As co-founder and electric livewire of The Move, Ace Kefford played bass with instinctive swagger and prowled the stage like a glam-rock prophet in waiting. He wasn’t the slickest singer, though his voice had guts. Wasn’t the most technical bassis, though every note hit like it counted. In the swirling chaos of late-’60s British psych-pop, Kefford was a peroxide-blond force of nature with a flair for danger and a soul stitched together with brilliance.

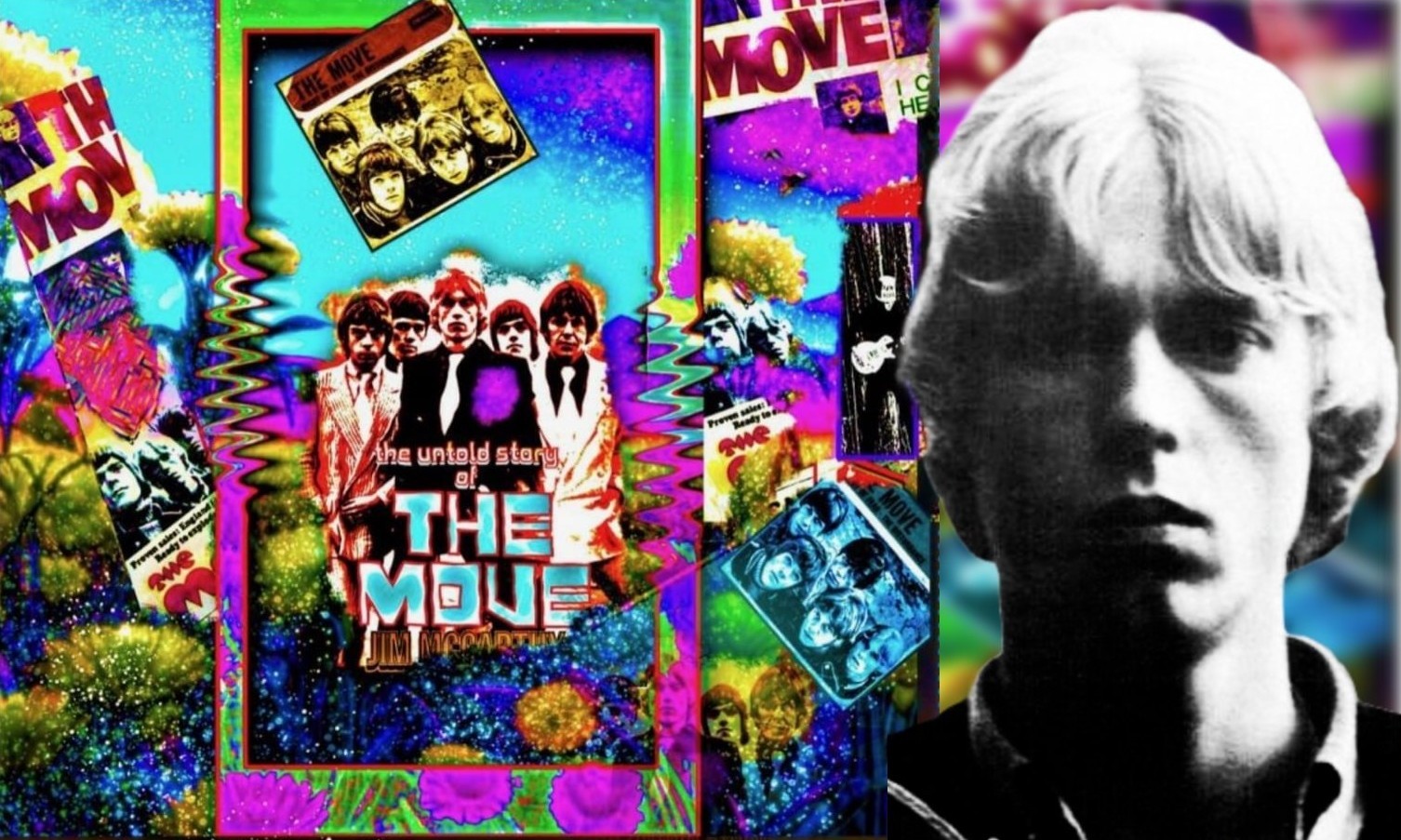

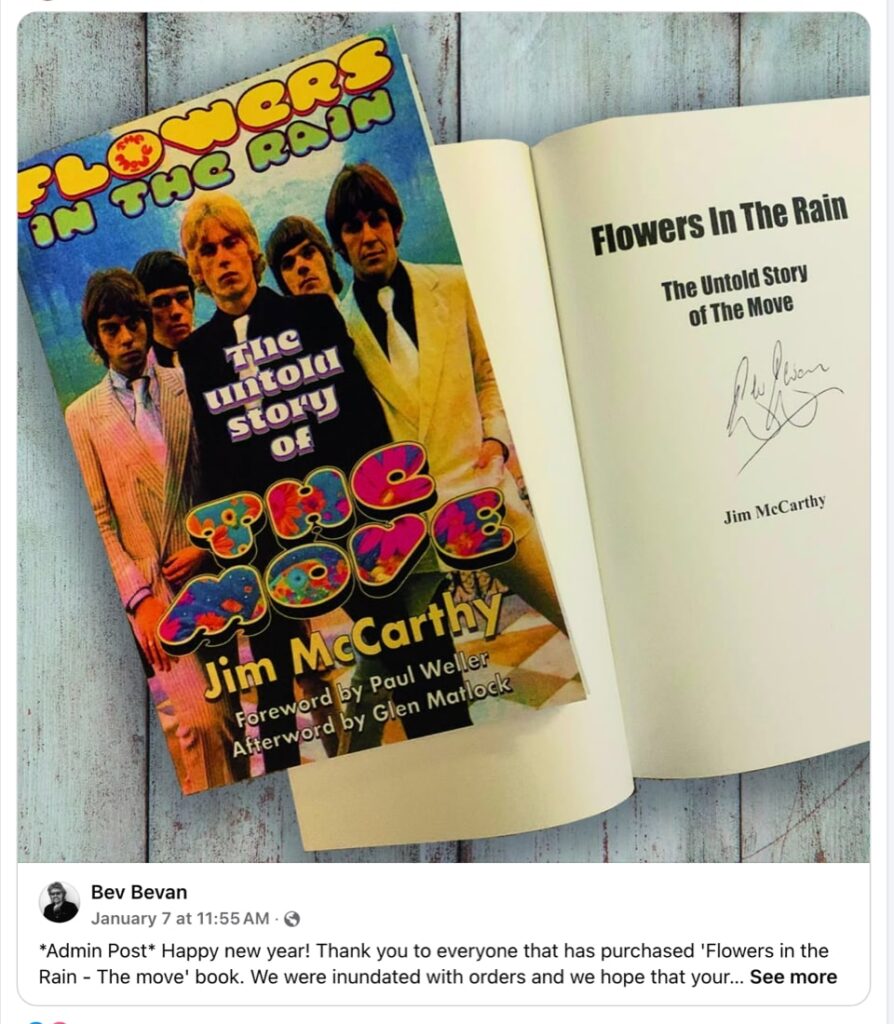

What happened next is equal parts cautionary tale and cracked mirror myth. Drugs, breakdowns, creative exiles. The stuff of liner-note footnotes and pub tales. But if the music press likes to recycle its Icarus figures, Jim McCarthy at least lets Kefford burn at full volume. This excerpt from Flowers In The Rain: The Untold Story of The Move doesn’t romanticise Kefford’s disintegration so much as give it texture: tender, and all too human.

See the people all in line, what’s making them look at me?

Ace Kefford has occupied one of those cult-like spaces in the music business archives. Every now and then in the music press over the years, you would read a suitably vague new piece. However, Alan Clayson’s 1994 piece in Record Collector revealed the turmoil and the chaos that he had still experienced, before coming to land in rehab and to live for a while in Bradford. In some ways Ace has been lumped in with Pink Floyd’s Syd Barrett and the Rolling Stone’s Brian Jones and also poor Peter Green etc. Features that also held that “loner madness” flavour.

Since his departure from The Move, Kefford has become easily the most enigmatic of the Brum Beat performers from that era. Ace’s story is much different to theirs. In the fact that he has somehow, come through all the suffering and anguish, if not all in one piece, certainly with the semblance of some peace of mind and balance. Ace learnt to cope with his mental conditions and managed to survive mental collapse, addiction and a serious mental condition. Which nowadays is recognised correctly and can be treated effectively with medications.

He is still alive and in touch with his family in a meaningful way. Ace has lived a tough life at times. However, there seems to be a ‘helping hand’ looking after him, through many years of intense difficulties. Ace paid a price that would devastate his mental health for years to come.

By the early part of 1968, Ace Kefford’s brain was extremely frazzled. He was increasingly inhabiting a very frail place. The Harold Wilson ‘Flowers In the Rain’ court case had increased his already deepening state of paranoia. He was still living on a weekly wage (as were all the members of The Move) and not pulling in any serious money. Obviously, they generated money from their relentless procession of gigs, but they were paid a wage, and the money was not paid to them from the proceeds of the gigs. Many other things were coming to a head between Ace and the other four members of The Move.

There was increasing friction in the group. Ace’s (and Trevor’s) arrogance and aggression was at a high level at that time. The entire band had increasing egos and an over-entitled attitude. Not unusual in most bands who are making it. Ace (rightly) felt that the band were ignoring his songwriting contributions — and they were! He had collapsed in the studio having a blackout or a breakdown of some description when they were recording ‘Fire Brigade’. He also became more paranoid about frenzied fans chasing him around. Trying to pull his hair out, he once got stabbed in the face, near the eye with a pair of scissors. Was that an assassination attempt or somebody trying to get a lock of his blond hair?

Ace could have certainly developed further, in the same way that Roy did. The fact that he had consumed large and constant quantities of LSD during the last few months also aggravated matters severely. This was making him much more unstable and with much less grasp on reality. Also, the taking of amphetamines (speed, uppers), over a period of time can have a very debilitating effect on mental health in terms of very erratic sleep patterns. Plus living at a very “high” rate of pumped up, mental and physical perturbation, day by day. In those less enlightened days of the 1960s it was still pretty much a time of asylums, strait jackets, men in white coats. The use of heavily sedating drugs like Thorazine, Largactil (aka liquid cosh) and the use of (ECT) electric shock treatment.

Mental health issues were generally swept under the carpets. Along with many other evil societal abusive trends. Like the seemingly huge, hidden (and ever growing) areas of child abuse etc. Whilst reading Simon Spence’s Stevie Marriott All Or Nothing book, it seemed to me, the very same symptoms and reactions, were happening to Andrew Loog Oldman (who at that time, had left the Stones management and was focused on managing The Small Faces) and very severely later on, with Steve Marriott himself.

Ace was trying to self-medicate the pressure and problems of fame, success hyperactivity disorder), possible stage fright or good old general overwhelm. Coupled with the relentless supply of energy needed to keep performing, not many people can possibly understand what this sort of pressure is like. All this was furthering Ace’s precarious mental state. Making him harder to communicate with. The other band members really began to do a number on him. In terms of sending him to Coventry. This behaviour often takes the form of pretending that the shunned person, although conspicuously present, cannot be seen or heard. For Ace in his incredibly vulnerable state, which was not helped by the constant added mixture of acid and other drugs in his system, these actions against him by the other four, would have mightily added to his increasing paranoia. Why the Move members, enacted out this cruel farrago towards him, one can only guess. It was certainly a deeply, hothouse affair: The psychology of five testosterone-filled young men, packed into the group van, playing their arses off at a very high level every night.

In those days absolutely no one at the benefit of an accrued rock culture history with hindsight from 50 years on perspective. Nobody knew how long it was all gonna last. It was put out a single or album, get out on the road and work it hard. Everybody was at their wits end after the Harold Wilson affair.

They appeared to be very jealous of the fact, Ace got the solo photo ops. He had incredible charisma and good looks. And he was very popular with the ladies. But the real tipping point was that Ace ingested a lot of home-made acid in Birmingham and all at once!

“At that time, I and another person, had bought a phial of acid. Afterwards, we went to my apartment and drank it. Of course, we did not know exactly how much we took, as it was in a bottle. In short, I went too far without knowing it. We both ended going to the Club Cedar. I was not understanding what was happening.”

Prior, Ace had gone to some students’ house in Birmingham. These stupid dopes were (think about cut-rate Oswald Owsley types) manufacturing bathtub drugs in Birmingham. They were making their own liquid LSD and Ace bought a phial from these clowns. Ace ended up necking a sizeable amount all at once. This was tantamount to a full-on mind-fuck session of psychedelic Russian Roulette. Ace and Trevor went on to The Cedar Club that night. (Remember LSD was something to be taken in microscopic pin prick doses. Or on a blotter, a sugar cube or similar. Essentially, it was to be taken in very minute doses). Ace began to experience a lot of anxiety as the trip came on. Kefford saw people dressed up as pirates (it was a fancy-dress thing going on that night).

Trevor Burton adds some detail to this troubling series of events. “Ace flipped halfway through the evening, so I put him in a cab and sent him home. He was never the same again.” The driver was instructed to drive him back to his place in Chester Road, Wylde Green, Erdington. As the trip came on and developed Ace was having to face, what was known back then, as “the horrors” or as a “bad trip.” Ace started to ‘see’ these little goblins. Little men with pointed heads all around him. This was the swirling, visual hallucinations aspect of taking LSD. These little creatures were clambering over him and talking to him. Ace shudders,

“Apparently, because in my childhood, I had a small problem understood any of this. If a panic attack happens on the road. Or if they happened during the transmission of Top Of The Pops, I was wanting to get out of there immediately. I did not understand, what was going on myself. I spent my later life in asylums for the insane, rehabilitation centres and other institutions — just to come back to where I am here and now.”

(Author note: I personally took LSD about three times. The and I felt “at one” and “communed with nature” in a local London park. But the second two times I got bored by the actual hours’ length of “the trip”. I discovered what I needed from acid. But I’m mighty glad, I didn’t suffer any adverse effects. Those came later — primarily through alcohol and other drugs).

Collectively all of this was leading towards a resentful, seething musical social situation in The Move. Which would finally burst its banks, with Ace being The Move’s first casualty. Or as Robert Davidson put it, “The blond beautiful, Chris “Ace” Kefford, who fell and became the group’s scapegoat.” At his last rehearsal, Ace made his feelings known using some direct action. He through his Fender Precision slad bass against the wall. Summarily, Ace left the rehearsal and quit The Move. Effectively, it was the last time the original five-piece played together. Sadly, this was the beginning of an eroding and twisting ending for The Move.

Ace details that last grim day for the five-piece:

“We were rehearsing in Birmingham at this village hall, and I couldn’t take any more. It wasn’t just the group. It was going out and being seen in public. How can you do Top Of The Pops if you can’t even go into a supermarket and buy something? I hadn’t thought, I was gonna leave the band before the rehearsal. The atmosphere was so bad, and I just couldn’t take it anymore. The atmosphere stunk. The band were all still fucked up about the Harold Wilson thing. But nobody was saying anything. So, I just took my bass off, smashed it against the wall and walked out. There’d been a lot of tension. I do blame people, but I was also very hard to put up with. It’s all right having great charisma and being really groovy and photogenic, but if you’re threatening everyone and they’re too scared to question you; whether my bass is in tune in case they get the fucking bass, around the head… I was mad… I phoned my missus up and said, ‘Can you take me home?’ When we got back, I pushed her out, bolted everything up. Put settees and chairs in front of the door. I got some razor blades and slashed my wrists! I ended up in hospital. I’d had enough, I didn’t wanna live any more. I’d been like that for months, hoping I was gonna feel better. But it never did get any better. It all started the night I took too much acid, man! I’d dropped loads of acid before. But I’d never swigged a bottle out like that? Screwed my life up, man. Devastated me, completely.”

John Kirkby, the road manager with The Montana’s, recalls The Move having a meeting at the Rum Runner on Broad Street, Birmingham to discuss the growing concern and disharmony about the ongoing Ace situation. There was a meeting between the band and Secunda at the offices. Apparently, this meeting did not go very swimmingly.

But from Ace’s perspective,

“Everyone was carrying on acting tough! But I think everybody was shitting themselves. A couple of weeks before that, I’ve been in the recording studios, doing the next single ‘Fire Brigade’. I just blacked out, right taking me out to get fresh air. When they all went back into the studio to continue with the session, I just fucked off — got on the train and I went home. Pull down all the screens in the passenger department, my paranoia was so heavy. Luckily, I had done all my bass parts before. Again, I had just dropped some acid. Even after overdosing on the bottle of acid just before, I still hadn’t learned my lesson.”

Ace also recorded in an interview with Ugly Things, Issue 22, published in 2004. “That was the day when I started fucking losing it. The night when I dropped all that bloody acid. I was never right after that. I was always cocky and I was very sure of got me into the bed and then she jumped out of the bed and shoooom — she shrunk down to the size of a little fucking thing. To about the size of a rabbit. I knew I had done something dangerous. When I saw all the stuff that was going on. That’s what damaged me really. I just couldn’t carry on with the band anymore, I had to leave.”

The Move’s history and Ace’s last rehearsal was remembered in a well-presented BBC Television production called Rock Family Trees in 1995. This 45-minute documentary was based on Pete Frame’s popular Rock Family Trees books. Laid out in a similar fashion as in generic family historical trees. Trevor Burton remembers the incident. “Ace went very strange for a while. He went very paranoid. It was a two- way thing. He would get in the car and go all the way to a gig. He would start talking to himself, saying ‘They’re not talking to me today.’ Everyone would be saying, ‘He’s going barmy.’ It was all the pressure, and one day at rehearsals, he threw his guitar at the wall and walked out. He went home and slashed his wrists and that’s how he left the band.”

Ace remembers this fraught time, from his point of view: “We’re driving to a gig 200 miles away and 200 miles back. And none of the other members of The Move spoke to me at all.” It was probably shared responsibility. Ace (and Trevor it must be said) was arrogant, bad tempered, and inclined to explode a lot. It put the group on their back foot all the time. They hatched a plot to ostracise him within the group and they effectively forced him out. There was quite a bit of jealousy too. In fact, Tony Secunda in later years, opined to writer Dave Thompson, “Ace was definitely the star in The Move.”

Ace had also appeared to have one incisive nervous breakdown following the intense package tour with The Jimi Hendrix Experience and Pink Floyd, which took the form of a severe panic attack. Carl Wayne believed strongly that the start of The Move’s downfall was in Ace Kefford’s departure. I totally agree. The band developed a hole that was never filled. Carl opined, “Because it placed Trevor into the vulnerable position of having to play more instruments.” It was said, the band could (possibly) have survived, if they had recruited a keyboard player to replace Kefford.

Roy Wood recalled of Kefford, “Ace left because he couldn’t handle it. Ever since the day we formed, none of us really got on very well with him. He was a very strange person. He was very aggressive, and Ace and Trevor used to have a lot of fights all of the time.” Although in a recent interview with Trevor, he told me, “Generally, me and Ace got on very well and I thought his bass playing was great.” The rankling resentments and widening cracks were starting to show after ‘Fire Brigade’.”

“As a five-piece, The Move was a magnificent band,” says Bevan, “but once Ace left – The Move were never as good again to be honest. In those early years. I’m talking 1966, ‘67 and ‘68 — The Move were brilliant. The vocal harmonies were fantastic, and we worked really hard. We were also incredibly ambitious, and we deserved what we achieved. In many ways I think we were underrated. We stayed permanently in the shadow of The Beatles and The Stones. We made the mistake, and it was a big mistake! Of just being a singles band when we should have been concentrating on albums! That was the way it was going at the time. We just kept churning out hit singles which was all well and good. But we never made a decent album really, which is a real shame.”

Carl Wayne was pragmatic: “I think it would have been interesting to see how The Move would have developed. Had we all stayed together and carried the burden — and I mean that in a kind way, of those hits. Because we would have had to compete on the same level with Hendrix, Cream, Floyd! We would have had to do the big arenas! We couldn’t have done those as a pop band. We could have developed those songs, to play them in the big arenas. My feeling is that we probably could but who knows?”