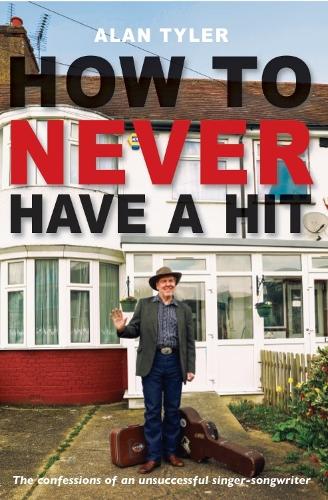

Alan Tyler has spent decades making music on his own terms. In How to Never Have a Hit, he looks back with humour and sharp insight at a life in songwriting, the near-misses, the wrong turns, and the moments that made it all worthwhile. From The Rockingbirds to his solo work, he’s seen the industry change but never lost his love for it. He talks to Jason Barnard about the book, the music, and what keeps him going.

Your book title, How to Never Have a Hit, is either a lesson in self-deprecation or the most niche how-to guide ever written. Was there ever a moment when you thought, ‘Hang on, I might actually have a hit here’?

Yes, I think the book might be a hit; it’s early days. The art lies in pleasing the reader, and I’ve had many messages of appreciation from all sorts of people so far which encourages me to think I’ve done a good job. To snatch victory from the jaws of defeat with a successful book about a career of commercial failure is the “dream” that drove me on to write it. My intention was not to sell it to a few hundred fans and friends (though I have managed to do that, so far, thank goodness) but to produce something readable, entertaining and thoughtful that has a wider appeal. Time will tell. The odds are against it being a bestseller, of course, because I haven’t got a huge fanbase, and that’s why publishers turned me down, and I self published. As I say in the book, “success is relative, achievement is absolute”. At the end of the day you can only do what you set out to do, and I’ve done that and I’m pleased. I think the book is the best thing I’ve ever done.

Having spent decades navigating the music industry without ever ‘breaking’ in the traditional sense, if you had to sum up the experience in one golden rule, your own ‘Tyler’s Law’, what would it be?

There’s a bit at the end of the book where I copy something George Orwell did in “Down & Out in Paris and London” by making a pithy list of my lessons learned. “Be chatty and friendly” was one thing on the list – I often wasn’t. Always use modern state of the art recording equipment was another – we sometimes didn’t…The Tyler’s Law I would pick from the list is:

“Believe in magic, but don’t only believe in magic. Music can be a nice job, but it is still a job, and the only way to get the magic to work is to work.”

A lot of the story about what went wrong with The Rockingbirds and other projects was I simply wasn’t workmanlike enough. I was guided or distracted by airy-fairy romantic ideas and failed to do the basics of turning up and doing the job I was being paid to do.

The Rockingbirds were country before country was cool (or at least before the Americana boom) and played Reading ‘92 on the bill with groups like Nirvana. Was there ever a moment backstage where you thought, ‘Wrong decade, wrong genre, wrong audience’?

No, absolutely not! I always wanted to be different, that’s just me. To go with the flow and do what other people around me were doing would have been boring, and I’d have produced nothing. The book is a case study in contrarianism. I don’t regret us being the only country-rockers in town, or being a jazzy, swingy tap-dancing songwriter before that. My main cause for regret was going off the rails in 1992 just at the moment we were being given our once in a lifetime opportunity, with the Sony/Heavenly Record deal and all the media attention, TV, radio and festivals. When success came near I started running in the other direction…I just got drunk too much and stopped writing and working; I took my foot off the gas, my hands off the wheel, and the vehicle I was in charge of veered off into a ditch.

After decades of making records, what’s the song you’re proudest of? And which one makes you wince and pretend you don’t remember writing?

Jonathan Jonathan, my tribute to Jonathan Richman, is perhaps my best known song and probably deservedly so. I’m very proud of that one, but most of my songs that are out there I am happy with. I would choose perhaps A Good Day For You Is A Good Day For Me as my least liked, partly because it’s rather lightweight, but mainly because we made it the A side of our first single, relegating Jonathan Jonathan to the B-side, a mistake I go into in the book. We did a different version of Jonathan later for the album and made that an A-side, but to be honest I prefer the earlier recording.

Your lyrics often blend social history with personal storytelling (e.g., ‘Middle Saxon Town’). Do you see yourself as a historian as much as a songwriter?

Yes, that’s a big strand to what I do. There are the river songs (place specific songs about natural and social history) like Down On Deptford Creek, Essex Girl etc. Jonathan Jonathan is also a history, mixing biographical details of Jonathan with my own story. And the book is that too, of course – but it’s not just the story of my musical career, it’s about the places I’ve lived, jobs I’ve done, the cultural and political changes over the decades, the relationship of pop music with politics (especially the left) geopolitics even, London, changes in technology, changes in social attitudes… All sorts of things that (hopefully) readers will recognize from their own lives, the changes we have seen over the decades.

Has the digital age been a help or a hindrance to a musician like you? On the one hand, streaming gives longevity, but on the other, those early DIY days must feel like another world now.

You work with the media you have available to you. Technology has driven pop music forward in my lifetime in many ways but what we see now is more destructive than constructive. People of my age had opportunities to express themselves that were unknown to people a few decades before us. We were very fortunate. Technology was very enabling, and DIY record making became a commercial reality just as I came of age and started participating. But then it was all done very collectively in groups and was very place based. I’m not talking just about venues but in towns and cities and communities like housing co-ops and squats and so on, which I write about in the book. The Camden indie scene etc, the alt-country scene in London post 2000. All this, sadly, is vanishing, as music making is now atomised into individuals working from home studios and sharing online. Real bands are mostly a thing of the past. Venues and clubs are unsustainable. Our once thriving music culture is dying before our very eyes. There are exceptions, some things keep going, some things spring up, and hopefully they always will, but we have lost so much.

The Americana Music Association gave you the Grass Roots Award, which you accepted with mixed feelings. Is there something poetic about finally getting an award that specifically wasn’t for being a musician?

I don’t know about poetic…I put that little episode in the book because it served my narrative and I thought it was funny, a bit weird even. What were they thinking?! The book is written from a standpoint of a certain incredulity at what people do and see, individually and collectively, and at what I have done myself, of course. Why did I do that? I ask myself at various times. But also, “why can’t people see that what they are doing is wrong or daft?” The disagreement me and Andy Hackett had with Edwyn Collins and Grace over the recording quality of our 2nd album is an example I give in the book. Why can’t they hear what we hear, we asked?? My incredulity comes to a head in the final Yesterday’s Chips chapter, where I write about group-think and social media spats over politics. We now live in our screens in an online simulacrum where people are ruled by mad or bad ideas that are unmoored from reality. I found it profoundly alienating and closed my social media accounts, cancelling others before they cancelled me. My point of view is the post 2016 “post truth” era is universal, not just a right wing thing. On one level the book describes a journey of alienation from the greater analogue reality of the past into the strange, meme-driven digital unreality of the present.

If you could go back and tweak just one decision in your career, what would it be? And do you think it would have made a difference?

I shouldn’t have edited out the “being late is better than never” middle eight section from the 7” single edit of Gradually Learning, to make room for the intro and outro that I was attached to. That’s an example of a “bad” decision which, if righted, might have made a difference. The producer and the label might have been a bit more controlling, at times. But I honestly doubt it would have changed anything. And I’m definitely not blaming anyone else… I own all the mistakes. I’m happy the way things came out and I’m happy with what we achieved and where we ended up. I think it’s a good story.

Further information

Alan Tyler: How To Never Have A Hit out now. Signed copies are available via Bandcamp and from Rough Trade shops. Also available from The Great British Book Shop, and from most other online booksellers. Kindle edition from Amazon