In an exclusive extract from There Was A Light, a new biography of Chris Bell and the rise of Big Star, Rich Tupica shares revised and updated interviews with Chris and those closest to the group. This chapter delves into a pivotal time for Big Star, their formation in winter 1970-1971.

By December 1970, Chris and Steve decided to shop their three-song Icewater demo tape to major labels in New York. While they knew landing a deal was a long shot, Chris’ entire crew flew to the East Coast with high hopes, only to be labeled as “Beatles wannabes” by an Elektra Records representative. A few other meetings went nowhere, though the fateful trip served a higher purpose after Chris reunited over acoustic guitars with his old friend Alex Chilton, who lived in the Village.

Steve Rhea: Icewater played one dance in Memphis and then caught a plane the next morning to New York. We took that tape to Elektra Records and some other companies.

John Fry: Alex Chilton had been up in New York for some time. They knew Alex was up there and went to some lengths to seek him out.

Chris Bell: As a reaction to quitting the Box Tops, Alex went to New York to get away from it all and started hanging out in Greenwich Village. He was doing the folk scene with people like Loudon Wainwright III. He went to New York and stayed there for a year and met up with Keith Sykes.

Steve Rhea: Chris stayed at Alex’s apartment. Jody, Dando, myself and Andy all stayed at this hotel in Times Square. We were trying to see if anyone would release our songs or give us a budget to go back into the studio and keep pursuing this original material. We didn’t get any takers, but we did sort of hook up with Alex at that point.

Robert Gordon: Chris met Alex in New York. They quickly realized they had a Lennon/McCartney kind of pairing and they wanted to further explore that.

Chris Bell: [Alex] talked to me about going to New York with him to do a duo thing, I would play electric guitar and he would play acoustic, like Simon & Garfunkel, or something. He’d been into the acoustic scene and I had been in an electric scene and I didn’t want to leave my band…I was none too keen despite his persistence.

John Fry: Chris ultimately approached Alex with the idea of returning to Memphis and joining this band that eventually became Big Star.

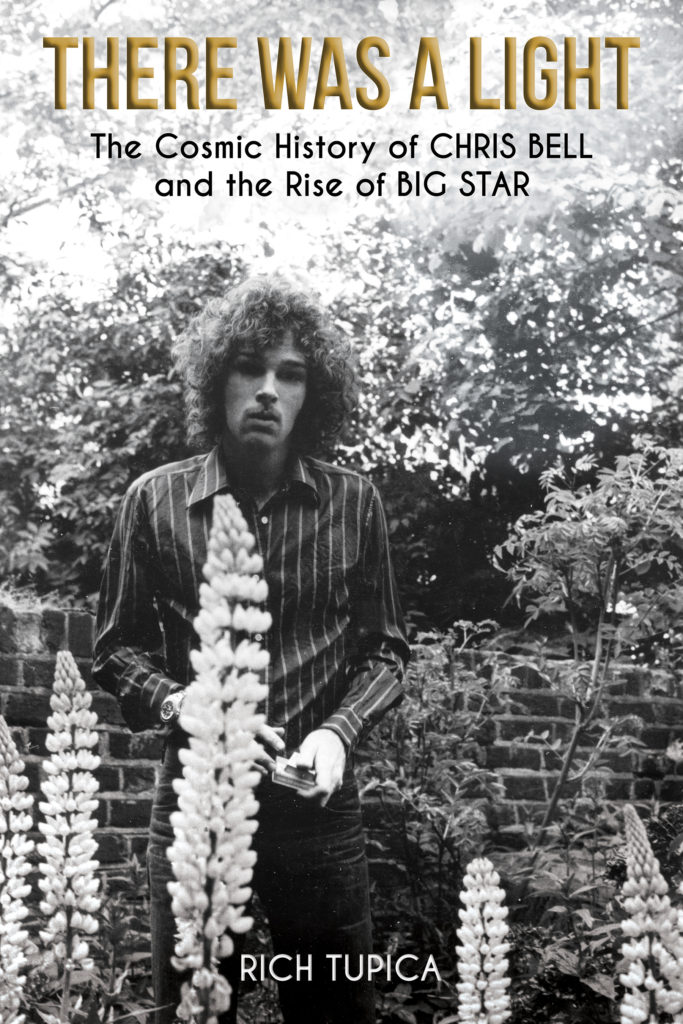

Chris Bell (photo used under creative commons)

Having made a loose agreement to catch up and collaborate soon, Alex promised to check out one of Icewater’s shows on his next visit home to Memphis. He wasn’t ready to abandon New York. With his girlfriend Vera Ellis by his side, Alex crashed at two different apartments on Thompson Street, pads leased by his close friends Keith Sykes and Gordon Alexander. He also befriended an assortment of musicians, and crossed paths with rock critics like Rolling Stone’s Lenny Kaye and Bud Scoppa. One night at Bud’s apartment, Alex mingled with his idol Roger McGuinn. He and Vera also attended Vietnam War protests, and were seen at folk, jazz and rock clubs like the Gaslight and Max’s Kansas City. More importantly, Alex started performing solo at small clubs.

Alex Chilton: I would play around occasionally with an acoustic guitar. Hang around and play and learn. I knew a lot of folk musicians and was sort of interested in that kind of music, too. But [New York] was happening before that. By the time I got there it wasn’t like it was in 1967 or earlier. Sixty-four would have been neat.

Chris Bell: He was starting to pick up some acoustic licks, just learning how to play country music and what was going on in New York at the time.

Alex Chilton: There were still a lot of bluegrass musicians who would come and hang out in Washington Square every Sunday. I fell in with a mandolin player down there and we were good buddies. His name is Grant Weisbrot.

Keith Sykes — Singer-songwriter, guitarist, solo: Alex and I listened to a lot of music and visited record stores quite a bit. He turned me on to Aaron Copland. He also explained electric guitars to me, told me which ones made what sounds. He was a cool cat.

Vera Ellis: He didn’t come out of the Box Tops with much money, but he also was giving his ex Suzi and their son Timothee a big chunk of money. We had no money when we lived in New York. Occasionally, we would go down to the strip to Max’s Kansas City to hang out. We never went out to dinner or anything like that. Mostly, Keith and Alex just sat around and played music.

Alex Chilton: I wanted to get to the point of playing to where I didn’t need a band. I wanted to be able to go to a town anytime I wanted with a guitar in my hand and go into a club and get a job.

Robert Gordon: Keith Sykes, who had a record on Vanguard, was in New York doing the folk thing. Alex was staying on Keith’s couch. That’s where Chris met him, at Sykes’s apartment in New York. Alex wanted to play guitar, he was becoming good at it. He was writing songs, it was post-Box Tops and folk seemed like the way to go.

Alex Chilton: I was confused. I didn’t have a style. It was trying to evolve. I had always liked Dylan a lot. I had just quit the Box Tops, so I figured that I may as well make it so I could play all by myself. I didn’t need anybody else. I thought I would live in New York and that would be fun, but I didn’t play much while I was there. I was so scared and nervous that my hands would tremble too bad to play. I played the Bitter End, the Gaslight, maybe some other places. I learned a lot of bluegrass songs and a lot of those ’60s folky things. My writing was evolving. “Thirteen” came from that period.

In preparation for his impending collaboration with Alex, Chris started of 1971 with his next studio-project, Rock City. He wanted to be equipped and organized by the time Alex returned to Memphis and this served as his trial run.

With Steve Rhea away at college, Chris tapped his childhood friend Thomas Dean Eubanks to join the sessions. The songwriting partnership led to the creation of “My Life is Right” and the optimistically melancholy track “Try Again,” both later used on #1 Record. Paired with Chris’ contributions is a stockpile of Tom’s solid rockers like “The Preacher,” “I Lost A Love,” and “Think It’s Time to Say Goodbye.” Alongside them was Terry Manning, who contributed production work, keys and backing vocals. Jody Stephens stepped in on drums. Fellow Memphis-based musician Randy Copeland contributed basslines on multiple tracks. Rock City never played a live show, but served a higher purpose as it laid the sonic foundation for Big Star.

Steve Rhea: I didn’t have a high confidence level [as the vocalist in Icewater]. Maybe that influenced Chris to engage Tom Eubanks or Chilton and try and come up with a band that could actually get people’s attention.

Tom Eubanks: Chris called me up and said, “Do you have any original songs?” I said, “Actually, I do have a few I’m working on.” He said, “Well, I need to learn how to use the recording equipment for this project I have coming up with Alex Chilton in a few months, would you want to record them? You can use the studio for free.” Chris took me over to Ardent and I got to know John Fry and Terry Manning. It turned out that people liked the songs and that’s when Terry got involved.

Terry Manning: Tom Eubanks came in and he had some pretty good songs, he sang and played bass. Chris, Tom and I started putting those songs together and it just sort of morphed into a studio band. Jody played on most of that, we just sort of made a group. Rock City was our first attempt at an actual group album by the backhouse gang.

Tom Eubanks: When we went in the studio, the songs just happened to come together. A lot of that is just luck and faith, but Chris could bring something to the table that just fit right. Terry Manning added little touches to tunes.

Terry Manning: Chris and I tracked most of it and I mixed it.

Tom Eubanks: Jody, once he did his drum parts, was gone because he was just kind enough to play for free. It was the first time he ever recorded…I already had “Lovely Lady” and “Think It’s Time to Say Goodbye,” which would have come across as more Kinks, if Chris hadn’t put so much slapback echo on the guitars. Chris played bass on both of those.

John Fry: These earlier projects, like Icewater or Rock City, I had little to do with. They were proceeding on their own. It does seem paradoxical that we had all this highly organized structure, and then this other activity that was unstructured, but a lot of that comes from the home-studio days.

Tom Eubanks: We always cut in the B Studio, that’s where Chris liked to record. John Dando would set up all the equipment, we would play, and then Dando would tear it down. We would go in at 11 p.m. and stay until 3 or 4 a.m., even when I had to be to work at 7 a.m.

Priming his engineering chops wasn’t the only perk of these sessions for Chris, he also explored his lead-vocal range on “My Life is Right.”

Tom Eubanks: I wrote all the words and then I went over to Chris’ parents’ house and sat on his bed in his bedroom. I showed Chris the lyrics and he said, “Yeah, I can do something with this.” When it came time to sing it, Chris sang it back to me and when he got to the chorus and sang, “You are my life, you are my daaay,” he went up to a part a high-harmony guy would sing. I told Chris, “I can’t sing it, man. You sing it.” I think that had something to do with Chris starting to sing lead on records. I said, “This is turning into more of a group thing, anyway, rather than a record on me.”

Having the skillful Terry Manning on hand added some further technical fare to the Rock City tracks, including a makeshift “string section.”

Tom Eubanks: We needed string sounds on “The Preacher,” but had no money for strings. Terry was doing a string session and got them to record single notes and taped them on the eight-track. For whatever reason, they had an orchestra at Ardent, either for a jingle or a session for Stax. He got different notes and would bring them up on different faders and then operate the faders to make chords, making a string session. That was the dynamic of the Mellotron. Terry used the faders to play the notes. It was absolutely brilliant. I had all the words for “The Preacher.” I gave them to Chris and he wrote the music. Even though it’s a Beatles-esque lead, that’s one of Chris’ best lead guitar parts of all time.

Terry Manning: It was Chris who decided to call it Rock City. Down here you see signs that say “Rock City” everywhere, advertising the attraction near Chattanooga where you go up and see the rocks. Their motto was “See Seven States from Rock City,” Chris thought See Seven States could have been the title. It was a pretty good idea, but when I finally released it [in 2003 via Lucky Seven Records], I didn’t end up going with that idea.

Tom Eubanks: After we finished the songs, I was given about twenty quarter-inch tapes of the album and a list of contacts of major record labels. I went about my way cold-mailing the material out; the thing is just a glorified demo. The only label that gave it consideration was A&M. Somebody from there was interested in it, but since it was something they’d received cold in the mail, nothing ever happened with it.

Terry Manning: A funny thing was, I mixed up the mixed tapes inside the wrong boxes, and the Rock City mixes were lost and forgotten for years. I had put them in a box labeled “Tom and the Turtles” and didn’t fnd it until the late ’90s.

Tom Eubanks: Back when we were recording, on one of the boxes for the eight-track we recorded on, I wrote “Tom and the Turtles” on it—just to be stupid. Chris wrote “Rock City” on the other one.

Chris Morris: If you listen to the pre-Big Star bands, Icewater and Rock City, there’s this kind of slow-moving element, this kind of shifting, viscous quality to the writing. That’s Chris, that’s not what Alex Chilton brought to the Big Star table. It’s also extremely present on #1 Record. Then you hear it full-blown on I Am the Cosmos, especially on the title song. It’s kind of like the sound you’d hear if honey were dripping down the walls of the Sistine Chapel. It’s this slow, beautiful, liquid sound. No one else that I can think of before that was doing that. It doesn’t hit you

over the head like a lot of rock ’n’ roll.

Throughout the Rock City sessions, Chris, Andy and Jody kept up Icewater’s live act. After a few months, Alex made good on his promise and attended one of their gigs. At the show, held at a Veterans of Foreign Wars hall in downtown Memphis, Chris handled lead vocals and played a mix of obscure covers and some originals. After the set, Alex met with Chris, who’d recently turned twenty. Chris again suggested Alex move home to Memphis and join the band and work on their songs at Ardent, a tempting offer for a man with a batch of new songs. The still-bitter Box Top wasn’t keen on the idea of joining another band, but he was impressed with the power trio’s live performance. Plus, after Alex’s sublet apartment agreement expired, his parents’ spacious Midtown Memphis home became more appealing.

Andy Hummel: At some point, Chris had a conversation with Alex.

Richard Rosebrough: They’re talking and exchanging song ideas. That’s when those two energies started meshing.

Jody Stephens: Chris wanted Alex to join the band as soon as he heard Alex might move back to Memphis.

Chris Bell: Alex came down to Memphis from New York and had heard us play…We spent a couple weeks formulating plans and were excited.

Carole Ruleman Manning: Alex and Chris were such different personalities. It was hard for me to think of them in a songwriting relationship. I didn’t see it as something that would work so well.

A second Bell-Chilton meeting happened in February 1971, at Ardent Studios. It further bonded the two songwriters and solidified Alex officially joining the yet-to-be-named band (Chris dropped the Icewater moniker). Together, on a whim, they laid down “Watch the Sunrise.” Alex had also already penned “In the Street” and “Te Ballad of El Goodo.” Chris had his Rock City songs and some new tracks in the hopper. The stars aligned.

Chris Bell: Alex had come along to play in the studio with Andy, Jody and myself. I played him a couple of my tunes and he played some of his and we both dug each other’s songs.

Andy Hummel: The first hook-up with Alex was with Chris, Steve, and me—maybe Jody was there. Alex showed up and got out that wonderful Martin twelve-string he had and played “Watch the Sunrise” and we recorded it. I thought it was an amazing and wonderful song. The guy was obviously super-talented. He didn’t sound a thing like he sounded in the Box Tops, which was cool with me.

Steve Rhea: By this time, Alex began to sing in his higher register, but he still had that tried-and-true voice.

Chris Bell: In that rehearsal studio, it was really happening. There was a certain magic about the stuf we were doing.

Andy Hummel: Alex and Chris recognized each other’s talent and were drawn to each other. Chris had access to Ardent and Alex had the name. Plus, they were both Capricorns. It just synergized.

Alex Chilton: Chris asked me to join the group and I did, but I didn’t have any ideas about a rock band so much. It was a couple years later before I decided how I really wanted to approach things in a rock ensemble.

Chris Bell: Alex had already done [the 1970] album with Ardent, which wasn’t released. It’s still in the can. One of the tunes of this album is “Free Again,” or something—it was changed around and made into “Give Me Another Chance” for the first album. Anyway, that album fell through and at first Alex was pretty skeptical about Ardent when we formed Big Star because of that experience. I convinced him it would be a good idea.

Alex Chilton: He asked me to join his band and I had been listening to Chris’ bands for years at parties, so I was excited about doing that. In ’71, when we started recording and practicing, I came back to Memphis from New York and started hanging around at Ardent again.

Jody Stephens: We thought he’d make a great addition. Alex’s tastes were more American than ours, although he dug the Kinks and the Zombies, so it was a strange combination.

Alex Chilton: It was a band that got together to play that sort of music. I mean, those guys didn’t care for black music at all. You couldn’t get them to listen to “Scratch My Back” for anything in the world.

Andy Hummel: The band, except for Alex, was together for about six months before that. Then he came into town and we got him to be in the group and then we started practicing.

Chris Bell: As Big Star was starting rehearsals, Alex decided he would come to Memphis and stay with the group.

Andy Hummel: We hooked up and started playing a lot, almost entirely in the studio. Shortly thereafter it was like, “Alex is going to join the band.” Everybody thought that was cool. It took of from there because Alex had some songs.

John Fry: Right from the start, I thought it was great. What they were doing was amazing. I let them have access to the studio as much as possible. I was like, “Hey, I trust you guys. Don’t trash the place and make sure you lock everything up and make it ready for in the morning.”

Andy Hummel: I guess we talked a little, like, “Here’s a guy who can go to any record company and get a contract and record anywhere he wanted to.” It was cool Alex decided to hang around Ardent and join up with us. It always seemed a bit odd for me, but certainly fortuitous for us. It remains, to this day, a bit of a mystery as to why he wanted to come and play with us.

Danielle McCarthy-Boles: Alex had been there before, and Chris dreamt of that life. In some ways, Alex was the seasoned veteran and Chris was the naïve, excited dreamer of the two.

The band was still in its genesis when it was promised a recording contract by John Fry, who saw promise in the Bell/Chilton songwriting partnership. Ardent’s newly re-launched record label was rejuvenated after it signed on as a rock subsidiary of Stax Records. The first band signed to the label was Cargoe, a Tulsa, Oklahoma-based rock group produced and mentored by Terry Manning.

John Fry: Stax had been talking to Ardent about being the rock brand for Stax. Al Bell, who was the president at Stax, said if we wanted to do that we could have this label and sign all the artists we wanted, but they would do the marketing, promotion and distribution. Of course, we said, “Yes, we would love to do that.” Chris and the other guys knew about that and we had already said, “If you get a band together and some material, we will do an album.”

Andy Hummel: When the notion was expressed, “Hey, let’s record an album,” there was a whole new layer of stress added on the band—now we’ve got to produce a product. You can’t just write and record at your leisure. It can’t be just fun all the time anymore, there’s a work aspect to it.

Al Bell: I considered Fry, Dickinson and Manning to be unique creative geniuses. I had tremendous respect for them and I felt the same way about them that I did about Steve Cropper and Jim Stewart. They needed someone who saw their vision and could turn them loose and I had a sense of the artistry they were seeing. I wanted to help with what assets we had, the way they’d helped us with “Soul Limbo.” I thought these guys could do for rock what we did for soul.

Carole Ruleman Manning: There was a need for Stax, they thought, to have a rock and pop presence in the company, a crossover into that market. Ardent, of course, wanted to release some of this product it was putting together. It was a natural relationship.

As Chris and Alex sharpened their growing list of songs, Stax signed a threeway deal with Ardent Records. The world-famous soul label acquired Ardent’s manufacturing, merchandising and distribution rights. In an April 1, 1972, Billboard interview, Al Bell called it one of Stax’s “most significant expansion moves in years.” The grassroots vacuum Chris operated in was suddenly a part

of a bigger machine.

Steve Rhea: Stax had made a run at having a label that would release pop-type music for years. Terry Manning had his Enterprise label with them. They were always kind of testing the waters, and none of it ever hit. When Ardent made a distribution deal with Stax they were going down a road that had been tried before and John and Terry would have to tell you why they thought it would work that time. Terry Manning was heavily involved over there at Stax, and John believed if we pooled all these resources we could get the job done.

Carole Ruleman Manning: There was so much excitement at Ardent. The excitement of a new company with a new release and a new distribution deal with Stax. While #1 Record was being recorded at Ardent, there was a lot of excitement. There was a positive feeling that things were going well. We perhaps had unrealistic expectations.

Richard Rosebrough: John Fry was able to finance the whole thing. It helps to be on John’s good side for him to help you out financially. John believed in them and was willing to stay with them from start to finish.

John Dando: Fitting into the Apple mode, John Fry was their Brian Epstein.

Richard Rosebrough: John Fry, Terry Manning, me and the others that followed us, we were all engineers at Ardent. We all had our own pet projects at Ardent. We were all hoping individually for some success. Big Star became Fry’s pet band. He liked them. He enjoyed their company. He enjoyed their youth. Fry thought they were writing brilliant songs and of all the bands coming in to Ardent, they had the best chance of making it.

Andy Hummel: If there hadn’t been an Ardent, there wouldn’t have been a Big Star.

Chris Bell: At this time, we were just playing, jamming together as a band, but we didn’t have a name and such. One day, after a session, which John Fry was engineering, we stepped out of the studio for a while and right across the street was a Big Star food market. We thought, “Hey, what a great name for a group.” We trooped back into the studio and said to John, “Oh, by the way, we’ve got a name—Big Star.” And that was that.

Alex Chilton: The name Big Star was just sort of a joke. It was the time of glam and glitter rock. The name just seemed to be right for the times.

Andy Hummel: The name Big Star was just desperation. We needed a name, and nobody could think of one. We were sitting out in between the old shack on National and the actual storefront studio, smoking—something—and there was the Big Star grocery store right across the street. Somebody said, “Let’s call it Big Star!” I guess it was just a flash of brilliance. All I was thinking was, “That’s awfully presumptuous. What are people going to think when they see that in stores?”

There Was a Light: The Cosmic History of Chris Bell and the Rise of Big Star by Rich Tupica, is now available in paperback by Post Hill Press.

Copyright © Rich Tupica, 2020. All Rights Reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the author.