Scott Shea dusts off the nearly forgotten legacy of Chad Allan, the modest visionary whose quiet exits inadvertently launched two of Canada’s biggest rock exports: the Guess Who and Bachman-Turner Overdrive. Shea’s portrait is a clear-eyed, compassionate look at a man who kept choosing the shadows over the spotlight, even as his influence rippled through decades of North American rock. It’s a story of the kind of understated grace rarely credited in rock history.

Shadows Cross the Shadows

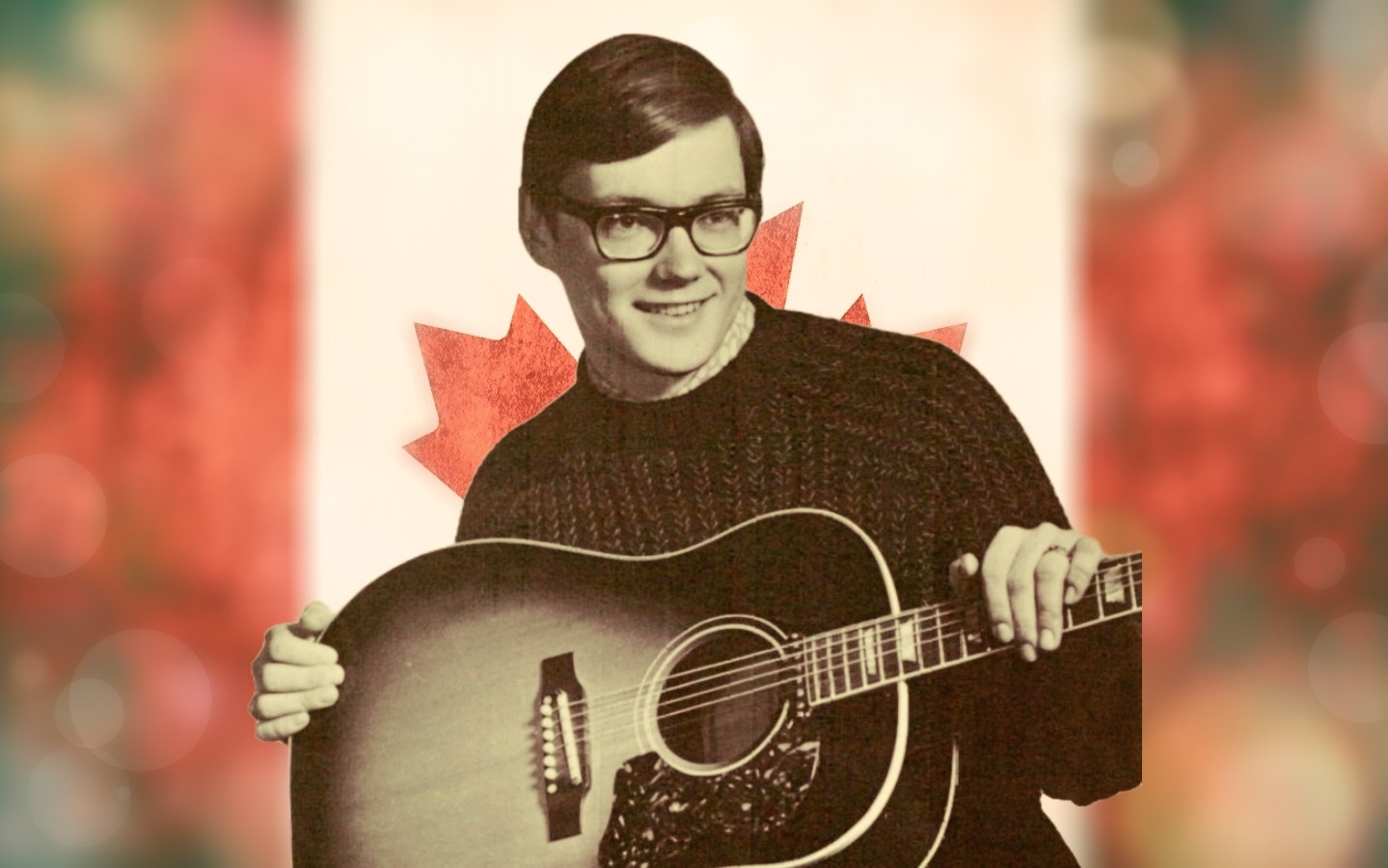

In early December 2005, John Mackie, a writer for the Vancouver Sun, was dispatched to Marpole Family Place, a senior living community that had been serving the Canadian city’s elderly population since 1978. His subject was a thin, wispy, silver-haired man who was there to play the oldies for residents with his accordion. His repertoire ran the gamut, beginning with timeless old favorites like “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary,” “Bye Bye Blackbird” and “Moon River” and transitioned to early rock and roll songs long like “Flip, Flop and Fly” and “Great Balls of Fire.” His name was Chad Allan and the seniors bopping along to the wheezes from his squeeze box could never have guessed that over 40 years earlier, he started Canada’s first great classic rock band, the Guess Who, and followed that up in 1971 by co-founding another one that would eventually morph into Bachman-Turner Overdrive.

His third act was to disappear into obscurity and become seemingly forgotten by the bandmates and fans who benefitted from his ambitions. His story with both groups is a combination of his love for music, dogged determination and some dumb luck, but neither would’ve happened without him. In both cases, a supremely talented singer was recruited who took control and caused Chad to fade into the shadows. The other common thread was his friendship with guitarist Randy Bachman who filled a hole when he was in need and later lean on Chad when it seemed like he didn’t have a friend in the world.

Back in the Spring of 1969, the Guess Who burst onto the music scene out of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada with “These Eyes,” a beautifully crafted pop song, co-authored by guitarist Randy Bachman and lead singer Burton Cummings that peaked at #6 on the American pop charts. The song nicely balanced the poppy and the heavy of the day with a catchy melody initiated by Burton’s moody keyboard cadence and the gentle muting of Randy’s Gretsch. Over the next year-and-a-half, together and alone, the two would perfect their songwriting formula and pen several more Top 10 hits, including the number ones “American Woman” and “No Sugar Tonight,” and cement their status as elite level hitmakers.

Additionally, the Guess Who were one of a few acts who resonated on the relatively new FM album rock format, which mixed harder-edged, less commercial rock music from groups like the Grateful Dead, Cream, the Moody Blues and Jimi Hendrix and newer more progressive offerings by tried-and-true artists like the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Who and Bob Dylan. The Guess Who dropped right into this period with hits that dazzled AM playlists and deeper, harder tracks that whet the whistle of freeform DJs on progressive stations like KSAN in San Francisco and WNEW in New York. Little did they know that the Guess Who had been kicking around in various incarnations for the better part of a decade and earned their master’s from the school of hard musical knocks.

Back and Forth

The story of the Guess Who began in 1958 when 15-year-old Allan Kowbel, as in “more cowbell,” of Winnipeg purchased his first guitar, a Silvertone model from Sears. It was a common, inexpensive starter model used by many teenagers in rock and roll’s first generation and inspired the name of his first band, Allan & the Silvertones. He and bandmates Johnny Glowa, Brian Donald and Ralph Lavalley played local parties and school dances for about a year while students at Miles McDonnell Collegiate where they learned the tricks of the trade. Like most teenage bands, the Silvertones endured several personnel changes, but fate intervened in 1959 when Allan crossed paths Jim Kale, a bassist from rival band, the Jayhawks. After some coaxing, Kale defected to the Silvertones, which now included Bob Ashley on piano and Larry Wah on guitar. They honed their skills at local venues like the Crescentwood Community Club, the River Heights Community Club and the Brandon Roller Rink where they opened for bigger rock and roll acts like the Ventures, the Johnny Burnette Trio and Conway Twitty.

In 1960, two major milestones in the history of the band took place. First, Allan Kowbel became Chad Allan. The Silvertones’ reputation was growing, and he felt his last name wasn’t sexy enough for rock and roll, so he made Allan his last name and adopted Chad from his favorite folk group, the Chad Mitchell Trio. He also renamed his band the Reflections. Shortly after that, Larry Wah quit and a new rhythm guitarist was needed. The Winnipeg music scene of the early 1960s had an embarrassment of riches in terms of young musical talent and can properly lay claim as the hometown of Neil Young, Terry Jacks, Bruce Palmer and an eager young guitarist named Randy Bachman.

Randy first came to the attention of Jim Kale who invited him to come audition for the band. He was taught by Lenny Breau, a renowned guitarist from the Breau Family, a traveling country band led by his parents Hal and Betty who’d relocated to Winnipeg from Maine in 1957. Randy’s devotion to mastering his guitar got him kicked out of school but Chad recognized his talent and gave him his first professional gig. Shortly after, Randy suggested that they recruit a better drummer and recommended his friend Garry Peterson. Garry was already a member of the American Federation of Musicians and had drumming in his blood. He’d been taught by his professional drummer father and was currently involved with the Winnipeg Junior Symphony. It wasn’t hard to convince him to give up the symphony for rock and roll and he, Chad, Jim Kale, Bob Ashley and Randy stuck together for the next three years. More importantly, however, was that three-fourths of the classic Guess Who lineup was already in place.

This band of untapped talent caught the ear of CKY disk jockey Herb Britton, who also happened to be the Winnipeg rep for Canadian American Records. The label had recently put its name on the map with hits by Santo & Johnny (“Sleep Walk”) and Linda Scott (“I’ve Told Every Little Star”) and showed a good ear for young talent by issuing an early Paul Simon record under his pseudonym Jerry Landis. Chad Allan & the Reflections signed with the label in 1962 and released their debut single, Geoff Goddard’s “A Tribute to Buddy Holly” backed by an original instrumental entitled “Back and Forth.” It did well locally so they were allowed a follow-up, but the torch ballad “I Didn’t Have the Heart,” written by Chad, couldn’t find a place and the label dropped them.

Nevertheless, their audience was steadily growing and that was enough to get them signed to Toronto-based Quality Records. Chad Allan took another stab at songwriting, authoring their first few singles for the label, “Shy Guy,” “Inside Out” and “Stop Teasing Me,” but all three struck out. Their popularity still continued to grow locally, and they began playing regularly at the Gold Coach Lounge and the Town & Country Nightclub. Both were in proximity of the University of Manitoba where Chad Allan was taking courses in physics. It was his Plan B, but as long as their reputation continued to flourish, that stayed on the back burner.

A Promotional Gimmick

Although still signed to Quality, Chad Allan & the Reflections’ recording status was in limbo and their future with the label seemed murky. Complications arose back in April 1964 when a Detroit-based ensemble also called the Reflections jumped into the Top 40 with “(Just Like) Romeo and Juliet” which peaked at #6 at the end of May. Quality attempted to get ahead of any legal conflicts by issuing their lone Reflections single of 1964, “Stop Teasing Me,” as Chad Allan & the “Original” Reflections, but it made no difference. To avoid any confusion or potential lawsuits, Chad and the group made the difficult decision to change their name altogether regardless of what it might cost them locally. Since the goal was a national breakthrough, they henceforth became known as Chad Allan & the Expressions.

Since they needed to win back Quality’s favor and understanding his original compositions weren’t making it, Chad went in search of that elusive cover song with a catchy hook that nobody had heard before. The Rolling Stones were making a living doing this at this point of their young career with hits like “It’s All Over Now” and “Time is on My Side,” so he decided to try that approach. The song he was looking for came through his friend Wayne Russell whose cousin regularly mailed him the latest and greatest records from England. One such gem was Johnny Kidd & the Pirates’ “Shakin’ All Over,” a rip-roaring, guitar rocking dance tune that shot to #1 in England in 1960 but was heard nowhere else. Chad played it for the band and all agreed to cut it. They were excited with their rehearsals, but Quality was hesitant. Since they’d released three duds in a row, the label wasn’t very keen on ushering them into a studio anytime soon. New band manager Bob Burns, host of the popular Teen Dance Party on CJAY-TV, took matters into his own hands and arranged for them to record the song at the TV station on a cold Saturday night in December.

The result was a harder, edgier and slower arrangement of “Shakin’ All Over” that featured an impassioned lead vocal from Chad. Bob Ashely’s clicking piano also gave the song texture unheard on the original, but the clincher was Randy Bachman’s frenetic Gretsch strums that shook the listener. The maniacal screams from the band throughout elevated the older tune to thoroughly modern and everyone involved agreed that they had a bonafide hit on their hands but weren’t sure if their label would agree. They hadn’t come close to a hit and Quality seemed more content to let the group fade away and not even compete with the stiffer chart competition, which was now dominated by British bands. The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Gerry & the Pacemakers and the Dave Clark Five had refashioned the rhythmic sounds of first-generation rock and rollers like Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Little Richard and Buddy Holly into something fresh and exhilarating. They’d taken the Western world by storm, and, in North America, if you weren’t British or didn’t sound like it, disk jockeys were hesitant to play your record. Chad Allan & the Expressions new song sounded British, but their fear that this great record would be dead on release was very real.

Nevertheless, “Shakin’ All Over” was initially released in December 1964 as the B-side to “Til We Kissed,” and credited solely to Chad Allan. Someone at Quality Records hadn’t gotten the memo on the band’s name change. Label executive George Struth also was a believer and knew that he had a hit on his hands, so he decided to be proactive and developed a clever strategy. He had a small number of advanced promo copies made up with just a plain white label and the song title in big, bold, black letters at the top. On the bottom, it simply read “Guess Who?”. There was no mention of a record label, who the group was or where they were from. He mailed them out to stations across Canada in January 1965, and the sheer spectacle of the disk piqued a lot of DJs’ interests. Struth believed that anyone with a pulse would be tapping his toes and nodding along with the beat from the first note. He may have even started a rumor that the mystery single could be the latest offering by the Beatles. His gamble paid off. Soon afterward, it entered the charts as “Shakin’ All Over” by the Guess Who? and hit the number one spot in Canada in a matter of weeks. Even when it was revealed that the group was actually Chad Allan & the Expressions, disk jockeys still kept calling them the Guess Who? This moniker got so popular that the next two follow-ups were issued as Chad Allan & the Expressions with “Guess Who?” typed in parentheses.

The fast success of “Shakin’ All Over” in Canada made U.S. labels take notice, but curiously didn’t spur many to action. The New York label Scepter, a mostly R&B label with Dionne Warwick, Chuck Jackson and the Shirelles on their roster, were the first to make an offer and Quality jumped on it. They repeated the same mystery process in March, and it peaked on the Billboard charts at #22 in early summer. Its success prompted Scepter executive Paul Cantor to invite the band on the “Louie Louie Tour,” an East Coast jaunt that also featured the Kingsmen, Sam the Sham & the Pharaohs, Dion, the Turtles and Barbara Mason. Cantor was New York slick and told the band how much money they’d make and that they’d be on the Ed Sullivan Show, which never happened, all the while insisting that they make the 1,700-mile journey on their own dime. When they met up, he rewarded them with a whopping $400, their share of a quarter-million copies “Shakin’ All Over” sold in the U.S. As their relationship progressed, it became clear that Cantor was long on promises and short on results. The pay was paltry and all five shared a room most of the time, but they didn’t care. This was the big time!

Cantor did, however, record some sessions with the group and brought in staff songwriting teams like Ashford and Simpson and Gary Geld and Peter Udell to pitch songs directly to them. Afterwards, they were whisked into the label’s brand new studio in on 254 West 54th Street, future home of famed 1970s discotheque Studio 54, and recorded several for their debut long-player, “Shakin’ All Over.”

After that tour ended, they followed it up with another one featuring the Crystals and the Shirelles, where they also served as their backing band. They hit the U.S. South at the peak of its resistance to desegregation and were greeted often with vitriol and the threat of violence for traveling together with black performers. They arrived in Chicago’s Garfield Park neighborhood on August 12th, just in time to witness firsthand the race riot sparked by the Wilcox-Pulaski fire station’s ill treatment of its mostly black neighborhoods.

Turn Around and Walk Away

By the time Chad Allan & the Expressions returned to Winnipeg, they had spent the entire summer and the early part of fall in the United States recording and touring, nd it took a toll on Bob Ashley. The shy, introverted, classically trained pianist came to the band from the Canadian Wheat Board where he served as a clerk and their sudden success was unnerving to him. Also, Ashley was latently homosexual and keeping up the charade with his sex-charged bandmates was difficult for him emotionally. During the Crystals’ performances of “He’s A Rebel,” the girls would throw a leather jacket on him and bring him on stage, which embarrassed him greatly. Come December, he resigned from the band, effective immediately. He kept a low profile in Winnipeg for a couple of years, playing piano in nightclubs and restaurants, and in 1968 left for Toronto with singer Annabelle Allen. He eventually moved into teaching dance at York University and worked in several local theater productions. His tenure with the Guess Who gradually faded to the point that hardly anybody remembered he ever was a member.

It was quite a loss for the band, though. Ashley was incredibly gifted and served as their de facto musical director in those days. He came up with the idea of thumb tacking a couple of violin pickups to the back of the piano so that it could be heard over all the other instruments during live performances, which separated them from rival bands. He also helped Randy Bachman develop a custom-made echo machine out of a repurposed Korting tape recorder that gave his guitar the slap back echo delay so prevalent in Elvis’ early records. Chad Allan filled his spot for a couple weeks, but a replacement was needed and fast, especially now that they were Winnipeg’s top dogs. While they had been in New York, several of their hometown gigs were taken over by an up-and-coming local group, the Deverons, which featured 17-year-old Burton Lorne Cummings on keyboards and vocals. After a brief discussion, the band decided to make him an offer, which he accepted.

Burton made his Guess Who debut in January 1966 just as the group was trying to match the success of “Shakin’ All Over.” Subsequent singles did well in Canada but weren’t registering at all in the U.S. or elsewhere. The grind began taking its toll on Chad who was also moonlighting as a college student. Education was always a priority in his life and, for as long as his band had been in existence, he was supplementing his future by pursuing his Bachelor of Sciences as best as he could. The summer tour was not fun for him, and he disliked life on the road and industry pressures like following up a #1 hit. When Burton joined, he decided to resume his classes at the University of Manitoba and leave the Guess Who. He made his desire known to his bandmates around February 1966, but there was just one problem. Quality Records wanted a new album, and sessions were scheduled to begin in a little over a month. All agreed that Chad would play on the album and depart after its completion.

“It’s Time” was released in June 1966 and Chad left to start his new life. Over the years, he’s given many reasons why he left: education, throat problems from never learning to sing from his diaphragm, his recent marriage, touring fatigue, and others. The Edmonton Journal reported in October 1966 that he left to become a folk singer. But the elephant in the room, Burton Cummings, was never given as a reason. The writing must’ve surely been on the wall when the devilishly handsome singer joined and, no doubt, Allan was able to read it clearly, especially since Burton was no shrieking violet. He was a multi-threat. He could sing, play, dance and was good-looking. The reaction he got from the girls in the audience was unprecedented and was countered by Chad’s marked unhipness. The short hair and Buddy Holly rims were old hat by 1966, and Burton was sporting a modern Beatles cut that the rest of the band imitated. But perhaps the biggest contrast of all was vocal strength. Burton’s voice was stronger than Chad’s, albeit similar. Both had a nasal tonality reminiscent of Cliff Richard and Burton could sing all the old Expressions songs and nobody outside of Winnipeg would have any idea he wasn’t the original guy. They split the lead duties on “It’s Time” eight to four, in Chad’s favor, but there are times when it’s difficult to distinguish which one is doing the singing. When it was over, Chad walked away from the band forever, or so he thought.

Let’s Go

A lot can happen in a year’s time and to an observer like me, the difference between 1966 and 1967 can seem like night and day. It’s almost like the entire world switched from black and white to color TV and it couldn’t have been more evident than on the Canadian television show called “Let’s Go.” The musical variety program aired weekdays on CBC at 5:30 pm from a different major Canadian city each day. Thursday’s show emanated from Winnipeg. It was originally called “Music Hop” and featured Alex Trebek as its original host. It went through a series of iterations over the next three years, and in 1967 received a swinging makeover and was rebranded “Let’s Go.” The Winnipeg show was hosted by none other than Chad Allan, who’d performed on “Music Hop,” and the Guess Who was brought in as the house band.

It was an interesting if not awkward reunion. Chad received his college degree but could never fully shake away performing. Not long after leaving the Guess Who, he was playing Winnipeg college clubs with makeshift groups like the Chad Allan Trio and Chad Allan & the Sticks and Strings. When the CBC came calling, it was an opportunity to get back into the spotlight and maybe make a record. For the Guess Who, it was an act of desperation to keep their heads above water. Their third single following Chad’s departure, a Johnny Cowell slow dancer called “His Girl,” jumped into the Top 50 in England in January 1967. Swinging London was hot, so manager Bob Burns seized the opportunity and put together a British tour. There was much fanfare from family, friends and fans at the airport as they were leaving, but when they arrived, there were no concerts, no contracts and no money.

It seems that Burns got bamboozled by the front-man Quality Records dispatched to England ahead of time to set everything up, but his ignorance didn’t stop the band from firing him when they returned home nearly $30,000 in debt. They owed large bills to Air Canada, Gar Gillies’ Gurdian Amplifier Company and their clothier, the Stagg Shop, and had no foreseeable income as they’d cancelled a month’s worth of good-paying gigs to make the tour. Relief came that Spring in the form of CBC producer Larry Brown who offered them the “Let’s Go” gig after a successful audition. It paid $1100 a week and allowed them to make substantial payments towards their debt.

The reunion of Chad Allan and the Guess Who on television gave a clear picture of the different roads each were taking. While the band dressed the part of a hip rock and roll band, Chad looked collegiate with horn-rimmed glasses and his dress ranged from a cross between a hatless mad hatter and an English dandy to modern tieless polyester chic. The stark contrast was almost Pete Best-ian. The difference was also evident in the song selection. Chad sang solo numbers like Bobby Russell’s “Honey” or the Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Daydream” and tackled the contemporary pop group sounds of the Mamas & the Papas and the 5th Dimension in the academically named quartet, the Good Time Music Appreciation Society. The Guess Who, on the other hand, looked the part of a trending rock and roll band in a post-Monterey Pop world and performed newer songs by Vanilla Fudge, the Doors, Cream and other harder rock acts. It proved beneficial as the time they spent rehearsing and recording these edgier songs contributed to their development as a contemporary rock band. During their “Let’s Go” tenure, Randy Bachman and Burton Cummings teamed up to write future hits like “These Eyes,” “No Time,” “6 a.m. or Nearer,” “A Wednesday in Your Garden” and others, and were allowed to debut them in the show’s second season.

In the 65 plus episodes of “Let’s Go,” the Guess Who not only paid off their debt, but their dues as well and transformed their sound into something completely unique. They bought out their Quality contract to sign with Nimbus 9, run by independent producer Jack Richarson who would produce their second international hit, the Bachman-Cumming composition “These Eyes.” Released first in Canada in November 1968, it would hit #6 in the U.S. and begin a hitmaking run that lasted through 1974. Richardson would go on to produce 11 albums and 10 hit singles, including their signature song, “American Woman,” and set up a U.S. distribution deal with RCA Victor.

Chad Allan’s career did not take the same trajectory, although he wasn’t necessarily aiming for that. He was an introvert, something he attributed to being an only child, and wasn’t interested in the rock and roll lifestyle. After the cancellation of “Let’s Go” in 1968, he formed the Metro-Gnomes with some of the Good Time Music Appreciation Society singers and put out an album in 1969. He remained with CBC in various capacities while pursuing a second bachelor’s degree in psychology and was preparing to take a teaching job in the Winnipeg school system when another reunion took place in the halls of the CBC that pulled him back in the pop music game.

Another Way Out

The Guess Who reached dizzying heights in 1969 and 1970 that they never could’ve envisioned back in their Expressions days. Following “These Eyes’” U.S. chart placement, they followed up with five more Top 25 hits, four of which placed in the Top 10 and two of which hit #1. Their unique original songs, bolstered by Burton’s powerful light baritone that easily revved into overdrive, was more rock than pop and they were equally as popular on the album-oriented FM band as they were on Top 40 AM stations. Not only that, but they were an in-demand live act whose touring price grew exponentially and every musical TV show wanted them to perform. It was the stuff of dreams, but all dreams must end, and this one did in a dramatically swift manner.

As “American Woman” was ascending to the top of the charts in the U.S. and Canada, Randy Bachman was now feeling the pressure. He’d come a long way since joining Chad Allan & the Reflections and there were a lot of ups and downs along the way that took a toll on his health, but nothing more than the constant touring. In 10 years, he hadn’t had much of a break and the unhealthy combination of stress and a bad diet caused him to develop incredibly painful gallstones. He had to step away in the middle of their tour that started back in February to be under a doctor’s care and initial reports stated that he’d be out six weeks. His temporary hiatus lit the fuse for his bandmates to force him into a do or die decision. On the face of it, it seems like an extreme reaction, but it had been a cumulative effect.

With the tremendous amount of success that followed “These Eyes,” and having the golden touch, Randy was looking to start a Beach Boys-esque musical empire. He formed his own publishing company, Ranbach Music, recorded tracks for an instrumental solo album in Chicago in mid-March 1970 and began producing other artists. It caused his bandmates, who continued to grind it out on the road, to grow bitter. Those things, in and of themselves, would’ve been to their benefit, but it appeared to them that Randy desired to step away in Brian Wilson fashion and work on their brand rather than tour with them. What compounded the problem, and was most likely its source and summit, was Randy’s desire to spend more time with his family. He married Lorayne Stevenson, a devout Mormon, in 1966 and started a family. By 1969, he’d converted to the faith and became clean of mind, body and spirit much to the consternation of his bandmates who enjoyed imbibing on drugs, alcohol and women. It drove a wedge and split them three-to-one. While the others were partying with groupies after shows, Randy would go to his room to be away from it all and it irked Burton, Garry and Jim who began calling him “the Narc.”

When they called his home from the road on May 15th in Springfield, Massachusetts and discovered he was in New York lobbying RCA execs to sign the Mongrels, whose record he’d produced, it was the last straw. They jumped in a car and drove straight to his hotel in New York and prepared for a confrontation. After a heated discussion in Randy’s room, Burton told him he was fired. Randy responded by telling them he quit and just like that, the classic lineup of the Guess Who was gone and, before their fans could blink their eyes, he was replaced by Winnipeg guitarists Kurt Winter and Greg Leskiw. Randy could at least take comfort in the knowledge that it took two guitarists to replace him.

He may have seen this coming, but what Randy didn’t anticipate was the backlash he got from the Winnipeg music community. He essentially got blacklisted and nobody would play with him. His publishing and record royalties ensured that he wouldn’t starve but that didn’t satisfy his creative itch and he ended up working for the CBC in Ron Halldorson’s house band for a new country music show called “My Kind of Country.” Randy had always been a country music fan, so it suited him well temporarily. One day, out in the corridors, he bumped into Chad Allan who told him he was getting ready to do some recording at Century 21 for a solo album and invited him to join him.

Like a lot of musicians in the early 1970s, Randy and Chad had both been bitten by the country rock bug. The movement began in earnest a couple years earlier when the Byrds went to Nashville and recorded a straight-up country record. They’d already been headed in that direction with a couple tracks on their 1967 “Younger Than Yesterday” and “Notorious Byrd Brothers” albums but went full on C&W when Gram Parsons was recruited to replace original member David Crosby. He’d already been blazing country rock trails with the International Submarine Band and convinced his new bandmates to make a country record in Nashville. Their 1968 Byrds LP “Sweetheart of the Rodeo” was lampooned by critics on its release but served as a template to fellow artists who listened without prejudice like Bob Dylan, Linda Ronstadt, Jerry Garcia, Rick Nelson and Randy Bachman. Randy saddled up for this new direction and was particularly buoyed by friend and fellow Winnipeg music scene alumnus Neil Young who’d brought a country sensibility to Buffalo Springfield and Crosby, Stills & Nash.

Chad was all on board with Randy’s vision and the sessions quickly morphed into a band concept once brother Robbie Bachman was brought in on drums. In a short period of time, they laid out 12 tracks and mixed them onto an acetate. Randy got a hold of Neil and played it for him, and not only did he like it, but he went an extra mile by setting up a meeting between Randy with Mo Ostin, the president of Reprise Records. Neil Young was one of the hottest things in pop music in 1971, so a recommendation from him carried a lot of weight. After a quick meeting in Los Angeles, Brave Belt was the label’s newest signee and “Brave Belt I” was released on May 25, 1971, to mostly pleasant reviews. Billboard Magazine called it solid, “but lacks the drive to hit high and hard.”

That was pretty much the verdict out on the road too. It wasn’t exactly the type of music to make people get up and dance. Randy had made the decision to not be a second-rate Guess Who and went totally uncommercial, but the dramatic about face made his new music boring in comparison. Fate did smile upon him however when, before heading out to promote the album, he hired Fred Turner of the touring pub band the D-Drifters to play bass and provide harmony vocals. Fred possessed a freight train of a voice that revved like a Harley Davidson Sportster, and it didn’t take very long for him to assert himself.

Chad had seen this movie before and on October 31st, following several sessions for their follow-up album, left Randy again with no real reason given. It seems that he just wasn’t the competitive type and didn’t feel the need to fight for his job. He was a talented singer with a pleasant voice, but Burton Cummings and Fred Turner were giants in their field. The weekend after Chad left, Brave Belt had a disastrous gig in Lakehead University’s student union cafeteria in Thunder Bay in Ontario. They carried on as a trio and played their set. By 10:30 on Friday night, they’d cleared the place out and the promoter fired them. The following morning, as they were loading up their van to head back to Winnipeg, the same promoter tracked them down and asked them to come back but asked them to play rock and roll instead. They worked up a set that included many contemporary and classic rock hits by artists like Creedence Clearwater Revival, Free and the Rolling Stones and got the place jumping. It brought out the best in Fred Turner, which led them down a new path.

Fred’s vocals rounded out the remainder of the tracks on the “Brave Belt II” album, which garnered more mixed reviews upon its release in February 1972. You couldn’t really blame the listening public. Brave Belt had given them two vastly different albums, one country rock and one harder rock, with each being led by vastly different singers. Between the lack of sales and confusion about how to market them, Reprise dropped Brave Belt in the middle of their third album sessions, but it turned out to be a blessing in disguise.

Randy had used his Guess Who royalties to finance the band to the tune of just under $100,000 and was nearly tapped out. They mixed Fred Turner’s “Gimme Your Money Please” down to a demo to shop to record companies and influential industry executives but got nothing but rejections. They were facing the inevitable end of Brave Belt when, out of the blue, Randy got a call from Charlie Fach of Mercury Records who loved we heard and made them a $100,000, two-album deal. It was an exhilarating moment and a reward for their hard work and sticking to their vision. Randy broke even from his Brave Belt experiment and, to signify a fresh start, renamed the band to Bachman-Turner-Overdrive. Less than two years later, Mercury’s gamble paid off when another Randy Bachman-written tune, “You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet” topped the pop charts in both the U.S. and Canada. They’d go on to score six U.S. Top 40 hits and 10 in Canada over the next three years, outshining the Guess Who at home and in the U.S.

Find a Place

Chad Allan eventually faded into the background completely. He put out a solo album entitled “Sequel” on the GRT label in 1973 followed by a musical version of the old English poem, “Beowulf” with an ensemble where he sang the songs of the titular character. He re-recorded “Shakin’ All Over” for K-Tel, which spurred the Greek label Seagull to release an album of the same title in 1978. After a couple of singles in the early 1980s, he went into teaching songwriting full time at Kwantlen University College in British Columbia. He released a Christian rock album in 1992 called “Zoot Suit Monologue” and would disappear from any sort of public life shortly afterward. He eventually moved to Vancouver and remarried in 1999. He didn’t participate in any shows during the Guess Who’s 1983 and 2000 reunion tours and was seemingly forgotten by his old band. He was honored with a membership in the Order of Manitoba in 2015 “for his contributions to the Canadian music industry including the pivotal role he played in the creation of two legendary Winnipeg rock bands: the Guess Who and Bachman-Turner-Overdrive.” Two years later, he suffered a debilitating stroke that contributed to his death in 2023.

It’s easy to look over Chad Allan’s career and point out missed opportunities and an almost pathological fear of success, but it seems that, for Chad, it was about lifting up others. He certainly did that with old friend Randy Bachman twice and left him to his own devices from which he did very well. Back at that Vancouver senior home in 2005, then aged 62, a woman close to his age came up to thank him for entertaining her mother and her fellow seniors.

“What for?” he asked.

“My mother hasn’t sung or laughed in a year. And today she’s singing, she’s laughing. Thank you for that.”

I try and read all of Mr. Scott Sea’s articles. I consider myself a music person / nut , and ALWAYS learn something I never knew or get more details to the lore. His writing puts you right into the storyline, like a fly on the wall. That’s what you want when you read something and I appreciate his style. I love how he weaves the background stories into what the average person may know.

Thank you again for a wonderful article.