I thought “You poor fucker, I’m glad I’m not you ’cause I can live very, very happily and freely on £150 per week.” (breaks down laughing) Bless him. Oh dear me.

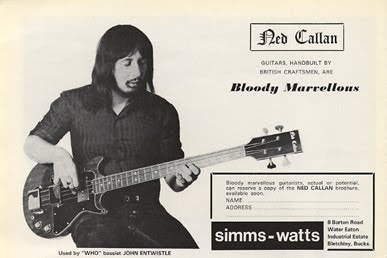

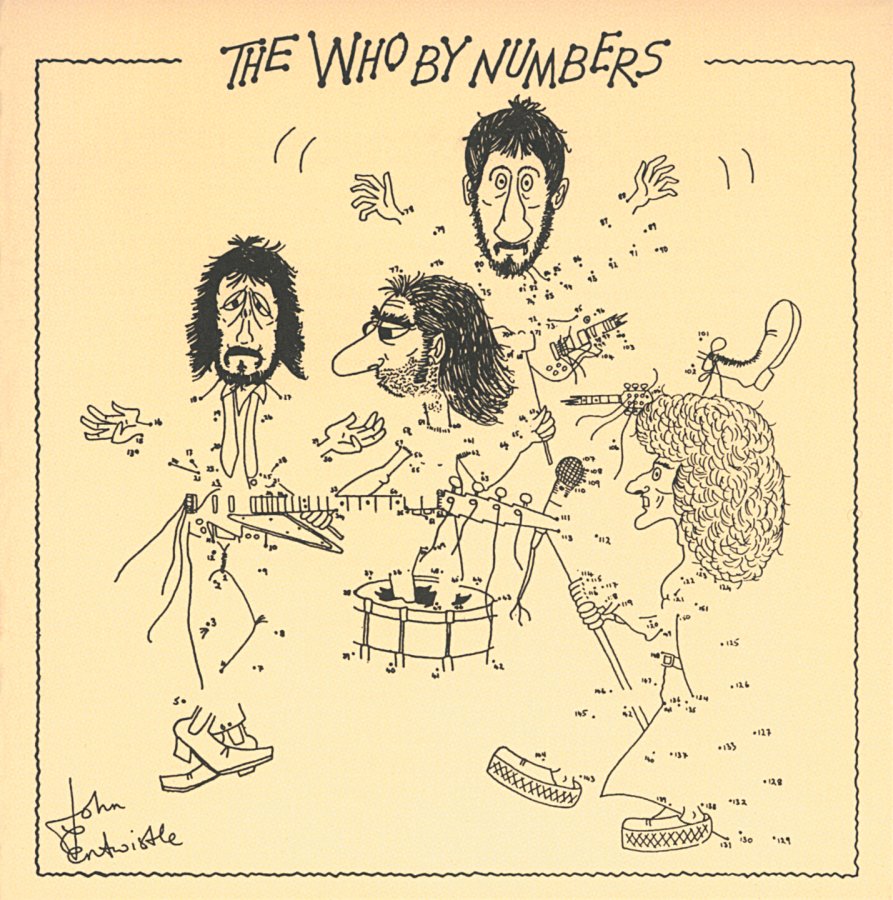

Peter – you’ve become a very renowned guitar maker and you have a guitar shop which is very well known in the business. You made John Entwistle’s bass.

Pete: Well quite a few of them. I started off again when the rock ’n’ roll option wasn’t available to me after July. Something that Tom and I had started to do in the in-between times when we didn’t have any sort of major projects was fiddling around on guitars to try to feed ourselves and we’d made a few prototypes from some necks that Tom had bought and found in a second hand shop in Edgware or somewhere, I don’t know exactly where, and we made up some guitars.

Tom: Weren’t they Harmony necks?

Pete: Yeah. We had this plan that we were gonna make production guitars and we had serious discussions with an interested party, I’d drawn up this business plan – complete fantasy really about how we were gonna manufacture and sell them but true to form that kinda went by the by. I then decided to carry on trying to do just that and I developed the Ned Callan range, I used to hang around in the Ealing area where there was a shop called the Musical Bargain Centre, John used to go into the shop ’cause he lived around Ealing as well and he kind of quite liked the basses I was making. He had done a deal with Simms Watts to promote their bass amps, Simms Watts were also distributing my guitars and as John liked them he decided to promote them as well. So there are some early adverts of him with one of the Ned Callan custom basses. Soon after he started to call me up and say “Can you mend this guitar? Can you mend that guitar?”, he had loads of bits and pieces. It became pretty clear that he liked the Thunderbird body shapes but he preferred the Fender necks, the precision necks. So we started putting together some Thunderbird styled bodies mixed with Fender necks, we called them the Fenderbirds, I ended up making quite a few of those for him in different colours, I developed the range by remodelling the body in an Explorer shape and called them the Explorer-birds. And then it started getting kinda weird, John would say, “Can you make me a guitar like an axe?” So I’d say, “OK. Yeah, yeah” so I made him an axe which he then used in the film Tommy. There’s a scene of him, like a church scene and he’s playing the axe. He then said, “Can you make me a guitar like a streak of lightning?”, so I said, “Yeah. Fine” and I made him a guitar like a streak of lightning which was caricatured on the cover of the Who’s “Who By Numbers” if you join all the dots you uncover the Lightning. “Can you make me a guitar like a cartoon flame?” So, yeah, of course, I made him one. Many of them went to auction some time afterwards and sold for phenomenal sums in those days and one of them, and I think it was the flame, sold for $33,000 and then resold a few years later for $44,000, for a while it held the Sotheby’s record on guitar sale prices until one of the Jimi Hendrix Strats come up for auction and blew my record out of the water, at least I had held the record for a while, so that was good fun.

Tom: I didn’t know that Ned. That’s amazing. Brilliant.

Pete: It’s weird. The guys who worked in my shop in the shop at the time were all trying to wind me up by saying “Are you gonna go to this auction? They ain’t gonna sell those guitars” (Big laugh) but I came back with a great grin on my face shouted “You never guess how much those fucking guitars had sold for.” Unbelievable, unbelievable, nothing to do with me really… I mean that they was John Entwistle’s. I worked with John quite a lot and used to go along to the who’s rehearsals and sort stuff out for him and, obviously, Pete Townshend. Pete’s roadie used to bring me loads of broken and fucked up guitars, I mended so many of them with broken headstocks but then Pete wanted his stage guitars, his numbered guitars, to all feel and play the same. He’d got this thing about having three pickups and had picked up a bucket load of pickups in the States, I think they were DiMarzios. He wanted me to fit them as a third pickup to all of the numbered Les Paul’s, I also profiled all the necks to the same specification and removed the volutes because he didn’t like them. As part of fitting the third pickup in the middle I installed an extra row of controls and switches although I can’t remember what they all did now. It was a ridiculous amount, six knobs, four switches and three pickups, I can’t imagine why he’d ever want that but he did so he had a whole load of them, so that that was a bit of a laugh. Pete asked me to go to the States with him on one of their tours but I had a young family, it was coming up for Christmas, I had a business in the custom guitar world, so I said “No. I don’t really fancy that.” Along came this guy who snapped up the opportunity, a guy called Alan Rogan who’s now the guitar tech of the stars. He’s travelled with everyone, anyone you like to name, every famous guitarist Alan’s been out with ’em and he’s a proper guitar nerd in that sense, so good luck to him. That could have been me, although I doubt it because I’m not that sort of guy really, but that was one of the opportunities – the doors that opened for me. Normally someone else shuts them for me but that was one I shut myself.

Tom, you made an excellent album, Fine Old Tom in the 70s.

Tom: Oh blimey.

Good record.

Tom: Thank you very much. Nobody else has heard of that. You’re the only person on the planet apart from me who’s ever heard of it. Oh, except for Pete’cause he played on it. When we recorded that at The Manor, Pete came down and we locked him in the khazi with a harmonica at one point. What was it? I can’t remember what it was he was playing on.

Pete: Well there was a couple I played on wasn’t there. Again, one of our weird bands came out of it, we formed the Tomcats again for a while, do you remember, with John Varnom….

Tom: John Varnom.

Pete:…and Ted Macdowell, we had this stage act where we had a dummy on stage that everyone used to beat up. It was really quite funny and there was…. I’m trying to think of the names of the tracks that we played…

Tom: I remember that. That dummy.

Pete: …and obviously there was Superman, which is a track that I’d written and I played on as well, which was weird. Weird things (laughs) we’re always trying at every opportunity to be rock and roll stars.

Tom: Yeah but I mean the amazing thing was, we kind of followed the zeitgeist of rock and roll in order to be accepted and then we fucked it up by putting the wierdest songs in the middle of something that just didn’t match.

Pete: Yeah. Yeah.

Tom: There was a determination to self destruct, I think, all the way along Ned.

Pete: It’s worked. It’s a plan that’s absolutely worked.

Tom: The only successful thing’s that we’ve always managed is to fail. (Both break down laughing)

Pete: It’s not an easy thing to do that, despite the compliment.

Tom: No.No. Not considering the number of opportunities we’ve had. Most people only get one opportunity. We’ve had twenty and we’ve very determinedly fucked them all up. I mean that could be a Guinness Book of Records attempt Ned.

Pete: Yeah, definitely, yeah.

Tom: I just realized something else that I forgot I was gonna mention that earlier. I saw on Facebook that Julian Lennon…

Was that Sean Lennon?

Tom: His favourite track of the psychedelic era is July – Dandelion Seeds, I think. Was it Dandelion Seeds?

Pete: Sean Lennon. Yeah.

…in Rolling Stone. Yeah I saw that. It’s really cool ’cause he’s a great artist in his own right, actually, is Sean Lennon.

Tom: You know I’ve never heard anything that he’s ever done.

Check out the project he did called The Ghost Of A Saber Tooth Tiger.

Tom: Oh yeah.

That’s great.

Tom: I haven’t actually heard it but I’ve heard it said. I’ve heard the name.

That is superb. Some of it’s a bit Pink Floyd.

Tom: Really?

You also carried on working with Mike Oldfield, including his big hit Family Man.

Tom: I didn’t actually do that.

Didn’t you do that? Sorry.

Tom: I don’t think so.

It says on the internet that you did but obviously that’s not always right.

Tom: I might well have done. I’ve got no idea. I remember the name of the song. What album was it on? Do you know? Is it obvious?

It was from the early… Five Miles Out, actually.

Tom: Oh yeah. Ok. Yeah. I did do it. Yeah. (both laugh) I can’t remember it. I mean, you know, Michael, he’s a brilliant genius instrumentalist but he’s only written about three or four songs that I think are worth shit really. Five Miles Out, the song, is one.

It’s brilliant because I had a lot to do with the way it was constructed. I was talking to the guy from the Prog Rock magazine earlier this week about it and I had a sudden burst of self confidence and almost bravado and hubris, if you can have hubris at 73. It occurred to me, by the way that he questioned me, that actually that Michael best tracks are the ones that he’s let me have quite a lot of influence on and his best track in my eyes is Five Miles Out, without a doubt. I mean Moonlight Shadow is brilliant, but I didn’t have anything to do with that, so that’s his second best song but the worst period of my life with Michael was undoubtedly doing the Heavens Open album which was all his songs and, although I produced it, I didn’t have the influence that I had when we did Five Miles Out. We were working with Simon Phillips who’s a wonderful drummer but put Simon and Michael together and they turn into bizarre control freaks, they became obsessed by minutiae of tempo and what they lost sight of is “what’s the song about?” You know they got completely wrapped up in the musical need to have some kind of musical one-upmanship and validity and they forgot what the lyrics were saying. So, to me Heavens Open was not a good album because they were more interested in creating something that other musician nerds would go, “Wow man”. They forgot what the songs were meant to be about. But on Five Miles Out, the reason I love that so much is that it was from a direct experience, a really scary experience that Michael had very recently had in an airplane, because he’d just learnt to fly, and he was taking his twin – he learnt to fly on a single, obviously – and then he took a twin certification and he ended up in a really, really bad cumulonimbus and it scared the life out of him. I’ve got feeling after that he didn’t fly any more, I think it scared the shit out of him, but he wrote this song about and it was a very powerful song and what I’m proud of is that I never let him forget what the song was about so the dynamics of the song are really locked on to the emotion rather than the musical virtuosity, if you see what I mean.

You’ve made quite a lot of instrumental tracks. One your recent songs that I like is off The Secret Life Of Angels album – Raphael’s Bicycle.

Tom: Thank you very much. Secret Life Of Angels, well, yeah I keep plugging away at trying to make albums that just come out of my imagination you know, and The Secret Life Of Angels is about, well I’m always confused about the whole deal because I love science, but I was brought up as a Catholic in a Protestant school, so I’ve got a real confused God-head in my head. Science kind of denies the concept of an old man in a white beard sitting on a cloud concept of God. I mean, religion obviously is a nightmare throughout the world, if religion could be got rid of the whole world would be a better place now, I think. Despite that, you know, if you grow up through a culture where religion is a replacement for genuine primordial superstition, which is what it became and then science starts to burst in, which it did into my life. I was right on that cusp of being a war baby. Science started to take over from religion in the ’60s and ’70s and now science has taken over completely, in my eyes, but I still have this enormous reverence for spirituality. And to me, the idea of angels really appeals to me and I’ve got a real faith and belief in some kind of angelic intervention in my life because, you know, I’ve done so many absolutely lethally dangerous things, you know, on motorcycles. When I was young I was a complete lunatic and I don’t know how I’m not dead. It really amazes me, I’ve done things that you wouldn’t believe in cars and motorcycles. I mean, I drove from Notting Hill Gate to The Manor in Kidlington in 38 minutes in an E-type Jaguar before the motorway was open and I was completely pissed and yet I made it. You know that wasn’t a one off. I’ve done that more times than I would care to own up to a policeman and thank heavens you can’t retrospectively nick someone for driving drunk when they were young, especially if they didn’t actually do any damage so I’m kind of, I suppose, in the clear.

I really believe that I’m being looked after and kept alive by some force beyond my own stupidity, I mean despite my own stupidity and the Secret Life Of Angels was very much about offering some kind of something to the angels by way of trying to make the concept of angels more acceptable. And the idea is that, on the album at least, that the angels are trying out things that ony humans… The angels are obviously immortal and kind of “airy”, they’re spiritual beings and their job is to look after humans but the one thing they can’t understand and don’t have any real knowledge of is mortality. Because they live forever, I think the angels would have a fascination for ‘how is it possible that these human beings get born, they last for about five minutes in cosmic time and then they die and yet they manage to learn and give out such an enormous amount in terms of creativity – you know, music and poetry and the writing and Shakespeare and the study of science and yet at the end of that they die, almost immediately?’ As far as an angel’s concerned, they’re only here for a few minutes and then they’re dead and yet they still dive at life with such gigantic enthusiam and such enormous commitment to the wonders of it that the angels are really, kind of jealous of them in a way. And the idea behind Rafael’s Bicycle is that he persuades God to let him become human for a day just to see what it’s like to have to learn to do something in human terms. So what he’s doing is learning to ride a bicycle just like a human would learn to ride a bicycle and, you know, he keeps tripping up and falling off and coming off the pedals and ringing the bell and, so it’s really just a little tone poem about the idea of a mighty archangel relinquishing all his powers just to see what it’s like to be human for five minutes.

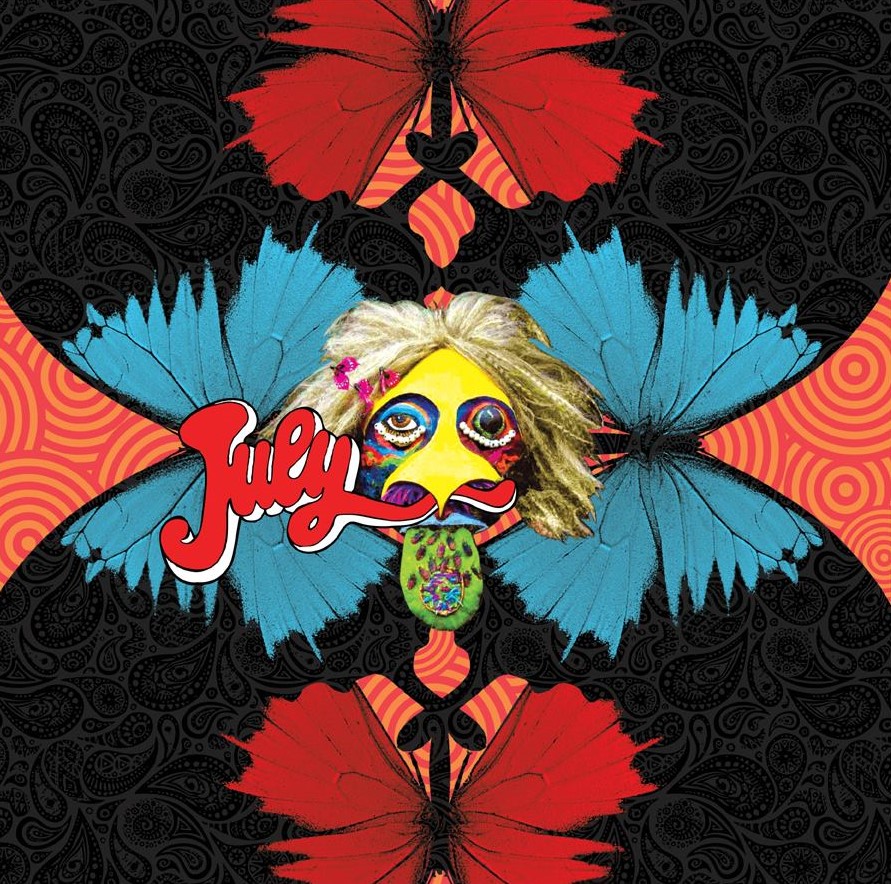

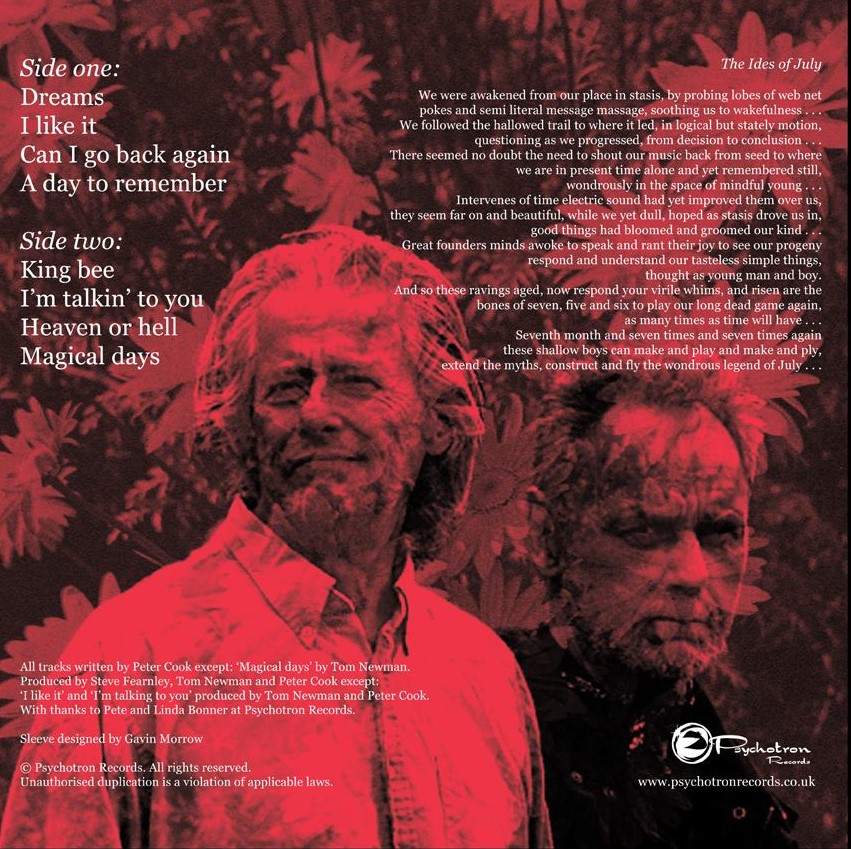

Next let’s move on to the Resurrection album by July. It’s being released on vinyl on Psychotron Records. A Day To Remember is a great song about living for the moment – today will soon be gone, make the most of things.

Tom: That’s Pete’s entirely. He’s always managed to capture that zeitgeist of that ’60s psychedelia thing and we talked long and hard when we first came together again after many years and decided to write another July album. We talked long and hard about what the concept would be and the idea was that we’d been in stasis, in some kind of strange artificial stasis, and we’d been called out of stasis but our heads were still in 1968. You see what I mean? So we were writing ‘60’s songs in about 2000 or whenever it was we did it – eight or ten or something. When did we do it? I can’t remember Ned.

Pete: Yeah about that, I think. (both laugh)

Tom: But with the attitudes that we had when we were young. See what I mean? And Pete was brilliant at that. I was fucking useless, I tried a few ideas but I couldn’t get anything together and so Pete wrote nearly all the songs on Resurrection and he did an amazing job. It’s a brilliant album. I’m really pleased. He got to grips with it and forged ahead, you know.

Pete: I’d become a right pain, to be honest, because as Tom said you’ve gotta take yourself back. We were aiming to be in ’68 again where our heads were, not like as old farts trying to croon and prove that we were real musicians and wanting to be taken seriously. I actually really got back into it so much so that it really screwed my head for quite a long time because I had become a teenager again and I only wanted to talk about stupid things and my music so I must have bored everyone shitless. I have kinda of got a bit of a handle on it now, I can still switch into teenage mode but I can switch out of it as well and become a moany old git quite easily now as well. It was a great time, a very exciting time I gotta say, it was like an awakening, you know, it’s something that stirs something inside of you. But, you know, hearing Tom talk about his Life Of Angels, his deep sensitivity and feeling….is in total contrast to me, I must say I’m a total philistine, I’ve got no culture whatsoever, I just like sounds and I like playing with words. I like words that oppose like “sit down and stand up for yourself”, that type of thing. I like playing around with words that mess with your mind so… I’m not a great artist and there’s no poetry in my mind, my words don’t really mean a great deal…

Tom: You’re talking bollocks. (Giggling)

Pete: That’s what I do. I talk bollocks.

Tom: What a load of bollocks.

Pete: It’s just fun. I just like it. I just like the sound.

Jennifer [Tom’s partner]: Can I just interject here? Best riffs I’ve ever heard.

Tom: Yeah. Jennifer thinks you’re the best riffy guitarist on the planet. Your solos are amazing and, not only that, you couldn’t write words like you’ve written, like the lyrics that you’ve written for the Resurrection album without having a soul. You’re trying to make out that you’re some kind of Farmer Giles character. But you’re not a Farmer… you know you’re very spiritual, actually, you just keep it to yourself. You like everyone to think that you’re this big butch chappie but actually you’re a sensitive soul at heart. And nothing you ever say to me is going to persuade me otherwise.

Pete: Maybe, nice words. One thing I don’t write about, although I have in a weird way, is love and hugs and kisses and everything’s wonderful ’cause I’ve got a fairly black look on life, I’ve got to say, I think life’s something you get through, it’s pretty shit and you’ve kind of got to get through as best you can, I don’t sit easily with all… Having said that, I have a great family and in a grumpy sort of way I have a good life, so I’m probably a bit of a hypocrite. So the songs I write can be a bit weird because they can be very depressive, if you like. I suppose a lot of them are about being misunderstood and lonely, all the things that I probably brought forward with me from my youth, you know as a 17-year old I was, in my mind, misunderstood. I was frustrated and I was kinda lonely probably because I was an arsehole and as you know, we arseholes tend to be lonely. People hang around you for what they can get…

Tom: You were the original punk I reckon. (Pete chuckles) You wound everyone up because you looked like an angel and you acted like a devil. You were a right fucking pain in the arse actually. (Pete chuckles again) I remember Dennis Patterson, the priest down at the community centre, he banned you from everywhere.

Pete: I was unfairly judged though. (Roars with laughter) I was misunderstood. (Both crack up) I like the songs I write, I enjoy the words, I enjoy the sounds yeah, it’s kind of cool, and A Day To Remember is exactly that sort of skull fuck, you know where people say, “What are you talking about?” It is living for the moment, just not caring about anything at all, right at that moment is perfect, anything that went before gets forgotten, looking forward to the next moment tomorrow and then tomorrow becomes today and what happened yesterday has been and done and gone, finished.

Tom: The thing is, if Johnny Lydon, if the Sex Pistols had had the brains that you’ve got, that would have been a monster hit for the Sex Pistols, in fact it still probably could be. I might send it to Glenn Matlock and see if he wants it.

Pete: I’ve gotta say, Tom does a brilliant job on the vocals on it because when I first wrote it, it I called my hippie song. It was kind of very much love and peace style without the love and peace words, like hippies sitting around the campfire. What Tom has done with the vocals is was absolutely brilliant, he has captured what it is all about and given it a uncouth edge…

Tom: You gave me this kind of pep talk Ned, that’s what made it work. I only had your demo to listen to and it wasn’t hacking it, but once you got me into the idea and told me what the song was meant to be saying, ’cause I didn’t get it, it was too subtle for me. Once I got it, it was a piece of cake. I love that song. It’s great.

Pete: I do. I do.

Tom, tell me about Robert Reed. He seems be influenced by Mike Oldfield. I think you’ve produced his material?

Tom: Yeah, yeah. Well Robert, I only met him on Tuesday, properly. I mean I’ve met him once before, even though I produced the first Sanctuary album for him, we’d never actually met when I did the album. He just sent me the demo, and it impressed me. I’ve heard a lot of, Mike Oldfield – what I would call afficionados – who’ve, become fascinated and entranced by Mike’s style and the emotion that Michael puts into it and they’ve developed a style around that, but it seems to me that 90 per cent of them seem to living vicariously through Michael, they’re not actually saying anything of their own and they’re not expressing their own fears or emotions or feelings in any way. When I listened to Robert’s demo it touched me slightly in the same way that Michael’s first demo touched me way back in 1970 and I became interested in it because of that and it had a kind of a potential completeness to it. It was nicely constructed, even though it was actually constructed quite wrongly in places, which I managed to get him to put right. I mean some of the best hooks didn’t get developed, he would play a lovely little hook but only play it once and then forget it and go on to something else. With my producer’s hat on I managed to recognize some of those hooks and get him to expand the, in fact I actually expanded them myself and did a demo and sent it back to him with… constructed in a way that I felt would work better and he got into it. That was on Sanctuary I (one) and it worked very well and then, on Sanctuary II he sent me all the stems of the entire album and I did the same thing on that really. And it was the same problem, he would write a hook and then not have the full confidence in it to develop it. And also, to be fair, what he was doing as I found out when I talked to him on Tuesday, that he had a modern pop song producer’s hat on when he was writing it and he had the idea that – which is unfortunately true – young people tend not to be able to concentrate on anything for more than about four bars at a time thanks to the likes of Simon Cowell and the disco revolution, everything’s got to happen very quickly. But the thing that I think that he was trying to capture, the bit that he was taking from Mike Oldfield’s template of, prog rock work was that you can, if you construct it correctly, you can seduce people to sit down, put a pair of headphones on, throw the children into a cupboard under the stairs and shut them up, and listen to a record right the way through without looking at your i-phone or watching the telly, you know. And that’s what Michael was aiming for and that I picked up and made it work, but the prog rock movement has never done that again really. I suppose there are some bands that try to do a lot, you know, Yes and King Crimson and the Floyd. The Floyd are the perfect example, obviously, of where that’s happened, they’re the only other band, really, that do it 100 percent. And so I recognized that in Rob’s stuff and the reason I really like it is because I can see him as being the most recent, and maybe the only person at the moment who’s extending the life of prog rock in a way that Michael has dropped out of.

Michael’s now writing crappy songs and getting other people to sing ’em. You know, I mean, Luke Spiller’s great, you know, the album’s OK but it’s not what he’s supposed to be doing and I think Michael’s forgotten what he’s supposed to be doing. I dunno if he’s maybe getting a bit too old, it’ll be interesting to find out. At least in Rob Reed he’s got someone who’s taking the baton, if you like, and carrying on the race really, in the sense of what listening to music is about, it’s listening to music not using it as a TV ad or a distraction or a bit of wallpaper or something that you look at on your i-phone. I think it’s a terrible thing that the digital revolution has put music into Spotify and fucking i-Tunes, it’s made it cheap and it’s completely devalued it. Even something like the new July, Resurrection, it’s brilliant if you take the trouble to sit down and listen to it, it’s really rewarding and yet people just don’t do that, you know. If they don’t get some kind of bizarre satisfaction out of the first 15 seconds of any piece of music, then they change channels or they look on their iPhones and see who’s on fucking Twitter. The world’s gone into a state of I don’t know, wierdness, and the thing I like about Rob – sorry, I’ve been blathering on – is that he’s hopefully helping to balance that out a bit in the same way that I am with things like, The Secret Life Of Angels, and I’ve got several other albums kind of cooking in that area at the moment and, you know, I think music should be listened to in the time honoured way, ‘Put your headphones on, lie down on the floor on a cushion, smoke a joint or have a brand, lie back and let the world drop away from you and listen and get into the music.’ That’s the way it should be. I mean, when I first designed the Virgin Record shops, that’s exactly why we put big cushions all round the floor and gave people headphones, to let them chill out and that was part of the design philosophy of the creation of the whole Virgin idea really. Anyway, that’s me. Sorry about that, I’m blathering along again, I lost the plot, I can’t even remember the question. Sorry, Jason.

That’s all right. I’m gonna get my bean-bag, I’m gonna lay back, (Tom chuckles) I’m gonna relax, I’m gonna get my brandy and possibly some illegal substances and listen to Rob Reed’s Marimba.

Tom: I never encouraged you. That’s nothing to do with me. (Both laugh)

You released – Can I Go Back Again – on the Fruits de label. That’s a really nice single. I’d like to go there into the sixties, but you guys were actually there. Lots of Beatles references, which are pretty cool. Was that one of yours Peter?

Peter: Yeah, yeah. It’s a bit of fun. It’s nostalgic fun ready because all the words are from Beatles songs apart from a couple that introduce it, so the whole thing was constructed solely from Beatles songs, so I just hope I don’t get Mr McCartney or anyone come around knocking at my door asking for some of the proceeds. They wouldn’t get a lot but I mean they might. Thinking about it they’re welcome to knock on my door, Please Mr McCartney come and knock at my door, that was good fun but…

Tom: Knock at my door*. I think that’s from a Beatles song as well.

(* Tom is recalling the Paul McCartney penned Wings song “Let ’Em In”)

Pete: Well, there you go. You can’t help it can you? The Beatles are just phenomenal. They’re just such a massive influence and it was such an exciting time. That era, I can’t believe that youngsters today, I sound like an old git by saying youngsters today, but I can’t believe that they will ever be able to experience what we experienced at that time because it was so completely different. Now everything is just a mishmash and a melting pot of everything and it’s just something else that’s a progression from what’s gone before or rehashing it. Then, it was so different, it was so exciting, when I say “Can I go back again”, I’d love to. I’d love to feel that excitement again as a youngster with all that’s going on, you’re full of hope, everything is possible, you’ve got great aspirations. As you get older you realise that fuck all is possible and that your aspirations come to shit, but when you’re young, it’s just a wonderful time, you’re so naïve, and it’s just great, you’ve got no cares and no worries. It was just fun putting the song together and I think we achieved what we wanted to, to give it a modern feel but with our ’68 heads on gwith references to the sixties. It’s a nice tune that goes on. It’s got one of those endings that could’ve gone on and on and on and on and on and on but people would’ve probably turned it off before it got to the very end if it had gone on any longer. I think it’s a nice floaty song and, I enjoyed making it happen.

Tom: Brilliant Ned.

I think it’s sold out already.

Pete: Well, yeah. The original run was in red vinyl and they all sold out, so there are a few black vinyl versions available I think. That’s incredible. Having a run, that’s unheard of, producing something and it’s selling out just like that you know, absolutely amazing. It’s going back to what Tom was saying earlier about playing to audiences who know your songs and appreciate it, It’s priceless. Where else can you get that reward from other people, particularly youngsters who would normally see you as an old git, youngsters actually appreciating what you’re doing and liking it and clapping you and wanting more, that’s priceless, that’s wonderful. What a good way to go out actually, perhaps that what I would like, people clapping as I go down… slide down into the old crematorium at the end. That would be nice.

What’s next? More live shows? Any more new music in the pipeline or anything?

Tom and Pete (in unison): Well.

Pete: Yeah. Carry on Ned.

Tom: I’m moving to the Isle of Wight soon, I’m getting out of London and leaving Northern Ireland, I’ve been commuting between London and Northern Ireland for a long time so the Isle of Wight will put me a lot closer to the action. One of the things I really want to do is another July album. Also, and I don’t know whether we’ll ever be fit enough and (laughs) or have enough brain cells left but I really enjoy live gigs. The disappointing thing is it’s always nearly impossible to be able to do live gigs without having to end up paying in some way. Just to make them pay enough just so that you’re not dipping into your pension in order to do the gig has been difficult. I mean we’ve had occasional gigs where it’s been very generous and we’ve all walked away with a few bob in our pockets but then you get a bunch of gigs that you want to do because they’re really interesting gigs, but nobody’s got any money so you end up, you know, robbing Peter to pay Paul. So, coming out level is a real problem, and because the material’s complex we can’t do it without a bunch of rehearsals. Poor old Pete tends to pay for the rehearsals ’cause I ain’t got no money so it’s not easy but I would still love to carry on doing live gigs. I mean the ideal thing would be to be picked up by some monster-sized, world-sized band and put on a world tour with them, that way we could get through to a few more people. One of problems is though that we’re so fucking good on stage that, even if we were on tour with the Rolling Stones, we’d kick ’em into a cocked hat and they would chuck us off the tour because we’re actually better. So, you know, we’re very exciting and a very good band live and the material is a lot more interesting than the Stones, really, I mean, come on. You know, Mick, he’s a kind of a parody of himself now and it’s almost sad. Although we’re the same age, Mick and I are pretty well the same age, within a few months, I’m ever so glad that I’m in July and not the Stones (laughs raucously). I mean I don’t mean that Mick. I do mean it…a bit.

Pete: In the best possible taste.

Tom: In the best possible taste (continues laughing). No, what I like about July is that we’ve never been copied because we’ve never been up there, so we haven’t got that whole weight of early material that the Stones have got which confuses them because they don’t really know what they should be now. They’ve lost… They’re not writing any good song anymore, they’re not writing another Brown Sugar. I mean their best album was Sticky Fingers and they haven’t written anything since then, that was their Sgt Pepper, that was their July album, if you like, and everything they’ve done since then has been a lot worse than Sticky Finger,. I don’t know why. They haven’t got the fire in their belly anymore, probably because they’re too wealthy, whereas Pete and I haven’t got two ha’pennies to rub together so we still have got the fire in our bellies to write songs that actually come from the soul and from the heart, from where it was coming from in 1968, when we had young fire in our belly. But we’ve still got it now and I think, all we gotta do really is to get spotted, you know, by a Simon Cowell. You never know, he might get it but I doubt it though…. (more raucous laughter)

Pete: You’d have to learn to wiggle your bum I think to get on there.

Tom: We’d go down very well on Simon Cowell. Simon (he hollers). Give us a break mate!

So possibly a new album and some live shows.

Tom: Definitely, definitely another album. I don’t think a band like July should go out without having three albums in the catalogue. You know, a triumvirate. A three-part career is good, two albums doesn’t mean anything but three albums is the right number of albums to have, when you’ve been around for 60 years, an album every 20 years is a good idea.

Pete: So I guess the next one then is going to be about 15 years time.

Tom: Oh yeah. Yeah but, you know, the last one actually is already ten years old nearly.

Pete: Yeah. Yeah.

It’s been an education and a privilege to spend time with you guys. Such a great band with a great heritage and, you know, and recently referenced by Sean Lennon as, you know, the greatest underground psych band, so you’re still making waves now.

Tom: Thank you very much Jason, it’s been a pleasure.

Pete: Yeah. Ditto. Thanks Jason.

So here’s for a third podcast in another six years time…

Pete: (chuckling) Yeah, yeah. We’re on.

…with a new album.

Tom: Yeah, but hang on. I’m actually writing my memoirs so, you know, we could do a podcast about my memoirs in six months time. What about that?

Why not? Let’s do that Tom. Fantastic. Well, we’ll do that.

Tom: I’m looking for a publisher, if you know anyone.

OK. Cheers guys and thank you so much and have another glass of wine and over and out.

Pete: Over and out. Cheers Jason.

Bye.

Tom: Night Ned?

Pete: Yeah, ’night Ned.

Resurrection is out on Psychotron Records (PR 1005), in a limited edition of 500 worldwide. It is available through www.psychotronrecords.com, from mid November 2016. Price £18.

= = = = = = =

Other related articles:

An audio version of this interview with accompanying music tracks can be found here: http://thestrangebrew.co.uk/http:/thestrangebrew.co.uk/july-tom-newman-and-peter-cook/

Interview with the reformed July – 2010:- http://thestrangebrew.co.uk/articles/july-magical-days-part-1/

Exclusive interview with Tom Newman: The Tomcats & July chapter:- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mWNsQ8AQqRI

Photos of John Entwistle’s flame bass guitar:- http://www.whocollection.com/john’s_basses.htm

Various Fenderbird and Explorer-bird basses:- https://uk.pinterest.com/pin/348817933610176840/

Sanctuary II details:- http://tmr-web.co.uk/robreedsancturay/Blank.html