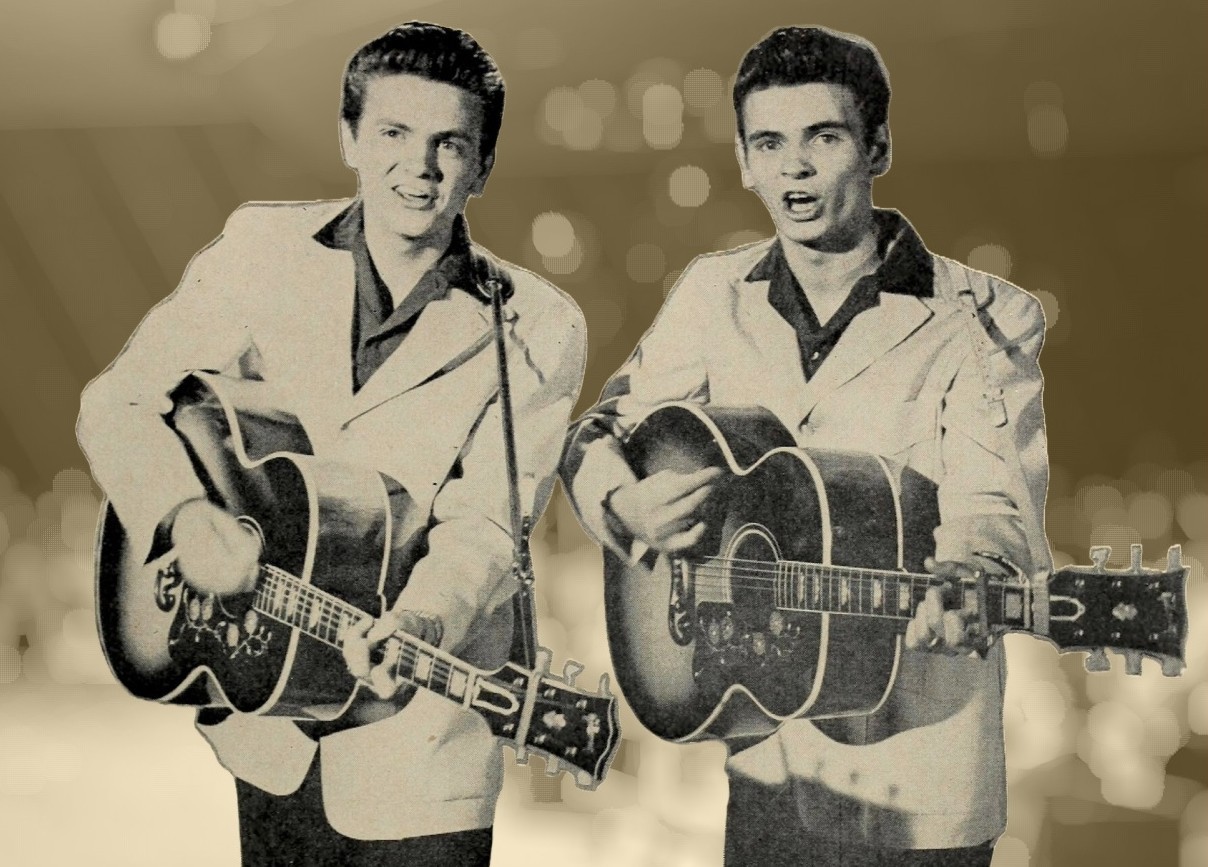

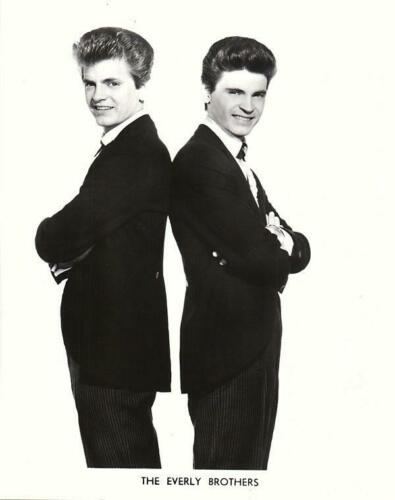

The Everly Brothers, a name that rings through the grand halls of rock and roll history with the clarity of their own immaculate harmonies. To many, Don and Phil were simply two well-coiffed young men crooning about love and heartbreak, but as Scott Shea so astutely explores, their reach extends far beyond wistful nostalgia and jukebox reveries. Indeed, their influence is woven into the very fabric of modern music.

It is a tragedy, of course, that many contemporary ears remain unacquainted with the Everlys’ magic. That once-ubiquitous blend of Appalachian roots, baroque pop, and raw, unvarnished emotion has, in some circles, been reduced to mere footnotes in the larger rock narrative. But as Shea reminds us, their legacy is not merely one of commercial success and chart triumphs, it is a tale of seismic influence, whispered in the music of the Beatles, the harmonies of Simon & Garfunkel, and the guitar sound of the Rolling Stones.

Introduction

I vividly remember listening to the Howard Stern Show on SiriusXM on January 6, 2014. The legendary comedy talk show host wraps every show up with a news segment conducted by his longtime co-host Robin Quivers and it can last anywhere from 30 minutes to two hours. In addition to all the daily news topics, it’s chock-filled with Howard’s opinions on many of the stories, side discussions, interruptions, shenanigans and calls from listeners. On this particular show, she announced the passing of legendary singer Phil Everly of the Everly Brothers a few days earlier. The 1950s brotherly rock and roll duo burst on the scene in 1957 with their Cadence Records debut “Bye Bye Love,” which hit #2 on the Pop Charts and launched a steady run of Top 10 hits that lasted about five years. After Robin’s announcement, Howard turned to another longtime cast member, Fred Norris, to get his reaction. The mostly quiet sound effects guru who joined Howard in October 1981 as a producer and engineer is the show’s resident music aficionado and an accomplished musician who’s led his own rock band for decades. Quizzically, Fred didn’t have much to offer and told Howard that he never really got into them.

I was astonished when I heard that and a touch disappointed. Like a lot of show fans, I thought highly of Fred Norris, particularly about music. His response didn’t change that, but it did surprise me a little. I thought perhaps he was just playing it cool because even though the Howard Stern Show cast is comprised mostly of people my parents’ age, in many ways it’s very much a high school atmosphere. Howard plays the part of the ultimate cool kid holding court at the corner table in the cafeteria with everybody trying to stay on his good side, and heaven forbid you tell him you enjoyed somebody who’s not current.

But I must admit, Fred’s response wasn’t abnormal. It’s been my experience that most classic rock fans, which for argument’s sake encapsulates the late-1960s through the early-to-mid 1980s, view most pre-Monterey Pop rock and roll stars as being one degree above Patti Page and Liberace. As an oldies fan who grew up in the 1980s and 90s, it’s something I’ve dealt with my entire life. But I always found it ironic and somewhat funny that many of the rock artists my friends idolized, like the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Simon & Garfunkel and others, were directly influenced by this brotherly duo from Kentucky. In fact, all of rock and roll owes a great debt to the Everly Brothers.

Million Dollar Contract

In February 1960, the Everly Brothers made national headlines when Lester Rose of Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. announced on their behalf that they had signed a 10-year contract with Warner Brothers Records worth $1 million. Actually, it was for $750,000, but their manager Wesley Rose propped it up for the press most likely to increase their appearance fees, and they were one of the first rock and roll acts to receive such a sum. To the parents who probably read the article before their kids, it surely must’ve seemed like a colossal waste of money and that a couple caterwauling, rock-and-roll singing brothers in their early 20s would gross such an outlandish sum while they eked out a living. That same outrage still exists today. But that’s not how Warner Brothers Records President Jim Conkling felt about it. This wasn’t yet the Warner Brothers of Fleetwood Mac, the Grateful Dead, Rod Stewart and Prince. The label was not yet two years old and with their biggest singing star being a toss up between Tab Hunter and Connie Stevens, one might mistake their artist roster for their latest teenage exploitation film cast. They needed to make a big splash and the Everly Brothers were it.

For the past three years, the Everly Brothers were killing it on the much smaller Cadence Records label, which was run Archie Bleyer, the orchestra leader and musical director of the immensely popular Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts variety show, which aired on both CBS television and radio. Though Cadence was based in New York, the Everly Brothers did most of their recording in RCA’s new Nashville Studios on Music Row with many of the same session players who’d played on country records by Don Gibson, Jim Reeves and Hank Snow. It paid dividends. During their three-year tenure, they racked up seven Top 10 hits, including the #1 hits “Wake Up Little Susie” and “All I Have to Do is Dream,” and the start of the new decade coincided with contract renewal time and Cadence would have to put up or shut up. Archie Bleyer chose the latter.

The Warner Brothers contract was unprecedented for the time, but it showed the growing trend toward rock and roll stars as the preferred artists for large record labels, especially when you consider that only four years earlier RCA Victor only paid $35,000 to buy out Elvis Presley’s contract from Sun Records. And although the seven-figure sum seemed outlandish to outsiders, Warner Brothers most likely made all that money back and more within a year as they kicked their tenure off with the self-written #1 hit “Cathy’s Clown” and followed that up with five of their next eight singles going Top 10, which generated around $35 million in sales.

But the tank began running empty following the April 1962 release of their single “That’s Old Fashioned (That’s the Way Love Should Be),” which would be their final entrance ever in the Top 10 and even in the Top 40 for two years. It was telegraphed months earlier after a falling out with their manager Wesley Rose who was also the president of Acuff-Rose Music. Don Everly was becoming more hands-on in the studio and desired to produce a session that featured a radical arrangement of Bing Crosby’s 1933 hit “Temptation,” which came to him in a dream. Rose hated the idea and did his best to undermine it. Don and Phil have both said his animus arose because the song wasn’t an Acuff-Rose copyright, which would reduce his profit. Rose said it was because he thought it was a career misstep for them. Nevertheless, a hard-headed Don went through with it. It did only peak at #27, but it wasn’t the instant death knell that Rose had predicted. That honor would go to what took place immediately afterwards.

In April 1961, the Everly Brothers fired Rose by telegram. It was impersonal and insulting, but it came as no surprise as he and the brothers hadn’t spoken since January. It did produce an equal and opposite reaction, however, as Rose blocked their access to the substantial Acuff-Rose music catalog and prevented Boudleaux Bryant and his wife Felice from working with them for the foreseeable future. The Bryants had not only played a pivotal role in nearly all their Cadence sessions, but they also wrote 11 of their 16 Top 40 Cadence hits. It was a gamble the Everlys were willing to take. Don and Phil had both developed as songwriters and between that and a slew of top publishing companies eager to provide them with material, they figured now was as good as any time to branch out. They topped it all off by moving to Los Angeles, which is where much of the music industry was based and began working with Aldon Music who had a successful batch of songwriting teams like Gerry Goffin and Carole King, Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil and others.

There’s no doubt that Wesley Rose could be a manipulative pain-in-the-ass, but he did successfully guide their career beginning at Cadence and signed them to this unprecedented deal with Warner Brothers. Their problem was, when they cut him loose, they never factored in the inevitable end of the gravy train. Warner Brothers may have been attached to a legendary movie company, but they were still a long way from RCA Victor and Columbia. It’s easy to understand their youthful arrogance. They were young and bold and their co-written #1 hit “Cathy’s Clown” kicked their Warner Brothers tenure off with continued chart dominance. They hit the Top 40 eight more times between 1960 and 1962 with five of those singles hitting the Top 10. But the Summer 1962 release of “Don’t Ask Me to Be Friends,” written by the husband-and-wife Aldon Music songwriting team Gerry Goffin and Carole King, only topped out at #48 and neither of them could’ve predicted the drought that followed. In fact, the charting of their ensuing releases was so bad that it took them nearly two years to jump back into the Top 100. They finally reentered the Top 40 with their 1964 release “Gone, Gone, Gone,” written by Don, which hit #31, but the struggle continued. They’d only make it to those reaches once more in 1967 when their wistfully sentimental single “Bowling Green,” written by their touring bassist Terry Slater, peaked at #40. It was clear their steady charting days were over, but it wasn’t over poor quality records. As the decade wore on and the Everly Brothers got lost in the Warner Brothers shuffle behind Peter, Paul & Mary, the Association, Van Morrison, James Taylor and others, they were forced to take on the role of rock and roll statesmen. And even though their new songs were hardly being played on the radio, the fruits of their decade-and-a-half labor began ripening in other ways.

Roots

The seismic shift that the Beatles created with “I Want to Hold Your Hand” in February 1964 changed American music scene dramatically. It led to an onslaught of British artists and almost instantaneously nearly every American artist who came before them became invisible. The public and the entertainment industry craved anything British for about a year-and-a-half and everything domestic took a backseat. Promising American groups filled with incredibly talented musicians gave themselves British-sounding names like the Golliwogs, the Mugwumps and the Beefeaters just to try and get their foot in the door (those aforementioned groups featured members of Creedence Clearwater Revival, the Mamas & the Papas, the Lovin’ Spoonful and the Byrds). They’d eventually get their opportunity when the Byrds broke through with “Mr. Tambourine Man,” but things seemed pretty bleak for a while.

Change is difficult for almost everybody and many older rock and rollers took it hard. They were once the toast of the town with producers of Ed Sullivan, American Bandstand and the Steve Allen show beating down their doors for bookings. Now, it seemed all they heard was crickets. On the outside, it seemed almost disrespectful that these new English bands came out of nowhere and stole all their thunder, but it was anything but. Most of these British Invasion bands held first generation rock and rollers in high esteem and were profoundly influence by their works. For many these youngsters from Liverpool, Manchester, London, and Newcastle upon Tyne, Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Buddy Holly and the Everly Brothers were nothing short of gods.

The Beatles were so influenced by the Everlys that they considered naming themselves the Foreverly Brothers for about five minutes before settling on their now-legendary moniker. You couldn’t tell their love by looking at the covers they recorded for their early albums and singles or at their BBC recordings, which only contains their obscure “So How Come (No One Loves Me),” but you could hear it in their harmonizing. Early songs like “Ask Me Why,” “Misery,” “All My Loving” and “All I’ve Got to Do” are very Everly Brothers-ish. While writing the arrangement for “Please Please Me,” their first big hit in England, in addition to Roy Orbison, Paul also had “Cathy’s Clown” in mind because of its big arrangement. The Everly Brothers were one of the first artists to use multiple guitarists, bassists and drummers playing in unison to create depth. The opening guitar riff in their 1960 hit cover of Little Richard’s “Lucille” features eight Nashville session guitarists playing in unison.

As the sound of the Beatles developed into its own thing and the influences of the previous decade gave way to sitars, backwards guitars and French horns, the Everly Brothers’ sound never strayed far from Paul McCartney’s heart. He and John tapped back into their love of Everly-styled harmony for “Two of Us,” the opening track of their 1970 “Let It Be” album. With Wings, he mentioned Phil and Don by name in their 1976 hit “Let ‘Em In” and he gave his beautiful “On the Wings of a Nightingale” to the Everlys for their 1984 reunion album, “EB 84,” which got them in the Top 50 for the first time in 17 years. He even played guitar on the session.

The Beatles counterpart, the Rolling Stones, got up close and personal with the Everly Brothers when they opened for them for five shows on a package tour around England in the fall of 1963. As far as their music was concerned, the five hardcore blues fans displayed little Everly influence on the surface, but Keith Richards was profoundly affected by Don Everly’s rhythm guitar playing. In his 2010 autobiography, “Life,” he called the Everly brother “one of the finest rhythm players,” and went through a decade of trial and error trying to duplicate the unique guitar sound he got on tracks like “Bye Bye Love” and “Wake Up Little Susie.”

At the dawn of the British Invasion, Keef was a far cry from the swashbuckling, Jack Sparrow-looking rock star who effortlessly played all those famous riffs with a cigarette casually dangling from his lips. He was a tough, street wise kid who grew up in the shadow of the factories in Dartford, Kent where many of the streets still contained gaping holes created by the German Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain. In the Stones’ early days, when concert promotor and future music mogul Robert Stigwood attempted to rip them off, Keith trapped him on a staircase and kneed him in the balls multiple times. He was the picture of their bad boy image, but, when it came to his instrument, he was willing to listen and learn from anyone. He didn’t learn to play his idol Jimmy Reed’s blues licks properly until Bobby Goldsboro, the saccharine vocalist whose schmaltzy death song “Honey” topped the charted while the Stones were belting out “She’s a Rainbow,” showed him how on their 1964 U.S. tour.

Four years later, he met American guitarist Ry Cooder, previously of the blues-rock group the Rising Sons, while working on the “Beggars Banquet” album in Los Angeles. He unlocked the Everly mystery for the Stone by introducing him to Open G tuning. In “Life,” he described it thusly.

“An open tuning simply means that guitar is pre-tuned to a ready-made major chord…and if you’re working the right chord, you can hear this other chord going on behind it, which actually, you’re not playing. It’s there. It defies logic.”

Ry was using it simply for slide playing, but Keith wasn’t interested in that. Brian Jones was the slide expert of the group and he desired more. He wanted to capture that Don Everly sound and use it his own way, so he simply removed the bottom string and used the A-string as the bottom note. A new world opened up to him and it’s heard in nearly everything that came afterward, most notably “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” “Brown Sugar,” “Gimme Shelter” and “Honky Tonk Women.” There are even some whispers and rumors that Keef copped the riff of the last one from Ry, but it’s never been substantiated. The music world is rife with stories of one artist ripping another off.

A little less than a decade earlier, two Manchester teenagers, Graham Nash and Allan Clarke, formed a singing duo after hearing “Bye Bye Love” reverberate throughout a grand Catholic school basement at a rival school dance. It was newly released in England and the two friends scoured every record store in town until they got caught up on all their records and created a set list based solely around them. A couple of years later, after seeing the brothers perform at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, they staked out the entrance of the Midland Hotel and approached the Everly Brothers as they walked imperviously towards it. A couple hours had passed since their final number, and it was obvious by their light staggering that they’d been to a pub or nightclub. They introduced themselves as Graham and Allan, and, to their astonishment, the Everlys engaged their two teenager fans, but it was far from heady.

“We don’t want to bother you,” he said. “We sing together. We sing like you- we copy your style.”

You could almost feel the dryness of their throats as they spoke reverently to two guys who weren’t much older than them, but the Everly Brothers were very kind to them, and it left an impression on Graham Nash who always took time to speak with fans who engaged him because of this moment. I speak from personal experience. After a couple more minutes of idle fan-star chatter, the two brothers disengaged and headed inside. Phil turned to them and said, “Hey Graham and Allan, keep it up. Things’ll happen.” That put them over the moon. They missed the last departing bus and walked the nine miles home through the chilly April night, their joy shielding them from the cold.

And things did happen. They began performing local clubs as Ricky and Dane Young until teaming up with a local band called the Deltas. In December 1962, they renamed themselves the Hollies, after Buddy Holly, and played the Cavern Club in Liverpool. They experienced a fair amount of turnover before forming the steady lineup of guitarist Tony Hicks, drummer Bobby Elliott and bassist Eric Haydock (who was replaced by Bernie Calvert in 1966). In April 1963, three years removed from their encounter with the Everly Brothers, the Hollies signed with EMI, the same label as the Beatles, and hit the UK Top 25 with their first release, “(Ain’t That) Just Like Me.” Nearly two-and-a-half years later, they cracked the U.S. Top 40 with “Look Through Any Window,” which kicked the doors open and made them a steady chart feature for the next nine years.

In May 1966, Graham and Allan received the greatest honor of their careers thus far when eight of their songs, co-written with Tony Hicks, were recorded by the Everly Brothers for their July release, “Two Yanks in England.” The sessions were booked quickly, and although the Hollies didn’t participate in them, they were on hand. Those honors went to a handful of seasoned young session musicians, including guitarist Jimmy Page, bassist John Paul Jones, otherwise known as one half of Led Zeppelin, pianist Reginald Dwight, who would soon adopt the nom de plum “Elton John,” drummer Andy White and a few others.

Although Graham and Allan emulated the Everly Brothers, they never really sounded very close to them. You can’t drop a needle on a Hollies record, close your eyes and hear the second coming of Don and Phil, but they did forge their own unique fingerprint on pop music history. Graham would better recreate that type of lilting Everly Brothers harmony with American singer David Crosby after leaving the Hollies in 1968. David was also an Everly Brothers freak and an ex-Byrd blessed with a reedy and quivering high tenor that soared to the same realms as Phil’s and complimented Graham’s light tenor beautifully. Along with ex-Buffalo Springfield singer/guitarist Stephen Stills, they formed the vocal trio Crosby, Stills & Nash and were joined a few months later by Stephen’s former bandmate Neil Young. Graham and David approached every session on which they sang harmony with the brothers in mind.

Harder U.K. acts were also drawn to the exquisite harmonies of the Everly Brothers. The Who, part of the second wave of British Invasion stars, often performed the Everly’s original 1965 B-side “Man with Money” live and on the BBC and even recorded a version for their late-1966 sophomore LP “A Quick One,” which was confined to the vaults for close to 20 years. The hard-rocking Scottish band Nazareth hit the Top 10 in the U.S. with the Boudleaux Bryant song “Love Hurts” in 1974 which was first recorded by the Everlys in 1960.

The influence of the Everly Brothers wasn’t exclusive to the United Kingdom. A couple of popular mid-1960s folk artists, Bob Dylan and Simon & Garfunkel, were big fans who performed and recorded Everly Brothers songs during their respective careers. The harmony of the latter can clearly be pinpointed to the Everlys. A live version of “Bye Bye Love” was the penultimate song on their final LP, “Bridge Over Troubled Water” in 1970 and they performed “Wake Up Little Susie” at their grand Central Park reunion concert in 1982, which appeared on the subsequent album. In the late-1960s, with the country-rock movement kicking into high gear, the harmony between Flying Burrito Brothers’ founders Gram Parsons and Chris Hillman was perhaps as close as any to the real thing. You can hear it in songs like “Christine’s Tune,” “Sin City” and “The Dark End of the Street” from their debut masterpiece LP “The Gilded Palace of Sin.” When Keith Richards and Gram Parsons got together during the Rolling Stones’ legendary “Exile on Main St.” sessions at Villa Nellcôte in the South of France, the Everly Brothers’ “Roots” album was often spun during conversations and down time. In his very short post-Burritos career, Parsons recorded three Everly Brothers tunes and would recreate their harmony more closely in concert after teaming up with a very young Emmylou Harris before his untimely death in 1973.

More straightforward country stars also found success dipping into the Everly Brothers’ back catalog. Glen Campbell and Bobbie Gentry hit the charts with duets of “Let It Be Me” and “All I Have to Do is Dream” in 1969 and 1970, respectively. Hank Williams Jr. teamed up with Lois Johnson with a remake of their 1960 hit “So Sad (To Watch Good Love Go Bad),” which hit #12 on the C&W and ex-Stone Poneys lead singer Linda Ronstadt brought the Everly Brothers back to the top of the charts with her 1975 version of Phil’s “When Will I Be Loved.” In true Everly Brothers style, she topped both the Pop and C&W charts. Actually, it only peaked at #2 on the Pop Charts, but that’s close enough.

Chained To A Memory

As the seeds of their earlier work were sprouting in the classic rock music movement, the Everly Brothers could never quite regain their footing on the charts. Their time at Warner Brothers was not fruitful monetarily in the U.S. after 1962, but it wasn’t because they made bad records. Quite the contrary. Although their decade on that label never quite recaptured the magic of their Cadence recordings, most of their releases were first rate; from the baroque chamber poppy “Nancy’s Minuet,” inspired by Henry Mancini’s score to the 1962 Blake Edwards film “Experiment in Terror,” to their hard-rocking 1965 take on Mickey & Sylvia’s “Love is Strange,” to their 1968 landmark country-rock LP, “Roots,” nearly every release was thoughtful, deliberate, well-produced and downright beautiful.

They released their last Warner Brothers single, a cover of Scott McKenzie’s “Yves,” produced by Lou Adler, on September 12, 1970, and didn’t resurface on record until nearly two years later when they signed with RCA Victor. In between, they had a brief stint as the summer replacement for the Johnny Cash Show that didn’t result in a series and made their living touring. All the adulation they were receiving from contemporary rock acts was nice, but while many of those artists were headlining festivals and playing auditoriums, the Everlys were playing mostly state fairs, amusement parks and small clubs. It all came to a crashing end on July 14, 1973, at Knott’s Berry Farm theme park in Anaheim, California where they were scheduled to perform for three nights. Halfway through the first night’s set, the park’s entertainment director pulled the plug because Don had shown up drunk and was “giving an erratic, below par performance.” It wasn’t anything new. Don had struggled with addiction since the early 1960s and was habitually pushing the envelope in his relationship with managers, promoters and even his brother. Back in September 1963, Don’s amphetamine addiction led to a nervous breakdown in the middle of their tour of England. The same demons returned a little less than 10 years later. A fed-up Phil tossed his guitar to the ground and stormed off, leaving Don to finish the stand alone and said things like “the Everly Brothers died 10 years ago” and “I’m tired of being an Everly Brother.” It would be a decade before they spoke to one another again.

Walk Right Back

In terms of their career, the Everly Brothers always felt they had to prove themselves and each single was approached with a do or die mentality. Perhaps it had something to do with coming into a scene already established by talented competitors like Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Chuck Berry and Fats Domino. Between themselves, there was equal tension. Despite reports by fan magazines and newspapers, the two weren’t very close after their career started, but nobody outside their very inner circles could say why and the secret went to their graves. Don and Phil were the only children of Ike and Margaret Everly, a singing family who hosted long-running shows on KMA and KFNF in Iowa in the 1940s then appeared regularly on Knoxville, Tennessee businessman Cas Walker’s WROL radio show after moving there in the early 1950s. Ike was an incredibly talented guitarist who passed his style along to his sons and played often with the likes of Merle Travis, Joe Maphis and Chet Atkins. There was always a competition to please dad, and many have speculated that the source of the brothers’ feud was over which one he loved best. Politics was also in the mix with Don being very liberal and Phil being a conservative.

Nevertheless, on September 23, 1983, the Everly Brothers reunited on stage at the Royal Albert Hall in London, England that was praised by critics everywhere and filmed for release on VHS and on records and cassettes. I remember seeing the commercial play for years on American television. In the subsequent two decades recording and performing together again, their past conflicts always lingered beneath the surface and would boil up from time to time, but never reached the apex that it did at Knott’s Berry Farm. They signed with Mercury Records in 1984 and issued three marvelous albums over four years and toured regularly. They recorded their final song together in 1998, a version of Andrew Lloyd Webber and Jim Steinman’s “Cold,” from the musical “Whistle Down the Wind” and gave their last big in person hurrah sharing a double bill with Simon & Garfunkel on the “Old Friends” reunion tour in 2003 and 2004. A year later, they played together for the final time at the Regent Theater in Ipswich, England.

Phil Everly passed away at the age of 74 on January 3, 2014, as a result of COPD. Don died on August 21, 2021, age 84, and the cause was never officially released, but sources say it was from a heart attack. Four months later, their mother Margaret passed away at age 102 and their father Ike died back in 1975 from complications brought on by lung cancer. He’d worked in the Kentucky coal mines as a teenager and Don and Phil always said he developed black lung.

Today, we have very few of the early rock and rollers left and younger generations are becoming more and more detached from their valuable contributions. I believe that people like Fred Norris and even Howard Stern understand them and admire the music of the Everly Brothers and their contemporaries. A lot of music people do. In fact, 2013, which still doesn’t seem like that long ago, was a big year for Everly Brothers tribute albums. Green Day lead singer Billie Jo Armstrong teamed up with the talented Norah Jones to recreate the Everly Brothers’ folk recordings from the late-1950s for an album called “Foreverly.” It was a marvelous tribute that matched their vocal blend beautifully. Earlier in the year, Dawn McCarthy of Faun Fables teamed up with Bonnie “Prince” Billy for an eclectic collection of Everly Brothers covers entitled “What the Brothers Sang.” And that spring, the Chapin Sisters, Abigail and Lily, nieces of legendary singer Harry Chapin, issued “A Date with the Everly Brothers,” which featured 13 Everly covers that focused heavily on their Cadence and early Warner Brothers repertoire. We can only hope and pray that the next generation of young singers find some inspiration in the dynamic brotherly duo.

Great to read such a near-definitive history of the Everleys! I would like to put on record the late great Philip Donnelly’s vital role in bringing them back together when he spent a semester in Nashville. Without Philip I don’t know if it would have happened. I saw them that time in the RDS in Dublin- and they played with another dearly departed musician – the great Liam O’Flynn on uilllean pipes. Unforgettable