Bill Bruford reflects on his evolution from the drummer for Yes and King Crimson to a leader in jazz fusion. Known for his constant innovation and the pioneering use of electronic drums, Bruford’s thoughts reveal a deep commitment to exploration and the pursuit of musical collaboration. Now back after a lengthy break from performing, Bruford offers a look at his creative processes, the role of technology in shaping his sound, and his return to live performance with the Pete Roth Trio.

The Best of Bill Bruford – The Winterfold & Summerfold Years is being released. Your early solo albums, such as Feels Good to Me and One of a Kind showcase not just your drumming but also your compositional voice. Can you speak about how your approach to writing evolved during this period and the balance you aimed to strike between structure and improvisation?

I committed all the beginner’s mistakes of course: which principally involved writing too much and then moving on to a new idea before the last one had been properly examined and played out. The art in jazz is to be able to write a couple of tone rows or modes on the back of an envelope. But knowing what the right scales and modes are that are going to give you, for example, Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue, takes some figuring out, especially if you’re new to it as a drummer-leader. I believe in writing partnerships. All my partners – Dave Stewart, Django Bates, Tim Garland, Steve Hamilton and others – knew more than I did and were very generous with their knowledge.

Your work with musicians like Allan Holdsworth, Annette Peacock, and Dave Stewart introduced a variety of textures and sounds. How did these collaborations shape the direction of your projects, and how important was the interplay between different instruments in developing your overall sound?

Logistically, the arrival of the Prophet 5 synthesizer enabled ‘Bruford’ to exist! We no longer had to carry Dave’s Hammond organ around! Very expensive, especially on foreign tours. All the technological leaps, from Hammond (early Yes) to Mellotrons (early King Crimson) to synths in my band, shaped the sound and direction of the groups profoundly. Musicians love to play with new gizmos.

The improvement in electronic drums, over years, enabled the ideas to take root and flourish, but it was hard work. King Crimson’s ‘Discipline’ album wouldn’t have happened without Roland guitar synthesis: and so it goes on. Musicians spend an inordinate amount of time searching for the ‘perfect sound’, understood as the one in their head that won’t let them get to sleep at night until they realize it. In the 1970s, Holdsworth could be found on stage soldering amplifiers together five minutes before they let the audience in.

The shift from your electrified, rock-driven music on Winterfold to the more acoustic, improvisational work on Summerfold marked a transition. What inspired this shift, and how did working with Earthworks help you explore new sonic territories?

I’ve been shifting my whole career, trying to find something interesting to do on the drums. I’m more interested in what drums can do today, and might do tomorrow, than any great love for progressive rock, or, in fact, popular music in general. The music genre is just the space I inhabit in order to play what I want to play. In 1980s King Crimson, that genre was called ‘rock’, then heard as an exciting place to be, much more so than an utterly predictable, soft instrumental music called smooth jazz. In the 1980s I was proud to be a rock musician. Now, interactive music – what used to be called jazz in the 20th century – is the only place to be. Stadium rock tours (do they still have them?) are death. Intimate, interactive music is life. I’ve tried both. I’ve given up trying to fit in. Now I just make Bill size decisions on Bill-type music. Earthworks was my sandpit for 20 years. The participants encouraged my writing and my Bill-ness, bless them.

How did advances in drum technology influence your creative process, especially in pieces like “Up North” and “Stromboli Kicks”?

There was much promise at the beginning of the electronic drum revolution in the 1980s, but the instruments were poorly made, and the marketing absurd, suggesting we’d all be throwing away our acoustic instruments in a years or two. I formed a band called Earthworks around the notion that the drummer, through Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI), would provide the rhythmic and chordal information while the single note front line players on saxophone and tenor horn would play melodies and improvisations. The two songs you mention, ‘Up North’ and ‘Stromboli Kicks’ were good examples of that. The technology improved enormously over the ensuing years, to the point where I could play an interesting confection of percussion samples, chords and melodic line, or sound like a pitched thumb-piano throughout (‘Thistledown’, from If Summer Had its Ghosts)

Your 1997 collaboration with Ralph Towner and Eddie Gomez on If Summer Had Its Ghosts has been described as a career watershed. What drew you to such a lyrical, all-acoustic approach at this stage, and how did you see it as a contrast to the heavier, more experimental work with King Crimson and Earthworks?

It was a reaction I think to the muscular, hyper-driven jazz fusion of the day which I felt was irrelevant after about 1980. I was after something altogether more poetic – softer, hazy, autumnal. Pete Erskine and Paul Motian are a couple of the very few drummers who could caress you rather than beat you up, and there was an intimacy in the quality of their recent work that I wanted to follow up on with Ralph Towner and Eddie Gomez. Two or three acoustic instruments can fill a huge sonic space on disc, as if the whole aural spectrum is available to them. I wanted everything played quietly and mixed loud, playing on that falsity of foreground that recording can give you. With titles like ‘Somersaults’ and ‘Thistledown’, I wanted the music to have a dreamy, ‘secret garden’ feel. Generally, I think the project worked.

Yes, it was very much in contrast to the neurosis surrounding King Crimson’s oeuvre, and the jazz-quirkiness of early Earthworks, but just put that down to a young man trying to find his way in the world and his place in music. That’s why I’m a musician, to help me with that stuff.

The box set includes live recordings, such as “Footloose and Fancy Free” with Earthworks Underground Orchestra. You’ve mentioned that jazz is often better experienced live than in the studio. What do you think it is about the live environment that brings out the best in your playing, and how does it affect your approach to improvisation?

In live improvised performance, you live on the edge, in the moment. Arms and legs are moving, trained after years of practice to perform what you’re imagining. Ideally there’s is no time delay between the intention and the appropriate audible result. There can be some forward planning, “I want the music to halve in dynamics when the saxophonist has concluded this phrase”, but generally, by the time you’ve thought and planned, the moment has gone. Time collapses.

I remember vividly a duo concert in London’s Purcell Room on London’s South Bank, with Dutch improvising maestro Michiel Borstlap on piano and keyboards. It was being recorded by the BBC. We had decided to do it without any prepared music whatsoever. Madness. It was exhausting and exhilarating at the same time. 75 minutes felt like 30. In rock, almost everything is pre-planned, including the ‘guitar solos’, so of limited interest. So little is allowed to happen. In improvised music, some might say, too much is allowed to happen. I’d rather err on the side of the latter than the former.

Throughout your career, you’ve constantly balanced the technical side of drumming with a desire to push creative boundaries. With your work in the World Drummers Ensemble, you explored percussion in a global context. How did that experience refine your understanding of rhythm and melody in a cross-cultural setting?

It refines your sense of melody. In the west we are accustomed to playing with instruments of definite pitch. Drums are said to be semi-definitely, or indefinitely pitched. That is, you can tell a higher drum from a lower one, and a lower one still, but generally the pitch is indefinite. In a percussion ensemble, the focus is on rhythm, naturally, but also on timbre, or the sound of the drums. What will it sound like when you put two western kit drummers (Bruford and Wackerman) with a Grammy-winning Afro Cuban master (Luis Conte) and a cultural ambassador for Sengal playing his 100-year old Sabar (Doudou N’Diaye Rose)? The best musicians are always asking: “What will it sound like if…?”

In many other cultures, drums and percussion are accorded primacy. The invention of tonal harmony in the west downgraded the rhythmic aspect of the music, which remained very much at the forefront of those countries that didn’t marry into tonal harmony for whatever reason – China, African nations, the Indian subcontinent, Java, Bali and so on.

With the inclusion of pieces like “Beelzebub” from Feels Good to Me, how do you approach revisiting and reinterpreting your earlier compositions, and what do you discover in them when you return to them years later?

A contemporary acoustic version of Beelzebub was included because it was the first thing, with the exception of some prog rock bits and pieces, that I wrote for a band under my name. The original was a powerful Holdsworth / Berlin / Stewart electric version recorded decades before the Garland / Hamiton / Hodgson acoustic remake in 2002. We discovered a) how comparatively easy it was to play now (it was considered ‘difficult’ in 1977); and b) how we could squeeze better dynamic variation out of it with acoustic instruments. A comparison of the two versions is worthwhile.

Drumming is deeply physical, and you’ve spoken about the technical precision required. Do you ever think about the connection between your physical movements as a drummer and the emotional or psychological impact they have on the music and audience? How do you view the physicality of your art?

Do I never stop thinking about those things! Performing on any instrument of course is deeply physical. Try standing with a violin under your chin for ten minutes, let alone a three hour concert. In that respect, drums are no different. An organist is the only other musician who uses all four limbs. Varying the dynamic and timbral components of a complete four-limb rhythm, which is itself in perpetual change, is exhilarating and tricky. An audience is paying, among other things, to see and hear this done with complete and effortless command and control by the instrumentalist.

For myself, I’m aiming for elegance, economy, and effortlessness in my own playing. When I get glimpses of that, I’m a happy boy, but I cannot judge the emotional or psychological impact on the audience. Judging by the smiling faces though, I’m pretty sure they like it.

The box set booklet references a quote from Henry Miller about leaving a significant mark on the world. Do you feel that your extensive body of work has fulfilled that vision, and how do you view the ‘scar’ you’ve left on the face of music?

Well, I think the scar we greedy human animals all leave is on the face of the world, rather than music. I continue to try to make good in my world through the healing force of music. I feel I’ve made a mark: whether it has significance or not is for others to say.

Are you working on any new projects currently, or have anything new in the pipeline?

I’ve only just returned to music after complete burnout in 2009. For 13 years, I couldn’t stand the sight of a drumkit. Finding my way back after a long time in academia, was explosive, unexpected, and very sudden. I remember passing someone else’s kit one day, sitting down, and feeling exhilarated all over: urgently and violently keen to start all over again. I’d sold all my own drums, years earlier, so I had to go and find a new set and start a daily two-hour daily practice routine.

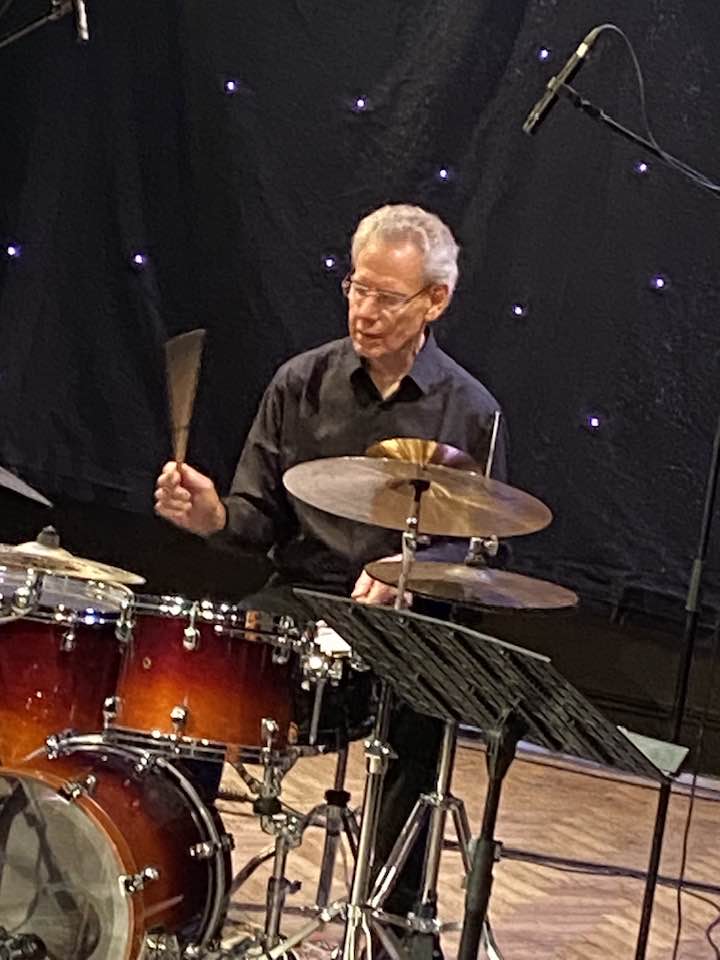

In 2022 I formed a rehearsal band with Guildford guitarist Pete Roth. Pete had worked as my drum tech in Earthworks 20 years previously. I knew he was an accomplished guitarist, but I was astonished how far he’s come by the time we started working on the highly interactive, jazz-adjacent music and writing that we do today. One thing led to another through 2023; a few local gigs came along, but only in South-East England. Then a festival or two, and now the Pete Roth Trio has a dozen dates this autumn in theatres and arts centres, with festivals and clubs to come through 2025. It’s a privilege to support and mentor a much younger player, and I get to play whatever I want on the tubs. We prefer smaller places where we can see the whites of your eyes, hear your breathing in the quiet bits and have a musical relationship with you, of the sort that not possible in the big places. Believe me, I’ve tried ‘em both. Great to be back!

Further information

Pete Roth Trio tour: Dates and Tickets

The Best of Bill Bruford – The Winterfold & Summerfold Years

So glad to see you’re back!

So glad your back music from retirement.

The music has been getting somewhat constant four four I can’t wait to hear some new Bill Bruford Beats

Thank You for coming back!!!!

Bill.. simply the best!!

Saw them play on Nov. 1, 2024. What a thrill. In jazz-sized rooms, you can really see the musical interaction. Pete Roth Trio takes things back toward a bit of an electric sound for Bill, even though he’s on all acoustic drums. There were 3-4 brand new tunes, and they were excellent. Tempos were quick, and there was even a trace of funk in there at times. It’s not quite like any of his previous jazz work, and their interpretations of a few classics (Coltrane, Shorter, Charlie Parker, Gershwin, even Dvorak) all scored with the audience. This is a most welcome return. All three players are excellent, and it’s very much worth hearing and seeing.

BB’s been a huge influence on my drumming since we met via records in the early 70’s. It’s a thrill to learn he’s back on the throne. Almost worth a trip to Europe to see the new group. Bravo.

I’m so glad you’re back, Bill!

YAY BILL!

Now, Bill, have some F-U-N!

“Well, I think the scar we greedy human animals all leave is on the face of the world, rather than music. I continue to try to make good in my world through the healing force of music.”

Whoo! For a second there I spaced out and thought I was reading a Jon Anderson interview… Well said Bill.

A friend and I saw one of Bill’s last shows in the states thirteen years ago. Glad he’s back playing. PRT’s management should “ring” all the universities Bill once played in the Midwest and line up some gigs in quiet venues, and make it easy for students to get a listen.