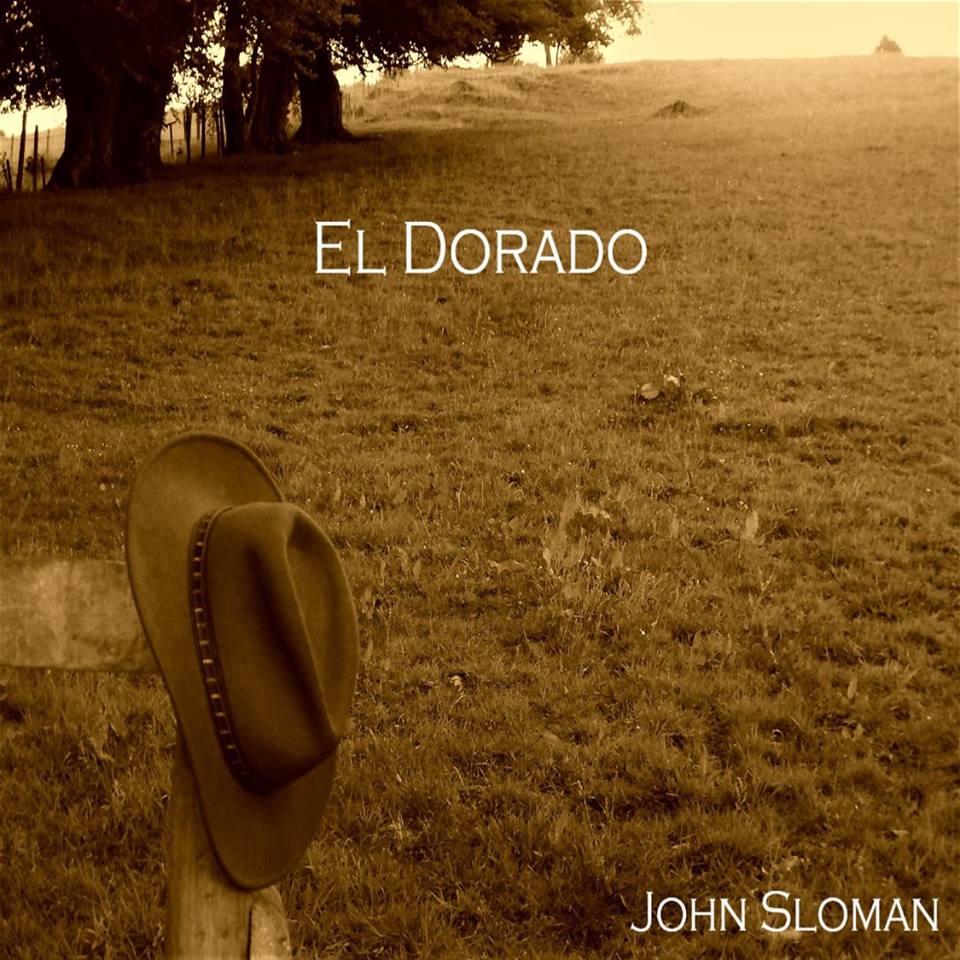

Hailing from Cardiff, South Wales, John Sloman is one of the great voices of the British rock scene and former frontman of Lone Star and Uriah Heep. John talks to Jason Barnard about his time with those groups, Gary Moore, Todd Rundgren, and solo work including his acclaimed new album ‘El Dorado’.

Hi John, thanks for taking the time to speak to me. I really enjoyed listening to ‘El Dorado’ so it’s great to see it receiving a CD release. Am I right to assume you’re responding to the demand from fans for something physical?

Thanks Jason, for taking the time to listen to El Dorado. I’m really glad you like it. The album was originally released as a download, like my two previous albums ‘Don’t Try This At Home’ & ‘Taff Trail Troubadour’. But, due to people showing a preference for a physical release, I decided to go for it. And of course, I prefer physical releases. After working hard on something, one likes to hold something in one’s hand as evidence of all one’s hard work, rather than what I call a ‘Digital Waft’.

‘El Dorado’ has a rootsy American feel typified by the title track and ‘Down To Memphis’. What inspired you to write and record this album?

The album was inspired by the death of my brother Robert. Rob was in hospital for eleven months. In spite of Rob having liver disease, and not being expected to survive without a new liver, he would often talk about what he was going to do when he “got out of hospital” One of these things he was going to do was buy a boat and go fishing off the South Wales coast. On hearing this, I went home to my little studio room and wrote him a song called ‘Jason & The Argonauts’ – casting his little fishing boat as the mythical Argo from the iconic 60’s movie (a song we’d both loved as kids) – and he and I as its crew. I wanted to lift him out of that bed with the power of music, hence the opening line: “Brother get out of that bed…” I played the track to Rob in his hospital room and he loved it. When Rob died eleven months later, I wanted to tell the story of his life in America – beginning with him leaving this country to start a new life in another country. I also wanted to reflect various aspects of the music of his adopted country: rock, blues, soul, country, as well as capture some of the flavour of some of Rob’s personal favourites such as Frank Zappa (Welshman).

‘I Love This Land’ is a showstopper. Which tracks from ‘El Dorado’ are your favourites and why?

‘I Love This Land’ is one of my favourites from the album. I think it captures Rob’s sense of optimism while at the same time accepting he might soon be leaving it all behind for good. ‘Down To Memphis’ is about a trip I took with my then 78 year-old mother to visit Rob and his wife. The four of us took a road-trip from Arkansas to Memphis, stopping off en route at a biker-rally on the Arkansas/Missouri border where I jammed through Black Magic Woman with a local band. On reaching Memphis, we took in Gracelands, Beale Street and Sun Studios where Rob tried to persuade me to record a blues album at Sun. Maybe I’ll still do that one day.

‘If I Live Through This Night’ is another reflection on Rob’s refusal to lie down and die, even when the only option left for him was to do just that. ‘Jason & The Argonauts’ is another favourite for the reasons I mentioned earlier. But also, because it’s the only track on the album that Rob actually heard. ‘El Dorado’ has a special place in my heart, as it’s about the time I flew to USA to bring Rob home before he became too sick to fly. The two weeks spent at Rob’s place, helping him wind up his affairs, were some of the most intense times I ever knew, with the howl of the train as it thundered through town several times a day articulating all my deepest fears that Rob would die before I got him onto a plane. I believe this song is the rawest emotionally, as it was written within weeks of Rob’s passing.

Where did do you record the album – was it a quick process?

The album was recorded at home in the same little room I’ve recorded all my albums since 2000 when I finally got myself a decent recording set-up. Hard to say how long the album took in totality to record because I was taking breaks whenever it got too much; but I started writing the songs around March 2016 – and I finished the final mixes around March this year.

Who did you record with or was it a mainly solo affair?

I performed, produced and mixed the whole thing alone, using the same methods I’ve used on everything I’ve done in the past twenty years. I have no budget whatsoever, so have to improvise around what I don’t have to hand. I call it Robinson Crusoe Recording – you’re completely alone and you use whatever washes up on the beach on any given day. A couple of years back, a glockenspiel and a xylophone washed up, and I incorporated both into some of the tracks on ‘El Dorado’.

Going back, can you tell me about growing up, your background and how/if this influences you?

I grew up around a lot of music. My grandmother taught me lots of old vaudeville tunes, and by the time I was seven I was performing Al Jolson songs in front of audiences of pensioners up and down the Welsh Valleys as part of this singing and dancing school. My vaudeville career lasted about three years. Meanwhile, my cousin David played bass with Shakin’ Stevens – not the 80s version – but the 60s version. He lived with us for a while and my ten year-old self always felt a shock of excitement go through me whenever I saw David’s Fender Precision bass propped against the wall in the front-room. My dad loved Mario Lanza. I’m sure some of those operatic cadences found their way onto some of my earlier recordings. Both my parents loved Rogers & Hammerstein and Leonard Bernstein, and the soundtracks from movies such as ‘Sound of Music’ & ‘West Side Story’ would often fill the house. Also, both my parents had good singing voices, and they’d often be heard duetting on some old love song from their courting days. Meanwhile, just beyond the walls of the family home, the city of Cardiff, due to its long history as a sea-port, was buzzing with new music from all corners of the world: Rock n’ Roll, Blues, Reggae, Soul, Ska. Good music was everywhere, so if you had a band, however young, you were expected to be good.

You first came to prominence with the band Lone Star in 1977. Do you think if the band had released its material after the punk scene died down it would have had more commercial success?

Lone Star arrived on the scene at exactly the wrong time. I talked to Tony Smith a while back, and he was saying that the band should’ve moved out to USA where we might’ve found an audience. It was troubling watching the whole music-biz re-engineer itself seemingly overnight, and people who were in our corner last week now calling us “boring old farts” (I was 20 at the time!)

Can you tell me what joining Uriah Heep was like in 1979, given they were an established group. Did you have much influence over the music on the album ‘Conquest’?

Uriah Heep is a complicated story (might need a few extra sheets of A4 for this one). I’ll give you the abridged version and save the full-length version for the book I’ll be releasing in the new year:

I’d spent the summer of ’79 in Canada in a band with Dixie Lee & Pino Palladino. I returned to UK that September to discover Uriah Heep had been trying to contact me. I did an audition – Trevor Bolder was keen on getting in me into the band – he’d watched Lone Star’s set at Reading Festival ’77 from the side of the stage and was impressed, so when Heep needed a vocalist, he suggested ‘that kid from Lone Star.’ Unfortunately, Ken wasn’t keen at all. And he wasn’t the only one. I did another audition. When the band still couldn’t come to an agreement, I called Trevor and told him I didn’t want to jump through any more hoops and I was going back to Canada. Within an hour, Trevor had called around the band and called me back to say I was in the band. Of course I already knew Heep’s music. I had some of their albums and most of my friends were Heep fans. But it wasn’t pleasant being in a band, the main writer for which, didn’t want you there at all. As a result, I had to watch my back (constantly). I won’t go into more detail here, but suffice it to say, my cautious attitude was entirely justified by events which occurred in the first few months of my being in the band.

Uriah Heep, 1980 (Left to right: Chris Slade, John, Trevor Bolder, Gregg Dechert, Mick Box) (from Uriah Heep website)

Did I have much influence over the music on Conquest? Well, I contributed two songs – ‘No Return’ & ‘Won’t Have To Wait Too Long’. Other than that, the album was 70% finished before I joined the band. Ken added one more track ‘Out on the Streets’ to complete the album. When I left the band, they tried to put the entire blame for Conquest not sounding like Heep on me. But as I said earlier, the album was 70% complete before I joined. I understand it was just business at the time, and they were in a process of re-launching after I’d gone, so they probably thought ‘Hey, let’s blame that guy!’ The first thing I thought when I heard the backing tracks for Conquest (before I did anything at all on it) was ‘this is different’ to the early stuff’. For a start, Ken was using an Oberheim polyphonic synth. I’m surprised they didn’t try to blame me for that (ha!) Listen to ‘Out on the Streets’ – sounds nothing like Uriah Heep – and it was written by the same guy who wrote all their career-defining material. Go figure. In spite of all this, I became close friends with Trevor, Mick and Chris – and of course Gregg when he eventually joined the band after Ken’s departure.

So why did you leave Uriah Heep and how did you get to join Gary Moore’s band?

There were many other factors which led to my leaving Heep. But the main reason was that I wanted to do my own thing – and I couldn’t do that as well as be in Uriah Heep. It was the right thing to do – but it cost me a lot. Trevor was the first one I told. He seemed to understand my reasons, but I knew that he took it personally. After all, he’d busted a gut to get me into the band. I always hoped to catch up with Trevor at some point, so when I heard that he was seriously ill, I sent him a message. When I didn’t get a reply, I put it down to him having more important things to concern himself with. Meanwhile, the word around the Heep site was that Trevor was returning to the band for gigs following his treatment. When I heard Trevor had died, I was shocked. It was only then that I learned that he’d had pancreatic cancer, which is one of the most virulent strains of the disease. The Gary Moore thing came through Neil Murray. Right from the off it didn’t feel right. Gary was amazing of course. And so were the rest of the band. But I was fronting someone else’s band again – singing someone else’s songs. Then I got ill – and stayed that way for the duration of my time in the band.

What are your memories of recording ‘Corridors of Power’?

I didn’t actually work on Corridors of Power. But I was on the live album recorded in Japan.

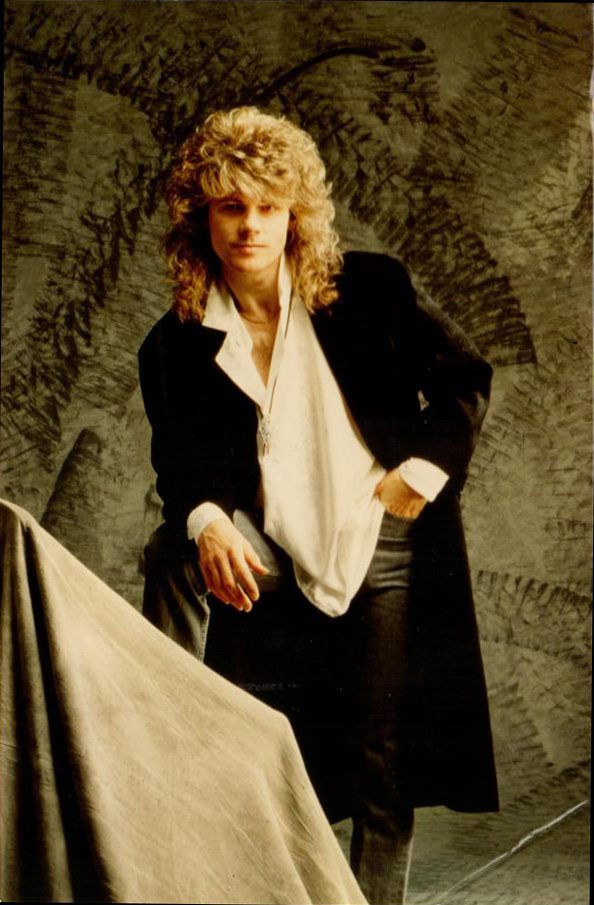

John, 1989 (from Revolver Records)

Todd Rundgren produced your album ‘Disappearances Can Be Deceptive’. I spoke to Colin Moulding of XTC about working with Todd and it was clear he has a reputation of being producer who has a clear view of what he wants. What was your experience of working with him?

Todd Rundgren produced the original sessions that took place at his studio in Woodstock. The label then rejected those recordings and the album was reworked with Simon Hannhart at a studio in London only for the album to be shelved. The disappointment stayed with me for many years. I couldn’t talk about it, which did me a lot of psychological damage, nor could I listen to Todd’s music, which I loved. Meanwhile, those around me knew not to even mention Todd’s name. Then there were the musicians who I ran into around town: “Oh John – why didn’t you talk to me? I could’ve told you all about Todd Rundgren!” Or: “Didn’t you hear about what happened with XTC?” It was a monumental head-fuck. Looking back all these years later, I recall on the first day, Todd presenting me with a written critique of my songs – which unnerved me somewhat – like getting a bad report from your favourite teacher. And he could be a little antagonistic with the musicians I’d brought with me from London, constantly referring to them as, “Frustrated jazz musicians!”

But this was Todd Rundgren – he was one of my all-time favourite artists – he had to be good somewhere. And sure enough, during the tracking stage, he was especially so – most notably during the recording of ‘Fooling Myself’. And of course, he was great with vocals. Todd and I did the backing vocals together. And it was an honour to share a microphone with him. Unfortunately, those original recordings have long disappeared, along with Todd and I’s bvs. Truth was, I wanted the Todd of ‘Initiation’ & ‘War Babies’. But instead I got a better-produced version of my original demo-recordings. If I had that time over again, I’d insist on recording some of my more unusual songs – like ‘The Other Side of Love’ – which would eventually see light of day several decades later on an album I did called ‘Reclamation’. In spite of all the above, my respect for Todd as an artist, remains undiminished.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PCc3OSLOVfE

In the 1990s you were part of a range of projects but did not release another solo record until 2003’s ‘Dark Matter’. What are your highlights from that period?

I spent a large part of the 90s getting over the 80s. But I was always writing and recording new material. I briefly formed a band with Pino Palladino, Steve Boltz and John Munro called ‘Souls Unknown’. Meanwhile, Pino and I were writing material for our own project. I also recorded an entire album in a studio in Newcastle, featuring Pino and John Munro. It was very dark and heavy. I have recordings of all this unreleased material stashed away in my cupboard along with all the released stuff. I also recorded more or less an album at a friend’s studio in Wales. Jeff Beck heard one of the tracks (Jammin’ with Jesus) and wanted to cover it. There was this phone call where first I talked to Jeff who was in the studio in the process of recording my song – Jeff then passed the phone on to Steve Lukather, who was producing the session. I thought ‘who’s going to be next on the line – Henry Kissinger?’

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7hk7vJK0gv0

‘Dark Matter’ was the culmination of this whole period – I took the best of the material I had – some of which I’d recorded before – and recorded the whole thing with bass-player Jonathan Thomas & drummer Steve Wyndham, over a period of three weeks in rural Wales. A label had originally been involved – but they’d pulled out the day before we were due to start. But thanks to the studio owners John Payne & Geoff Downes, the recording went ahead anyway, and turned out to be a very enjoyable experience, in spite of all the false-starts and disappointments I’d encountered along the way.

You’re more prolific now than ever, releasing albums ‘Don’t Try This At Home’ and ‘The Taff Trail Troubadour’ in recent years. Do you have a backlog of material to draw from or are these newly written tracks?

I read something a while back saying that I was “really good – but not very prolific.” It really got to me. Truth is, with the exception of a couple of years following the Todd thing, I’ve always been prolific. It’s just that I haven’t been able to get my stuff released. These days, you just put it on the net. But all through the 90s especially, I was still trying to get label interest. But due to the fact that I didn’t want to just churn out yet another typical classic-rock album, labels would initially show interest, then run away. Meanwhile, all that was out there were Lone Star, Heep and Gary Moore albums. It was frustrating to have all this new material and no way of releasing it. Then, 20 years ago, I got my home set-up. And suddenly, my output reflected my level of creativity. The first album I released of this new era, was an acoustic album called ’13 Storeys’. Then came ‘Dark Matter’. I then released another acoustic album called ‘Reclamation’. I followed up with ‘Don’t Try This At Home’ – ‘The Taff Trail Troubadour’ & ‘El Dorado’. I always have a back-log of material. But every new album (especially The Taff Trail Troubadour & El Dorado) is mostly new material.

Out of all of all the material you’ve been involved with, which LPs and songs are you most proud of?

Stuff I’m most proud of? From the Old Testament of my so-called career, I’d say ‘The Bells of Berlin’ was pretty good. ‘No Return’ from Conquest. From the New Testament: as an album -‘13 Storeys’ (I taught myself basic violin and cello for the string parts) – ‘The Other Side of Love’ & ‘Hope’ from the album ‘Reclamation’. I think ‘Dark Matter’ hangs together pretty well. ‘Don’t Try This At Home’ as an album – because it was such a nightmare to do – chopping up my couch to make room for the drum-kit etc. It was more like mountain-climbing than making an album. Luckily, I’m used to doing things the hard way. I like ‘The Hunt For Dawkins’ from ‘The Taff Trail Troubadour’, because it’s so different to anything I’d done before – and a different universe to my Old Testament career. The title track from ‘El Dorado’ always moves me, as it does those who I play it to at gigs.

What are your plans as we go into 2019 – live shows/collaborations?

2019 will be my most productive year to date, beginning with a CD release of ‘El Dorado’. Later in the year, I’ll release the album I was working on before my brother Robert’s death prompted me to change my plans. Before the end of the year, I’ll release the follow-up to ‘The Taff Trail Troubadour’ titled ‘The Taff Trail Troubadour Rides Again’, featuring another bunch of songs written from the ‘wrong side of the bed’ – the TTT once more holding a mirror up to the world and then smashing it to pieces! I’ll be doing the usual solo acoustic gigs – and who knows – maybe some with a band? 2019 will also see the release of my book which tells the story of all the people I rubbed shoulders with at the grindstone of rock – as well as making the kind of commentary one might expect from an aging rock musician who has seen through the bullshit on planet earth and can remain silent no more. My intention is to put a solo show around the book – telling stories – reading passages – playing songs from whatever period in my so-called career I happen to be talking about at the time.

It’s a pleasure sharing your story, John. All the best for 2019 – Jason

‘El Dorado’ is released on CD on 4 February 2019 on Slogger Records:

- Hear it here and or purchase the download: https://store.cdbaby.com/artist/JohnSloman

- To purchase the CD: https://johnslomanmusic.bigcartel.com/products

Also available:

- 2017: ‘The Taff Trail Troubadour’ from: cdbaby, Amazon & iTunes

- 2016: ‘Don’t Try This At Home’ free download from www.johnsloman.net