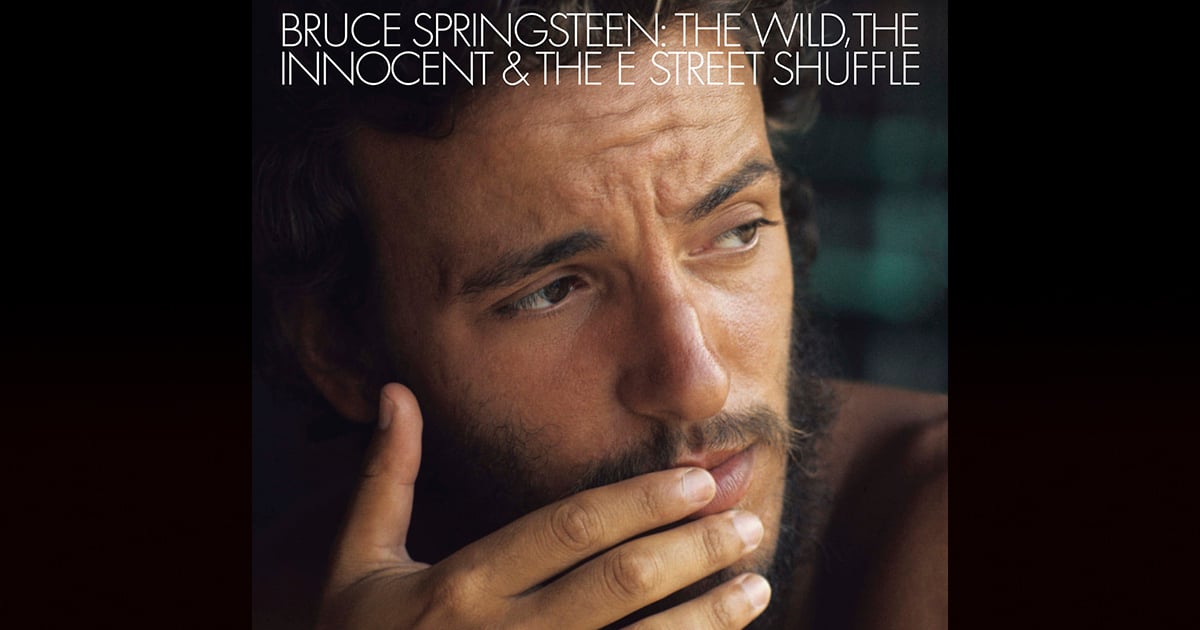

What’s Bruce Springsteen’s Most Important Album? Why, His Second One, of Course!

By Scott Shea

On June 26, 1993, I was standing at the platform of the Metuchen New Jersey Transit station with my friend Carmello. We were waiting on a train to take us into New York Penn Station to see Bruce Springsteen live at Madison Square Garden. It was a benefit show for the Kristen Ann Carr Fund to fight sarcoma and I scored free tickets from my uncle who couldn’t go. It was my second time getting to see him, Carmello’s first and our excitement was palpable. We were high school juniors and wore our emotions on our sleeves. I don’t remember if we were wearing Springsteen t-shirts but a middle-aged woman who was also going to the show recognized us as Bruce fans struck up a conversation. Outside of lamenting the breakup of the E Street Band, the only thing I remember was her asking each of us what our favorite song was. I immediately shouted, “Downbound Train,” a deep cut from “Born in the U.S.A.” I don’t remember Carmello’s answer, but it too was something recent. She kind of balked and sneered a little bit.

“Oh, you must be new Springsteen fans,” she said somewhat dismissively.

I knew immediately what she meant. Over the course of my high school tenure, I’d been developing as a Bruce Springsteen superfan and, like all superstars, there’s always an emphasis on their earlier material. It’s like that with all of them; Neil Young, Van Morrison, Tom Petty, Bob Dylan, you name it. I quickly blurted out that my second favorite Springsteen song was “Incident on 57th Street,” the leadoff track from side two of his second album, “The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle,” but she’d already tuned me out. I knew right then and there that if I was to become a true Springsteenphile, I was going to have to do a deeper dive into that part of his career and began doing just that. I wore out the “Wild & Innocent” cassette my friend Ed gave to me back in my freshman year and reexamined the earlier songs on “Live 1975/85.” I went to record shows and bought bootlegs of first and second album outtakes and publishing demos. I sought out every live show I could get my hands on from 1970s and marveled out the restructured arrangements of songs from his first two albums on subsequent tours and read up on all his pre-E Street bands. What I came away with, and believe to this very day, is that Bruce Springsteen’s second album was his most defining and important album of his long career.

I know that’s an audacious statement that’s usually reserved for “Born to Run,” but I feel an accurate one. Over more than 50 years making music, Bruce has released a lot of important albums. “Born to Run” broke him into the mainstream and saved him from getting drop by Columbia Records. “Darkness on the Edge of Town” reintroduced him to audiences after three long years of no new material because of a protracted legal battle with his first manager. “Born in the U.S.A.” was the long-awaited hit-packed frenzy and what should’ve been his logical follow-up to “The River” album instead of the folky “Nebraska.” But I contend that none of that would’ve happened without “The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle.” It was a breakout record that was criminally ignored by his record label and merged the veteran Asbury Park rock and roll bandleader version of Bruce with the Columbia Records singer/songwriter one that critics began referring to as the “New Dylan.”

Greetings!

Bruce Springsteen has always embraced the Italian portion of his heritage, so it’s only fitting that I channel the Golden Girls’ Sophia Petrillo by starting off with… “Picture it, Asbury Park, New Jersey, January 5, 1973.” Bruce Springsteen’s debut album, “Greetings from Asbury Park, NJ,” is released on Columbia Records to a resounding thud. Nobody outside his circle even realized it and the ones who did were left scratching their heads. This didn’t sound like the Bruce Springsteen they saw killing it on bar stages and clubs along the Jersey Shore the last six years. It sounded a little softer and more muted than the rocking tunes he blasted out at clubs like the Student Prince and the Sunshine In and on the campus of Monmouth College. Where was the guitar? And what’s with these wordy songs? Over time, many of them would become some of his most beloved, but in the moment, it wasn’t what his relatively small band of fans were expecting. Something was missing.

Bruce started playing professionally in 1966 with a group of high school kids from Freehold called the Castiles. They occasionally played Asbury Park, 17 miles to the east, but spent more time at the Café Wha? in Greenwich Village, the Le Teendevous in Shrewsbury, New Jersey and various clubs in neighboring Long Branch and further north in Middletown. After their August 1968 breakup, Bruce formed a power trio-turned-quintet he called Earth, but it only lasted six months. Around that time, nearly every young musician in the greater Asbury Park area, began flocking to a new underage club on Cookman Avenue called Upstage. Bruce regularly made his way to its stage on open mic nights to perform solo and dazzle patrons with his guitar playing. After impressing three other 19-year-old musicians, drummer Vini Lopez, keyboardist Danny Federici and bassist Vinnie Roslin, the new quartet of friends formed a new band in February 1969 called Child, which they later changed to Steel Mill. In March 1970, Roslin was replaced by Bruce’s old friend, Steve Van Zandt, making it the first real E Street Band prototype. The two first met four years earlier when the Castiles shared the bill with Van Zandt’s Shadows at the Surf ‘n’ See Club in Sea Bright.

Steel Mill bore all the earmarks of an early-1970s heavy East Coast psychedelic jam band in sync with what Vanilla Fudge and Iron Butterfly were doing and they built up a respectful following opening for an array of popular artists who played along the Jersey Shore, including Chicago, Roy Orbison and Black Sabbath. On a West Coast jaunt shortly before Roslin departed, they even impressed legendary San Francisco promoter Bill Graham enough for him to record a three-song demo. When he only offered them a contract worth a paltry $1,000 advance, they rejected it and headed back to Jersey. Bruce’s songs showed potential, but his style was raw, and his lyrics tended to meander and go several verses too long, but he knew he was more valuable than that. Maturity and repetition would help him hone his craft.

After Steel Mill disbanded in January 1971, Bruce bounced around the Jersey Shore club scene, soaking up the sounds like a sponge, sharpening his songwriting skills and forming friendships with musicians that would serve him well down the road. He often played open mics at Upstage or the Student Prince less than a mile away on Kingsley Street and either joined or put together fly-by-night bands like the Sundance Blues Band or Dr. Zoom & the Sonic Boom with Steve Van Zandt. In July 1971, Bruce organized his most ambitious project yet, the 10-piece Bruce Springsteen Band that featured Van Zandt, now on guitar, Steel Mill drummer Vini Lopez and a couple of newbies. Bassist Garry Tallent came from nearby Neptune City and had played in Bruce’s short-lived band, the Friendly Enemies, and with Van Zandt in the Big Bad Bobby Williams Band. 18-year-old keyboardist David Sancious was another alumnus of both bands and a coveted virtuosic piano player. The rest of the band was rounded out by a rotating cast of brass and female backing singers.

It was during the tenure of the Bruce Springsteen Band that Bruce’s musical fingerprint began to form. He was still writing long Steel Mill-ish jams, but they were augmented by shorter, more soulful numbers like “Down in Mexico” and “I Just Can’t Change” that showed the profound influence that contemporary artist Van Morrison had on his arrangements, especially after having seen him play during his pre-Caledonia Soul Orchestra period. Bruce had been a fan of the Irish singer’s 1960s band Them and his 1968 sophomore solo masterpiece, “Astral Weeks.” By 1971, Morrison had developed a gritty R&B-influenced, brass-laden style displayed on albums “Moondance” and “His Band and the Street Choir,” and they served as a template for the young Asbury Park artist. All this was serving to make Bruce’s sound more aesthetically pleasing and commercial.

Big Advance

Come July 1972, Bruce had grown weary of his big band and its wayward direction. Though he was the leader, his approach was very much benign and managing the range of disparate personalities was stressful. He’d already retreated from them back before Christmas to go visit his parents’ new home in San Mateo, California but came back a month later. Unbeknownst to everyone except his manager Carl “Tinker” West, Bruce began contemplating an exit strategy after signing a contract with manager Mike Appel. In May, he’d successfully auditioned for Columbia Records’ John Hammond who signed him to the label as a solo artist. Label executives believed they’d signed a singer in the mold of James Taylor, Tim Buckley or Tom Rush, and, for a while, Bruce did too. After disbanding the Bruce Springsteen Band, he spent the months of August and September playing alone at Max’s Kansas City and other Greenwich Clubs and hanging out with fellow solo artists, Jackson Browne, Bonnie Raitt and David Blue. In between, he recorded a batch of new songs that made up his solo debut “Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J,” several of which featured an amalgam of ex-Steel Mill and Bruce Springsteen Band players supporting him.

“Greetings” is now a beloved album loaded with Bruce Springsteen classics and a fitting entre into a legendary discography, but it was not representative of the foundation he’d been laying for the past six years. It was something Bruce would look to rectify as the sessions for his second album began in May 1973. The groundwork, however, was laid in October 1972 as Bruce began touring in support of his debut record with his new band that featured Steel Mill veterans Danny Federici on keyboards and Vini Lopez on drums, Bruce Springsteen Band bassist Garry Tallent and saxophonist Clarence Clemons of the Asbury Park band Norman Seldin & the Joyful Noyze. The tall, muscular, black ex-college football player, who Bruce first met at the Student Prince a year earlier, was brought in for the final “Greetings” sessions, which featured the more commercial songs “Blinded By the Light” and “Spirit in the Night. He took a different tact with this core of musicians this time around. Bruce was the boss and whatever he said was to be obeyed. If not, they had to deal with Clarence. Over the winter and spring, songs like “Does This Bus Stop at 82nd Street,” “It’s Hard to Be a Saint in the City” and “Spirit in the Night” were given more rhythmic and soulful live arrangements with dashes of funk and punk that made Bruce sound more like the New Ziggy Stardust than the New Dylan. New rockers like “Santa Ana,” “Tokyo” and “Thundercrack,” a dance ballad about his girlfriend Diane Lozito, were added to the setlist and really shook things up. It was time to take this rekindled energy into the studio and make his sophomore record a deliberate full band effort.

Tracks

The sessions for the second album began in May 1973 and lasted a little over four months, squeezing a day or two of recording in between an endless stream of live shows that covered mostly the Eastern seaboard and a few Midwestern venues. Bruce brought about a dozen new songs to Brooks Arthur’s thrifty 914 Sound Recording Studio in Blauvelt, New York although, because of their length, he knew he could only pick a handful. In Steel Mill and the Bruce Springsteen Band, Bruce wrote several long, epic jams that could last anywhere from 10 minutes to a half an hour. Over the last year-and-a-half, he’d become a much-improved song crafter, paring them down and telling stories that moved and kept the listener on the dancefloor shaking and the wallflowers engaged. As the sessions progressed, the concept for the album took shape and it became much easier for Bruce to determine which ones made the cut. The second record would be a travelogue of sorts, taking the listener on a ride from dingy Jersey Shore towns, into the New York City ghettos and down to the Great White Way.

The Circuit, which looped through Asbury Park and points south, was the focal point of the Jersey Shore portion of the album, which kicked off with the dance number, “The E Street Shuffle.” It was the funkiest Bruce and his band, which now included Sancious on piano, would ever get. Set to a “Monkey Time” groove, Garry Tallent’s bass, supplemented with a wah pedal, took center stage for the dance song about getting through another sweaty summer day on E Street, hence “the shuffle.” E Street was the thoroughfare Sancious’ mother lived on in Belmar and would eventually become the name of this motley band of Asbury Park musicians. In the moment, however, it signified their youthful back-alley Jersey Shore culture.

“4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy),” was a sort of lament of Bruce’s lost innocence encapsulated by the deterioration of his adopted hometown following the race riots three years earlier, which coincidentally began on July 4th. They’d been brought on by several resorts’ segregated hiring practices that gradually boiled over into civil unrest. Asbury Park was still a resort town in those days, but, in a post-Civil Rights Act society, many of the local hotels and clubs overlooked the large local black population for seasonal work in favor of white kids from neighboring towns. Six days of rioting, looting and destruction resulted in over $5.5 million worth of damages, and, though it inspired Bruce to write the song, it was mostly about lost love. The song’s antagonist, Sandy, was a combination of several girlfriends he’d known over the years, including Diane, and was reminiscent of Van Morrison’s “Astral Weeks’” piece de resistance, “Madame George.” It even included a madame of his own, Asbury Park boardwalk psychic Madame Marie Costello who was arrested in 1967 for telling fortunes in the back room of her son’s handwriting analysis storefront on the boardwalk. It’s still illegal, by the way.

“Kitty’s Back” is another character-driven number, much like “The E Street Shuffle,” but takes place in the seedier shore slums and gives us our first glimpse of the rough parts of New York City. It tells a romantic story of love, betrayal and heartache with a title inspired by the marquee of the adult Sportsmen’s Club outside of Neptune, New Jersey that announced the return of one of its most popular dancers. For the arrangement, Bruce reached back to his old Steel Mill number, “Garden State Parkway Blues,” which often got stretched out for 30 minutes. Bruce plucked its best chord changes and progressions and paired it down to just over seven minutes, making it sort of a de facto tribute to his old band. The song showcased each band member, with a rhythm section that feels its way through the song more than plays. Danny’s signature organ weaves its way in, out, over and around, and David Sancious cuts loose with a long piano solo that shows off why Bruce made room for two keyboardists. Clarence Clemons adds the exclamation point with a rusty, King Curtis-style sax solo followed by a plucky guitar solo by Bruce himself.

“Wild Billy’s Circus Story” is the folksiest song on the album. It vividly takes the listener through a day with the traveling circus, which once upon a time was a staple of Western European and American culture but was falling out of favor in a mass media culture. It’s a song that Bruce had been kicking around since the “Greetings” sessions and had been performing regularly under the title “Circus Song.” Every summer growing up, he and his family were regular spectators at the Clyde Beatty-Cole Bros. circus that came through Freehold and other small northeastern towns. Bruce fashioned a dark comedy around his memories and provided a plethora of heroes and villains, including Missy Bimbo, the Flying Zambinis, the circus boy, Sampson the Strong Man and a nefarious ringmaster.

The Big Three that make up the album’s second side features another vast array of characters, beginning with Spanish Johnny, a roughed-up wannabe gigolo, and his escapade with the young and joyfully naive Puerto Rican Jane in “Incident on 57th Street.” It was the final song recorded for the album, told completely from an observer’s perspective and is an early example of one of Bruce Springsteen’s favorite lyrical themes – redemption. Both parties enjoy their summer rendezvous, which ends rather ambiguously and leaves it up to the listener to decide whether it’s the beginning of a romance or just a hook up. Bruce’s arrangement is first rate and, through the years, would become one whose opening piano chords caused crowds to erupt. David Sancious does some of his finest piano work with the band and elicits Bruce’s love of the instrument’s high notes.

“Rosalita (Come Out Tonight)” was Bruce Springsteen’s first bonafide classic and, though never released as a single in the U.S., it received substantial FM radio play and probably should’ve been. The part-fantastic, part-autobiographical song was designed to be a showstopper and was another one inspired by Diane Lozito. Her grandmother’s name was Rosa Lozito (pronounced “Lo-zita”). The song came out of the gate like a greyhound and moved like nothing he’d ever written. It tells the story of their heated young romance and the external forces, like family, friends and work, that complicate it. Throughout 1973, Bruce and the band opened for several first-rate rock and roll artists, including Chicago, Lou Reed, Blood, Sweat & Tears and Dr. Hook & the Medicine Show, and he set out to write blistering, bold rock and roll dancers that would get people out of their seats, take their breath away and leave them as fans. “Thundercrack” and “Rosalita (Come Out Tonight)” were prime examples of that, and both competed for space on the second album. The latter won out.

The album’s closer, “New York City Serenade,” was his grandest yet; a tour de force that took listeners into the heart of Manhattan with Diamond Jackie and Billy and other incidental characters. The lyrics don’t formulate a complete story and are rather enigmatic, much like Neil Young’s “Cowgirl in the Sand” or “Down By the River,” and serve to set the mood and stimulate mental visions rather than lay out a storyline. Like “Wild Billy’s Circus Story,” it’s one of the oldest songs on the album, first played live as “New York Song” at the Main Point outside of Philadelphia in early January 1973, right around the time “Greetings” was being released. It became “New York City Serenade” when he merged lyrics from another original, “Vibes Man,” and brought in David Sancious to help arrange it and craft the beautiful grand piano prelude, which featured him strumming the piano strings with a guitar pick. Childhood friend Richard Blackwell provided the congas.

War and Roses

When Bruce and his manager Mike Appel submitted the album for Columbia’s approval, it was summarily rejected. Gone were champions John Hammond and Clive Davis, replaced by Charles Koppelman and Goddard Lieberson, respectively. Koppelman oversaw many of the pop acts and he wasn’t bowled over by Bruce’s band’s performance on the tracks, telling him he needed to recut them with professional studio musicians. He also advised that they be shortened. It wasn’t going to happen. Bruce was proud of his work and refused to change anything. He stood his ground, with support from Mike, which summarily put them in Koppelman’s crosshairs. Rather than promote their diamond in the rough, they iced him out and gave the album strained distribution and next-to-no promotion upon its release on November 5th. They even went so far as to urge radio stations not to play the record with the crazy title that came from a combination of the 1959 Audie Murphy movie and the opening track. It was now up to Bruce and Mike to get to work, so the band hit the road, surviving on a miniscule per diem and often rolling into each town on fumes. It was them against the world. When Bruce and the band performed at Fat City in Seaside Heights, New Jersey, where a bunch of Columbia executives had come to see one of the opening groups perform but walked out when Bruce and his band stepped on stage, the war was on. Each received a lump of coal for Christmas, courtesy of Mike Appel.

Although the label’s actions seem cold and perplexing in retrospect, it was the fuel Bruce needed, which is why “The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle” is his most important album. Though he may not have known it at the time, Bruce drew the line and dared Columbia to cross it. In less than a year, he’d grown as an artist, supercharged his sound with his band and grew his fanbase. Even Mike Appel didn’t believe him back in late 1972 when he told him he was more of a band guy. Many of the label’s executives believed they’d signed the next James Taylor and perhaps some felt bamboozled. But he wanted to be the first Bruce Springsteen and set out to forge his own path. Damn the torpedos!

The powerful nature of his new songs caused Bruce to continue to revisit live arrangements of his older songs and to continue the progression with his new ones. He began writing songs for his next album although the fate of that was uncertain. The stress and struggle for acceptance by Columbia gave Bruce and his band a sense of purpose, but it didn’t keep him from questioning himself. He had his vision and drive, but perhaps his stubbornness had put him and his friends at risk. After months of freezing Bruce and Mike out, Koppelman extended an olive branch by giving his stubborn new artist one more chance at a single release and that’s how the children of the second album, “Born to Run” and “Jungleland” came to be. The band grew more confident and accomplished, took on a bigger role and became an extension of its leader. In May 1974, Bruce officially christened them “The E Street Band” and they became permanently linked. A few months later, Roy Bittan replaced David Sancious and Max Weinberg replaced Ernest “Boom” Carter, who’d replaced Vini Lopez, and never left. Steve Van Zandt rejoined a year later and, for the next 33 years, the band only had two major personnel changes. After hearing “Born to Run,” Columbia gave the green light for a full album and Bruce’s creativity had hit its stride, causing Koppelman and others to pat themselves on the back for deciding to hold on to their struggling artist.

The success of “Born to Run,” and its eight powerful songs owe their existence to bold steps Bruce took with his second album. With the first album, Bruce played the label’s game and gave them what they wanted; a soft album more akin to the popular singer/songwriter movement. But he’d been in a solo mindset since signing with Appel and was more than willing to oblige, even though, against his better judgment, he took out his electric guitar. With “Wild & Innocent,” Bruce went full band and reached back to his Steel Mill and Bruce Springsteen Band days, took their best elements, trimmed the fat, fine-tuned them and brought his listeners into the world in which he’d been living for the better part of 10 years. All these years later, it serves as a Springsteen time capsule unlike any other.

Fade Away

Live performing has always been the bedrock of Bruce Springsteen’s musical career and he put more into it than the average artist. But, as the years rolled on and Bruce’s catalog grew, his older songs took a backseat and, one by one, each got replaced by his shorter, fresher songs. By the time of the River tour in 1980, only “Rosalita” was played nightly and a few others made cameo appearances. On the Tunnel of Love Express Tour in 1988, even that classic was relegated to part-time performance and all the other songs from his first two albums were effectively retired. After the Human Rights Now tour concluded in October 1988, Bruce broke up the E Street Band for more than 10 years and, for old fans and buffs, it seems they’d never hear a live performance of a song released in 1973 again. Occasionally, on subsequent 1990s tours, one would pop its head, but it wasn’t until the E Street Band Reunion tour in 1999, that Bruce opened his songbook and made a place for nearly all of them. Whenever Bruce and the band busted into one of those classic intros, it was like witnessing Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis reunite on the 1976 MDA Telethon.

It’s really not fair to hold an artist to their earliest work, even though it’s often their most beloved, but Bruce is a little different. The first 20 years of his career are filled with so many stylistic changes, shifts and looks that he almost seems like three or four different artists in one guy. Bruce still enjoys reliving that portion of his career on stage, but, with archival releases, the first two albums seem to get short shrift. When he released his big live box set for the Christmas season of 1986, his oldest performance dated back to 1975. In 2014, Bruce began releasing entire live shows available for download on his website and, over a 10-year period, has released hundreds of complete live performances but nothing from 1972 to 1974. His albums “Born to Run,” “Darkness on the Edge of Town” and “The River” have all been rereleased as deluxe edition box sets, but his first two albums were not, even though both contain plenty of unreleased material. But Bruce’s archives are mammoth, and he may surprise us all one day. I think back often to that conversation on the New Jersey Transit platform and how some unknown lady accidentally urged me to take a deeper dive and enjoy the fullness of Bruce Springsteen’s musical journey. I haven’t looked back.

Wow, excellent article! This album is my “desert island disc”! It was the first Bruce album I heard in January of 1975 when visiting my older brother in Boston. I was a freshman in college and into Dylan and Van Morrison’s “ Moondance”. My first show was six months later in Providence (Steve’s “first” show) , followed by waiting outside the Bottom Line for 8 hours for the early Thursday show (once the show started they let in about 50 or so people and were were just a few feet from the stage). It was well worth the $5 ticket! seen about 40-45 shows over the years, mostly last century, including Bridge Concert 1, both Christic Shows, mtv unplugged, and the special treat of the Roy Orbison show. I’ve been to two tour-closers ( Boston 77, LA 85) and am excited to say I’m going to Vancouver tomorrow 11/22 for the show! (I grew up in Connecticut, moved to So Cal in 1978, and up to Washington State after retiring a couple of years ago.)

Thank you for the article, I learned some new things and now know for sure why this is his best/my favorite album!