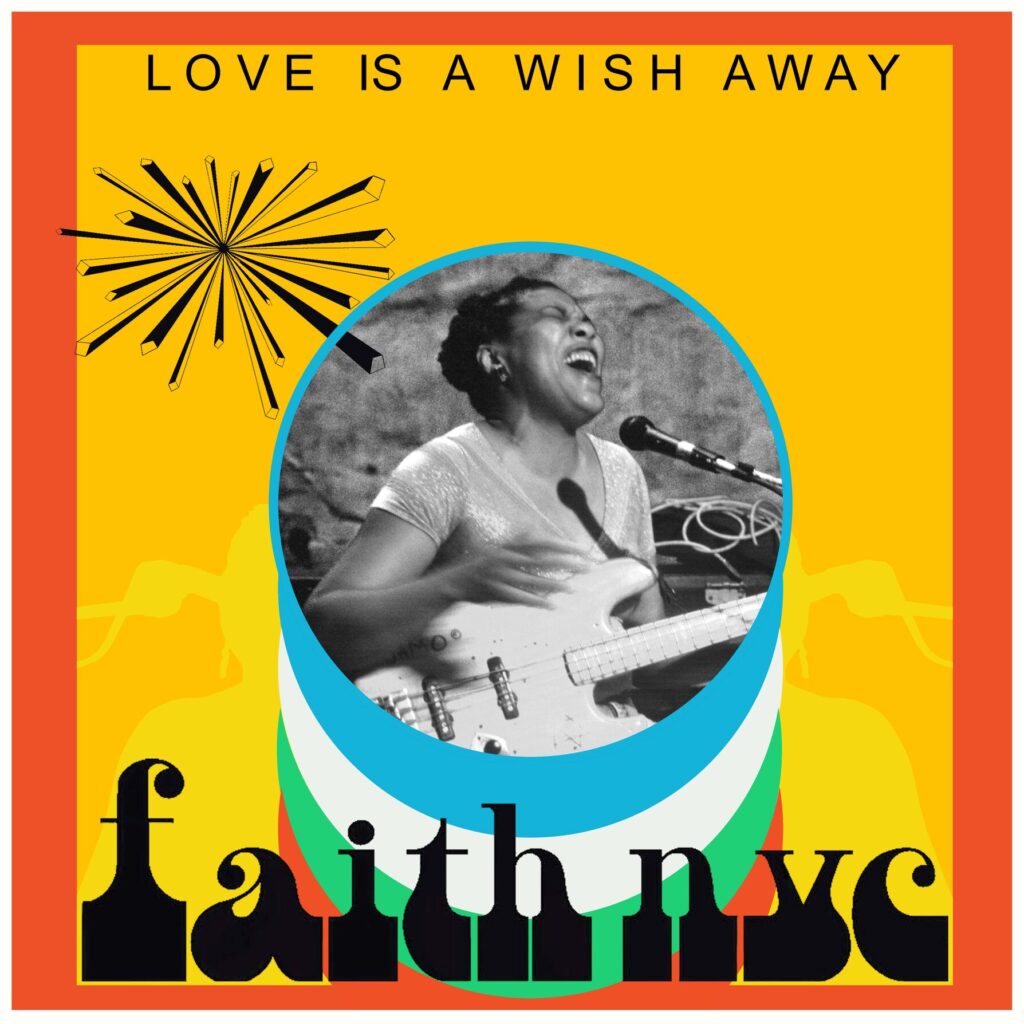

Felice Rosser (Credit: David Corio)

Felice Rosser, the creative force behind FaithNYC, has been shaping New York’s music scene with her distinctive blend of punk, reggae, funk, and African influences. With her new album, Love Is A Wish Away, Rosser explores themes of resilience and connection, drawing from a lifetime of diverse musical experiences. Produced by Justin Adams, known for his work with Robert Plant, the album showcases her dedication to breaking musical boundaries. In this interview with Jason Barnard, Rosser shares insights on her creative evolution and the inspiration behind her latest material.

Love Is A Wish Away, has been described as a fusion of multiple genres. How do you approach blending such a wide range of influences while still keeping your sound cohesive?

I’ve always found this genre thing very kind of artificial. I have always been touched by many kinds of music. I’m a fan! when I lived in Paris and in the 1980s, I lived in a North African neighborhood, and I fell in love with the music playing on the jukeboxes in cafes there. I fell in love with Ait Mengulait and Idir and Gnawa music. Living here in New York of course I loved punk that but then I’m not going to just stay in punk. I got into reggae got into Brooklyn got into playing the bass and learned so much about the music and the culture Jamaican culture, Rastafarian culture so of course I’m going to express it in my music because that’s my life. When I lived in the East Village in the 1980s there were many jazz musicians and free jazz musicians around so that freedom, that exploration is going to be part of my thing.

I love Blues and so if you’re loving the Blues, you keep following it back and you start getting into Wassoulou music and music from Mali and the female singers Coumba Sidibe, Nahawa Doumbia and people like that. That’s the music I love of course it’s going to be reflected in what I’m doing. I’m the bass player on all the songs, so there would be a common sensibility there. Just filtered through different vibes. Many of the musicians I admire have a wide range of influences, The Clash on Sandinista for example. Earth Wind and Fire used African and Brazilian instruments on their early 70’s records.

Having grown up in Detroit and experienced key moments like the 1967 riots and Motown’s golden age, how did those early experiences shape your approach to music and storytelling?

They certainly set a high bar of musical excellence to reach for. Motown made such great records, The MC5 and The Stooges, Aretha Franklin made such great records and one of my goals in music is to just try to incorporate some of that the feeling maybe not the chord changes maybe not all the intricate orchestration but some of that feeling some of that determination then some of that beauty into my work. Growing up in in Detroit and when I did seed this desire I have to make great records.

You’ve had a fascinating journey from playing with Brooklyn’s all-female reggae band Sistren to forming FaithNYC and becoming a part of Vernon Reid’s Black Rock Coalition. How has your perspective on the music industry evolved since those early days?

I’m just always trying to become a better bassist and singer, and trying to write good songs. I want to learn and grow. I’ve always been the bass player in the band, or the bass player and singer in the band, or the songwriter, bass player, singer in the band, or the singer in the band, and gone from clubs to larger venues, and back to clubs and record company offices, and all those sorts of things. But I’ve just always been there with my bass on my back and my songs, trying to keep my voice in pitch.

Whatever the industry is doing around me, I don’t really know. I mean, I certainly can hear the changes in the beats and grooves and sounds, and certainly in the way music gets to the people these days, but I’ve always been essentially the same person doing the same thing, maybe with different accompaniment, but the same sensibility has always been there. And I’m always trying to get closer to that sensibility, to that heart and mind without the judgmental voices, but to the true essence of what my soul wants to express. Just trying to get a little closer to that through calming down, through meditation, through yoga, through being in nature, through dancing, through having fun. Trying to listen, to hear what wants to be expressed, get a little closer to that—that’s my goal. I’ve never made a lot of money playing music. Maybe that’ll change.

I started out in punk. I started out at CBGB’s and Tier 3, doing benefits in Tompkins Square Park, squat benefits and Rock Against Racism benefits in Union Square. I never thought about the mainstream. I never thought any music industry people were going to be interested in what I was doing because there’s nothing about me that’s mainstream at all. I have always wanted to do what I wanted to do and play what I wanted to play. I’ve had people say I should be more hip hop or you should be more R&B or whatever but you know I’m from Detroit and I always want to rock I’ll always have that in me. Now the fact that people are saying our record is great or it’s so interesting is very gratifying. I’m happy that some people “get it”. It means that they understand this amalgamation of sounds and influences.

Justin Adams, who produced Love Is A Wish Away, has worked with artists like Robert Plant and Tinariwen. How did this collaboration come about, and what unique contributions did he bring to the album?

Justin and I have a mutual friend, Malu Halasa. Malu took me to see Robert Plant when Justin was in his band. I followed Justin’s recording over the years and saw that he collaborated with many artists I admire, including Tinariwen and Juldeh Camara and Gnawa musicians. My husband and I had gone to Paris, and we were looking for some good music venues Malu suggested I write Justin and ask him, as he frequently plays there. I happened just by chance to include a demo of the song Zion in my email, which he liked. Malu heard “Zion” and liked it as well. She then proposed that we work together, and Justin suggested a small studio near Bath. And Justin is basically an old school punk rocker like me who shares a love for reggae, a love for African music and a love for Stax, Motown and funk. He was an integral part of making the record because he can incorporate all my influences and doesn’t think it’s weird.

For instance for the song “I Stood Up” I always thought it should have an African, Diblo Dibala type of feel , or “Can I Make It Up to You” I’ve always wanted it to have a little Eddie Floyd Stax kind of thing in there and Justin knows who all these people are he’s able to filter his own sensibility through a lot of the things that I love , so he his influence was enormous. Also, he had a vision to bring out in the songs. On the demo “Eagle Street” is just a little song, and he made it sound so beautiful he added so so much depth and drama to the song. I was very happy. He brought a lot a lot to the music

Punk has been a liberating force for some women. Can you share more about your experiences on the New York punk scene, and how punk allowed you to break traditional norms of the music industry?

Well as a black female coming up, if you’re a singer, there are so many the great girls who have started out at age 4 singing in church. If you that’s not your background, punk allowed people like me who didn’t have a church background to give music a try. I was a writer and a photographer when I came to college in New York and at CBGB I met my friend deerfrance who worked there and said “let’s form a band, we don’t need 2 guitars you play bass” because I played a little folk guitar from back in the day. But she said play bass and I was like OK sure, and we saw Tina Weymouth from the Talking Heads playing the bass, the stage at CBGB’s wasn’t so high. The stage at Cobo Hall, the arena in Detroit where I saw many shows the stage is like 100 feet high but the stage at CBGB’s was like 2 feet high and I felt like maybe I could get up there and especially seeing Tina. Then we heard The Slits, and I saw Tessa from The Slits playing bass too, so I thought yeah bass is a cool instrument and also because I love reggae. I thought I would give it a try and that was all because of punk you know everyone was just giving things. I really liked playing it. I found I really enjoyed it. I didn’t have to be a virtuoso; I could just play my own thing, and it would still have value. I feel like punk liberated me.

The track ‘Can I Make It Up to You?’ explores personal themes such as guilt and regret. How do you channel such personal emotions into your songwriting, and how does the process of performing these songs impact you emotionally?

Every time I sing it I’m still asking the question, Can I make it up to you? It doesn’t make me sad to sing it. It connects me to my grandmother and that time in in my life. I remember the time of that song, being in Paris and seeing the Cathedral of Notre Dame with it’s dark walls and flickering candles. Walking along the Seine wondering how my grandmother was doing. I didn’t have a telephone where I lived so I would call home once a week. That song preserves her memory, and I feel her presence when I sing it. I’m grateful for that song.

There’s a sense of New York and Detroit’s cultural history in your music. How do these cities continue to inspire your music and creative process?

Detroit has always been very honest about music. We grew up with the MC5 and the feeling that music means something. You can change the world around you with music. Growing up in Detroit when I did, means it’s not strange at all to love blues and rock and jazz and funk and poetry and mix them all together. I look to Detroit for many of the great records and musicianship and honesty that I love and try to keep going.

I think New York gave me a push towards experimental things. And a funky street groove. One of my desires is to hear one of our songs blasting from a car sound system on the Lower East Side.

Thank you for asking such cool questions and giving me a chance.